#184 Margaret Ormsby remembered

October 18th, 2017

Just over a year ago, in “Welcome to the Ormsby Review” (September 16, 2016), Richard Mackie provided his memories of Margaret Ormsby, the B.C. historian after whom The Ormsby Review is named. Mostly these referenced his conversations in two fine, old living rooms in the Coldstream Valley, near Vernon, where she lived; on Chintz-covered sofas and comfortable armchairs at her house called Garafine, and at Lake House, his cousin Paddy Mackie’s house nearby. Mackie concluded, “Twenty years after her death, The Ormsby Review gives us a chance to continue our conversations about British Columbia.” Responses to that article have been considerable, prompting this forum for the opinions and memories of others. – Ed.

*

Margaret Ormsby: catalyst & mentor

by Richard Mackie

My own recollections of Margaret, all from the 1980s and 1990s, prompted more of a conversation than I expected.

Some twenty readers of The Ormsby Review emailed me and or left unsolicited comments. Their memories and photographs span a century. Their much-appreciated recollections can be divided into the main phases of her life:

- Parents and childhood.

Ormsby Review contributor Mike Sasges of Merritt drew my attention to the Ormsby family documents and photographs at the Canadian War Museum in Ottawa. Sasges informs us that George Ormsby’s medical certificate for the 30th Regiment, B.C. Horse, dated August 1914, indicates that Margaret Ormsby’s Anglo-Irish father was among the first volunteers to enlist in the Great War. Born in Ireland, Ormsby was thirty in 1914, an Anglican, and a resident of Lumby, a village fifteen miles east of Vernon.[1]

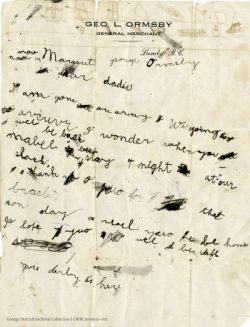

The War Museum has a poignant letter from young Margaret – born 1909 – to her father in the Canadian Army. Dated 1914 or 1915, it is written on her father’s letterhead, Geo. L. Ormsby General Merchant Lumby, B.C. She thanks him for a bracelet he had sent her. Her father must have kept her letter folded together with his medical certificate on the Western front. The two documents show the same crease lines.

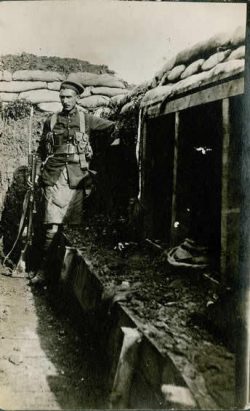

The War Museum also has a photograph of George Ormsby in the trenches in about 1915. The accompanying text reads:

George Ormsby of the 15th Battalion holds a Lee Enfield rifle and wears a kilt cover over his Highland uniform.

This photograph was taken with Ormsby’s own camera, sent to him by his wife.

It was illegal for soldiers to have cameras because of the fear that photographs could fall into enemy hands.

The lack of a helmet indicates it was probably taken before the spring of 1916.

Meanwhile, a sour note intruded. I heard from a former colleague of Ormsby’s from the UBC history department in the 1970s. “She liked to intimate that her family had links with the distressed Irish gentry,” he said, “then I found out that her father was a grocer in Marpole and then Enderby.”

But there is no reason why even a member of the distressed Irish gentry should not work as a grocer — or even in his actual occupation of hardware merchant.

Mike Sasges also sent a photo from the War Museum of George and Maggie Ormsby and their children Margaret and Hugh in about 1919. The accompanying text reads:

As indicated by the wound stripe on his uniform, this photograph was taken some time after 1918, following the completion of Ormsby’s service.

Ormsby served with the 15th Battalion for more than a year before being wounded by shrapnel during the Battle of the Somme in 1916.

A second daughter, Catherine, was born after this photograph was taken. The family developed a fruit farm near Vernon, British Columbia, in the Okanagan Valley on land purchased through the Soldiers’ Settlement Act.

More details of Margaret’s young life came from Howard Hisdal, chair of the history department at Okanagan College in Kelowna:

I read Margaret Ormsby’s book, British Columbia: A History several decades ago and found it fascinating. I found some photographs of her in the Vernon archives and use one of her as a May Day princess in 1921 in my lecture on the history of Camp Vernon…. There were two photographs for two consecutive years. She was princess twice but never queen.

Hisdal continues:

George Ormsby briefly joined my regiment, the B.C. Horse as it was then called, in August 1914 but attested for overseas service on November 10, 1914 with a different regiment. He must have been eager for action and willing to go as an infantryman.

As an older soldier he moved ahead rapidly to the rank of sergeant. It is quite normal to push ahead mature men into the senior non-commissioned officer ranks, especially in high casualty conditions.

Sgt. George Lewis Ormsby served for eighteen months in the trenches, was gassed twice, and wounded by shrapnel on September 26, 1916. That would have been in the later stages of the Battle of the Somme, when the Canadian Corps was sent in. The 15th Battalion took part in an attack on Thiepval Ridge that day just west of Courcelette.

Orsmby healed somewhat from the shrapnel wound, but was no longer fit to carry a pack. While recovering in hospital in England he developed chronic bronchitis and was invalided home to British Columbia in 1917 and eventually discharged on February 21, 1918. That is probably near the date of the photograph judging by the size of the young Margaret. He was in Canada in June 1917 so it could have been earlier.

I was able to access Sgt. Ormsby’s complete military file from the database on the Library and Archives of Canada website. If you want to see his file access the database and type in “Ormsby.” He is the third one listed.

2. Personality as a colleague.

One former colleague of Margaret’s at the UBC history department was not impressed by her as a co-worker, as a person, or as a professional historian.

“I was surprised to see that Margaret Ormsby is being honoured with a publication using her name,” wrote the same person who disparaged her father’s occupation and background. “She was a tricky person to deal with, blowing hot and cold, and with a proprietary view of B.C. history. In the 1970s she reminded me of Queen Victoria in her later days.”

He gives some idea of what Margaret was up against and how pleased she must have been to retire to her comfortable family home. In my own experience, the “proprietary view” accusation is usually levelled at someone whose main crime is possessing a superior knowledge of some topic.

A more public-spirited endorsement came from John Bosher:

A more public-spirited endorsement came from John Bosher:

Congratulations on your initiative in launching the Ormsby Review! As Margaret Ormsby was a colleague of mine, and head of the department of history at UBC when I was teaching there many years ago, I find this project very interesting. Margaret would no doubt be delighted to be remembered. I will be glad to assist in any way I can, certainly by reviewing any books you may care to send along.

Another historian and Ormsby reviewer, Ian Kennedy of Comox, informed me that his friend, the editor Gordon Elliott, had “worked on her British Columbia: A History and on the Centennial Anthology in the years leading up to 1958 when they were published.”

Legal historian Hamar Foster, retired from the University of Victoria, also remembered Margaret. “I had to deal with Ormsby in 1967 when I was Prof. George Shelton’s research assistant for a book he was editing, British Columbia and Confederation. She was quite formidable.”

Margaret has recently been recognized as one of the first women to hold a permanent job in a history department at a Canadian university – at McMaster University in 1940.

Nancy Janovicek of the University of Calgary relayed a shocking anecdote. “I did not meet Dr. Ormsby,” Nancy wrote, “but always tell my women’s history classes that her first office was a desk in the women’s washroom. I’m pretty sure it’s in Creating Historical Memory — probably in the introduction.”[2]

I consulted Dr Google for the origins of this appalling story. A search for “Margaret Ormsby history washroom” will yield half a dozen recent published references to the washroom story. As the story spreads, it has changed slightly; sometimes she was given a desk, sometimes merely a table in that washroom at McMaster.

The source of the story is an article by Alison Prentice in Journal of the Canadian Historical Association in 1991. Prentice, now retired to Victoria, based it interviews at Ormsby’s home on Kalamalka Lake in June 1990:

“Women faculty were thought of as difficult,” Margaret Ormsby admitted. “But,” she added, “a woman had to be difficult in order to survive.” This academic’s first working space, when she managed to obtain a job in a Canadian university in 1940, was a table in the ladies’ washroom. The head of her department apologized that the department “had no offices for women faculty.”[3]

For her 1996 obituary of Ormsby, B.C. historian Jean Barman added that she “considered the only place where men and women were truly equal to be the UBC faculty club dining room.”[4]

3. Impact on students.

The greatest number of correspondents wrote with their recollections as her student. “Your recollections of visits to that fountain of learning and wisdom are wonderful,” reflected historian Barry Gough of Victoria. “I, too, have pleasant memories of this famed historian, especially from being in her History 426 Modern Canada class, arguably the finest undergraduate course on the History syllabus at UBC.”

Surrey historian Mary Carlisle agreed. “By the way, I had the good fortune of taking Margaret Ormsby’s course (1960-61), although I was too young to appreciate it,” she wrote. “I do remember her as a very knowledgeable person and she always dressed well, a pleasant change from the former Oxford types who just threw an academic gown over their rumpled suits before a class.”

Historian Michael Hadley also had gracious memories. “First of all, congratulations on your initiative in launching The Ormsby Review. Margaret Ormsby was a formidable character when I was an undergraduate at UBC in the early 50s, though I passed only briefly through her department.”

Others provided only quick responses. “Great interview with Margaret,” commented the antiquarian and rare book seller David Ellis of Vancouver. “I had her for a prof in Arts 1.” “I was a student of Margaret Ormsby while at UBC,” wrote Ian Kennedy of Comox. And John Bartlett of Princeton lamented that he just missed her: “My first year in Honours History was the year Margaret Ormsby retired – my loss.”

4. Impact on scholarship.

Ormsby’s influence was felt at the provincial level through her magisterial British Columbia: A History (Macmillan, 1958) and in the Okanagan and Similkameen valleys through her local histories and articles.

“I still have copies of her big B.C. book,” wrote book dealer David Ellis. “Rarely requested now, unfortunately.” Brian McDaniel, a lawyer in Duncan, recalled that “Margaret Ormsby’s British Columbia: A History was the first book in my collection which now numbers in the hundreds. I even remember my Dad getting it in Ocean Falls during the centennial year when I was ten. I am sure it is authoritative, but Bowering and Barman are much better reads.”

“I still have copies of her big B.C. book,” wrote book dealer David Ellis. “Rarely requested now, unfortunately.” Brian McDaniel, a lawyer in Duncan, recalled that “Margaret Ormsby’s British Columbia: A History was the first book in my collection which now numbers in the hundreds. I even remember my Dad getting it in Ocean Falls during the centennial year when I was ten. I am sure it is authoritative, but Bowering and Barman are much better reads.”

Michael Hadley added that, “In later years I read her British Columbia: A History with great pleasure. I would have had little sympathy with the ‘quantifier’ at UVic who dismissed it.”

When my own family moved in 1968 to B.C. from Edmonton, my parents were given Ormsby’s book as a welcoming present. They lent it to me in 1981 and I have never returned it!

John Bartlett reminded me of the value of Ormsby’s local work. “Her early work with the Okanagan History Society is still of great value… Best wishes to all associated with this new project.”

Barry Gough reminded me that her colleagues and students did, in fact, honour her contribution shortly after her retirement in 1974.

“A festschrift was published for her,” Gough wrote, “a testament to the esteem held by her many fellow historians. I was pleased to be included. The Ormsby Review will continue the legacy, and thank you for launching it.”

Unexpectedly, I heard from literary biographer David Stouck, whose teaching assistant in the English Department at SFU was Margaret’s younger sister Catherine. “Cathy Marcellus was the name of Margaret’s sister,” he wrote. “Cathy was very proud of Margaret, but turned out — as a senior citizen — to be quite a good scholar herself. She was an excellent teaching assistant, for example.”

5. In retirement

When I knew her, in the 1980s and 1990s, I had no idea that so many of her ex-students and colleagues made regular pilgrimages to Garafine, her house on Kalamalka Lake near Vernon. She was far from stranded or isolated at her lakeside house and orchard in B.C.’s interior, and I was not the only one to make the trek.

Historian Keith Ralson and his wife Molly, and sometimes their son — now Hon. Bruce Ralston, MLA — visited regularly. Keith, a respected labour historian, had been a student researcher along with Gordon Elliott on British Columbia: A History.

Another visitor was Alison Prentice, who learned the McMaster washroom story. Patricia Roy, Barry Gough, and Cole Harris also dropped in to see her. I introduced some of own contemporaries to her, including Daniel Clayton and Daniel Marshall.

“I visited her and drank sherry in her home in Vernon with my editor and friend Gordon Elliott when we were touring BC ‘researching’ our Pub Book,” wrote Ian Kennedy.

Art historian Martin Segger of the University of Victoria also got to know her in the 1980s and passed on these stories:

I served for some years on the British Columbia Heritage Advisory Board, as a cross appointment from the Board of the B.C. Heritage Trust. Margaret was a member of the former. Both boards made an effort to meet in locations around the Province. On a couple of occasions while meeting in the Okanagan we dropped by for tea. She was a great host and raconteur.

However, one of my best memories was a meeting in Prince George. We went out to visit the alleged original (archaeological) site of Fort George. This required a river trip in an open boat, from which we had to wade ashore. Margaret wasn’t too keen on that so two volunteers jointly hoisted her on their shoulders to make the ship-to-shore transfer. We were all greatly amused, but no one more so than her!

Naval historian Michael Hadley emerged from the undergraduate anonymity of UBC to meet her at last. “I had the pleasure of meeting her personally only once — at a reception for Fellows of the Royal Society of Canada at the University of Victoria. I recall our conversation over a glass with great fondness, and wish I had known her earlier.”

But not all recollections were so positive. My cousin Paddy, who cordially introduced me to Margaret in the mid 1980s, in private was less polite. He felt she had a proprietorial attitude to Coldstream history. He found her Coldstream: Nulli Secundus (Friesen, 1990) dull. He thought she had relied too much on the dry documentary record and not enough on local historians and old-timers like himself with their vast and lively store of anecdotes, genealogical connections, tittle-tattle, and scuttlebutt. She was too much of a professional historian for his liking.

But not all recollections were so positive. My cousin Paddy, who cordially introduced me to Margaret in the mid 1980s, in private was less polite. He felt she had a proprietorial attitude to Coldstream history. He found her Coldstream: Nulli Secundus (Friesen, 1990) dull. He thought she had relied too much on the dry documentary record and not enough on local historians and old-timers like himself with their vast and lively store of anecdotes, genealogical connections, tittle-tattle, and scuttlebutt. She was too much of a professional historian for his liking.

He retaliated by gossiping about her. He told me several times with considerable relish that Margaret’s father, George Ormsby, had been “blackballed” for membership in the orchardists’ and ranchers’ Kalamalka Club because, as a hardware merchant, he was “in trade.”

So much for the integrity and contribution of a married man with two children, wounded at the Battle of the Somme.

This all came back to me when Paddy’s friend Frances Hill of Grindrod dropped me a line. “I met Margaret Ormsby once when Paddy gave a tea for her. I have never in my life met a more totally boring person. Of course, Paddy being always the complete gentleman never let on that he felt the same. We talked about it afterwards.”

Finally, lawyer Joe Simpson of Duncan responded to my anecdote that Margaret Ormsby served hot buttered toast to visitors at Garafine for tea at 4 p.m. with a memory based on Kenneth Grahame’s classic The Wind in the Willows (1908):

I’ve enjoyed dipping into the ongoing stream of Ormsby reviews etc & also enjoyed your own contribution to the latest BC Bookworld. Your passing reference there to buttered toast suddenly transported me back to my early days in N. Ireland when our primary school class, aged around eight yrs, was assigned as reading material the book Toad of Toad Hall, and 56 years later I still can recall with some considerable relish Toad’s musings about the delights of hot buttered toast. If memory serves me right, poor Toad was temporarily imprisoned at the time, and such small luxuries were denied him. Such literary poignancy!

*

All these messages indicate that the conversation initiated by Margaret on her veranda and living room above Kalamalka Lake has continued.

The fragments and anecdotes still arrive. As Alice Munro wrote, “We can’t resist this rifling around in the past, sifting the untrustworthy evidence, linking any stray names and questionable dates and anecdotes together, hanging onto threads, insisting on being joined to dead people and therefore to life” (The View from Castle Rock, 2006).

But instead of just two people talking and sharing stories, the conversation now involves hundreds of contributors and thousands of readers. Some 200 people have provided essays, book reviews, and books to this online journal named for a great communicator about British Columbia.

[1] http://www.warmuseum.ca/firstworldwar/wp-content/mcme-uploads/2014/08/e-20000013-002.jpg

[2] Beverly Boutilier and Alison Prentice, editors, Creating Historical Memory: English-Canadian Women and the Work of History (Vancouver: UBC Press, 1997).

[3] Alison Prentice, “Bluestockings, Feminists, or Women Workers? A Preliminary Look at Women’s Early Employment at the University of Toronto,” Journal of the Canadian Historical Association (1991), pp. 231-258. The washroom quote is at p. 258.

[4] Jean Barman, “Margaret Ormsby, 1909-1996: Doyenne of BC history,” UBC Reports 42: 19 (November 14, 1996), p. 5.

*

Richard Somerset Mackie has twice won the province’s top honour for historical writing about British Columbia, once for his book on early fur trading and again for his study of logging on Vancouver Island. His classic Vancouver Island study Island Timber, went through five printings and has sold 10,000 copies. From 2011 to 2016, Mackie was associate editor and book reviews editor at the UBC-based academic journal BC Studies, greatly enhancing its vitality and appeal. In September of 2016, he accepted a new position as editor for The Ormsby Review. He worked in BC archaeology between 1976 and 1984, then studied mediaeval history at the University of St Andrews and history and historical geography at the universities of Victoria and British Columbia, where he obtained a Ph.D in 1993.” Richard Mackie’s Mountain Timber: The Comox Logging Company in the Vancouver Island Mountains (Sono Nis 2009) is the sequel to Island Timber, concerned with Comox Logging’s later and higher fortunes in the densely-forested valleys and lakes of the Vancouver Island mountains. For Home Truths: Highlights from BC History, Mackie and Graeme Wynn, assembled an anthology of articles drawn from BC Studies (1968 -2012).

*

The Ormsby Review. More Readers. More Reviews. More Often.

Reviews Editor: Richard Mackie

Reviews Publisher: Alan Twigg — BC BookWorld / ABCBookWorld / BCBookLook / BC BookAwards / The Literary Map of B.C. / The Ormsby Review

The Ormsby Review is a new journal for serious coverage of B.C. literature and other arts. It is hosted by Simon Fraser University. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Robin Fisher, Cole Harris, Wade Davis, Hugh Johnston, Patricia Roy, David Stouck, and Graeme Wynn.

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

Thank you for this. I have her British Columbia: A History on my desk and use it several times a week. I love her perspective. It is of her time and of course that should be kept in mind. Each generation has its own interpretation(s) of events and its own way(s)of commemorating those but surely we always need the solid work of the past to build on and renew, again and again. I don’t think she ever expected to be the final word. She doesn’t write as though she expected that. Her work anticipates Jean Barman and Barry Gough and the current scholars. The silences regarding Indigenous histories need to be addressed and amended but hers is a wonderful passage in the running story of our place.

Wise words, Theresa. Ormsby’s history of British Columbia is a great synthesis and a big achievement for any era, especially the 1950s, when the B.C. historical community consisted of how many active scholars? Somewhere between five and ten? And when a scholar’s tools were archival immersion, file cards, foolscap, pencil first drafts, and infinite patience. From my talks with her I know that she had a tenacious belief in the worth of this book. I also use British Columbia: A History as a reference book, especially for political events. It is accurate and reliable and its “periodization” still holds.