When camping was no picnic

Alan Collier's letters describe harsh experiences in three of B.C.'s 235 "relief" camps during the Depression.

May 14th, 2018

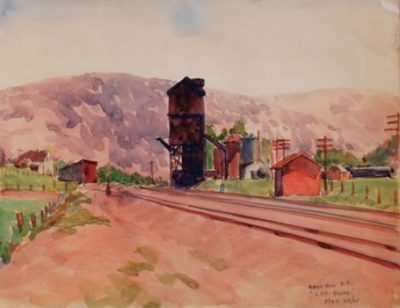

Alan Collier's painting of Big Bend Highway, North of Revelstoke. (Roberts Gallery, Toronto)

In the ’30s and ’40s, he became a leftist in response to the intransigence of the authorities; he later became a full-time artist.

Alan Caswell Collier, Relief Stiff: An Artist’s Letters from Depression-era British Columbia

by Peter Neary (editor)

Vancouver: UBC Press, 2018.

$45 / 9780774834988

Reviewed by Daniel Francis

“You have to protest once in a while for the good of your health.” — Alan Collier

*

Most British Columbians live within an easy drive of one of the unemployment relief camps established by the federal government during the Great Depression. But since they are overgrown or repurposed, most of us are unaware that these sites exist.

Most British Columbians live within an easy drive of one of the unemployment relief camps established by the federal government during the Great Depression. But since they are overgrown or repurposed, most of us are unaware that these sites exist.

A few minutes from my own home, for instance, on a busy parkway in North Vancouver, is a large piece of vacant bushland. Commuters drive by it every day without a second glance and, until a commemorative plaque went up recently, they would have no reason to know that during the Thirties it was the site of one of the camps in the Lower Mainland where young, jobless men were set to work building a rifle range for the military.

The camps were an attempt to deal with the challenge of unemployment and the social unrest the government feared would result. Tens of thousands of single men were travelling across the country looking for work and when work was not available, looking for relief. A large number congregated in Vancouver, which became known as “the Mecca of the Unemployed.” But the city was overburdened and could do very little for the men.

Neighbouring communities such as Burnaby and North Vancouver actually went bankrupt, turning their governments over to specially appointed commissioners. The situation in Vancouver was not that dire, but the city’s ravines and parks were filled with homeless men and its streets seethed with protestors demanding that something be done to ease the suffering.

In September of 1931 the province established the first camps — about 235 of them — where single men got “jobs” building roads, bridges, airstrips and other public amenities. Anything to get them off the streets and away from the persuasive rhetoric of radical agitators.

The following year the federal government launched its own program of camps, administered by the Department of National Defence, and soon took control of the provincial facilities as well.

Men who entered the camps were known as “relief stiffs,” or “Royal Twenty Centers” for the 20 cents per day they received in pay, along with food, lodging and clothing.

“Essentially they were warehouses for the young,” writes historian Peter Neary in the introduction to his new book. The experience was somewhere between a prison and a military barracks. The men were free to leave, Neary notes, but the alternative was almost sure unemployment and “the perils of hobo existence.”

Neary’s book is a first-person account of day-to-day life in the B.C. camps. It collects a series of letters written by Alan Collier (1911-90), a Toronto-born artist, while he lived in three separate camps in the Interior between September 1934 and May 1935. Like so many of his fellow “stiffs,” Collier, who was a graduate of the Ontario College of Art, came west on the promise of a job and then when he got here found no job available. He was happy enough to enter a camp, treating it as something of an adventure that would see him through the winter until he could return to his fiancée, Ruth Brown, in Toronto.

When Collier arrived at his first camp, located on the Big Bend Highway north of Revelstoke, he recognized right away how pointless the work was. The Big Bend was the final link in the highway system between Alberta and the coast, following the 305-kilometre “big bend” of the Columbia River as it looped from Golden to Revelstoke. Construction had begun in 1929 and the road would not open until 1940. The work was tedious and hard and in Collier’s view “a huge waste of money” since a decent highway was never going to be built through such difficult terrain. (He was correct; the completed road was impassable during the winter and shunned by motorists and truckers the rest of the time.)

Collier was, in the words of Neary, “a born contrarian.” He was not a radical but he had his self-respect and he didn’t like the military discipline that ruled the camps. Before long he was leading some of the other men in a protest against their treatment. “You can never speak a word against authority in these camps without being considered a Communist,” he complained to Ruth. But in his view, “you have to protest once in a while for the good of your health.”

A couple of factors made life in the camps easier for Collier than for the average “stiff.” First of all, he was an artist who used his spare time to sketch and paint portraits of some of the other men. In other words, he did not suffer from the monotony that afflicted camp life. Secondly, after a brief period as a labourer he managed to get himself an administrative job so he was spared the hard, pick and shovel labour of winter road construction. “At first I bemoaned by fate,” he wrote, but once he moved into the office, “I have no regrets and have enjoyed this past month very much.”

The generally accepted narrative of the camps is that they were inhumane dumping grounds for the unemployed, incubators of unrest and radicalization. Neary’s book does not contradict this view, but it does provide something of a counter-narrative. Collier’s letters reveal someone who kicked against the restrictions and petty stupidities of camp life but at the same time had little sympathy for the radicals who agitated to remediate them. In his view the Communists who were organizing the workers to strike were lazy malingerers whose unrealistic demands would only make things worse in the camps.

“Personally,” he wrote his fiancée, “I think the stiffs are pretty well treated and are lucky to get what they are getting.” Needless to say this minority attitude did not make him popular with the other men and one gets the impression of someone who was a bit arrogant, a bit aloof, who saw himself, because of his education and middle-class background, to be a cut above the average “stiff.” At the same time Collier agreed with many of the grievances expressed by the Communists, including their demand that the daily stipend be raised. At times his differences with the radical firebrands seem to have been personal; he just did not like or respect them.

Collier’s letters provide a description of events leading up to the general strike of April 3, 1935. At the urging of organizers, men left the camps en masse and descended on Vancouver where they held regular street protests. The intransigence of the authorities culminated on April 23 when Mayor Gerry McGeer responded to a massive demonstration by reading the Riot Act in Victory Square. While demonstrators remained defiant, they recognized that local government would do little for them and they decided to carry their protest to Ottawa by rail, initiating the famous On-To-Ottawa Trek.

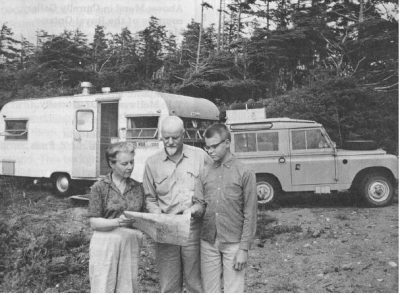

Alan Collier has nothing to say about these events. After about half the men in his camp left for Vancouver, he remained behind to take care of various administrative duties and then travelled down to the coast himself, not to take part in the protest but to begin his journey back to Ontario. Neary’s afterword summarizes Collier’s subsequent career as a miner, sheet metal worker, World War Two soldier, husband and eventually a fulltime artist. As the years passed his politics veered to the left and Collier ended up endorsing many of the ideas that he had rejected in the camps. Not to say that he ever became a Communist, but he did become a strong supporter of the CCF, later the NDP, and was active in union activities.

Collier married Ruth Brown in 1941 and together they made a comfortable life in what Neary describes as “the broad, sunlit economic uplands of the 1950s.” By this time the rigours of the Depression-era work camps must have seemed a distant memory.

Peter Neary has done a real service by bringing Alan Collier’s letters to a wide public audience. Collier’s views of the politics of the camps, while contentious, provide a useful comparison to the more familiar leftist reading of the era. More importantly, his letters, along with the paintings and photographs that Neary has collected, provide an intimate and detailed glimpse, a view from the inside, of the relief camp system, a short-lived but embryonic experiment in social control during a time of economic crisis.

*

November 22, 2017. Her Excellency Julie Payette presents The Governor General’s History Award for Popular Media (Pierre Berton Award) to Daniel Francis.

Historian Daniel Francis, arguably the province’s hardest-working and prolific popular historian, edited the most essential book about the province, the Encyclopedia of British Columbia (Harbour, 2000), having previously worked as an editor for Mel Hurtig’s Encyclopedia of Canada. Francis has also written the definitive biography of Louis Denison Taylor, which received the City of Vancouver Book Award in 2004. He recently received the Governor General’s History Award for Popular Media / The Pierre Berton Award at Rideau Hall in Ottawa. For more information about Francis and his thirty books, see his entry on ABCBookWorld.

*

The Ormsby Review. More Books. More Reviews. More Often.

Reviews Editor: Richard Mackie

Reviews Publisher: Alan Twigg

The Ormsby Review is a journal service for serious coverage of B.C. books and authors, hosted by Simon Fraser University. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Robin Fisher, Cole Harris, Wade Davis, Hugh Johnston, Patricia Roy, David Stouck, and Graeme Wynn. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk.

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

Leave a Reply