#276 How a whistleblower dies

March 30th, 2018

Alan Fry (1931-2018)

“I have said more than once in frustration that if I had the power of God, I would put everyone on earth into a huge pot and stir them up so thoroughly they would come out all the same colour, probably some shade of brown. And there wouldn’t be any whites to lord it over everyone else.” – Alan Fry

*

Whistleblowers are seldom cited as heroes—especially those who can be dismissed as crackpot racists.

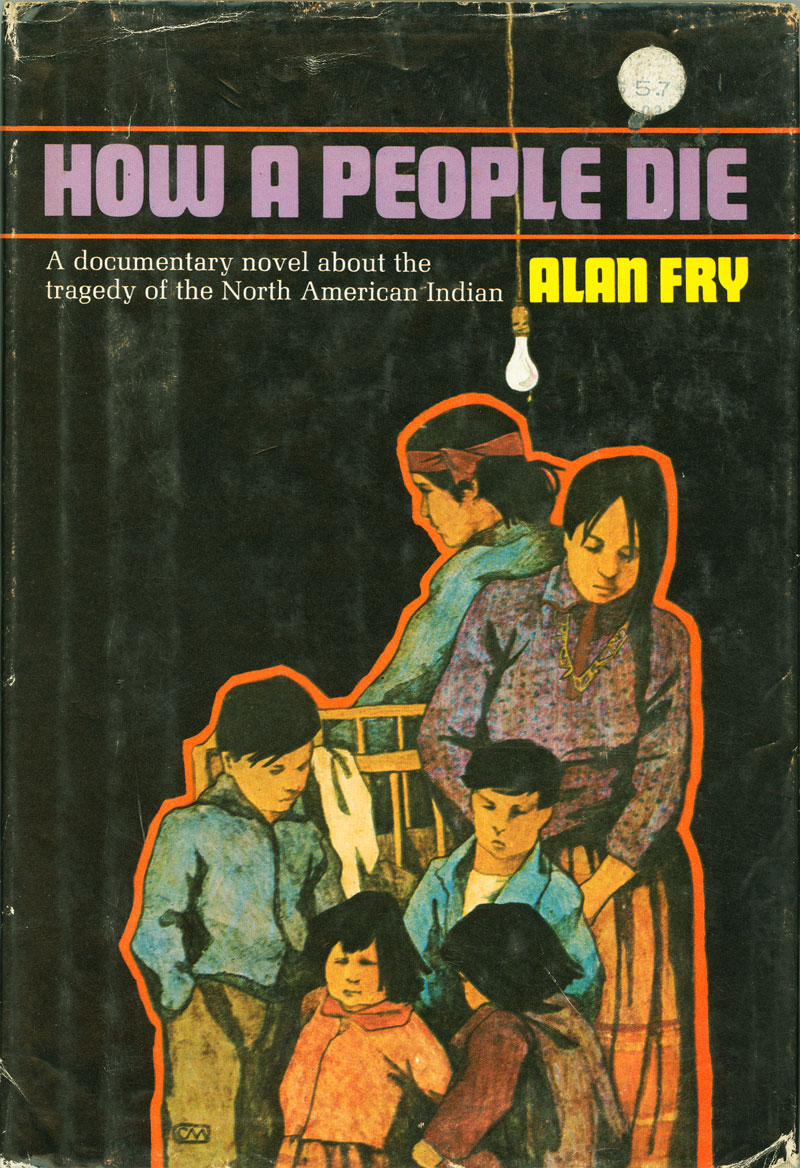

The importance of Federal Indian Agent Alan Fry’s first novel and second book, How a People Die (Doubleday 1970; Harbour 1994), has therefore gradually been glossed over, even disparaged, now that Canadian society does not wish to countenance a white man’s first-hand reportage on social decay on Indian reserves in the 1960s.

Published on the heels of Cree leader Harold Cardinal’s The Unjust Society (1969), Fry’s chilling descriptions of degradations he witnessed in central British Columbia—truthful or fictional—nonetheless ushered in a new era of realistic writing about Canada’s First Nations.

How a People Die concerns the death of an infant named Annette Joseph on the fictitious Kwatsi Reserve, a collection of shabby houses strewn with empty bottles. Examining the unsanitary conditions surrounding the death, RCMP Corporal Thompson, a veteran of 15 years on the force, takes the controversial measure of charging the infant’s parents with criminal neglect. The question soon arises among the characters of the story as to who should be held blameworthy for the tragedy.

How a People Die concerns the death of an infant named Annette Joseph on the fictitious Kwatsi Reserve, a collection of shabby houses strewn with empty bottles. Examining the unsanitary conditions surrounding the death, RCMP Corporal Thompson, a veteran of 15 years on the force, takes the controversial measure of charging the infant’s parents with criminal neglect. The question soon arises among the characters of the story as to who should be held blameworthy for the tragedy.

“Tell us how a people die,” says one of the Indigenous characters, “and we can tell you how a people live.”

The editor of the novel, Doug Gibson, has commented in a letter: “The title, as I recall, came in ready-made from him, and I never queried it. Until, that is, the book was out and doing well, and I was visiting bookseller Bill Duthie in his store downtown, and he started to tease me gently about having an ungrammatical title. He was right, of course, but for most of us, the immediate link of the plural verb with a noun that normally is plural was enough to make it slip by unnoticed. So, Bill was right, but Alan Fry, seeking colloquial punch, was right, too, I think. And the courage of an Indian Affairs guy, working in the field, writing such a novel, was extraordinary, and I realized that right from the start. Can you imagine such a thing

today?”

Also appearing in the aftermath of George Ryga’s The Ecstasy of Rita Joe at the Vancouver Playhouse, Fry’s hard-hitting novel further forced British Columbians to wake up to the plight of marginalized First Nations. For his efforts, Fry was branded a racist for stating that Indigenous parents ought to be held more accountable for child welfare and pilloried for his unscientific assertion that “alcoholism is an inheritable disease and Indian people inherit it to a greater extent than do non-Indians.” This year, Tomson Highway has made a similar assertion – suggesting a perceived ‘weakness’ for alcohol could be genetic — in his new book on indigenous literature but there has yet to be any backlash.

Most novels by British Columbians received precious little attention prior to Fry’s fictional debut. A reviewer for the New York Times Book Review described it as “. . .one of the most sensitive and incisive statements on human alienation I have ever seen.”

Fry’s introduction to a reissued edition of How a People Die contains an amalgam of statistical evidence of violence and familial dysfunction among First Nations. “It is my firm conviction that the succession of increasingly destructive lifestyles [on Indian reserves] can be traced back to the end of liquor prohibition to status Indians in the decade following the Second World War,” he writes. To further make questionable his opinions and observations, Fry divulges he was himself an alcoholic. He also relates an incident from his boyhood when an aboriginal male teenager allegedly tried to cajole him into a sexual encounter in the woods.

To further his contention that dependency on alcohol can be overcome, he cites the example of the Alkali Lake Band in the Chilcotin, southwest of Williams Lake, that managed successfully to prohibit alcohol in its midst, as initiated largely by Phyllis and Andy Chelsea and recorded in the community-produced film The Honour of All: The Story of Alkali Lake.

Fry also asserted, “Indian self-government must not be so structured that women and children living under such a government have less protection than is afforded to other Canadian citizens by other levels of government.” More reprehensibly by today’s standards, Fry wrote, “Primary responsibility for recovery lies with the people themselves. Past injustice is not the issue…”

All of which serves to explain why Alan Fry’s significance in B.C.’s literary history has been largely expunged.

Alan Fry was born and raised on a family ranch near Lac La Hache, B.C. in 1931. Although some of his ancestors were farming Quakers in Wiltshire, his grandfather Roger Fry, a member of the Fry family that prospered in the chocolate business, was a Cambridge graduate who kept company with the Bloomsbury Group. Alan Fry contended his own father immigrated to the B.C. interior to escape Roger Fry’s shadow. After more than 20 years of working in northern and central B.C., including fifteen years as an Indian agent, and three more realistic novels about life in the B.C. Interior, Fry quit working for the Department of Indian Affairs out of frustration and settled in the Yukon in 1974.

Alan Fry was born and raised on a family ranch near Lac La Hache, B.C. in 1931. Although some of his ancestors were farming Quakers in Wiltshire, his grandfather Roger Fry, a member of the Fry family that prospered in the chocolate business, was a Cambridge graduate who kept company with the Bloomsbury Group. Alan Fry contended his own father immigrated to the B.C. interior to escape Roger Fry’s shadow. After more than 20 years of working in northern and central B.C., including fifteen years as an Indian agent, and three more realistic novels about life in the B.C. Interior, Fry quit working for the Department of Indian Affairs out of frustration and settled in the Yukon in 1974.

Since moving the Yukon, Alan Fry repeatedly wrote letters and editorials warning his fellow Yukoners about the perils of racism of all stripes. “I have said more than once in frustration,” he wrote, “that if I had the power of God, I would put everyone on earth into a huge pot and stir them up so thoroughly they would come out all the same colour, probably some shade of brown. And there wouldn’t be any whites to lord it over everyone else.”

The controversial nature of How A People Die unfortunately overshadowed the appeal of possibly his superior novel, The Revenge of Annie Charlie, an often humourous, sly tale that describes Indigenous characters outwitting non-Indigenous society. It was followed by Come A Long Journey and The Burden of Adrian Knowle.

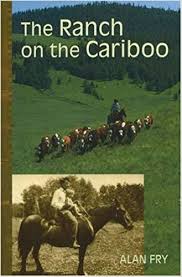

In Whitehorse, Alan Fry also co-authored Wilf Taylor’s memoir Beating Around the Bush: A Life in the Northern Bush (Harbour, 1989). Fry’s first non-fiction book, The Ranch on the Cariboo (Doubleday 1962) was later republished by Touchwood Editions. It describes a teenager’s introduction to manhood and ranching in the early 1940s. Fry’s Survival in the Wilderness (1981) describes techniques and equipment required to survive emergencies in the wilderness based on Fry’s own experiences.

In Whitehorse, Alan Fry also co-authored Wilf Taylor’s memoir Beating Around the Bush: A Life in the Northern Bush (Harbour, 1989). Fry’s first non-fiction book, The Ranch on the Cariboo (Doubleday 1962) was later republished by Touchwood Editions. It describes a teenager’s introduction to manhood and ranching in the early 1940s. Fry’s Survival in the Wilderness (1981) describes techniques and equipment required to survive emergencies in the wilderness based on Fry’s own experiences.

Editor Doug Gibson first contacted Fry in 1969 and remained friends with him, last visiting Fry in January of 2016 when Gibson went to Whitehorse on a book tour. They tended to chat with one another by phone on a monthly basis.

“He was a very fine man and an important part of Canadian writing,” Gibson says, “especially for his role in alerting us to the scale of what we then called “the Indian problem”. That this brutally frank account, How A People Die, was written by an employee at the Department of Indian and Northern Affairs led to a storm of protest, with national leaders demanding that he must be fired.

“Alan went to work with the local band on Quadra island and said he’d leave the decision up to them. They asked him to stay on and told the national leaders to back off. Because of our monthly contact, I was aware of the health problems that caused him to lose one leg a year ago, then the other early this year. I know that he and his wife Eileen were pleased to welcome the end.”

Alan Fry, a double amputee, died in Whitehorse on March 23, 2018.

“Alan Fry was one of B.C.’s most successful writers in the 1970s and ‘80s,” says publisher Howard White. “That he has been so completely forgotten is a loss, as well as a caution to writers of today.”

The Ranch on the Cariboo (Doubleday 1962; Touchwood)

How A People Die (Doubleday, 1970; Harbour, 1994).

Come A Long Journey (Doubleday, 1971)

The Revenge of Annie Charlie (Doubleday, 1973; Harbour, 1990).

The Burden of Adrian Knowle (Doubleday, 1974).

Survival in the Wilderness (Toronto: Macmillan, 1981), aka Wilderness Survival Handbook: A Practical, All-Season Guide To Short-Trip Preparation And Survival Techniques For Hikers, Skiers, Backpackers, Canoeists… (New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1981).

Taylor, Wilf & Alan Fry. Beating Around the Bush: A Life in the Northern Bush (Harbour, 1989).

Leave a Reply