Lock ’em up, lock ’em up, lock ’em up

The racist tactics of Conservative Premier William Bowser (1915-1916) are unearthed in an Ormsby exclusive.

October 17th, 2017

Fernie's place on this map has finally been given proper scrutiny by historian Wayne Norton.

The internment camps at Fernie and nearby Morrissey were dress rehearsals for the removal of Japanese Canadians from the B.C. coast in 1942.

[The new book by one of B.C.’s most integral historians, Wayne Norton, is Fernie at War 1914-1919 (Caitlin $24.95) in which describes what life was like in that small Kootenay town when its citizens optimistically supported Britain, only to suffer staggering losses amid controversies that decimated the town’s spirit. 978-1-987915-49-5]

Refuge of a Scoundrel: Patriotism and William Bowser

by Wayne Norton

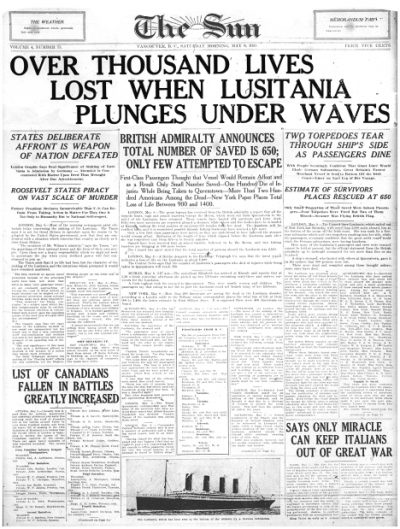

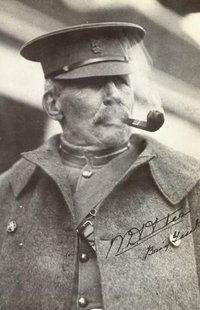

In this Ormsby Review exclusive, Wayne Norton reveals that in his brief term in office (1915-16), the Conservative Premier William Bowser fanned the flames of patriotism stoked by mounting Canadian war casualties and the German sinking of the passenger liner Lusitania off the Irish coast in May 1915.

Bowser engineered the imprisonment of miners and other local settlers of German, Austrian, Ukrainian, Bohemian, and “Teutonic” and Slavic descent generally in the East Kootenay. He and others saw these men — mostly recent immigrants — as a security threat and as a menace to the employment of British subjects in the coalmines around Fernie.

Bowser’s internment policy, with its dubious legal basis, provoked a labour crisis in the mines as the war absorbed local manpower. By September 1916, most miners of military age had either enlisted or had been interned. Bowser, Norton concludes, has “not yet been held accountable for the social strife and the near economic disaster he caused in Fernie.”

Norton also notes that this episode “has been completely overshadowed by the experience of Japanese residents of this province during the Second World War.” First World War internments like those at Fernie and nearby Morrissey were dress rehearsals for the removal of Japanese Canadians from the B.C. coast in 1942 and their incarceration in temporary camps throughout the interior. – Ed.

*

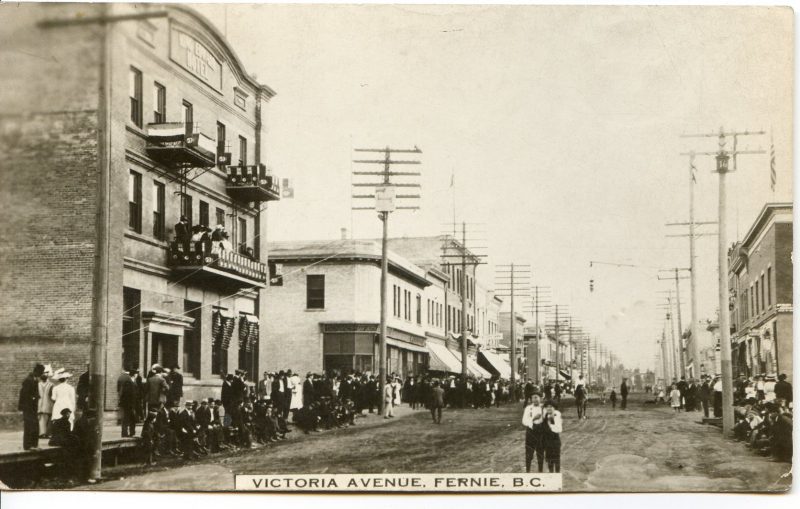

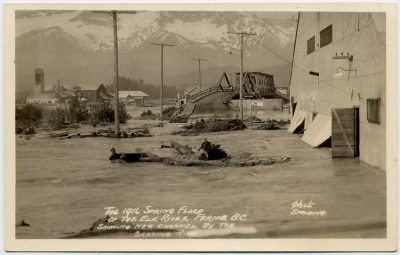

By any measure, Fernie is a long way from Victoria. Geographically, the small city is tucked away in the south-eastern corner of the province; politically, it is often out of step with opinion at the Coast and in the rest of the Interior; economically, when its fortunes were primarily dependent on coal, its orientation was to the east and south, and today — with an economy based primarily on tourism — that orientation still prevails.

Consequently, Fernie is often seen from Victoria not only as distant but also as marginal and insignificant. Yet a century ago, it was in Fernie where an ambitious provincial politician took a calculated risk that was responsible for perhaps the most dramatic episode in British Columbia’s domestic wartime history.

Curiously, that episode has been completely overshadowed by the experience of Japanese residents of this province during the Second World War, while the politician has not yet been held accountable for the social strife and the near economic disaster he caused in Fernie.

With the outbreak of war in Europe in August 1914, British Columbia’s provincial government immediately indicated it was keen to become involved in matters of domestic security. Premier McBride famously purchased his two submarines for coastal defence and welcomed a federal request for assistance in dealing with resident national subjects of Germany and Austria-Hungary, individuals newly designated as enemy aliens.

McBride responded to that request by offering provincial premises at Nanaimo and Vernon for internment purposes. Victoria architect William Ridgeway Wilson, an officer with the militia unit in Esquimalt, was quickly appointed as head of the new and grandly named Department of Alien Reservists. The British Columbia Provincial Police, with authorisation from A.P. Sherwood, Chief Commissioner of Police in Ottawa, became responsible for administering the oaths of loyalty required by new federal regulations from enemy aliens. By month’s end, it was clear that politicians, military officials and police in British Columbia were prepared to play a significant role in protecting citizens from any perceived wartime threat to safety and security.

During Premier Richard McBride’s prolonged absence in England, Attorney General William Bowser assumed the role of acting premier. His Conservative party enjoyed overwhelming control of the Legislature, but Bowser was presiding over a government increasingly divided and unpopular as a deep economic depression continued to take its toll. Anticipating a general election but struggling to cope with the effects of the depressed economy, Bowser was attempting to regain popularity for provincial Conservatives through legislation and policies intended to attract the support of working-class voters.

The boom years that ended abruptly in 1912 seemed a distant memory. A stubbornly high level of unemployment prevailed throughout the province. Men out of work typically migrated to the larger centres in search of broader opportunities. During the winter of 1914-15, the civic governments of Vancouver and Victoria were providing relief work for some, but were complaining about having to sustain nationals of Germany and Austria-Hungary. The city of Nanaimo too was struggling with the near exhaustion of its available relief funds and civic financial credit.[1]

In the minds of many, the war, foreign nationals — typically migrant workers from Italy, western Russia and the eastern stretches of Austria-Hungary — unemployment and internment were inextricably linked. Under the federal War Measures Act, the internment camps at Vernon and Nanaimo were opened in September 1914 to confine enemy aliens considered threats to national security, but influential voices were calling for the internment of everyone born in Germany and Austria-Hungary — whether single or married, whether naturalised or not.

The most politically powerful of those voices belonged to acting premier William Bowser. Constitutionally, the power to deal with foreign nationals belonged solely to Prime Minister Borden and the federal government. Bowser was well aware of that. To relieve both unemployment and the pressure on civic relief funds in British Columbia, he urged federal authorities to use that power to deport unemployed foreigners and to intern enemy aliens.

Borden did not act on the demand for deportation, but he did finally agree in late April 1915 that unemployed enemy aliens in British Columbia could be interned. On Bowser’s orders, the Provincial Police immediately began to make arrests in Vancouver and Victoria as well as in the central Interior, where dozens of migrant workers were waiting hopefully for railway construction to resume.

The arrests attracted widespread approval for Bowser and his Conservatives. City governments in Vancouver and Victoria were pleased for economic reasons, but more significantly, the general population applauded the action as patriotic. As the arrests were proceeding, news of the sinking of the Lusitania in early May resulted in a further surge of anti-German feeling. Two days of rioting in Victoria were ended only by a declared state of emergency and martial law.

The Vancouver Sun newspaper intensified the agitation for the internment of all enemy aliens and a number of Lower Mainland organisations — including Vancouver’s Rotary Club and Board of Trade — echoed that demand. So too did the civic governments of Vancouver, South Vancouver, and North Vancouver, the latter also demanding the deportation of naturalised German-born and Austro-Hungarian-born British subjects “who through their acts appear to be unfriendly to the allies.”[2]

The Daily Colonist editorially joined the chorus for interment, while in Nanaimo a brief strike of miners at the Western Fuel Company unsuccessfully demanded the dismissal of all Austro-Hungarians working with them. It was abundantly clear, with respect to matters of internment, that Bowser was not out of step with public opinion; he was acting in concert with it.

Although it was certainly shared, the outrage occasioned by news of the sinking of the Lusitania in early May did not find the same extreme expression in Fernie as it did at the Coast. The Fernie Free Press condemned the German action against the Lusitania, but did not link it to the issue of internment. And unlike its coastal counterparts, the city council did not consider a resolution demanding the broadening of internment policies. No attempt to arrest enemy aliens simply because they were unemployed was made by Provincial Police in East Kootenay. Although there was no shortage of patriotic opinion in Fernie, there was no sense it could find violent expression.

That sense of calm did not prevail at the Coast. By the middle of May, more than 300 prisoners were being transferred to the custody to Internment Operations.[3] One Victoria newspaper reported that the arrests in the capital had been made because of too much celebration over the sinking of the Lusitania. In fact, they were simply part of the policy of interning unemployed enemy aliens. Ironically, for all the intensity of anti-German outrage, very few of the prisoners were German nationals. Overwhelmingly, they were migrant workers of various ethnic origins from the Austro-Hungarian Empire.

That intensification of patriotic feeling led Bowser to contemplate a larger move. The most significant impediment to his hopes for attracting the working-class vote was the deep animosity he had personally earned by ordering the militia to intervene during the bitter Vancouver Island coal strike of 1912-14. Even a year after the strike’s conclusion, due to a combination of depressed coal markets and blacklisting of those who had participated in the strike, unemployment was high in Nanaimo and the other Island mining communities.

The policy of interning unemployed enemy aliens did nothing to address this situation in Nanaimo-area coalmines because the unemployed were not enemy aliens. They were typically British-born and Canadian miners. With all that in mind, Bowser turned his attention to employed enemy aliens. The long anticipated entry of Italy into the war on the side of Britain and France on 23 May removed one significant obstacle to his plans as the wartime status of Italian-born residents was finally clarified.

With evident pride, Bowser announced on 25 May in Victoria that the federal Minister of Justice had approved his proposal to inter enemy-alien miners working in the Vancouver Island coalfield at Nanaimo, Ladysmith, South Wellington, and Cumberland. He was quick to add that overcoming the hesitation of federal officials had taken much effort on his part. In addition to having the appearance of a patriotic action responsive to demands for internment of enemy aliens, the initiative was calculated to ease Nanaimo’s financial burden by creating employment opportunities for still unemployed British miners, while, at the same time, easing the resentment those miners felt toward him personally and against the foreigners who had taken their places during the strike. As a political calculation seen from Bowser’s perspective, it seemed to have no downside whatsoever.

One of the concerns expressed by federal authorities was that the small internment camp at Nanaimo and the much larger one at Vernon were already near capacity. Bowser persuaded them that the new Saanich Prison Farm near Victoria easily possessed sufficient capacity to accommodate the prisoners until Internment Operations was able to accept them. He spoke of removing the menace to the community that enemy aliens represented and pointed to the advantage his policy afforded to “white workingmen on Vancouver Island.”[4]

Even as Bowser was making his announcement, military officials were arriving in Nanaimo to implement the plan. Major Ridgeway Wilson, having received federal endorsement of his authority to oversee internment matters in British Columbia, was responsible for supervising the operation.

Orders were received by Provincial Police in Ladysmith and Nanaimo to identify all miners of enemy alien origin. Within 48 hours came the subsequent order to arrest them.[5] On 28 May, 64 prisoners from Nanaimo and Extension were sent aboard the Princess Patricia to Vancouver en route to the internment camp at Vernon; three dozen more were escorted aboard the south-bound Esquimalt & Nanaimo train bound for the Saanich Prison Farm, with an additional fourteen prisoners added to their number at Ladysmith.[6]

The entire operation was carried out smoothly and successfully. Bowser personally wrote to mine managers urging them to hire unemployed British miners to fill positions vacated by the internees. He then sent a provincial relief officer to Nanaimo to encourage them to follow that advice.[7] Instructions were soon issued to Provincial Police to enumerate all enemy-alien miners at Cumberland. On 3 June, 33 employees of the Union Colliery Company were handed over by Provincial Police to military authorities at Union Bay.[8]

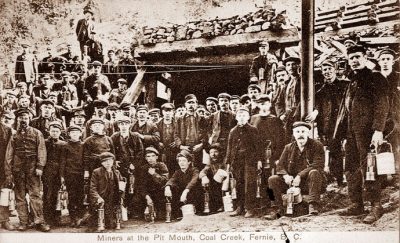

Having achieved such a remarkable success on Vancouver Island, it was only logical that the same policy should be applied to the province’s other coalfield. That coalfield was located in East Kootenay and was home to two companies: the Crow’s Nest Pass Coal Company (CNPCC) — with headquarters in Fernie — employed approximately 1600 men at its Coal Creek and Michel mines; the workforce of the much smaller and more isolated Corbin Coal and Coke Company numbered perhaps one hundred.

Provincial Police constables at Coal Creek and Michel soon received the same order as that given to their counterparts at Nanaimo, Ladysmith and Cumberland. On 6 June, Constable Boardman at Coal Creek spent the day gathering all particulars of enemy-alien miners, including place of birth and marital status; similarly, Constable English at Michel spent that day and the next notifying those identified as enemy aliens to make preparations to report to the police station.[9]

Although all seemed to be following the pattern established by the arrests on Vancouver Island, events in East Kootenay very quickly spun out of Bowser’s control. While Fernie was an isolated community in 1915, its residents were well aware of developments on Vancouver Island and its coal miners were anxious to benefit from the same opportunities for increased employment. The economic depression had hit the East Kootenay mines hard and, despite frequent predictions of imminent improvement, miners at Coal Creek on average were working just two shifts per week. The outrage occasioned by the Lusitania affair had increased patriotic feeling sharply, but even that had resulted in no action like the riot in Victoria or the brief and unsuccessful strike by miners at the Western Fuel Company in Nanaimo. However, Bowser’s internment initiative in the Vancouver Island coalfield proved to be the game-changer that quickly led to an ugly demonstration of anti-foreigner sentiment in Fernie.

Although much reduced because of the economic depression, the number of men employed by the CNPCC remained surprisingly high. The company declared 1,280 employees were engaged in its coal and coke operations at Fernie and Coal Creek in June 1915. Approximately half were English-speaking, a largely British immigrant community that dominated the skilled job categories. Also in skilled positions were a few dozen Belgian and French miners, emigrants from the coal districts straddling the Belgian-French border.

The CNPCC further confirmed that it also employed there — typically as unskilled labourer — nearly 300 Italians, 90 Russians, 165 Austro-Hungarians and 25 Germans. Differing somewhat, newspapers reported approximately 1,100 men engaged in the mines and at the coke ovens, with an Austro-Hungarian figure of only 125.[10] Whatever the actual numbers were, apart from a few unskilled labourers at the coke ovens in Fernie and nearly four dozen pit bosses, fire bosses, clerks and salaried officials, they were all members of the Gladstone local of the United Mine Workers of America (UMWA) — the largest and most influential local union in District 18.

Labour peace had long prevailed at the Coal Creek mines, with not a single day lost to job action since 1911. Miners accepted that grievances should be dealt with through channels sanctioned by their contract, and those seeking an Island-style purge of their fellow workers from Germany and Austria-Hungary would necessarily have looked to their union leaders to make the case to company officials.

Although Fernie was home to both local and district union leaders, not one of them endorsed such a course of action. Principles of union solidarity were firmly held by the union leadership and District 18 was formally allied to the Socialist Party of Canada, which emphasised those same principles. One observer soon noted that “a bad feeling” prevailed for several days amongst English-speaking and Italian miners.[11] That the bad feeling almost certainly resulted from a refusal by District 18 and Gladstone local union leaders to endorse the position being demanded by the membership.

On Saturday, 5 June, the superintendent of the Coal Creek mines, Bernard Caufield, was visited by a delegation of eight drivers — five of them Belgian, three of them English-speaking — who, citing safety concerns, told him they were opposed to working underground with enemy aliens. Caufield told them that such an issue could only be discussed through union channels and it was clear the drivers were acting on their own.

On the following Monday, 7 June, during the course of the day’s work, British, Italian, Belgian and Russian employees reached a consensus to back the drivers’ position. It is not clear if the miners knew of visits made by Constable Boardman to enemy-alien employees living in Coal Creek the day previous. If they did, they were either very impatient or more likely not aware that those visits signalled the imminent order from Victoria that would deliver precisely what they desired.

On Tuesday, 8 June, miners scheduled for the morning shift at Coal Creek donned their clothes at the washhouse as usual and took out their lamps as usual, but only the fire and pit bosses and just a few others reported for work. Most of the men remained at the washhouse where they resisted all attempts to persuade them to begin their shift. Their local union secretary, Thomas Uphill (who had also recently been elected mayor of Fernie) reminded them of the penalty clause in their recently signed collective agreement that would see each man fined a dollar a day for an illegal strike. Bernard Caufield told the men the company was operating at a loss and work stoppages could only deepen that loss, thereby threatening their jobs. But the men were adamant — they would not work until enemy aliens were no longer working with them. Caulfield quickly realised he had no option but to declare the day idle.

An emergency meeting was called for 2:30 that afternoon in Fernie. Convened in the Socialist Hall, the gathering was quickly moved into an open space outside when the hall proved much too small to accommodate the surprisingly large crowd of approximately 600. District 18 President William Phillips and UMWA International board member David Rees (both residents of Fernie) were present, as was Thomas Uphill who agreed to chair the meeting.

During the course of the next two hours, as many as twenty speakers addressed the assembled miners. Rees and Phillips each stood to argue that the foreign-born had joined in the common struggle against the capitalist class, and having engaged in no misconduct, deserved “British fair play.” Constantly interrupted, neither man held the floor for long.

Options proposed at the meeting included a separate mine for enemy-alien miners, immediate termination of their employment, or internment. Superintendent Caufield stated emphatically that the idea of a separate mine was entirely impractical and insisted the miners were asking the company to perform what was fundamentally the responsibility of the federal government. Uphill briefly surrendered the chair to repeat the arguments of Rees and Phillips, but the assembled miners were steadfast. They selected six delegates to advise the CNPCC officially of the stand being taken and then adjourned to re-convene at the skating rink in the early evening.

When the delegates called upon company officials at the CNPCC administration building, they were told that, with general manager William Ritson Wilson away on a visit to the United States, no formal response could be given and no action taken until he returned. The delegates duly reported back to the reassembled miners at the skating rink, but found them unwilling to wait. The determination of those present was undiminished. After a few references to the Lusitania and to Belgian atrocities, the meeting passed a motion: “We, as Britishers and others, other than aliens, are willing to work and will work, but not under present conditions, that is to say, with alien enemies.”[12]

The clumsy wording caused the two local newspapers to report the resolution differently — by the Fernie Free Press as a refusal to return to work until all enemy aliens had been discharged by the CNPCC; by the UMWA-owned District Ledger as a call to intern all enemy aliens. Whatever its precise wording or intention, the resolution passed easily. The Gladstone local union was on strike for the first time in four years. Maintaining a business-as-usual stance, Caufield posted notices in Fernie and Coal Creek requiring the Wednesday morning shift to report for work as usual.

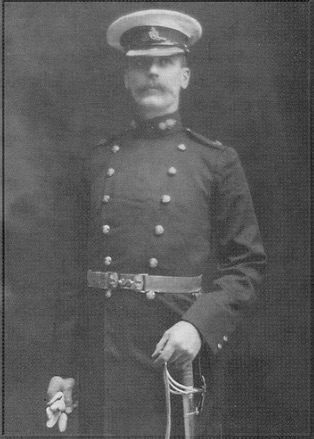

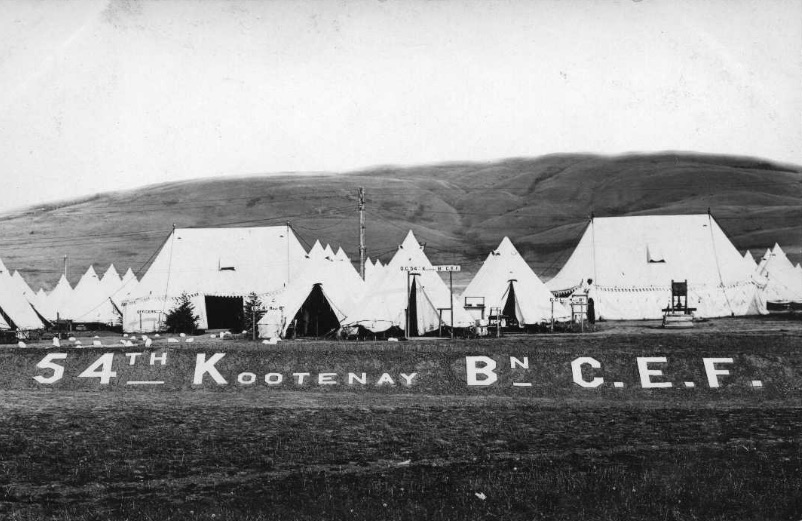

The senior military officer in Fernie, Lieutenant-Colonel Joseph Mackay, was busy preparing for the departure of the 54th Kootenay Battalion for training at Camp Vernon. Alarmed but with no authority in matters of internment, he wired his superior in Victoria for instructions on the afternoon of the meeting. A response arrived quickly — but not from military authorities and the instructions were not for Lieutenant-Colonel Mackay. Informed of the miners’ demands, Attorney General and Acting Premier William Bowser wasted no time. While the miners were still meeting, he instructed Colin Campbell, Superintendent of Provincial Police, “to intern all single aliens working in Mines.”

Chief Constable George Welsby at Fernie received his instructions from Campbell in sufficient time to have notices printed the same evening. Conflicting with those posted by the CNPCC, they commanded all unmarried and unnaturalised enemy-alien CNPCC employees of military age to report to him in Fernie the next day. He advised Constable Joseph Boardman in Coal Creek to swear in special constables. Internment was to begin Wednesday, 9 June.

For many English-speaking miners, the Austro-Hungarian and German employees of the CNPCC had become the face of the enemy. A good number of these co-workers were known to be reservists in the armies of their homelands; few of them mixed socially outside the workplace. Demanding punitive action against the readily identifiable and socially marginalised local representatives of enemy states could easily be seen as a patriotic responsibility. The leadership of the union — like the general membership, comprised of British immigrants both locally and district-wide — was unanimously opposed to the call to dismiss enemy aliens from employment. But with the strong majority at the meeting determined to prevail, the principles of socialism, union solidarity and equality before the law were easily overwhelmed.

Unaware of Bowser’s plans, the rebellious miners were demanding what was about to be freely offered. The order Welsby received on 8 June cannot have been entirely unexpected. It was simply delivered sooner than planned. The fact that neither Major Ridgeway Wilson nor any other military officials associated with internment were present in Fernie clearly indicates that Bowser had been forced to act before he was ready. CNPCC general manager William Wilson, who just left Fernie for a visit to the United States, must also have known that the broadening of Bowser’s Island internment policy was possible at some point in the future. However, neither he nor anyone on the Board of Directors of the CNPCC had received any indication from Victoria or from Chief Welsby that such an initiative was about to be launched in East Kootenay. Like Joseph MacKay, William Wilson was taken completely unawares by the internment order.

However, the miners’ strike in turn had surprised Bowser. He surely would have preferred more time to prepare logistically for the East Kootenay operation, perhaps dealing first with Coal Creek, later with Michel, and presumably later still with Corbin. But the revolt of 8 June forced him to advance his timetable. The miners’ strike had forced his hand. It had simply become necessary to apply immediately to the East Kootenay coalfields the same policy that had been followed on Vancouver Island. The logic of applying the same policy to Fernie was certainly on his side, but the prospect of a prolonged labour dispute with reminders of his involvement in the recently concluded Vancouver Island coal strike was to be avoided if at all possible. Instead, he chose to respond publicly, patriotically and energetically to the demands of the workingmen whose support he was so assiduously courting.

Only Fernie’s Conservative Association seemed unsurprised. Meeting on the afternoon of 9 June — just as the first internees were being processed at the courthouse — local Conservatives adopted a well-considered proposal to establish a permanent internment camp at an abandoned townsite a few miles to the south. Anticipating up to 400 prisoners from Fernie alone and citing the high costs that would be incurred in transporting them elsewhere, the meeting resolved “to request the proper authorities to make the necessary arrangements to secure the Morrissey Mines townsite as an internment camp for this district.” Both the townsite, which was owned by the CNPCC, and the privately owned buildings within it were still in good condition, having been abandoned just a few years earlier when coal mining ceased there in 1909. The resolution was telegraphed immediately to those in charge of Internment Operations and to Fernie’s Member of Parliament, but the proposal was quickly rejected.

In Victoria on the same day, Bowser said he had the full cooperation of mine managers as well as the sanction of military authorities. In fact, he had the cooperation and sanction of neither. William Wilson would later state unequivocally that he had not been consulted and neither had the company’s governing board.[13] And unlike the Vancouver Island operation — where military officials were arriving in Nanaimo just as Bowser made his announcement in Victoria — no military personnel from Internment Operations were in Fernie. They too apparently had not been informed that an immediate internment of miners was a possibility at Fernie. Echoing his remarks about the internments on Vancouver Island, Bowser stated his purpose at Fernie was to create employment for “deserving men who find themselves out of work.” “Full advantage,” he said, “should be taken of the chance to relieve unemployment,” adding again that his decision was intended to remove a menace to the peace of the community.

It would soon become apparent that his action had introduced a menace to the peace of the community. Because of the greater number of enemy aliens employed by the CNPCC and because no arrangements were in place for accommodating internees, the situation at Fernie was immediately more complicated than that on Vancouver Island. The provincial lock-up at Fernie would clearly not suffice on even a temporary basis. Cells in the basement of the provincial courthouse in Fernie were built to house a maximum of 24 prisoners. Chief Welsby scrambled to make arrangements with the rink manager and with Lieutenant-Colonel Mackay, who was using the property for the military purposes of the 54th Kootenay Battalion. Both agreed to relinquish the skating rink to serve as a temporary jail.[14]

On the morning of 9 June — as local Conservatives prepared to meet and as Bowser spoke to the press in Victoria — Fernie residents affected by the Welsby’s posted order of the previous evening began to report to the Provincial Police office at the courthouse. At three o’clock, they heard the buglers of the 107th East Kootenay Regiment leading the volunteers of the 54th Kootenay Battalion to another in the series of farewell events the community was holding in honour of their imminent departure.

Sometime after four o’clock, the prisoners were joined on the grounds of the Fernie courthouse by 28 unmarried enemy aliens who arrived on the train from Coal Creek, where Constable Boardman and his two special constables had arrested them during the course of the day. Blankets and personal belongings were searched for alcohol and concealed weapons before the men were escorted the short distance down the hill from the courthouse to the skating rink. One hundred and eight men spent their first night as prisoners of the Province of British Columbia.[15]

Following a four-hour meeting on the morning of 10 June, miners agreed to return to work at Coal Creek. Constables in Michel and Natal — where the mines employed a far larger number of Austro-Hungarian workers — attended to the swearing in of special constables, while those based in Corbin, Elko, and Hosmer travelled to Fernie to assist with internment duties. On 10 June, Constable Hughes of Natal and four special constables brought 67 enemy aliens to the skating rink.

On the same day, four Austro-Hungarian prisoners from Cranbrook, probably temporarily destined for the provincial lock-up in Fernie in transit to Lethbridge, found themselves held instead at the day-old internment camp. One of them made the camp’s first escape attempt the following day.[16] Constable English of Michel and his four special constables arrived with 84 prisoners on 11 June; Hughes returned on 12 June with sixteen more. Constable English may well have noticed a large number of Italian reservists practising their military drills as he brought in nineteen more prisoners from Michel on Sunday, 13 June.[17]

As numbers at the skating rink rose rapidly, providing adequate food and facilities became a challenge. The Elk Lumber Company supplied the materials and Trites-Wood the hardware necessary for fencing and for the quick construction of latrines behind the building and for rudimentary kitchen facilities inside. Welsby made arrangements for groceries, meat and bread with a number of local suppliers. Behavioural expectations and other arrangements within the compound also had to be quickly established. Internees found they were required to do their own cooking and cleaning. Three dozen local men — most presumably previously unemployed — were hired as special constables to guard the compound in eight-hour shifts at a rate of $2.50 per day.

On just the camp’s second morning, 11 June, as some prisoners went about assigned tasks and as others contemplated or discussed their new circumstances, they heard cheers and music from Victoria Avenue. A civic holiday had been declared and businesses were closed as what was reported as “practically the entire city” turned out to cheer the departing Fernie contingent of the 54th Kootenay Battalion along their parade route from the recruiting office to the CPR station. They were to leave on the same train that brought the first internees from Michel.

Accompanied by the bugle band and an honour guard of the 107th East Kootenay Regiment, soldiers destined for the battlefields of Europe marched along the city’s main street. At the station, the Italian Band took over musical responsibilities. For the first time, Russian nationals were amongst the volunteers. The men listening from their confinement at the skating rink did not likely share in the sense of celebration.

Both local newspapers reacted to the internment with caution. They reported extensively on the developing situation in their editions at the end of the first week of the process, observing that the prisoners seemed cheerful and philosophical about their situation and were passing the time with card games and music. The Free Press commended the Provincial Police for their handling of the situation and expressed the hope that all parties would “meet the situation with that restraint and consideration which the difficulties demand.” The Ledger noted the “orderliness and general spirit of give and take” that prevailed and hoped for a quick “return to normality,” but it was shocked into a rare silence editorially. The elected leaders of District 18 had been ignored and marginalised by hundreds of members who had insisted on an action that clearly undermined and contradicted the fundamental UMWA principle of union solidarity. Undoubtedly, there were many miners who remained committed to that principle and who were entirely opposed to the resolution, but the fact remained that a substantial majority at the meeting demanded the ouster of their law-abiding Austrian-born and German-born neighbours from employment in the mines. Proponents of unionism were profoundly discouraged.

Advocates of internment were delighted. In Vancouver, the staunchly Liberal Sun newspaper, habitually hostile to Bowser, took the unprecedented step of praising him. The newspaper editorialised that Bowser “had the hearty support of The Sun and all other Canadians who are interested in the welfare of the Dominion.” Acknowledging that the acting premier may have exceeded his powers, the editorial insisted he should be “congratulated anyway” and concluded: “Perhaps [the prisoners] have been wrongfully interned without the consent of the government at Ottawa, but the fact remains that they have been put out of harm’s way until the end of the war.”[18]

The Vancouver World agreed, arguing that the miners were forced to act because the federal authorities had long failed to do so and suggesting “many other classes of aliens” should also be interned. The Daily News-Advertiser of Vancouver acknowledged the injustice that internment would impose on “non-Teutonic natives of Austria-Hungary,” but said blame must be placed on offenders “on the other side of the ocean.” Its editorial position was that Britons and Belgian, Russian and French nationals should not be compelled to work alongside “offensive associates,” and noted that appeals to union solidarity were “of no avail against the national consciousness and sense of outrage.”[19]

Further encouraged by these wide-ranging expressions of approval, Bowser issued new orders from Victoria: Welsby was ordered to register all aliens — married as well as single men, naturalised or not. This sent his constables scurrying back to their home bases to comply. Registrations took place over the next three days, but the number of prisoners held at the skating rink did not increase as a result. CNPCC general manager William Wilson had hurriedly returned to Fernie. The CNPCC was no champion of the civil rights of enemy aliens; but it was profoundly alarmed at government and union interference with its prerogative to determine the composition of its workforce. Wilson was able to persuade Welsby not to proceed immediately with the internment of the married men as ordered by Victoria, who were all able to remain at work.[20]

However, new prisoners were brought in from Cranbrook and the lumber camps to the south of Fernie. Constable Dryden of Waldo brought in four men from the Ross-Saskatoon camp on 15 June; Constable Gorman of Elko delivered five from the Joseph Letcher camp on 18 June; and Constable Collins brought two more men from Cranbrook on 22 June.[21] Following established procedure, these men — several of whom were arrested while planning or attempting to cross into the United States — would normally have been held at the Fernie provincial jail for a short time before being transferred to the internment camp at Lethbridge. Improvising on a daily basis and with limited manpower available, it is not surprising that Chief Welsby decided to confine them, temporarily at least, at the skating rink.

Although Provincial Police constables at Hosmer and Corbin soon made the same inventories of enemy aliens as had their counterparts at Coal Creek, Michel, and Natal, prisoners were not taken — probably because the numbers at the skating rink were severely straining the ability of Welsby and his staff to cope. Except for those from Cranbrook and the lumber camps to the south of Fernie, only CNPPC employees were being held at Fernie.

As official documents have not survived, the number of those employees detained can only be approximated. The District Ledger later stated the number of men detained to be 317. If (as seems likely) that was a count of only UMWA members, there were 187 internees from Michel and Natal — where there had been no agitation at all about working with enemy aliens — and 130 from Fernie/Coal Creek. As the days passed, other newspaper reports of the number of men affected varied and fluctuated. The Victoria Daily Times, for example, on 19 June estimated the total number of internees held at the skating rink to be nearly 400. However, taking all police reports and other sources into account, inclusive of both CNPCC employees and others from the south, numbers appear to have peaked at around 330 on 22 June.[22] And from Alberta came news that miners just at Hillcrest in the Crow’s Nest Pass were following the precedent set by the Gladstone local union. Citing safety concerns, they were refusing to work underground with enemy aliens. The effect of Bowser’s internment initiative had crossed the provincial boundary.

By the end of the second week of the operation, the confusion surrounding the whole question of a provincially-ordered internment was receiving a great deal of press commentary both at the Coast and in Fernie. The confusion arose because Bowser had assumed — reasonably, but incorrectly — that the cooperation of federal authorities secured for the internment of miners working on Vancouver Island was transferrable to East Kootenay.

On that basis, he instructed Major Ridgeway Wilson to send the internees at Fernie to “whatever internment camp may be decided upon.” But the federal authorities were having second thoughts about the rule of law in a time of war. A representative of Internment Operations finally visited Fernie five days after the internment began. He met with Lieutenant-Colonel Mackay, Mayor Uphill, and Chief Welsby, and, as the Free Press reported, advised them that there “was no legal authority for interning these men.”

Apparently, the Proclamation of 15 August 1914 and the broad powers accorded by the War Measures Act were not sufficient to deal with Bowser’s internees. Those federal measures justified the internment of enemy aliens who had indicated (or were alleged to have indicated) loyalty to Germany or Austria-Hungary, who had attempted to flee to the United States, or who by virtue of being unemployed were placing stress on available civic relief funds. The employees of the CNPCC held at the skating rink had not professed support for Germany or Austria-Hungary, had not attempted to cross into the United States, had all registered with the police as required, and had undertaken to obey the laws of Canada. In addition, of course, they had all been employed and, uniquely, they were being detained by a provincial government.

Bowser told Prime Minster Borden he was “greatly perturbed” at the reluctance of Internment Operations to take charge of the prisoners, asking why the situation at Fernie should be seen differently than the detention of enemy alien miners on Vancouver Island, and warning that “riot and strike” could result from releasing the men held at the skating rink. He urged MPs for Victoria and Kootenay to personally lay his concerns before Borden in Ottawa and asked the MP for Comox-Atlin to wire Borden in support of the province’s internment initiative. Placing great emphasis on the seriousness of high unemployment, he hoped to extend his internment policy to the Granby mine at Anyox and the Britannia mine north of Vancouver.[23]

In Victoria, during comments to reporters about the situation in Fernie, Bowser rather clumsily attacked federal authorities for their lack of cooperation, criticising A.P. Sherwood, the Chief Commissioner of Police in Ottawa, for treating internees so well and for being “afraid of hurting their feelings.” At the same time, he was pleased with the announcement from the Britannia Mining Company that it would voluntarily discharge its enemy-alien employees.

In Fernie, the Free Press — a strong supporter of Bowser and the Conservatives — asked “Where are we at?” and answered “Who knows?” It noted that individuals representing the Department of Labour, the Immigration Branch, and the British Columbia Federation of Labour had all visited and departed without providing solution or resolution. Bowser emphatically denied the report in the Vancouver World newspaper that the internees would soon be freed and told reporters he had advised Prime Minister Borden that riots would break out in the mining camps if they were.

Agreeing that the potential for disorder was substantial, the Free Press reported that militia units based in Calgary were awaiting orders to leave for Fernie, and noted: “It would be a hardy man who would take the responsibility for turning these [internees] loose in this community now.”

Compounding the uncertainty caused by the hesitation of federal authorities was the fact that the internees had been given advice that their internment was illegal. Apart from the greater number of prisoners involved, the fundamental difference between the internment operation at Fernie and the roundup of miners executed on Vancouver Island was that the Fernie internees mounted a legal challenge. No such challenge had emerged from those arrested on Vancouver Island and there had been no impediment to transferring them to federal custody. But at Fernie, well into the second week of the camp, Internment Operations was clearly unwilling to accept responsibility for the internees.

It is distinctly possible that the advice about the illegality of the internment originated with the UMWA. Perhaps the supreme irony of the crisis is the fact that the most prominent defenders of the civil rights of enemy aliens were English-speaking executive members of the same union to which the English-speaking rebels owed their allegiance. David Rees and William Phillips had failed to influence the meeting calling for internment; Thomas Uphill in the chair could not play too significant a partisan role in that debate, but later insisted he saw no reason whatsoever for imprisoning the men at the ice rink. Taking advantage of its editorial control of the District Ledger, the executive mounted what was essentially a counterattack on Bowser’s fait accompli.

In an extensive editorial in its issue of 19 June, the newspaper laid out precisely the argument that had the acting premier so concerned. Recalling the Proclamation of 15 August, the Ledger reprinted in full the paragraph guaranteeing that those who “quietly pursued their ordinary avocations” could continue “to enjoy the protection of the law” and would not be “arrested, detained or interfered with.”

The editorial pointedly stated that the men held at the skating rink differed from those detained at Vernon and Lethbridge in that they had all signed the undertaking to obey the laws of Canada as required, that no charge had been laid against them, and that they had broken no law. Acknowledging that “dispassionate discussion and calm analysis upon any subject relative to the war” was problematic, the Ledger nevertheless drew readers’ attention to the principles of habeas corpus as “a precious safeguard of individual liberty against official tyranny.”

Unusually, the assessment presented by the UMWA newspaper was entirely consistent with the view held by one of Canada’s most prestigious business publications. The Canadian Mining Journal — while acknowledging that all known partisans of Germany working in Canadian mines “should be promptly interned” — insisted editorially that enemy aliens “striving to live as becomes decent citizens” should not:

The men employed in the mines have won their positions by their work, and, so long as their work is satisfactory to their employers and their conduct satisfactory to the public, it will be grossly unfair for anyone seeking personal interest to ask that they be refused employment.

The editorial did not specify whether it was condemning the miners of Coal Creek or William Bowser for “seeking personal interest,” but its disapproval of the internment is perfectly clear. The Free Press, in reprinting the editorial, was also stepping back from its initial enthusiasm for Bowser’s initiative.

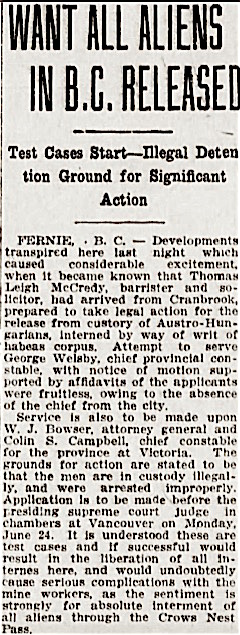

Collectively, the internees had attempted to raise $700 for legal fees. Although they fell short of the mark, Cranbrook lawyer Thomas Macredy agreed to apply for writs of habeas corpus in the names of Austrian-born internees Stephan Janastin, employed at Coal Creek since 1908, and Martin Bobrovski, who had come to Canada as a seven-year-old in 1891 and was employed at Michel.

Fernie lawyers — reportedly adopting the same superficially patriotic stance as that employed by the miners and the acting premier — had all refused to take the case. Macredy travelled to Fernie on 16 June to serve the affidavit on Chief Constable Welsby, and others were sent to Victoria for Bowser and Superintendent Colin Campbell. The applications were scheduled to be heard in the Supreme Court in Vancouver on Monday, 21 June.

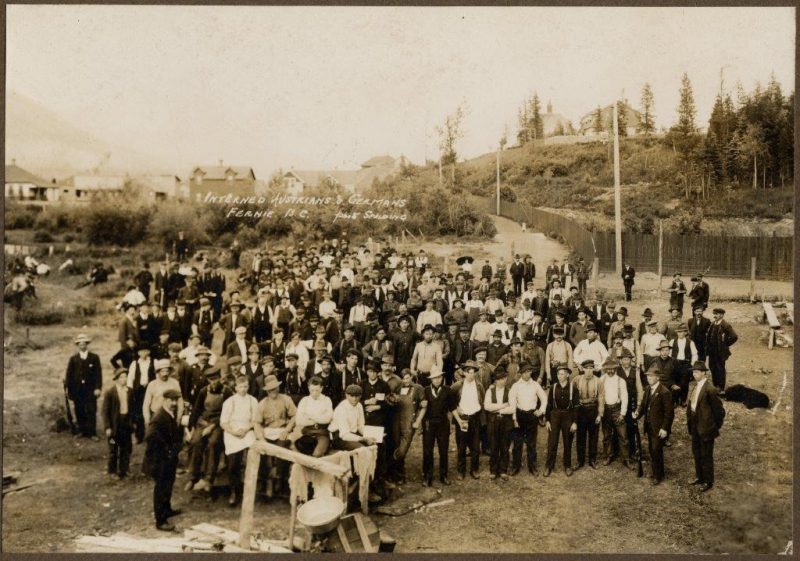

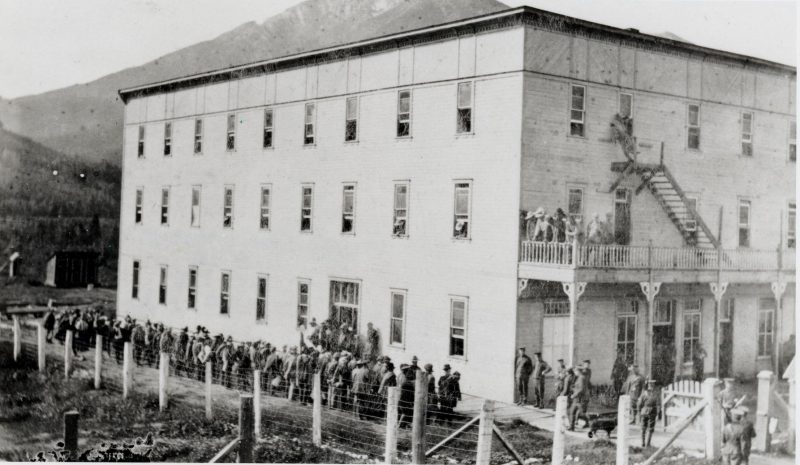

At some point during the unseasonably cool month of June, Fernie photographer Joseph Spalding managed to secure Chief Welsby’s agreement that the internment deserved to be visually recorded. Under overcast skies, the prisoners were gathered on the enclosed grounds behind the skating rink. With a handful of spectators watching from outside the barbed wire fence, with armed guards positioned around the perimeter and with Welsby standing authoritatively in the foreground, the interned men faced the camera.

Like a year-end school photograph, the faces of the supervising adult and those in his charge were recorded for posterity as Spalding captured a unique image for a new postcard. Unlike a typical school photograph, however, none of the faces revealed any evident pleasure in the occasion.

As the days passed and as uncertainty reigned outside the camp, life inside developed its patterns and routines. Cigarettes and tobacco were delivered to internees by well-wishers. Visitors were allowed into the compound with Welsby’s written permission and could talk to them freely from outside; books and newspapers were permitted if the recipients promised not to litter.

Three dozen special constables, on duty twelve at a time in eight-hour shifts, were supervised by one or two regular British Columbia Provincial Police officers. The Provincial Police were typically armed with standard issue 38-calibre Smith and Wesson or Ivor Johnson revolvers, and, like the unarmed special constables, they dressed in civilian clothes. Spalding’s photograph of the camp shows that, while the police also had access to rifles, in appearance they were indistinguishable from store clerks and bank tellers.

Cooking and cleaning was done by small groups of internees. The morning meal consisted of bread, porridge, and tea; the evening meal of meat, vegetables, bread and soup. Cleaning details kept the facility tidy by dumping accumulated rubbish in the Elk River. Reporters from the Fernie newspapers were allowed full access to the camp. The Ledger reporter commented on the sense of fellowship and the “general air of contentment” that prevailed. Indeed, his published column describes almost a holiday atmosphere:

Games of cards are indulged in, bursts of song enliven the monotony, and as there are quite a number who are musical executants on both wind and brass instruments, the tones of the accordion, cornet, [and] flute furnish excellent media for driving dull care away.

One tune frequently played was “It’s a Long Way to Tipperary.”[24]

But the reality is that this was a makeshift prison camp with an air of continuing uncertainty about what was to happen to the more than 300 men being held. The prisoners were still sleeping on the floor and the lack of bathing facilities was causing concern as “a possible menace” to the health of all. Seven men were released when they produced their naturalisation papers. Would they all be released if the legal challenge was successful? If Dominion authorities took over, would they be moved to Lethbridge, Vernon, or Banff?

The unusually wet June added generally overcast skies to the sense that Fernie was a troubled community. The court date for the internees’ legal challenge was postponed for a week at the request of Crown counsel acting on instructions from Bowser. When the week had passed, it was postponed again. The seven men who had managed belatedly to provide their naturalisation papers were no doubt relieved to be released. But for those still detained, how much longer could the admired “air of contentment” be sustained?

Bowser was not alone in being perplexed by the stalemate at Fernie. Federal authorities were faced with a serious problem. To continue to refuse responsibility for Bowser’s internees meant the legal challenge would proceed with the possible outcome — indeed, the probable outcome — favouring the appellants. That judgement would necessarily also apply to the prisoners arrested from the mining communities of Vancouver Island. The mass release of approximately 450 enemy aliens would cause outrage throughout British Columbia and that outrage would be directed not only towards Bowser’s Conservatives in Victoria. However, by their own assessment, Internment Operations admitted there were no legal grounds for the detention.

Bowser was seriously alarmed when advised by the Minister of Justice in Ottawa that the situation at Fernie was not consistent with that on Vancouver Island. No stranger to the law, Bowser was aware that the application for habeas corpus backed by provisions of the Proclamation of 15 August 1915 would certainly succeed. In desperation, he wired Borden on 25 June that he would then have no choice but to issue an order for the release of the internees. Concluding that a release was politically unacceptable, recognising that its approval of Bowser’s proposal for internment on Vancouver Island had been reckless, but with no legal grounds to detain employed enemy-alien who posed no discernible threat to domestic security, the federal government quietly decided to create those legal grounds.

The internees’ day in court — scheduled for 10 a.m. on 28 June — was yet again postponed. But to the dismay of the internees, Major General Sir William Otter, in command of Internment Operations nation-wide, issued orders that day to take charge of the camp at the skating rink from the Provincial Police.

Something had changed. Apparently, Internment Operations was no longer concerned about an absence of legal authority to detain the internees at Fernie; apparently the applications for writs of habeas corpus were no longer worrisome. Just as he was processing two additional German prisoners brought in from Wardner, Welsby received instructions from Victoria on 29 June to transfer command to federal authorities. He made preparations to comply immediately — probably with a great sense of relief. The changing of the guard took effect officially the next day.

An even greater sense of relief was no doubt felt in Victoria. Bowser had been let off the hook. The explanation for the Dominion’s sudden acceptance of responsibility became apparent to everyone else only when the applications for writs of habeas corpus were dismissed out of hand by a judge two weeks later in Vancouver. To the complete surprise of counsel representing the internees, the lawyer for the Crown presented a copy of Order-in-council 1501 passed 26 June (not yet gazetted, but clearly in response to Bowser’s desperate wire of the previous day) giving the Minister of Justice authority to intern — as he saw fit — enemy aliens working in the mines.[25]

Essentially, the order-in-council sanctioned the internment of enemy aliens whose simple presence in a workplace “may lead to disorder.” It was devised with the specific situation at Fernie uppermost in mind, but was worded such that there could be no subsequent legal challenge from Vancouver Island internees or anyone else. Swollen with densely worded arguments attempting to justify its conclusion, the proclamation seems just as clumsy as the miners’ resolution of three weeks earlier. The Daily News-Advertiser in Vancouver summarised its intent thus:

It provides in effect, that because of the possibility of danger among enemy aliens and British subjects who may be at work together in mines and at other occupations in Canada, it is considered wise that the enemy aliens shall be taken care of at public expense.

It was knowledge of this new order-in-council that had allowed Internment Operations to suddenly announce its takeover of the camp two weeks earlier. The lobbying campaign orchestrated by Bowser had ultimately succeeded in persuading Borden’s government that social disorder was probable in Fernie if the internees at the skating rink were released. Of course, the government in Ottawa also recognised that the legal and constitutional mess created by provincial internment had to be cleaned up.

At a single stroke, the protection accorded by habeas corpus was withdrawn from enemy aliens in mining occupations and the legal authority was created for Internment Operations to take custody of Bowser’s internees. Assurances published with such confidence by the District Ledger during the preceding months that law-abiding enemy aliens would be protected by British justice were apparently naïve. The newspaper reported simply and rather weakly that internment at the rink “had been legalized, although this was not originally so.”

Significantly, the copycat strike at the Hillcrest mine in Alberta was also settled at the end of June, but without any reference to the new order-in-council. The UMWA local union and the coal company agreed to leave matters in the hands of Internment Operations. All miners — British and enemy-alien alike — were back at work. But a comparable resolution could not have been achieved at Fernie. Bowser’s immediate intervention had determined that internment there was the only possible outcome.[26]

The official court reporter at Fernie advised the Department of Labour in Ottawa at the end of June that, apart from the few prisoners from the south country and after the release of those with naturalisation documents, 308 employees of the CNPCC remained as prisoners.[27] The transfer of responsibility for the internees did not occur without difficulty. The special constables recruited by the Provincial Police to act as guards were advised they could continue in that capacity, but only at the military rate of pay — namely, $1.10 per day plus a living allowance of 85 cents. Unhappy with such a reduction in pay, most refused to continue. Their places were taken by men of the 107th East Kootenay Regiment, initially unarmed and without uniforms.

More significant than the change of guard was a change of policy. The officer taking charge of the camp was Lieutenant-Colonel Joseph Mackay, the local man responsible for recruitment in East Kootenay and much admired for his integrity. Mackay was not an admirer of Bowser’s internment order, but military proprieties prevented him from publicly criticising it. He would later privately advise Otter that he could not understand why such an order was given, describing the local Slavic population as being amongst Fernie’s best citizens, of no danger to the state or anyone else.[28] Upon taking command, he immediately requested and received permission to examine the justification for internment of each man individually, intending to release those for whom no such justification could be found. It was a fundamental reversal of Bowser’s policy.

On his first day in command, Mackay discharged several of the men designated as Bohemians who had been arrested in Michel. By mid-July, his comprehensive review resulted in the release of 157 men — approximately half the internees. It is likely that Mackay deemed many of those released to be “friendly aliens,” a categorisation recently adopted by federal authorities to describe ethnic minorities from within Austria-Hungary who were thought to be hostile to that country.[29] The Fernie correspondent to the Lethbridge Herald reported that amongst the prisoners released were one American citizen and one Italian mistakenly captured in the initial round-up. The Free Press noted only that Mackay had “weeded out” those who were incapable of military duty and these had “returned to their homes.” Many did visit friends and relatives at Coal Creek, but Mackay had set one condition for their release: none of them were to return to work for the Crow’s Nest Pass Coal Company.

With Internment Operations in charge, the long-term organisational aspects of the camp had to be assessed. For those internees remaining in custody, the question of locating them on a more permanent basis demanded urgent attention. Facilities at the skating rink would be completely inadequate for a winter camp. It was anticipated that internees were to be sent to Lethbridge or Banff. In mid-July, another visit by Ridgeway Wilson was intended only to inspect conditions at the skating rink, but it resulted in a reassessment of the possibility of establishing a permanent camp locally. With Lieutenant-Colonel Mackay, Major Wilson visited the abandoned Morrissey townsite and was impressed by what he saw.[30]

At the end of July, citizens of Hosmer — devastated by the closure of the CPR coal operation a year earlier — saw an opportunity to reverse their community’s decline and suggested a winter camp should be located there; Mackay promised to consider the possibility. He may have done so, but when Major General Otter arrived at Fernie in mid-August for an inspection of his own, he was greeted with a renewed lobbying effort to locate the winter camp at Morrissey Mines. Along with the officers of the 107th East Kootenay Regiment, meeting him at the train station were representatives of the Fernie Board of Trade. No trip to Hosmer took place, but in the company of business partners Amos Trites and Roland Wood, CNPCC general manager William Wilson and assistant manager R.M. Young, three military officers, and Fernie mayor Thomas Uphill, he travelled by automobile to inspect the abandoned townsite at Morrissey.

That evening, a special meeting of the Board of Trade was convened to present Otter with the business case for a camp at Morrissey. On hand was a telegram from Bowser urging that internees should be detained locally. Trites pointed out that the region’s dangerous roads would benefit greatly from internees working on improvements and assured Otter that supplies for the proposed camp would be provided by local merchants at very economical rates; William Wilson stated his opposition to the internment, but offered the same assurance for rental of the townsite and noted the company-owned waterworks could easily be made operational again; and Mayor Uphill, while also objecting to the internment, nevertheless agreed it would be best to keep local residents close to home. When Otter announced he was willing to consider locating a camp at Morrissey, members of the District Conservative Association in attendance, recalling their resolution of 9 June, must have been very pleased indeed.

William Bowser made a brief stop in Fernie on 29 September on his way to Ottawa. Historical records are silent on whether or not he had time or the inclination to take a look at the internment camp at the skating rink, but that camp was closing. More precisely, it was being relocated. Morrissey Mines was ready to receive its new residents. A few internees left Fernie on 28 September to assist with final preparations.

During the first two weeks of October the skating rink was emptied of its prisoners — a half dozen German and nearly 160 Austro-Hungarian enemy aliens. The last prisoners left Fernie on Sunday, 17 October. The arrangements surrounding the transfer must have compromised established security procedures — during the last two weeks of September and the first week of October, five prisoners escaped.[31]

The physical internment at Fernie was over and the camp was out of sight — but it cannot have been out of mind. For a period of four months, the skating rink had been the site of a makeshift prison. Miners acting against the policies of their union and a politician in pursuit of electoral advantage had combined to create a social disaster in the Elk Valley. Anyone hopeful that the transfer of internees to Morrissey represented the end of an unpleasant episode would soon be forced to acknowledge the extent of the damage revealed by a complex of consequences — some predictable and some unforeseen.

Premier Bowser stopped talking publicly about internment and there are indications that he had learned a serious lesson from the repercussions of his interference in the province’s coalfields. During a brief period of employment by the Crow’s Nest Coal Company early in 1916, Albert “Ginger” Goodwin wrote from Fernie to Bowser objecting to the internment of Cumberland miner Peter Janoni. In reply, Bowser advised Goodwin: “I have nothing to do with the internment of any of the aliens…”[32] Not a statement particularly near the truth, but it does indicate a reluctance to have anything further to do with internment.

A couple of months later, when the CNPCC continued to see its labour force depleted by remarkably high recruitment levels, Fernie lawyer Sherwood Herchmer wrote privately to Bowser. He warned that, unless recruitment in the region was controlled, the business community feared “the wheels of industry will be closed down” because the coalmines would have to cease production for lack of manpower. Bowser replied that military matters were a federal responsibility, concluding: “[it] would not do for us to encroach on their territory.”[33]

The labour shortage In Fernie and throughout the province should have underlined the absurdity of Bowser’s internment initiatives, yet so strong did the patriotic impulse remain that Bowser’s critics seem to have remained silent on that point. In the Elk Valley, the exceptional success of recruitment drives amongst local miners meant the CNPCC could not meet the surging demand for coal and coke. The overwhelming majority of the nearly 900 local recruits identified by the Free Press in May 1916 had been drawn from employment with the CNPCC. In addition, more than 300 of the company’s foreign-born employees had been interned in June 1915. Although many had since been released — Mackay had discharged fifty more from the Morrissey camp in January — they were still prohibited from returning to work in the mines of the CNPCC.

The coal company was becoming desperate. In April, it had formally requested the release of the remainder of its interned former employees and permission for them to return to work for the CNPCC. Lobbying in support of its request, the company submitted testimonials to the good character of its interned employees from Lieutenant-Colonel Mackay and a number of Fernie businessmen. Both general manager William Wilson and company president Elias Rogers advised Major General Otter in May that the CNPCC was 500 men short and “suffering seriously” from an inability to fill orders.[34] The internees of June 1915 were sorely missed less than a year later.

But the CNPCC was not the only employer requesting the release of internees. Labour shortages had become acute in many sectors of the national economy. In response, the federal government initiated a policy of release for those internees who were not deemed to pose a threat to security and those who had been interned essentially because they were destitute.

To be eligible for release, the internee had to be certain of employment upon release, while the employer had to guarantee payment at current wage rates and demonstrate the job could not be filled by a British subject. Under these new terms, employment at Coal Creek again became a possibility. However, most of the internees of June 1915 had already been released and most of them had left the district. In early June, seventeen prisoners were released from Morrissey specifically to work for the CNPCC, six of them in aboveground occupations at Coal Creek, the rest at Michel and Natal.[35] By the end of July, fifty internees from Banff were also released specifically to work for the CNPCC, but only at Michel. Otter noted darkly that complications were “apt to arise” if they were placed at Coal Creek.[36]

If there was any expression of discontent in connection with former internees returning to work at Coal Creek or Michel, it went unrecorded. In the Vancouver Island coalfields, however, the release from the Edgewood internment camp of former Island miners caused uproar. The matter became a major issue at Nanaimo in the provincial election campaign in September, with all levels of government being sharply criticised for allowing such a “mistake” to happen.

Apparently having learned little from experience after all, Bowser once again plunged in. He sent a telegram to the local Conservative candidate assuring him that he had personally instructed the Provincial Police to re-arrest all released internees and to hold them at the Nanaimo lock-up until they could be returned to federal custody. Nanaimo city council wrote to Prime Minister Borden claiming jobs were being taken from British subjects and urging re-internment. When Mayor Uphill and his council in Fernie received a request for support of that initiative from their Nanaimo counterparts, the matter received only a brief discussion before being quietly filed.[37]

The quiet acceptance of enemy-alien workers at Fernie stemmed from recognition of how desperately needed they were. The labour crisis was steadily worsening. Regional recruitment figures are difficult to confirm, but William Wilson stated in September that 1280 men had joined the colours from the Fernie district and that almost all had been employees of the CNPCC. Accurate or exaggerated, the figure was alarming. So dire had its labour shortage become, the CNPCC took the unprecedented step of requesting the complete suspension of local recruiting.[38]

Following the example of the British government, which in June had forbidden further recruitment of coal miners in the United Kingdom, Canadian authorities acted quickly. Issued in mid-September, Military Order No. 448 stated that, effective immediately, recruiting was entirely forbidden everywhere in “the Crow’s Nest Pass Coal Co. mining district.” Only the 107th East Kootenay Regiment, with its obligation to garrison the Morrissey internment camp, was exempted from the ban.

Military Order No. 448 was unique — nowhere else in Canada was overseas recruitment forbidden during the First World War — and it was as much a consequence of Bowser’s internment initiative as the high level of recruitment. The ability of the region’s small population to provide more recruits for the war in Europe was near exhaustion by the fall of 1916. Clearly, the more than 300 men forced from their jobs a year earlier — all of them ineligible for military service in Canada — would have prevented the labour shortage from becoming a labour crisis for the CNPCC. But apart from the very few finally released from Morrissey in June, those men had been forced to leave the district to seek employment elsewhere.

Bowser made his only appearance of the election campaign at Fernie in early August. He was met at the train station by a brass band and members of the Conservative Association, but was given a frosty reception at the public meeting he attended with his local candidate. In modern terminology, Thomas Uphill, the popular mayor of Fernie, was a star candidate. As secretary to the local miners’ union, he was precisely the type of candidate calculated to appeal to the working-class, whose votes Bowser had long sought to attract. He would win election to the Legislature under the Labour Party banner first in 1920 and in every election thereafter until his retirement in 1960. He remains the longest-serving MLA in the province’s history. But making his first appearance on the provincial stage in 1916 as a Conservative, he was defeated.

The results of British Columbia’s general election proved to be a humiliating defeat for the governing party. Overwhelmingly, working-class voters joined their middle-class counterparts in favouring Liberal candidates over Conservative ones. Bowser’s attempt to woo the working-class voter through an aggressive internment policy had failed, and he narrowly avoided personal defeat in Vancouver. Liberal candidates were successful in both Fernie and Nanaimo. In the labour constituency of Fernie, the Conservative gamble with a labour candidate — and his gamble with the Conservatives — had proved unsuccessful. An elector at Fernie, Uphill’s own brother-in-law later stated he could not persuade himself to cast a Conservative vote.[39]

The miners’ strike of June 1915 typically is viewed as an East Kootenay version of the riots in Victoria over the sinking of the Lusitania, a gentler outburst and somehow delayed a month, yet caused by the same sense of patriotic outrage. But beneath that veneer of patriotism, the miners were acting fundamentally from economic motives, pursuing self-interest at the expense of co-workers made vulnerable by a European war. However, there is no evidence to suggest they would have acted at all without the example set by Bowser’s intervention in the coalfields of Vancouver Island. From an entirely different perspective, they simply shared his hypocrisy and opportunism. The wildcat strike, the temporary internment camp at Fernie, the location of a permanent camp at Morrissey, the labour crisis of 1916, the cancellation of recruitment — all stemmed from the same supposedly patriotic action launched by Bowser in May 1915.

Under the guise of patriotism, vulnerable immigrants were targeted in hopes of gaining votes. That action brought Bowser none of the anticipated electoral benefit, but resulted in severe and lasting consequences for interned unemployed immigrants and for the interned coal miners of Vancouver Island. Most dramatically, those consequences were felt by hundreds of hopeful migrant workers employed by the Crow’s Nest Pass Coal Company and by everyone living in the small East Kootenay city of Fernie.

*

[1] Patricia E. Roy, Boundless Optimism: Richard McBride’s British Columbia, (Vancouver: UBC Press, 2012), p. 270.

[2] Bohdan S. Kordan, No Free Man: Canada, the Great War, and the Enemy Alien Experience (Montreal and Kingston: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 2016), pp. 96-99; Minutes of special meeting, 20 May 1915, City of North Vancouver, http://www.cnv.org/your-government/council-meetings/council-meeting-minutes/council-minutes-archive; Nanaimo Free Press, 14 May 1915, p. 2.

[3] District Ledger, 22 May 1915, p. 1; Victoria Daily Times, 13 May 1915, p. 2; W.J. Bowser to Robert Borden, 21 June 1915, Premiers’ Records, Series IX, GR 0441, vol. 398, pp. 524-526, BCA.

[4] Ladysmith Chronicle, 26 May 1915, p. 1; Victoria Daily Colonist, 26 May 1915, p. 6.

[5] Reports of Constable George Allen, May and June 1915; Report of Constable Alex Mustart, May 1915, Provincial Police Force, GR 0445, box 24, file 4, BCA.

[6] Prison records nearly agree with the figures cited in newspapers: 51 prisoners under military guard were received at Saanich on 28 May. Saanich Prison Farm Records, GR 0306, vol. 1, p. 550, BCA.

[7] Nanaimo Free Press, 28 May 1915, p. 1, and 1 June 1915, p. 1.

[8] Cumberland Islander, 5 June 1915, p. 8; Report of Robert Mills, June 1915, Provincial Police Force, GR 0445, box 21, file 7.

[9] Report of Joseph Boardman, June 1915, Provincial Police Force, GR 0445, box 21, file 2, BCA; Report of John English, June 1915, Provincial Police Force, GR-0445, box 23, file 13, BCA.

[10] The CNPCC figures, which may include clerical and salaried staff, are derived from a report sent by the official court reporter at Fernie to the Department of Labour. See Report by Fred G. Perry, 28 June 1915, Library and Archives Canada (hereinafter LAC), Department of Labour, Strikes and Lockouts, RG 27, vol. 304. The other figures are from the Vancouver Daily Province of 8 June 1915, p. 1. The Lethbridge Telegram put the number of German and Austro-Hungarian employees at precisely 152. The Lethbridge Daily Herald agreed with that figure, its Fernie correspondent stating there were 32 Germans and 120 Austro-Hungarians. See Lethbridge Telegram, 10 June 1915, p. 1; Lethbridge Daily Herald, 8 June 1915, p. 1.

[11] Lethbridge Daily Herald, 8 June 1915, p. 1.

[12] J.D. McNiven to Deputy Minister of Labour, 23 June 1915, Royal Canadian Mounted Police, RG 18, vol. 490, file 433-1915, LAC. The wording was reported differently in the Lethbridge Daily Herald, 9 June 1915, p. 1. The Herald had it as: “Resolved, that the men as Britishers, and others who are friendly, are willing and will work, but not under present conditions, that is, not with alien enemies.”

[13] Fernie Free Press, 20 August 1915, p. 1.

[14] Provincial Police Force, GR-0445, box 21, file 13, BCA; W.J. Bowser to Robert Borden, 16 June 1915, Premiers’ Records, Series IX, GR 0441, vol. 398, p. 514, BCA.

[15] Provincial Police Force, GR-0445, box 21, file 2, BCA; Fernie Free Press, 11 June 1915, p. 1.

[16] Provincial Police Force, GR 0445, box 21, file 5, BCA; Lethbridge Daily Herald, 14 June 1915, pp. 1 and 3.

[17] Provincial Police Force, GR 0445, box 23, file 13; box 24, file 6, BCA; Cranbrook Herald, 17 June 1915, p. 4.

[18] Vancouver Sun, 12 June 1915, p. 4.

[19] Vancouver World, 10 June 1915, p. 6; Daily News Advertiser (Vancouver), 9 June 1915, p. 4. Throughout June, while the newspapers focussed upon the patriotic motivation of the miners, Bowser continued to address the problem presented by the province’s “over-abundance of labourers.” He wrote to railway officials and prairie politicians attempting to secure special rates for labourers wanting to seek employment in Saskatchewan and Alberta. Premier, GR-0441, box 166, file 3, BCA.

[20] Minutes of meeting, 13 September 1915, GA, Crowsnest Resources Limited Fonds, Crow’s Nest Coal Company, Series 1, Minutes, Directors’ Meetings, M-1561, vol. 9, Minute Book, p. 262.

[21] Provincial Police Force, Superintendent, 1912-1922, GR 0057, box 22, file 2 and file 14, BCA; Provincial Police Force, GR 0445, box 21, file 5 and file 10; Cranbrook Herald, 24 June 1915, p. 4.

[22] Fernie Free Press, 11 June 1915, p. 1; Lethbridge Daily Herald, 15 June 1915, p. 1; District Ledger, 19 June 1915, p. 1 and 17 July 1915, p. ?; Victoria Daily Times, 19 June 1915, p. 7. An employee of the Department of Labour wrote that 314 Austro-Hungarians and six Germans were being held as of 23 June. J.D. McNiven to Deputy Minister of Labour, 23 June 1915, Royal Canadian Mounted Police, RG 18, vol. 490, file 433-1915, LAC.

[23] W.J. Bowser to Robert Borden, 16 June 1915; W.J. Bowser to G.H. Barnard, 14 June 1915. BCA, Premiers’ Records, Series IX, GR 0441, vol. 398, pp. 504-507, 514.

[24] District Ledger, 19 June 1915, p. 1; Lethbridge Daily Herald, 21 June 1915, p. 4.

[25] Privy Council Office, Series A-1-a, RG 2, LAC. The full text of the Order-in-council is found in Frances Swyripa and John Herd Thompson, Loyalties in Conflict: Ukrainians in Canada during the Great War (Edmonton: Canadian Institute of Ukrainian Studies, 1983), pp. 177-178. Appearing for Macredy, Vancouver lawyer Clarence Darling attended all court dates in Victoria. See District Ledger, 24 July 1915, p. 4 and Victoria Daily Times, 28 June 1915, p. 12.

[26] That the absence of governmental response permitted a quick resolution of the Hillcrest strike is made clear by the reports submitted by J.D. McNiven to the Deputy Minister of Labour. Royal Canadian Mounted Police, RG 18, vol. 490, file 433-1915, LAC.

[27] Report by Fred G. Perry, 28 June 1915, Department of Labour, Strikes and Lockouts, RG 27, vol. 304, LAC.

[28] Mackay to Otter, 23 May 1916, Records of the Secretary of State, Internment Operations Branch, RG 6 H1, vol. 754, file 3219, LAC.

[29] Kordan, No Free Man, pp. 132-133.

[30] Fernie Free Press, 16 July 1915, p. 1. Back in Victoria, Ridgeway Wilson was soon promoted to Lieutenant-Colonel while supervising the final touches to the building for which he is most remembered — the Bay Street Armoury, which opened in November 1915.

[31] List of Credit Balances due Escaped Prisoners of War, 19 November 1920, Records of the Secretary of State, Internment Operations Branch, RG 6 H1, vol. 819, file 1995, LAC.

[32] Goodwin to Bowser, 6 March 1916; Bowser to Goodwin, 13 March 1916, Premier, GR-0441, box 171, file 3, BCA.

[33] Herchmer to Bowser, 15 May 1916; Bowser to Herchmer, 20 May 1916, Premiers’ Papers, GR-0441, box 173, file 1, BCA.

[34] James Mason to Otter, 12 May 1916; Elias Rogers to Otter, 12 May 1916, Records of the Secretary of State, Internment Operations Branch, RG 6 H1, vol. 754, file 3219, LAC.

[35] Captain Shaw to Otter, 7 and 8 June, 1916, Records of the Secretary of State, Internment Operations Branch, RG 6 H1, vol. 754, file 3219, LAC.

[36] Otter to A. McNeil, 22 May 1916, Records of the Secretary of State, Internment Operations Branch, RG 6 H1, vol. 754, file 3219, LAC.

[37] Nanaimo Free Press, 12 September 1916, p. 1; 26 September 1916, p. 1; Fernie Free Press, 22 September 1916, p. 1.

[38] Minutes of meeting, 11 September 1916, GA, Crowsnest Resources Limited Fonds, Crow’s Nest Coal Company, Series 1, Minutes, Directors’ Meetings, M-1561, vol. 9, Minute Book, p. 288.

[39] Accession No: T3338.1, “Tribute to Tom Uphill” cassette tape, BCA.

*