#117 The belated legacy of Ka’kasolas

April 07th, 2017

REVIEW: Ellen Neel: The First Woman Totem Pole Carver

An exhibit at Legacy Gallery, Victoria, BC

Reviewed by Megan A. Smetzer

*

Between January 14 and 1 April 2017, the University of Victoria’s Legacy Art Gallery hosted an exhibit, Ellen Neel: The First Woman Totem Pole Carver, curated by Carolyn Butler-Palmer of the Art History Department at the university.

Megan Smetzer, who visited the exhibit for The Ormsby Review, assesses the belated legacy of Ka’kasolas, Ellen May Neel (1916-1966), the Kwakwaka’wakw artist who became the first woman carver in B.C. — Ed.

*

In 2014, UBC Press published Native Art of the Northwest Coast: A History of Changing Ideas, edited by Charlotte Townsend-Gault and Jennifer Kramer. This seminal volume, over a decade in the making, is notable for many laudable reasons including its historical depth, diversity of Indigenous and non-Indigenous perspectives, and range of subject matter.

For all its breadth, however, there is one significant omission that sums up the historiography of Northwest Coast cultural expressions — a lack of engagement with issues of gender.

Of the more than 800 excerpts framed by over thirty essays, only two address the positioning of Indigenous women and their cultural expressions within and outside of these histories.

With this in mind, it is thrilling to see in the first months of 2017 no less than four exhibitions devoted solely to the artworks produced by Indigenous women.

With this in mind, it is thrilling to see in the first months of 2017 no less than four exhibitions devoted solely to the artworks produced by Indigenous women.

In Vancouver, Coast Salish artist Susan Point at the Vancouver Art Gallery and Judith Chartrand, Cree ceramicist at the Bill Reid Gallery of Northwest Coast Art; Cree photographer Meryl McMaster at the Richmond Art Gallery; and Kwakwaka’wakw carver Ellen Neel at the Legacy Gallery in downtown Victoria.

Is it because, to paraphrase Prime Minister Justin Trudeau, it’s 2017?

Though four simultaneous exhibitions are not enough to counter the long history of women’s marginalization within the sphere of cultural production, might they indicate that at long last, we’ve reached a turning point?

It’s ironic, given that Ellen Neel began pushing against these boundaries over ninety years ago when, aged twelve, she began carving.

Ka’kasolas, Ellen May Neel (1916-1966), in many respects, was a woman ahead of her time. Granddaughter of one of the most renowned Kwakwaka’wakw carvers of the twentieth century, Yakuglas/Charlie James, she transformed the skills she learned from him into a range of materials and forms that enabled her to raise her large family in an era of rampant discrimination.

Ka’kasolas, Ellen May Neel (1916-1966), in many respects, was a woman ahead of her time. Granddaughter of one of the most renowned Kwakwaka’wakw carvers of the twentieth century, Yakuglas/Charlie James, she transformed the skills she learned from him into a range of materials and forms that enabled her to raise her large family in an era of rampant discrimination.

Neel was also a vocal proponent for the recognition of Indigenous art as “a living medium of expression” as it had been for generations.

Over the years her work has been dismissed in the literature as mere souvenirs, reassessed as groundbreaking, and at long last, embraced for the complexity it embodies, both in terms of the historical context out of which it emerged, as well as the legacy it engendered for her family, her community, and Northwest Coast cultural expressions generally.

This small but engaging exhibition begins with an artistic genealogy illustrating the generations of artists related to and inspired by Neel, including the exhibition’s two curatorial consultants, grandchildren Tla’tla’klalis, David Neel and Ika’wega, Lou-Ann Neel.

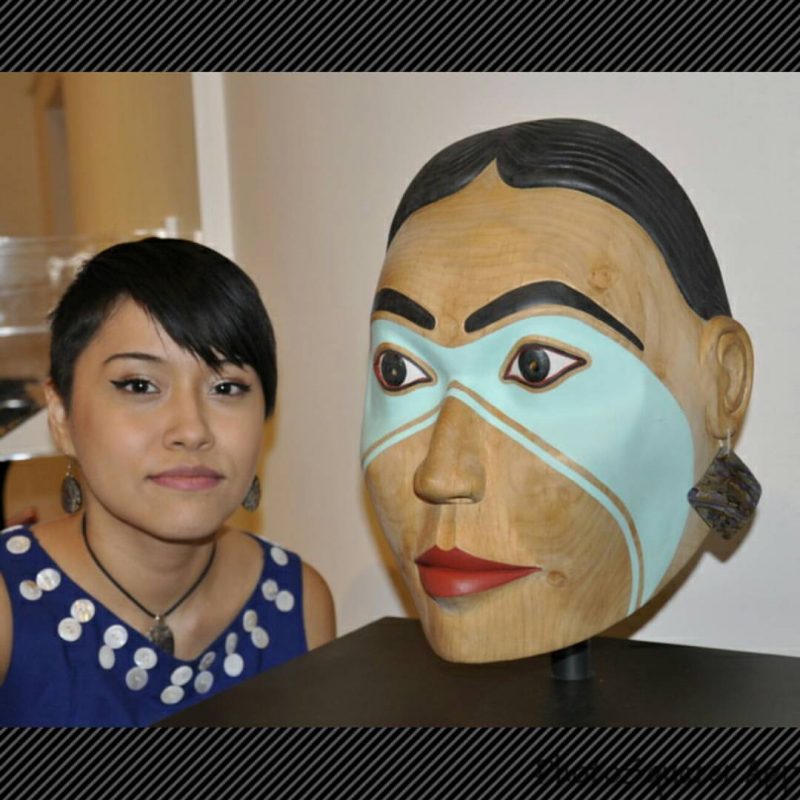

The exhibition is organized by grouping together different types of output – a mask of Dzonaqua, jewellery, miniature totem poles — including the Totemland pole, Totemware china, textiles, and silkscreen prints. Interspersed throughout the space are works by her children, grandchildren and great-grandchildren, including the mask that welcomes the visitor to the exhibition, carved by David Neel to represent his grandmother.

Informative wall texts both historicize and contextualize Neel’s prolific output and acknowledge the groundbreaking work she accomplished as an indigenous woman artist.

Family members loaned the majority of the work in the exhibition, which not only testifies to the collaborative relationship between the curator and Neel’s descendants, but also calls for a subsequent retrospective exhibition that brings even more of her oeuvre together — including monumental poles and items held in museum collections.

One of the works perhaps most familiar for those raised in British Columbia, is the “Wonderbird Pole” commissioned in 1953 for the White Spot restaurant in White Rock.

Accompanying the pole is a story, written by Neel, that describes the white rooster, who had to accomplish something truly extraordinary to be placed, wings outstretched, on top of a pole depicting salmon, killer whale, and thunderbird.

According to the “legend,” the rooster thought so hard about what to do to achieve this goal that he laid an egg, thus granting him the highest position on the pole. One wonders if Neel accepted this commission with humour, knowing full well that the “low man” on the totem pole, widely regarded in popular culture as the least important, is actually considered the most significant as it holds everything else up.

The rooster, literally standing on the shoulders of those beings with significant physical, cultural, and spiritual meaning, suggests a more complicated understanding of the relationship between Indigenous peoples and the settlers who came later.

Ellen Neel’s artistic output and advocacy work contributed to the contemporary recognition of Indigenous cultural expressions, whether produced by women or men, as responsive to their time and context.

Though it has taken until 2017 to reach what feels like a critical mass of exhibitions devoted to women artists, a great deal of work remains to be done in order to restore the balance central to many coastal Indigenous communities.

This exhibition, a collaborative work between an institution and a family, is a step in the right direction.

*

Megan A. Smetzer is an independent art historian based in Vancouver. She teaches, publishes, and lectures primarily on historical and contemporary Northwest Coast Indigenous art, focusing on the cultural expressions of women. She is currently co-writing an essay on this topic for an exhibition at the Minneapolis Institute of Arts on Native American Women Artists. She is also working on her book entitled Painful Beauty: Tlingit Women, Beadwork and the Art of Resilience. In addition, she is the project manager for Border Free Bees, a SSHRC development grant that uses public art and ecology to bring attention to the plight of wild pollinators and empower individuals and communities to engage in solutions to reverse habitat loss.

Judy…not Judith.

Gilakas’la, Megan!