Ormsby #121 A 100-mile crime novel

Speakeasy, according to our reviewer, affords us "a good crime spree" and resonates with B.C. locales.

April 17th, 2017

Alisa Smith's cryptanalyst heroine is "caught in the cat’s paws of history and ambition."

From Alisa Smith, co-author of The 100-Mile Diet, comes a tale of WW II espionage that takes place roughly within a 100-mile radius of Vancouver.

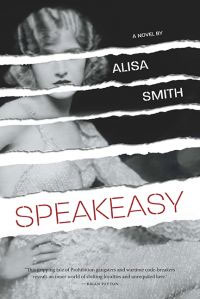

REVIEW: Speakeasy

by Alisa Smith

Madeira Park: Douglas & McIntyre, 2017.

$22.95. 978-1-77162-066-6

Reviewed John Douglas Belshaw

With her partner and co-writer James MacKinnon, Alisa Smith recounted their year-long attempt to eat only foods grown and produced within a 100-mile radius of their Vancouver apartment. Their collaboration, The 100-Mile Diet: A Year of Local Eating (Random House 2007), received the Roderick Haig-Brown Regional Prize at the 2008 BC Book Prizes.

Now she’s gone solo for her first novel, Speakeasy (D&M 2017), which mostly takes place in the Pacific Northwest during World War II, with flashbacks to the Depression. It follows Lena Stillman who has switched from being an undetected outlaw in the Bill Bagley gang during the Depression to working as a code-breaker at the Esquimalt naval base in a position to know military secrets. When she is assigned to find a spy at the base, her world turns even more complicated when her former underworld boss, Bagley, is sentenced to hang. The story is inspired by some historical facts: there was an infamous bank robber in the 1930s named Bill Bagley. He did have a female accomplice, never named, but the lead character of Lena Stillman in the novel is fictional. Smith did have a great aunt who worked as a code-breaker on the West Coast during World War II. In his review, John Douglas Belshaw praises both the heroine and Smith’s fictional debut, but takes exception to some mishandling of history. – Ed.

Now she’s gone solo for her first novel, Speakeasy (D&M 2017), which mostly takes place in the Pacific Northwest during World War II, with flashbacks to the Depression. It follows Lena Stillman who has switched from being an undetected outlaw in the Bill Bagley gang during the Depression to working as a code-breaker at the Esquimalt naval base in a position to know military secrets. When she is assigned to find a spy at the base, her world turns even more complicated when her former underworld boss, Bagley, is sentenced to hang. The story is inspired by some historical facts: there was an infamous bank robber in the 1930s named Bill Bagley. He did have a female accomplice, never named, but the lead character of Lena Stillman in the novel is fictional. Smith did have a great aunt who worked as a code-breaker on the West Coast during World War II. In his review, John Douglas Belshaw praises both the heroine and Smith’s fictional debut, but takes exception to some mishandling of history. – Ed.

*

When last we met our author, Alisa Smith, she was hoovering up everything edible within 100 miles. The locavore’s locavore has now moved on to an equally delicious diet of deception, betrayal, violence, and decryption.

Given that Alisa Smith’s day-job is in forensic accounting, perhaps this leap of literature is undestandable.

In this first novel, which borrows heavily from real events, Smith recovers the factual personality of Bill Bagley, a mostly-unremembered depression-era bank robber and an unrepentant scoundrel, and his “Clockwork Gang” who were on the run in the Fraser Valley. In those days, the police encouraged locals to “Follow the woman” to solve the crime spree. Cherchez la femme. This hint of a gun moll, this scent of a woman, gave Smith the idea of her protagonist, Lena Stillman: a tough and smart — though never quite smart enough — character caught in the cat’s paws of history and ambition.

This is a tale of two parts. One thread follows Bagley’s gang of 1930s bank robbers and safecrackers. The other charts the ex-moll’s career as a code breaker with the Navy in World War II Esquimalt. The whole is united in the theme of discretion. Hence the title of this book is pleasingly clever–and ironic. As everyone knows, loose lips sink ships. And bank heists work only if no one flaps their gums too much, see? Set partially within the Prohibition era (that gave rise to the speakeasy, where alcohol was illegally consumed), this novel is about people who don’t dare speak easy.

Secrets beget secrets, of course. In 1941-42, cryptanalyst Miss L. Stillman is one betrayal away from serious jail time. Her former beau, the Clockwork Gang’s crazy dangerous ringleader, is staying in the New Westminster Penitentiary at His Majesty’s pleasure and soon to face the gallows. Will he sell out Lena to keep the hangman at bay?

Lena narrates the wartime chapters, which alternate with an account of her adventures in the gang. Those are delivered by a second, more spectral voice, that of Bagley’s bottled-up accountant and confidant, Byron Godfrey. Although the gang’s roost is in Seattle, it is their escapades north of the 49th that make their story, recruit their moll, and doom their leader. Nanaimo and Harrison Hot Springs are their targets – and they become Bagley’s Austerlitz and his Waterloo.

The effect of these parallel yet out of synch storylines becomes increasingly effective. Lena’s present-time, 1940s voice has the urgency of someone nervously watching mayhem unfold on a global scale. As she cracks cyphers that might save sailors’ lives or breaks Japanese transmissions announcing which ship has been sent to the bottom at Midway, she’s also trying to read the signals being sent by conniving colleagues, suspicious supervisors, and distant lovers.

Working in a bunker, living in a dorm, and rarely even on the streets of Victoria, Lena’s focus narrows until she can barely see at all.

Godfrey, on the other hand and in another decade, is secretively journaling his extraordinary life as a rookie bank robber. This is a life lived large on the lam, and then, from time to time, electric with immediacy. There’s no imagined chaos on the horizon: the guns blazing around Godfrey — and young Lena — in 1932 are real. The harm that Godfrey records is of their own making.

Enter historical waters, however, and you have to know your footing. Parts of what became the “Lougheed Highway” (p. 134) existed in the 1930s, but the road itself wasn’t commissioned until 1941, much too late for the Clockwork Gang.

The phrase “moral compass” (p. 89) seems to me of recent vintage and out of place before mid-century, as does “brainiac” (p. 161), the portmanteau of “brain” and “maniac” coined for a Superman villain in 1958.

Lena anticipates that there will be more divorce after the war, “which had changed people.” Already? By the summer of ‘42? Divorce wasn’t easily obtained before P.E. Trudeau’s 1968 reforms and Lena does not own a crystal ball. If she was more true to her times, she might have safely predicted a spike in bigamy.

On another historical front, Bagley justifies his raid on the Harrison Hot Springs resort because it’s full of rich snobs, including “Dunsmuir, the coal millionaire, along with his wife” (p. 135). And Bagley doesn’t like Dunsmuir because he’s a “fucking slave driver.” Assuming we’re talking about James Dunsmuir, well, he’s a dead slave driver, having died in 1920.

These criticisms notwithstanding, Speakeasy is a satisfying caper and promises to be the first of at least two Lena Stillman stories. In Stillman – the excitable young woman who becomes an expert at being self-contained — Smith has created a potentially durable character. A good crime spree and global espionage, it seems, are like food: best when locally sourced.

*

John Douglas Belshaw teaches Canadian history at Thompson Rivers University. Among other accomplishments, he is the co-author, with his colleague and spouse Diane Purvey, of Vancouver Noir: 1930-1960 (Anvil, 2011). Belshaw makes his home in Vancouver’s East End where he dreams of going on a crime spree and completing his first novel.

The Ormsby Review. More Readers. More Reviews. More Often.

Reviews Editor: Richard Mackie

Reviews Publisher: Alan Twigg

The Ormsby Review is hosted by Simon Fraser University. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Robin Fisher, Cole Harris, Wade Davis, Hugh Johnston, Patricia Roy, David Stouck, and Graeme Wynn.

—

BC BookWorld

ABCBookWorld

BCBookLook

BC BookAwards

The Literary Map of B.C.

The Ormsby Review

Leave a Reply