Talk the talk; walk the walk

May 20th, 2017

FOREWORD

Anyone who has lost a beloved partner will know the debilitating and overwhelming nature of that loss. When my husband died suddenly and unexpectedly, I was knocked off my feet. In the freshness of grief, I waded through the tasks that accompany the loss of a spouse—notifying friends, arranging a memorial service, filing legal paperwork—aware of a more daunting job that lay ahead. I had a book to finish writing.

When I met Derek, I found that he didn’t engage in conversation like most people do, sharing casual anecdotes. He rarely answered questions directly, either. This made him seem inscrutable. I learned that he wasn’t evasive, but private. He carefully considered his words, which he often delivered in the form of a story, and only if he sensed a measure of readiness from his audience, be it a room full of people, or just one friend. Even me. Otherwise he just wouldn’t bother. This wasn’t disrespectful; he felt that people’s need for quick answers was a reflection of their own insecurity. For him, every story had a spirit, which must be honoured.

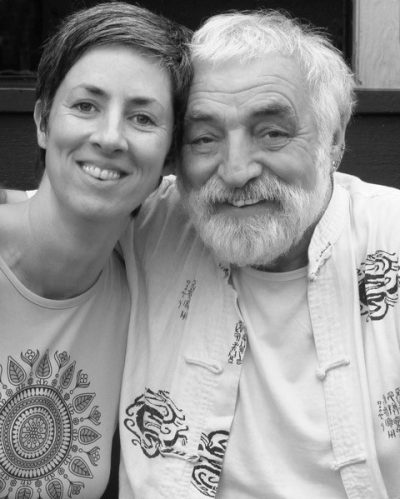

Derek put pen to paper and recorded some of his stories. With enough encouragement and goading by folks who wanted to know more about their friend, father, lover or guru, he began to shape this material into a book. I started helping with the project in 2004, and our long, sporadic, stimulating, and sometimes intense working relationship evolved alongside our personal connection: from mentor and student to collaborators, from friends to lovers, and then spouses.

At times I took dictation; at times I honed pieces he’d already written. Derek would read what we were working on aloud, needing to feel the words, not just recite them. If a passage felt flat, one of us—or both—would rewrite. We knew we were finished a section when we sat back and marvelled, Who wrote that? The stories were still his, but now it was our book. After seven years, it seemed that with just a few more short chapters we’d be finished. But then—

With Derek’s sudden death, the project was now completely in my hands. And as intimate as we had been, and as often as I’d been able to finish his sentences, I didn’t know how to complete it alone. After much contemplation, I sensed he would somehow guide me through the process, but I needed time to regain my balance.

Eventually, when I found my footing, I began to envision the book in a new light. Although Derek never intended to write a spiritual self-help manual or an autobiography, there were lessons in his stories, which I knew would speak most clearly in the context of his life. I needed to paint a more complete picture of this charismatic figure, the peace pilgrim with his larger-than-life calling and very human shortcomings.

I unearthed several boxes from our garage and found a wealthof material: photographs, videotapes and cassette recordings of interviews and workshops, as well as some hastily scribbled notes, a few diaries, and letters filled with tenderly scribed passages. His faded words revealed a younger, more idealistic version of the man I had married, engaging as ever, curious about life, and quick to laugh. As I read, I recognized a spiritual awakening. A hard-working young man’s worries about the doing aspects of life, the struggles of raising a family and paying the mortgage, were gradually replaced with questions of being. He spoke of love, responsibility, letting go, and finding peace—inside and outside himself.

My discoveries were exciting and rewarding but gave me a sinking feeling at the same time. The more facts I accumulated, the more the process felt like assembling a giant jigsaw puzzle that just kept growing. “How far along are you on Walking to Japan?” friends would ask, and I’d have to admit that I really didn’t know. I had lost perspective. So, I chose to redirect my focus temporarily, and went to live overseas for six months, spending every day walking until I tired myself out.

Gradually, through the rhythm of my feet everything came clear, and by the time I returned home to Canada I was ready to work again. I could hear Derek’s voice and put it to paper, though at times I wondered who was really speaking. “Is that really you?” I asked aloud, half hoping for an apparition, half feeling ridiculous for doing so. I could feel Derek’s amusement at my dilemma, as if he were giving me a gentle push.

And then I heard: I trust you, so trust yourself. Besides, is it really that different now that I’m dead?

I had to laugh. “Easy for you to say!” I shot back.

My process spanned years, and there were times when I struggled. Occasionally I had to weigh Derek’s portrayal of an event against someone else’s, or against objective facts. I wanted precision. But to my husband, the big picture mattered more than specifics. So I have tried to stay true to his vision and his memories, while being as accurate as possible. However, since life is messier than books can afford to be, some of the names, timelines and details have been altered or merged in the interest of privacy, clarity and flow. And although Walking to Japan is Derek’s life story, in his voice, you’ll find that I appear from time to time, speaking in my own voice (indicated by a different typeface). I hope this is not an intrusion, but adds to the big picture.

When Derek told me, a few years before he died, what he wanted to call the book, I laughed. How cheeky, I thought. “The only problem,” I told him, “is—what if someone picks it up thinking it’s an actual guide to walking to Japan?” Derek peered at me over his reading glasses, one eyebrow raised. Oh, how I miss that look!

So, no, it’s not a guidebook, if you’re wondering. Derek didn’t care about how to get from A to B, but how his mind and heart were opened along the way.

*

Here is the Preface by Derek Walker Youngs

PREFACE

Dreams are important, not because they might come true, but because they take us places we would never dare go, places we can’t even imagine. Goals are rigid and planned, but dreams—they’re exible, mutable, unpredictable.

I never dreamed of becoming a peace walker, but I dreamed of more. at dream pulled me along like an invisible hand, and it took me from walking for peace to talking the walk, on the radio and onstage, addressing huge groups of people with dreams of their own.

When I tell a tale from the road, there are always questions. Occasionally someone will pique my imagination or make me reflect deeply. But often people ask the same old things: “How many miles have you walked? How fast? How many pairs of shoes have you worn through? Where does your money come from?” I see that these questions are sometimes less about me than the person asking. What’s revealed are their priorities in life, their concerns, their insecurities. As innocent as these questions are—because of course it’s not every day you meet someone who’s walked across entire countries—I try to dodge them. I don’t mean to be flippant, but I’m not all that interested in the how manys, or even the hows. The how of my journey is just one foot in front of the other. What interests me more is why. I walk because it is my life. It’s no longer something I do; it’s who I am. It’s everything: passion, loneliness, confusion, frustration and joy.

The questions I ask myself are the most important. I have a lot of them. Questions can keep me awake, aware of my own motivations and limitations. They keep me engaged in the process of trial and error, and that is how I learn. I’ve never enjoyed playing by others’ rules—religious rules, societal rules, political rules. ey seem arbitrary and designed to stop people from thinking for themselves, so I have had to navigate through everyone else’s versions of what’s right and my own way. What do you really believe, Derek? Who is this lover of life? Who is this destroyer? How can you make a dfference? What are your dreams for yourself and the planet?

When I speak in public, I try to get people to think about this stuff. But then it’s question time, and I hope to hear something new. One day, I did: “Do you plan to write a book?”

The question both excited and terrified me—a good way to recognize a dream, if there ever was one. So I set out to claim it. I started by penning letters to friends, and then quarterly bulletins which I circulated for several years. This kind of writing came easily. But when I tried to write anything long or serious, my hands froze and my thoughts scattered like leaves in the wind. Every attempt just confused and discouraged me. I wrote poems, researched, and walked around libraries, hoping to soak up the right vibes to get me started. I did everything but write a book.

What was I doing? I wasn’t a writer! Frustrated and lost, I accepted help from a screenwriter, Katherine. “OK, Derek, let’s start with the basics,” she said. “Who are your favourite authors?” I froze. Maybe if I didn’t answer, she’d forget the question. No such luck. “Your favourite authors?” she repeated.

Heart pounding as it hadn’t since being called up before the headmaster in grammar school, I stammered, “I … uhh … don’t have any. I haven’t read a whole book in almost, um—25 years.” Katherine’s eyebrows rose like startled crows taking flight from a nest. “The world was going crazy back then,” I blurted. “Just like now, I suppose. Newspapers and books were full of violence—the Cuban Missile Crisis, the Kennedy assassinations, Kent State, the Watts riots, Charles Manson. So much bad news, and I was powerless. I had to stop reading before I lost my mind!” She stared at me blankly, saying nothing. Shame turned me queazy. No one in their right mind would admit to not reading books, I thought. Staring at the ground, I shuffled my feet, resisting their impulse to flee. Silence, at that moment, was definitely not golden but pitch-black.

Glancing up at her face, I was certain I could read her thoughts. Sure, Derek. I’m a professional writer, a literature scholar, and I’m still struggling to get a book published. And you—a guy who doesn’t even read books—you’re just wasting my time!

After a long pause, her mouth opened and I braced myself. At last she spoke. “Oh.” I imagined all the disappointment of the world in that one small sound.

How can such a tiny word carry so much power? Katherine meant nothing by it, but I let that “Oh” sabotage me. For years I was intimidated by the mysterious world of books.

And then, I met Carolyn.

Now, finally, my stories are here for you to read. I hope they give you a chance to wonder, to laugh, and to think about your own story. I invite you to walk with me, and be part of a dream—a dream that came true and continues to take me to places I could never have imagined.

[Distributor: Ingram Spark / 978-1-77302-273-4]

Leave a Reply