My Private Italy

In his second memoir-as-social-history piece, after My Private Chinatown, Grahame Ware recalls falling in love with Elle, at age 21, at the family-owned Nina Rosa restaurant on Hastings.

April 18th, 2019

Interior of Nick's a long-lived spaghetti house restaurant (1955-2017).

Ware’s odyssey of cuisine Italiana is rooted in the east end of 1950-70s Vancouver with stories of restaurants, nightclubs, family, love, travel and discovery.

MEMOIR: My Private Italy

by Grahame Ware

*

We are delighted to present “My Private Italy,” the second instalment of Grahame Ware’s social history memoir, a larger project with the working title In the Moonshadows of My iMac.

The first instalment, “My Private Chinatown,” was published in the Ormsby Review #501 (March 08th, 2019).

In “My Private Italy,” Grahame Ware reveals how his family’s Italian friends in East Vancouver, led by their gardens, cooking, and restaurants, helped put tinned concoctions of Chef Boyardee aside for the fresh tomatoes, garlic, smells, and spirit of authentic Italian cooking. Out of the hypnotic frog symphony of Vancouver’s very east end in the early fifties, Italian cuisine manifested itself in Grahame Ware’s sensibilities.

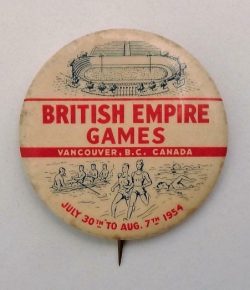

His English war bride mother, Ruby Ware, started cooking Italian food and Grahame’s own youthful Italian connections helped them both move away from dour and staid postwar and post-colonial East Vancouver — from a small city of war vets, war brides, the British Empire Games, the Empire Stadium, and memories of Depression-era hardship — to embrace a vibrant transplanted Mediterranean cuisine and foodscape.

From Kay DiCastri’s Rigatoni casserole to Tony Dimorn’s cooking lesson, our memoirist experienced the food culture of Italy first hand from them in East Vancouver. It all started with the contact high he experienced as a little kid with Papa Paolo’s San Marzano tomatoes — Ed.

*

Little did I know that growing up in East Vancouver in the early fifties on Cassiar and Third Avenue would infuse me with Italian sensibilities. As a Canadian kid from a Cockney war bride mum and an RCAF Alberta-born dad, my postwar multicultural membranes readily absorbed the juices, herbs, and spices of Italiana like freshly boiled pasta.

Little did I know that growing up in East Vancouver in the early fifties on Cassiar and Third Avenue would infuse me with Italian sensibilities. As a Canadian kid from a Cockney war bride mum and an RCAF Alberta-born dad, my postwar multicultural membranes readily absorbed the juices, herbs, and spices of Italiana like freshly boiled pasta.

Vancouver was a quiet town then and, depending on the weather, distant sounds were clearly heard in the low to no-car landscape. The Nine O’Clock Gun in Stanley Park could be heard nearly every night. But Vancouver was getting noisier, more boisterous. Just blocks away from our home, Empire Stadium had been constructed in 1954 as the centrepiece of the British Empire and Commonwealth Games.

The same year, this stadium became the home field of the BC Lions for their first year in the Canadian Football League. “The Lions will Roar in ‘54” became a marketing slogan. And roar they did. Empire Stadium acted like a large megaphone pointed skyward bringing a mass of hysterical cacophony to our porch fifteen blocks away. It was an astonishing sound. My childhood senses were alive to this new and noisy edge of Vancouver. And, despite the massive cheers and jeers of the Lions’ fans, it was the fragrance of family meals in the neighbourhood that quietly and aromatically seduced me.

Harry & Kay DiCastri lived just down Cassiar Street where its, and Vancouver’s, boundary ended in a deep ditch that demarcated a wet, willow-tangled bush of several acres. It was the lowest point in the area and was once referred to as Frog Hollow. This was the site of the pre-401 (later Trans-Canada) freeway, on the quiet eastern fringe of Vancouver. In the early spring, the complex and hypnotic sound of the thousands upon thousands of frogs held sway through the night and into the sleep and dreams of the neighbourhood. Soon the surrounding ditches and open waterways were enticingly mucilaginous with frog eggs and tadpoles. They felt like tapioca in my fingers as I waded though the ditches in my gumboots. It was heaven, even more so when they spilled over the tops of those Army & Navy boots. I laughed with joy about this. My mum? Not so much.

Bulrushes were everywhere and we stole kerosene from storm lanterns that adorned the City of Vancouver’s old work trailers. With our pocketknives, we cut them about two feet long. Once dipped and soaked with this flammable booty, we’d make torches of them and stomp into the wet woods at night and scare the raccoons and opossums. But a big works project soon drained the swamp and the soundscape from this zone in anticipation of the new freeway. The massive choral symphony of frogs was reduced to an amphibious chamber choir. The sounds of cars could now be heard well into the night.

From the bottom of Cassiar Street, the prevailing breezes of fresh, moist air brewed in the swamp and woods carried the fragrances of Kay’s cooking up the block to our house. One Saturday night Kay DiCastri feted us with an Italian meal — a rigatoni casserole. It was a workingman’s feast and my dad was delighted. Somehow it was collectively decided that my mum would simply have to learn how to make this dish. As always, she was game. A few days later, off I went with her and Kay DiCastri to shop for rigatoni and all the related stuff on East Hastings near Nanaimo Street where there was a small enclave of Italian shops and stores, including . In short order, my mum perfected the rigatoni casserole — usually with ground chuck or hamburger meatballs. It became a staple meal, soul food as it were, in our house. It later evolved to become a touchstone dish in my family as well.

Bianca Maria’s Italian Delicatessen, East Hastings and Nanaimo streets, 1963

Typical Mid-Century Builder cottage, East Pender Street, Vancouver, with heat-retaining solid concrete stairs

Harry and Kay DiCastri weren’t the only Italians in our neighbourhood. I remember Papa Paolo, as he liked to call himself. He lived a few of blocks up the hill on the way to school. Being a chatty little kid I’d got to know Papa Paolo myself one sunny September day as I came home from school. As the grandfather, he lived in the basement with his family upstairs in their fifties Mid-Century Builder cottage. He was in charge of the yard and grew tomatoes up and around the huge concrete steps of the house. He had rigged up stakes and wires so that his tomatoes could grow and grow all season long. The solid concrete stairs – ten cubic yards’ worth, a contractor standard and what everybody did then — brought a lot of extra heat during the summer. This heat would slowly release during the twilight and lengthen the season for Papa Paolo’s favourite canner tomato variety — San Marzano.

Like so many postwar Italian immigrants, Papa Paolo was generous to a fault and would give you the shirt off his back if he thought it would help. Egalitarianism, not elitism, was the rule in those days. The plumber and the lawyer were essentially on the same ideological page in fifties Vancouver. Naturally, Papa Paolo gave me some tomatoes the first time we met. Crouching down to pick the ripe tomatoes and coming face to face with me he declared, “Smell them!” he beamed, and so I did. It was a contact high and an unforgettable moment. “For your mama,” he cautioned. I nodded.

We picked five or six and put them in my Lone Ranger lunch bucket. I was so proud of these fruits — so nicely fitted and so red. I knew my mum would be tickled. The taste of these ripe tomatoes with cheese in a sandwich was unforgettable. This was the moment I not only fell in love with the tomato but with the idea of growing vegetables. The radiant energy reflected in the face of Papa Paolo was the reward I sought. Growing food and gifting it seemed ideals worth striving for. That occasion was informal and spontaneous, lacking a ceremonial silver spade, but it still unearthed a future horticulturist with a passion for growing. A very long engagement ensued from that encounter with Papa Paolo, the tendrils of which are still wrapped around me — and still growing.

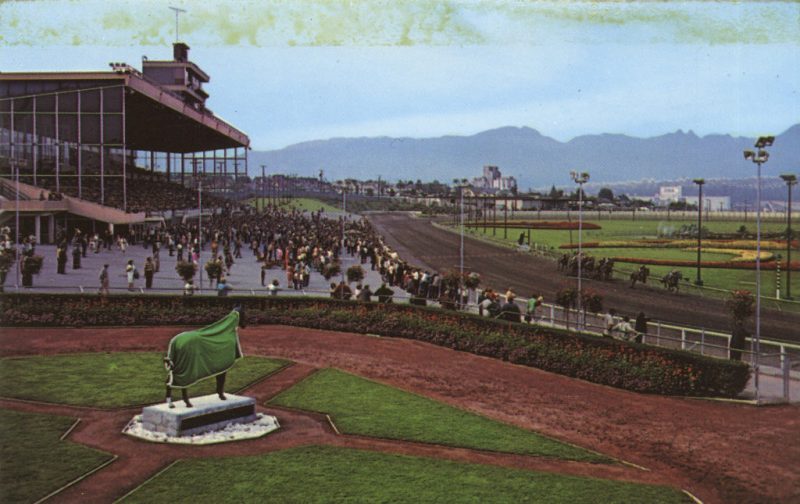

Besides sharing meals, my family and the Di Castris did other things. One time we went to the Exhibition Park (“Ex Park”) racetrack, in Hastings Park near Empire Stadium, on a sunny Saturday afternoon. It was one of the first times I’d seen people get collectively excited — especially Harry Di Castri. He loved the “ponies,” especially one called Princes Street. This horse had won many races in a row and somehow he just couldn’t get beaten, no matter how much lead they made him pack. This particular day, Harry bet large for the horse to place. Princes Street didn’t disappoint and won again, and somehow it paid more to place than to win. Harry was jumping up and down, his face red. Kay was slightly embarrassed but Harry didn’t care and gave her a big smooch. What a contrast with my stoical father!

When Harry calmed down, he went inside to trade the Ex Park’s paper for our fiat. On his return he said, “I made more money today on that horse than I did all week laying bricks! Thank you Princes Street…. We’re going out to eat!” Kay gave him an uneasy “you-shouldn’t-have” frown that Harry caught and laughed it off. He was enjoying his win and the attention, and he didn’t mind the expense, but he sensed the unease with his post-race bravado, so he shifted gears. Lowering his voice like he was sharing a secret, he said “My buddy Bruno says there’s a real good Italian place on Commercial. It’s a brand new … a family place. Nick’s Spaghetti House. Let’s all go. It’s onna me! Whaddya say?” He earnestly looked round and his eyes finally landed on Kay for approval.

“Family place, eh? Well … okay,” she said, and smiled to him and the rest of us. My mum and dad really couldn’t say no. After all, it was Saturday and time to have a little fun.

We skedaddled from the racetrack on down to Nick’s Spaghetti House. No surprise — it was fun and there was more food than I could eat. Nick Felicella made the rounds and introduced himself both in Italian and English. The rest of us smiled politely. Harry and Nick got on like a house on fire and talked horses. There’s something about Italians and racehorses.

As the meal wound down, the conversation picked up. Getting a little more serious, Nick said, “Gotta question for ya Harry. Whaddya call a cross between a octopus anna Wop?”

Harry suddenly looked unsure and shrugged, “I dunno.”

“I dunno either,” Nick said, putting his hand on Harry’s shoulder and looking even more serious. “But boy oh boy … it can lay bricks faster than anybody!”

Harry — who was a bricklayer — doubled over laughing, his lit cigarette crashing on the floor. More waves of laughter ensued at this.

“Never outa work!” Harry managed still laughing. We were all laughing hard by now. Boy oh boy … whadda time we all had. Whadda day!

*

As a young man, I worked in downtown Vancouver and lived on Victoria Drive (between William and Charles) in a basement suite. The house was huge thing and the landlord was a Swedish-Canadian logger-cum-carpenter. He’d bought the three-level mansion with a big downpayment from a few good seasons in the bush. You could do that in those days, whether in logging or fishing. All you had to do was to be young and strong, work your butt off, and, oh yeah, belong to a union!

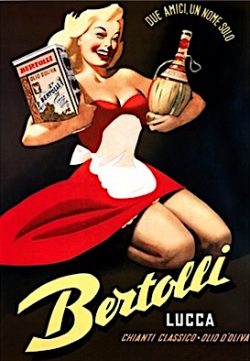

Once I moved in, I had to set up the kitchen and was delighted to find an Italian grocery store, Dimom Confectionary, just steps away at 1302 Victoria Drive. It was a nice building on the corner of Victoria and Charles with a wide door set at 45-degree angle and a cleverly constructed roof cover. It is now the home of Monarchy Boutique. The place had an ordered but unpretentious old world soul to it. The only object of commerce from an advertising point of view were two posters. The first was a pasta poster near the till on the wall; the second was for olive oil.

As for the pasta, the first thing that struck you as you walked in was that most of the space was given over to dried pasta. There was every type imaginable in every size and thickness, all denoted by numbers (no. 5, no. 7, no. 11, etc.). It was mind-boggling. They were arranged on simple, wide, wooden shelves — linguine, fettucini, spaghetti, penne, rigatoni, etc. Some of the packages were plain cellophane whilst others were in light cardboard boxes.

But it was the canned tomatoes that really caught my eye on the shelves against the wall. They were wrapped in gloriously coloured labels (in Italian) and funky erotic lite logos with voluptuous women with low-cut blouses and big smiles promoting both tomatoes and the company.

But it was the canned tomatoes that really caught my eye on the shelves against the wall. They were wrapped in gloriously coloured labels (in Italian) and funky erotic lite logos with voluptuous women with low-cut blouses and big smiles promoting both tomatoes and the company.

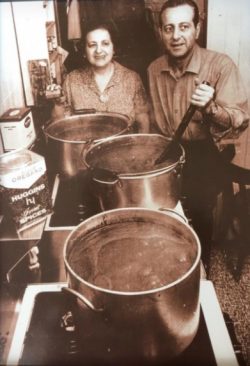

Tony (Anthony Dimorn) and his attractive, dark-haired wife lived upstairs. Behind a curtain on the store level next to the till was a small kitchen. It was in there that Tony gave me my first Italian cooking lesson, maybe because I came in all the time to buy pasta and tomatoes. I was experimenting and trialling with food and utensils. Like many a kid of my era, I’d had my share of Chef Boyardee beef ravioli in a can. But cooking from scratch was a new thing for me.

Maybe, too, Tony decided to teach me how to cook his way because I looked like a sad, bedraggled hippie who could use a little more energy or bulk.

“Hey, kid, wanna know how to cook real Italian food?” he said.

“Sure!”

“Okay… This is how ya do it, kid.”

With that he began sautéing ingredients in olive oil and humming some melody as he did so. He was in a happy mood and not embarrassed at all about humming or singing a few bars. It was fun. He explained:

With that he began sautéing ingredients in olive oil and humming some melody as he did so. He was in a happy mood and not embarrassed at all about humming or singing a few bars. It was fun. He explained:

Always start with the peppers, then onions, and then the garlic — burns too easily and spoils the flavour — remove them and then cook your meat or shrimp and add herbs (oregano and rosemary), and then blend it and stir it all together for a few minutes before adding your tomatoes and sauce, and then quickly lower the temp to a simmer for 10-15 minutes.

It was all done in a large cast-iron frying pan. As for the pasta, Tony said that he didn’t like it undercooked so he had it boiling for about fifteen minutes. Now was the moment of truth after 25 minutes of work. Out came two big bowls and we sat down at a little square table. He served me and then we ate.

“Eh?” smirked Tony, arching his dark eyebrows. “Whaddya think…thatsa good?”

“Oh yah!” I said.

Tony then laughed. “We have a kinda word for this. And…”

“Yah?”

Tony put his fingers together and then to his mouth, and then he let them fly away:

MWAHHH!

It was my turn to laugh. “Perfecto!” I retorted in one of the few Italian words I knew. That was what Tony taught me, and it was one of the best cooking lessons I had. But migawd I was hungry! There was a silence and satisfaction to the meal. We both knew this was great and didn’t have to say a thing.

At this point, I didn’t know Tony that well but after the meal he didn’t call me kid anymore. Out of nowhere, unexplained, he just started called me Sonny. How was I to object to that nickname? We then started talking over a glass of red wine he’d poured, about family and soon about my father from Alberta. Tony’s mood changed. He became serious and said:

Canadians don’t know how to have fun, Sonny. The men always seem to be sombre. Silent. Italians — we get a little drunk and we sing. Canadians get a little drunk and they want to fight! You’re different, Sonny.

In 1971 Tony Dimorn left. I never found out why because I’d moved before him. Pasquale Bruno took it over. I was crestfallen. He re-named it Bruno’s Grocery and he ran the pasta goods market that Tony had started using much the same approach. Obviously this was still a great place to get authentic dried Italian pasta, but the place had a different energy to it. The casual country soul of Tony’s short-lived venture had been jettisoned in favour of a cleaner and more urban Canadian look. The posters featuring the cheerfully voluptuous babes selling tomatoes and pasta — a grounding spectrum of images — had come down. A light had left the room. They were replaced with dreary posters for Coca-Cola, Export A, and Kool cigarettes. New fluorescent lights with their 60-cycle hum of monotony cast a grey Yankee look. Somewhat dazed, I stumbled around and, out of guilt, bought a few packages of fettucine and linguine, and then left. I never went back.

*

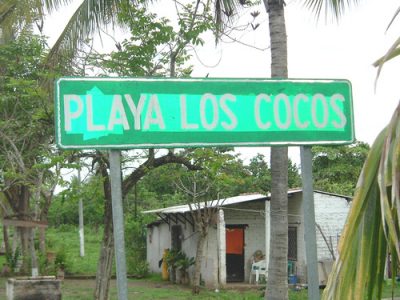

A few years later on a beach in Mexico (Playa de los Cocos, south of San Blas), I thought of Tony again as I made a fresh seafood pasta for a group of campers (Dutch and Danish) on the beach. I’d brought my own canned tomatoes and paste (the empty can of which later repaired my broken tail pipe for the long drive north!) and my cast-iron frying pan. It was all tucked away in my Renault 16. With some fresh caught camarones (prawns) and some peppers I’d bought at the San Blas farmers market, my white gas Coleman stove was singing on the beach under the coconut palm trees.

A few years later on a beach in Mexico (Playa de los Cocos, south of San Blas), I thought of Tony again as I made a fresh seafood pasta for a group of campers (Dutch and Danish) on the beach. I’d brought my own canned tomatoes and paste (the empty can of which later repaired my broken tail pipe for the long drive north!) and my cast-iron frying pan. It was all tucked away in my Renault 16. With some fresh caught camarones (prawns) and some peppers I’d bought at the San Blas farmers market, my white gas Coleman stove was singing on the beach under the coconut palm trees.

Atop the high bank, I could see out onto the Pacific where there was a natural phenomena unfolding. A returning migrant herd of giant manta rays rose up out of the water and slapped their fins on the water, making for a great display. We found out later from locals that they did this to get rid of parasites and leeches. There were hundreds of manta rays rising up and splashing down.

This amazing event underpinned a great al fresco cooking moment. It was an Italian cooking moment that also came full circle with the actual Mexican origin of tomatoes and peppers; both were introduced to Europe by the Spanish in about 1700 AD. I felt so good in this place with these new European friends. It was great to cook up such wonderful food. Somehow all the work I’d put in to get to this place and to this shore, with this vista, was worth it. My cooking skills had taken flight — from my mum, from my dad with his Boy Scout cooking for his patrol in the bush, and then to Tony. Now here I was cooking for an artsy, hippie Euro gang. 1974 was a great year to be young and in Mexico.

The arc of my energy was now experiencing the joyous vapour trail of my intention — namely, to cook in an authentic Italian way and knock it out of the park, meal after meal. From now on, it wouldn’t matter where I was, just like it didn’t matter to the Italians (or the Chinese) that they were immigrants in Vancouver. The cooking mantra was simple: use what components you have and cook how you know.

So here I was, quickly sautéing the camarones at the end of the sauce-making and then turning the heat way down to not overcook them. Tony’s happy cooking hum was with me again, only now I was the one singing, and it was a Donovan song I’d learned to play on guitar: “Sand and Foam.”

The sun was going down behind a tattoo tree

And the simple act of an oar’s stroke put diamonds in the sea

And all because of the phosphorus there in quantity

As I dug you digging me in Mexico.

Some of Tony’s and Papa Paolo’s Italian soul, their Mediterranean joy, had rubbed off on me. Their example was even more inspiring because I was able to share it with new camping friends from Europe. The look on their faces when they started eating was balm to my soul.

When we’d finished, inevitably and as if on cue, and with a relishing of the corniness, they said, MWAHHH! Laughter is always the best way to cap a meal.

*

But back to Vancouver and the post-Tony period. Because of him, my interest in Italian food deepened and I wanted to dine at Italian places. I was more than a little curious about a little house on Seymour, Casa Capri, a family place run by the Iacis. I’d stuck my head in the door a few times only to receive an unctuous rejection: “Sorry, all full up.” Naturally I was bewildered by seeing empty tables with RESERVED declarations on them. But I was too early for dinner. I was operating on working man’s time, I concluded. The reserved middle class would be in later.

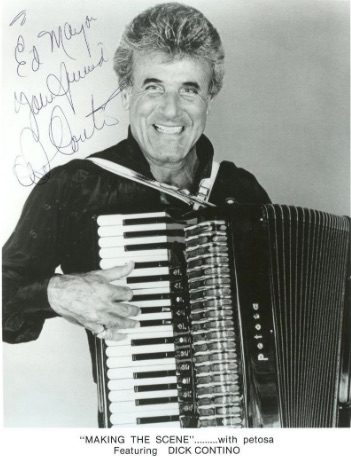

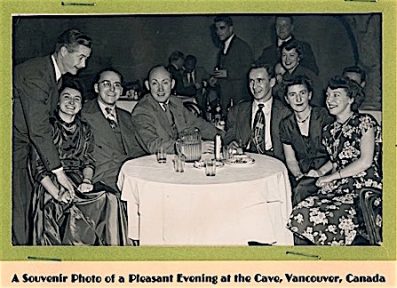

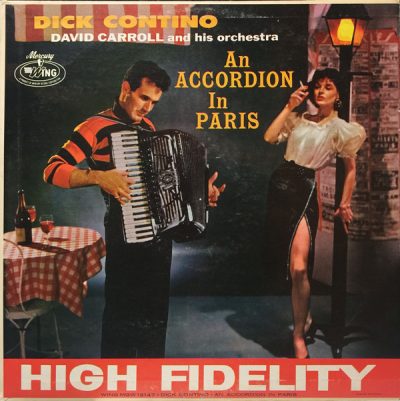

But I kept trying. I figured that a cold Thursday night would work but, dammit, this was the last time I was going to try. Surprise! “You’ve got to have the chicken cacciatore!” said the lady greeting me. She ushered me to a little table in the corner. I couldn’t believe it — I was in! I took my jacket off and then turned to see on the wall next to the table an autographed 8 x 10 glossy black and white pic of Dick Contino. He had a massive accordion slung around his shoulders. He’d written on the photo, “Great food! Dick Contino.” The writing was all loopy like a teenage girl. I smirked.

Here was Dick staring down at my chicken cacciatore as, several munches into the meal, I recalled the picture of Contino that my mum had taken in 1954 when she was a photographer at The Cave. It wasn’t at all like the pic that my mum had developed. Mum was very proud of her pic.

Here was Dick staring down at my chicken cacciatore as, several munches into the meal, I recalled the picture of Contino that my mum had taken in 1954 when she was a photographer at The Cave. It wasn’t at all like the pic that my mum had developed. Mum was very proud of her pic.

Eating alone has its benefits. I was able to unwind and sink into my thoughts. Somehow near the end of the meal I recalled my mum crying about that Contino picture. Yes … my dad had ripped it up and given her the ultimatum to quit the Cave. My brother and I were huddled in fear in the small bedroom in our house on Cassiar Street as the blow-up flared. My dad was shouting and my mum was crying. It is the first memory I have of my parents fighting.

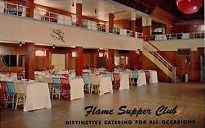

My mum’s pic of Dick Contino was definitely more intimate than the boilerplate glossy at the Casa Capri. I then remembered the torn and crumpled pieces of those steely eyes alone in the top of the garbage can the next day. It explains why soon afterwards Ruby left The Cave and started working at the Flame Supper Club off Grandview Highway and Boundary Rd. When asked why she’d left, the line for public consumption was that The Flame was closer to home and the hours were better. Mum had always waxed manic about her time at The Cave and her connection to Hollywood and glamour. The decision seemed so sensible yet something wasn’t right.

My reverie of times past was then broken.

“How’s the food?” asked the Casa Capri lady.

“Oh, uh … loved the red peppers and the tomato taste.”

“Ah,” she smiled, then added. “And, finely chopped sun-dried tomatoes and charred and pickled red peppers. Fresh garlic … hmmm?”

MWAHHH! I said with a little comedic flourish. She laughed. We took each other in for a moment then I said, “Any good live?” pointing at — almost touching — the photo. “I’ve only seen him play on Ed Sullivan.”

“Oh, Dick Contino, well he’s okay, I guess, in a vain, Hollywood kinda way,” she allowed.

“He came here a couple of times years ago with his mum and dad. His dad was a butcher. They ran a deli somewhere in California.”

That would have been about 1954, when he was reviving his career after his Korean War fiasco, and his appearance at The Cave was part of his revival that catapulting him to many Ed Sullivan Show appearances.

*

Into the drab postwar landscape of Vancouver my mum, Ruby Mae Miller, a cockney war bride from Greenwich, London, arrived in 1946 after a long ship and rail trip covering 8,000 miles. She was just twenty. Little did she realize that her husband, Dave Ware — eldest of fifteen kids with a Depression-era Prairie upbringing — was part of a dour, west coast working class environment. His emotional unavailability would eventually cost him his marriage. Dave took the dog-in-the-manger attitude to new heights.

Ruby arrived in Vancouver ready to give it her best shot. And that she did. She didn’t brook any male BS. She strode boldly through this time and place. On more than one occasion she was seen proudly sporting vivid, iridescent houndstooth slacks, a leopard skin pillbox hat and a mink stole with a gold lamé blouse. She was a blotch of vibrant asymmetrical colour in a black and white Rorschach town.

She smoked, and drove her Morris Minor hither and tither all the while encouraging women friends of hers to do the same. “Live a little!” she would say with slight admonishment, punctuated with her infectious cackle.

Think of Andrea Martin as Edith Prickly on Second City and you’re not far off. Only mum was better looking than Andrea Martin. She parlayed this vivacity into a gig as a photographer at the Cave Supper Club on Hornby Street. It was the first club in B.C. to be issued a liquor licence. Undoubtedly her work there added fuel to her fascination and abiding interest in all things Hollywood and entertainment. Strippers and the B-lister marginalia from the Vaudeville-cum-Hollywood circuit originally occupied the Cave stage, and Don Francks, the Iron Buffalo himself, sang there as a high schooler.

As it started to get better and better acts, The Cave’s popularity gained momentum. Thus the likes of Sammy Davis Jr. (the top act at the time), Tony Bennett, and Dick Contina came to the grotto-like establishment. As a result, it became the place for the wealthy and the curious to come and let their hair down. A quick study in her job, Ruby flitted from table to table with her camera and became a pretty good photographer. She fit right in. She once received a huge tip from K.B. Woodward (founder of Woodward’s Department stores) that she had to “clear” with my dad before accepting it, so as not arouse his suspicion or jealousy.

But Ruby was also a committed thrift shop junkie, always for great deals and sharing or giving her “steals” to others friends. For her, it was a sport that had started years earlier in postwar rummage sales, a common phenomenon in those days. Every church had them as fundraisers. One of her rummaging regulars was Kay DiCastri.

One of the things that mum liked to do was smoke — to “have a fag,” as she called it. She thought it relaxing, a way of getting things to slow down and talk and have a good gab. She was notorious for holding court. In later years, this exercise became tedious, but newcomers were always charmed.

*

It was a good night and the food was fine but I never went to the Casa Capri again. My local Italian ristorante, the Nina Rosa Cafe on Hastings, had ground beef stuffed manicotti that was outstanding. It was closer to home and, oh yah, I’d fallen in love with Elle.

Elle was a bank teller at the Bank of Montreal that stood on the corner of Hastings and Carrall. She was 21 — the same age as me — and she was a pure blond Swedish lady with blue eyes and full pink lips that needed no lipstick. Innocent and sweet as a summer’s morn, she liked to wear blue, white, or pink clothes and had a preference for pearls, big hooped silver earrings, and patent leather boots. She was a platitude of pop perfections that always aroused me. On top of it all she was a sweetheart. Somehow I always ended up in her line when depositing my paycheque from the Electric Meter Shop.

However, she was what we called straight (not a hippie). But she was quick to see the funny side of things and had a great laugh, and her smile was beyond wonderful. Maybe she was a hippie-in-waiting and just needed to get high and see the light? Things evolved naturally enough with us from a quick lunch at The Only Seafood to a dinner date.

The place we went for that first date was the Nina Rosa. It was my first planned, romantic dinner date that I can recall. Family-owned and run, Nina Rosa was both intimate and unpretentious with booths and tables that covered with the obligatory red-checked gingham tablecloths. The waitress always lit the candle when you sat down. The best thing about the food was that it was like home cooking.

Dinners with Elle at Nina Rosa’s became a regular kind of thing, something we’d shoot for during the week’s drudgery. Over dinners, eating at their little tables, I began to see that she was a lovely, attractive young lady. Being so close to her and learning to relax in that proximity, I would just breathe in her blond creaminess and innocently erotic aura. Over Chianti, which we discovered together, she would talk about my chocolate brown eyes. I wanted to completely inhale her! With my eyes on sticks, my desire must have been obvious to her. Towards the end of the bottle I managed to say, “You look so lovely tonight.”

“Aw, thanks.” We squeezed hands across the table and did a little gushing.

The look in her eye this evening had a little more depth. Thank you Chianti!

“The night is young,” she suddenly proclaimed. “Would you like to come back to my place?”

“Sure,” I said with an equal mixture of excitement and disbelief.

“It pays to be a gentleman” was the thought in my head.

Intimacy was amazing with her. She had everything a guy could want and then some. We became lovers and worked at it. Ah, but what work it was. Every time was more fun than the last. It was always the same and it was never the same. A sacred yet mystifying activity. All of the tension in my knees vanished when we made love. Making love helped both of us work through things. We were, after all, just working class kids and innocent (and confused) ones at that.

We saw each other for a while longer and then I found out from a teller at her bank that she’d been promoted and transferred to a new branch in Aldergrove. This was at exactly the same time as I had to leave, quickly, for another job in Surrey. Washing electric meter covers was over. Neither of us had time for a forwarding address or a phone number to make contact. She was gone. We were both gone.

There would be no farewell meal of manicotti at the Nina Rosa, the space where two wounded but hopeful young people came together and satisfied their collective hunger. A place where I was able to be a gentleman, and where she was elevated to my soft and pink lady (I’d memorialized Elle in a poem of the same name). The Nina Rosa was the focus, the intimate spot where light Italian accordion music played in the background and where working class people could have meaningful conversations.

We didn’t have to talk above the continuous and seemingly mandatory noise of “background” rock music as is the case today. The restaurant soundscape is brutal these days if you decide to eat out. It is, I’m afraid, mostly too loud to talk. You have to shout manically to be heard. Sadly, to get some quiet intimacy and class, you now have to pay a premium. But in its heyday, the Nina Rosa provided old-fashioned romantic dinners for young and old.

*

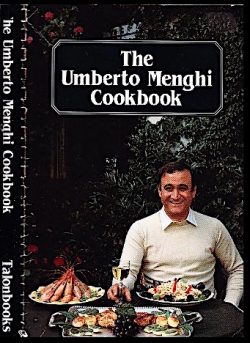

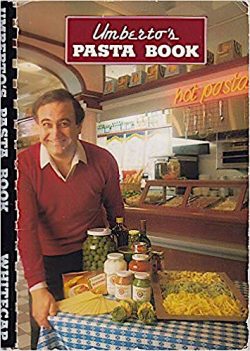

I kept trying to up my Italian dining game and worked on more than one occasion to get a table at Umberto, the flagship restaurant of Umberto Menghi, but to no avail. Thus, I was unable to compare how his food stacked up to Iaci’s Casa Capri or the Nina Rosa. However, I’m willing to hazard a guess that I would have been wowed.

I kept trying to up my Italian dining game and worked on more than one occasion to get a table at Umberto, the flagship restaurant of Umberto Menghi, but to no avail. Thus, I was unable to compare how his food stacked up to Iaci’s Casa Capri or the Nina Rosa. However, I’m willing to hazard a guess that I would have been wowed.

Umberto Menghi firmly embraces the philosophy or the concept of sapori. This term refers to the flavour of the culture or individuality of a regional culture. The French would have it broadly as terroir. This notion of sapori twinned with the posture of amichevole e divertente, or “friendly and fun,” is what drives the spirit of Italian food. In the emerging and experimental culture of the early seventies in Vancouver, this proved to be an irresistible formula for commercial success. People wanted more than just food from their dining experiences and, broadly speaking, Italians were providing it. And they are still doing so.

UBC’s International House is where Umberto Menghi, a real transformer of the Vancouver foodscape, got his start. While at UBC, he used to sing, croon, and carry on at their special evening food events. His extroverted nature gave him the confidence to try striking out on his own. His first venture, Casanova’s in Gastown, just didn’t generate enough interest and went belly up. He was too soon to the Gastown party.

His next venture, named appropriately enough Umberto’s, located in the Leslie house at Pacific and Hornby, would be his launching pad to success. He was attracted to its 1881 heritage quality and its colour. It was painted a strong, luminescent yellow by one of Vancouver’s original psychedelic rock groups, Mother Tucker’s Yellow Duck. Needless to say, the house stood out in the grey and green Vancouver landscape. A lot of consciousness-expanding product went in and out of the adjacent alley before Menghi arrived on the scene in 1973. I believe they supplied much of their illicit product to the West End.

Umberto Menghi’s la Cantina seafood restaurant, Hornby Street, Vancouver, July 1975. Courtesy of City of Vancouver Archives

And the next year he opened the seafood restaurant La Cantina on the north side of Umberto. He then, in 1976, built Il Giardino south of the yellow house which proved to be his mainstay, the beachhead from which he built his fortune. Menghi, a Tuscan, talks openly about his origins and start as a chef/ restaurateur in Canada in Umberto’s Kitchen (Douglas & McIntyre, 1995), for example:

On opening night at Umberto, Umberto himself was flying by the seat of his pants and by 8 o’clock had his confessional moment to the restless and hungry patrons. He only had a box of rack of lamb, one piece of veal, a box of tortellini and some salad fixings. He said:

“I’m sorry … but I am unprepared for the evening. I have enough food to feed you all but the choice is mine. If somebody, instead of getting aggravated, could go to the liquor store and get a bunch of wine — we’ll deal with it afterwards — let’s have a party! I’ll cook the same for everybody. And … it will be good.”

And it was — with five cases of Beaujolais.

Within six months Menghi was well on his way. To celebrate, he purchased a matching yellow Ferrari. The man with the yellow restaurant now had a yellow car! He has never looked back from that point in 1974 as he zoomed off to future success, his head cocked back and hair blowing in the momentum of his Ferrari and the benign breezes of English Bay.

Within six months Menghi was well on his way. To celebrate, he purchased a matching yellow Ferrari. The man with the yellow restaurant now had a yellow car! He has never looked back from that point in 1974 as he zoomed off to future success, his head cocked back and hair blowing in the momentum of his Ferrari and the benign breezes of English Bay.

Such was Umberto’s success that he published his first cookbook in 1982, The Umberto Menghi Cookbook. This was followed in 1985 by Umberto’s Pasta Book, and just as quickly in 1987 with The Umberto Menghi Seafood Cookbook, but the best written and most revealing of his books is Umberto’s Kitchen: The Flavours of Tuscany (1997).

And in the nineties he also began doing TV shows for The Learning Channel. You couldn’t help but learn from watching his shows. Umberto was now a brand and a local cooking phenomenon occupying the niche abandoned by the born-again, guilt-ridden Graham Kerr.

And, by this time too, a sea change had taken place in the eating and dining scene in Vancouver. It had all become rather high-powered and upscale spearheaded by the Italian theme and fashioned by none other than the Tuscan, Umberto Menghi himself.

*

Tony, the grocer, and Umberto, the cook-restaurateur, were both passionate about their customs and their food. I was lucky enough to experience their joy and see its importance. More and more now, I was the creator and not just the consumer of Italian food. More and more, I was a cook who used the ideas of Italian cooking to explore French, Spanish, and Japanese culinary styles and ingredients. Italian food and cooking were a portal to so much more.

As I have grown from a young man to an old man, I see how food keeps us real and healthy. Food is for nourishing our tired bodies and souls and for sharing the joys and tribulations of our work and play; for having that romantic window open up in one’s life to reveal a glimpse of what might be; for feeling emotions and sensations that always seemed out of reach and which, suddenly at some point in the meal come flooding in and are there to be grasped. Obviously food’s brother-in-arms, wine, had something to do with that as well.

It has all quietly — and sometimes not so quietly — seduced me. But my private Italy is not so private anymore. I have, in a small sense, become Italian. Like the air that surrounds and sustains us, the sensibilities of Italia are also invisible but, in my case, absolutely necessary for my life. Italy, it seems, is no longer defined by the ephemeral political boundaries of their leaders, or earlier of their misguided militarists, but by the soul of people who love to share their culture and their love of food. Cooks don’t make war, they nurture, and in so doing they make life better. This is why the lover in me exults in the act of cooking. It is a simple enough thing to do but the spirit of the act is the thing. As Leo Busclagia famously said, “Love is a verb – it’s not something you feel. It’s something you do.” That cooking is love is something I’ve known for a long, long time.

*

All is quiet now. In my kitchen I prepare another meal at the end of the day. The faint echoes of Tony Dimorn’s spirit begin to stir in me as I recall for the thousandth time his first lesson, his first words back on Victoria Drive. It seems almost unthinkable that his simple act of kindness, made to me so many years ago, would have such a stamp on my sensibilities. Just as Tony hummed when he cooked, now deep into my dinnertime reverie something astonishing takes place. Two more voices suddenly join the cook prep hum-fest: Kay DiCastri and my mum. They chime in with their spirit voices in what I can only describe as an Om Italiana. I’m smiling but completely still because I really can’t believe I’m experiencing this. I don’t want the trance to end by smirking in disbelief or having some snarky thought jolt me out of my reverie. I go back to cutting up the mushrooms with my old Henckels knife. I don’t care who believes this moment. It is wondrous.

The gift of a style and a time-honoured formula is singing tonight as I prepare the very same pasta dish that Tony made for me fifty years ago. Now I use more “sophisticated” ingredients: fire-roasted tomatoes, pesto made from sun-dried tomatoes, truffles, or basil, imported San Marzano tomatoes, capers, any number of wondrous cultivars of garlic, and even the best dried pasta from Italy that uses Farro wheat. But the essence hasn’t changed: use what you have and cook what and how you know. But, most of all, be mindful of your blessings to be in a kitchen filled with love and light and knowing the joy of this moment of becoming.

And tonight, in the moonshadows of my iMac, well after the meal, I remember those spaces, places, and faces of a younger Vancouver. It was a quiet postwar and post-colonial town, host of the British Empire games, a staid place where you could hear yourself think and, most nights, hear the the Nine O’Clock Gun. A strong residual collective innocence imbued the town like a fine, warm mist. It allowed people to struggle with an egalitarian dignity so that sharing their time and their life was done without question or arid hesitation. In fact, sharing was an unwritten oath of our citizens and community, before TV and the collective conceits that it marketed.

I can’t forget the Italians I’ve met and loved, both as little kid and a young man. They worked, cooked, and ate alongside us day by day, slugging it out like all working class people. I can still smell that first tomato from Papa Paolo and taste that first rigatoni casserole made by Kay DiCastri. Food — the need and the love of it — sustained us all especially when we shared our simple abundance.

MWAHHH!

*

“My Private Italy” is the second in a series of memoir-as-social-history pieces of personal literary work by Grahame Ware entitled In the Moonshadows of My iMac. The first, “My Private Chinatown,” was published in the Ormsby Review #501 (March 08th, 2019). Using a form that is both essay and recollection, Ware fuses the two in the manner of a non-fiction short story. Ware has published feature articles in a wide array of magazines and journals throughout the world. He is currently a book reviewer for Vancouver-based Ormsby Review. When not writing he is carving driftwood sculpture on Gabriola Island, using its natural forms. More info can be had at www.phantasma.ca

*

The Ormsby Review. More Books. More Reviews. More Often.

Editor/Designer/Writer: Richard Mackie

Publisher/Writer: Alan Twigg

The Ormsby Review is a journal service for serious coverage of B.C. books and authors, hosted by Simon Fraser University. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Robin Fisher, Cole Harris, Wade Davis, Hugh Johnston, Patricia Roy, David Stouck, and Graeme Wynn. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. As of September, 2018, Provincial Government Patron: Creative BC

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

East Vancouver looking west, 1962, with the Hastings Park complex in foreground. Empire Stadium at bottom, PNE (Pacific National Exhibition) Fairgrounds above, Hastings Park Race Track at right, downtown Vancouver and Stanley Park in the distance. George Allen photo. Vancouver Archives

Leave a Reply