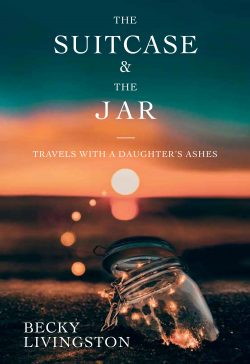

The suitcase and the jar

As a grieving mother, Becky Livingstone set off on a global walkabout for 798 days, scattering her daughter Rachel’s ashes a bit at a time.

September 13th, 2018

Becky Livingston lost her 23-year-old daughter Rachel to a brain tumour.

Reviewer Carys Cragg calls Livingston’s journey, told in The Suitcase and the Jar, “masterfully overwhelming and at once heartbreaking and stunningly beautiful.”

The Suitcase and the Jar: Travels with a Daughter’s Ashes

by Becky Livingston

Halfmoon Bay: Caitlin Press, 2018

$22.95 / 9781987915747

Reviewed by Carys Cragg

*

Previously of North Vancouver, English-born Becky Livingston now lives in Nelson. She says, “This book is for grievers and travellers, mothers and daughters, lovers and wanderers, and for anyone who has ever considered that, “You think you know the shape of your life but one day the whole fucking thing falls apart.” — Ed.

*

Eighteen months after her daughter’s death, untethered to the life she has left behind, Becky Livingston set forth on a journey to continue her daughter Rachel’s dying wishes to keep travelling and to honour her own compelling need to uproot a once-familiar sense of belonging. The Suitcase and the Jar: Travels with a Daughter’s Ashes takes us across the globe and the terrain of loss as we are invited into a contemplative state of being. We are asked to consider: Who am I without someone who is essential to my being? Where is home when what I have come to know I no longer recognize?

Eighteen months after her daughter’s death, untethered to the life she has left behind, Becky Livingston set forth on a journey to continue her daughter Rachel’s dying wishes to keep travelling and to honour her own compelling need to uproot a once-familiar sense of belonging. The Suitcase and the Jar: Travels with a Daughter’s Ashes takes us across the globe and the terrain of loss as we are invited into a contemplative state of being. We are asked to consider: Who am I without someone who is essential to my being? Where is home when what I have come to know I no longer recognize?

Leaving her house and job, Livingston takes us from one temporary home to the next, carrying and scattering Rachel’s ashes wherever she goes on a journey of 798 days, housesitting for one to seven weeks at a time. We find ourselves “crossing borders, skipping seasons, changing hemispheres” (p. 5). She travels from her family home in North Vancouver to Mallorca, Spain; to County Clare, Ireland; to Zurich, Switzerland; to Northumberland and Leicestershire in England; to Bunbury, Melbourne, and Launceston in Australia; to Delhi, India; to New York, Seattle, San Francisco, and finally back to British Columbia.

Interspersed throughout her travels, we move back in time, bearing witness through a mother’s eyes to the all-consuming destruction of cancer of her daughter’s body and mind at the age of 23. We witness Livingston as she experiences not one but two deaths that shatter her world, the kind of grief that “changes the narrative of your life” (p. 133), and as she embarks on a journey that is “a way of stepping forward, about doing what you think will help ease the grief, about not knowing and then doing something anyway” (p. 131).

While Livingston foregrounds her daughter’s illness, she also recounts her fiancé’s death of a similar fate. Meanwhile, she populates her story with the other people central to her life: her ex-husband, who moves back into the home where their daughter is dying; her younger daughter, who later moved away; and the friends and travellers along the way. As with any great quest, there are the requisite naysayers, doubters, and judgers, telling her she “won’t find what [she’s] looking for in some far-off land” (p. 17). Alongside the description of Rachel dying we also learn how she lived in her short life: as a world-traveller, always planning her next trip, and how “easy she was to love” (p. 99).

At its core, The Suitcase and the Jar is a contemplation on grieving itself, buoyed by the harrowing details of illness and death. Readers may be reminded of Joan Didion’s nonlinear, intensely introspective rumination on mothering and her daughter’s death in Blue Nights (2011), or perhaps Cheryl Strayed’s self-imposed hiking exile from her known life to process her mother’s death in Wild: From Lost to Found on the Pacific Crest Trail (2012).

Scattered throughout the pages of The Suitcase and the Jar are fragments of Livingston’s grief as it morphs and evolves with each passing housesitting destination and every location at which she leaves a portion of Rachel’s ashes. Livingston grapples with how she managed her daughter’s needs. “We snuggle them up, we talk baby-talk, hoping as we do to absorb some of their pain” (p. 104). She shows us the intimate and painful realities of a parent who has lost her child: “Nobody messes with a grieving mother” (p. 147). “No one knows what to do with a person like me” (p. 166). And she reflects on the purpose of her journey: “I wanted her to know above everything else that my journey was a result of her love” (p. 13). These moments are brutally real, exquisitely painful, and authentic in a way that anyone who has lost someone close will immediately recognize.

Helping deepen the narrative, Livingston frequently refers to the music playing within particular memories and to books she has read that resonated in some way. She even at times quotes from poems (for example, “Grief” by Stephen Dobyns, “Lost” by David Wagoner, and “For the Traveller” by John O’Donohue). Both song and book references might have benefitted from an excerpted line or phrase (or a paraphrased comment where copyright restrictions prohibited her from quoting directly) to help the reader to understand their importance further. Otherwise, the approximately thirty references risk becoming distracting, or worse, the reader might fail to fully comprehend the connection. A list of “Books, Songs, and Poems,” in the back pages or available online, would be an added resource for the reader, as so often we seek music and literature to show us a path through our grief.

Livingston manages movement well. It emerges as a significant theme. Back and forth between past and present, her transitions are seamless. In one sentence, she describes how her daughter liked to fly, and in the following paragraph, Livingston is waiting to board a plane. So too does she mark space and time well, whether in a description of a hike she’s taking on an island we found ourselves in a few chapters ago, or as narratives attached to specific markers of time – 2005, 2011, 2002, 2010, 2004 — and back again. The constant movement from one continent to the next risks disorienting the reader, but Livingston anchors us with a repeating action: the scattering of her daughter’s ashes in yet-to-be-determined locations. Where will she choose to leave them? How will she decide? How will it feel?

As Livingston lets go of her ashes, she lets go of her daughter, giving her to the world to carry forward. Prepare for emotion to overwhelm. She likes to think that Rachel is “playing in the shifting sands, caught between your children’s toes or carried home in a castle-shaped pail. All of us carrying her away” (p. 15).

At times The Suitcase and the Jar reads as poetry, with keen attention to the sound and aesthetics of the page, for example “You. / Open. / Touch. / Feel. / Her. / Let her go.” (p. 9). Livingston pays attention to how sentences make the tongue and the emotions move: “Her ashes like asteroids pit the bleached sand” (p. 134). The crescendo of locations that Livingston lists where she has scattered Rachel’s ashes — place by place by place by place (p. 163) — is masterfully overwhelming and at once heartbreaking and stunningly beautiful. She deftly uses chapter length to move the reader from travelling and back into the painful moments of Rachel’s death; this is done with 22 relatively short chapters that contrast with one lengthy one (Chapter 7, “Limps to Stumbles”).

Despite the length of Chapter 7, Livingston skims over some interactions that arguably could have been extended. For example, “She talked about her day. It was a struggle to follow. Still, I hung on to every word” (pp. 51-52). What exact words, syntax, and hesitations does Rachel use to attempt to describe her day, while in the midst of losing her ability to communicate? She frequently uses fragmented sentences — “My despair fully exposed… Just one more step … Keep going … Risk life for just one more day” (pp. 28-30) — which mirror the fragile, contemplative nature of grief itself.

This book is for grievers and travellers, mothers and daughters, lovers and wanderers, and for anyone who has ever considered that, “You think you know the shape of your life but one day the whole fucking thing falls apart” (p. 26). Livingston gives us such a nuanced and detailed picture of her journey that we can attach some piece of ourselves along her way and walk with her as she sets forth to re-establish who she is after life-altering loss. She is both brave and imperfect; she both surrenders and takes control; and, after her world becomes unrecognizable, she shows us a fiercely loving mother trying to find her way.

We gravitate to memoir for inspiration. In The Suitcase and the Jar, readers will find a quiet and comforting whisper, one that reminds us that, “If I could do this, I could do anything” (p. 9). It is a devastating, poetic, and ultimately beautiful meditation on living after loss.

*

Carys Cragg is the author of Dead Reckoning: How I Came to Meet the Man Who Murdered My Father (Arsenal Pulp Press), a 2017 Globe & Mail Best 100 Book of the Year and 2018 Hubert Evans Nonfiction B.C. Book Prize finalist. Carys is a faculty member of the Child, Family & Community Studies programs at Douglas College, and holds a BA and MA in child & youth care from the University of Victoria, where she studied girls’ diary writing as an act of spiritual self-care and young people’s experience of grief and loss. A graduate of The Writer’s Studio at Simon Fraser University, her essays, opinions, and reviews have appeared in The Globe & Mail, The Tyee, Understorey, Matrix, and the New York Post, amongst others. She lives with her son in Port Coquitlam.

*

The Ormsby Review. More Books. More Reviews. More Often.

Editor/Designer/Writer: Richard Mackie

Publisher/Writer: Alan Twigg

The Ormsby Review is a journal service for serious coverage of B.C. books and authors, hosted by Simon Fraser University. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Robin Fisher, Cole Harris, Wade Davis, Hugh Johnston, Patricia Roy, David Stouck, and Graeme Wynn. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. As of September, 2018, Provincial Government Patron: Creative BC.

Leave a Reply