#277 The new turf of Indigenous Lit

March 30th, 2018

From Oral to Written: A Celebration of Indigenous Literature in Canada, 1980-2010

by Tomson Highway

Vancouver: Talonbooks, 2017

$29.95 / 9781772011166

Reviewed by Deanna Reder

*

The publisher of The Ormsby Review, Alan Twigg, pioneered the topic of Indigenous bibliography with Aboriginality: The Literary Origins of British Columbia (Vancouver: Ronsdale 2005). Funding for this first-ever compilation of all First Nations authors of one Canadian province was zilch.

The publisher of The Ormsby Review, Alan Twigg, pioneered the topic of Indigenous bibliography with Aboriginality: The Literary Origins of British Columbia (Vancouver: Ronsdale 2005). Funding for this first-ever compilation of all First Nations authors of one Canadian province was zilch.

Fast forward ten years and our reviewer Deanna Reder received a $352,000 grant from the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council (SSHRC) for a project called “The People and the Text: Indigenous Writing in Northern North America up to 1992.

Now Métis scholar Deanna Reder, Chair of the Department of First Nations Studies at SFU, praises and find faults with Tomson Highway’s unprecedented overview of Indigenous literature, From Oral to Written: A Celebration of Indigenous Literature in Canada, 1980-2010. A remarkable personal essay by Tomson Highway that precedes the bibliographic summaries is referenced as ‘problematic’ herein, but anyone who has an abiding appreciation of Highway’s work might want to have a look at it for biographical reasons.- Ed.

*

Eminent Cree author Tomson Highway’s From Oral to Written, released by Talonbooks in 2017, is beautifully flawed, inspiring the reader with tremendous lists of books by Indigenous authors while at the same time puzzling the scholar with its loose commitment to facts. While it contains summaries of many books that are deserving of celebration and a wider readership, as a comprehensive resource the researcher ought to be wary of its claims.

Eminent Cree author Tomson Highway’s From Oral to Written, released by Talonbooks in 2017, is beautifully flawed, inspiring the reader with tremendous lists of books by Indigenous authors while at the same time puzzling the scholar with its loose commitment to facts. While it contains summaries of many books that are deserving of celebration and a wider readership, as a comprehensive resource the researcher ought to be wary of its claims.

There are several strengths. For theatre researchers, Highway is an amazing source since he served as artistic director with Native Earth Performing Arts in Toronto from 1986 to 1992, and saw first-hand the emergence of this scene. He references over thirty plays, many foundational in the establishment of Indigenous theatre in Canada. Unfortunately, given that scripts are typically used by actors to mount productions or studied in university theatre classes rather than read alone, not all the titles are readily available.

Some, by recognizable names like Drew Hayden Taylor and Marie Clements, can easily be found in libraries and bookstores or, like Floyd Favel’s Lady of Silences (1998) are published as part of anthologies; others are more obscure, such as Jim Morris’s Son of Ayash (1991), which might only be located in the Native Earth Performing Arts archive. Notably absent in this inventory are Highway’s own well-known and frequently taught plays.

Also, anyone looking for titles of Indigenous literature in French will find an impressive list generally unknown in English-speaking circles. For example, while Maria Campbell’s Halfbreed (McClelland & Stewart, 1973), is both widely-read and influential, Highway reminds us that published at about the same time is an autobiography by Innu writer An Antane Kapesh (Anne André) called Je suis une maudite sauvagesse (Leméac, 1976).

More than forty years later, this important text is about to come out in English in the first time. Literature professor Sarah Henzi is working with Kapesh’s community to release a new translation in early 2019. What makes this text intriguing is that it has existed in bilingual form since 1976: while Kapesh wrote it in Innu, it was almost immediately translated into French. Highway reflects that “one gets the impression that it was written first in Innu and then translated by the author” (p. 330). However, this is not correct. The copyright page of the first edition identifies the translator as José Mailhot.

More than forty years later, this important text is about to come out in English in the first time. Literature professor Sarah Henzi is working with Kapesh’s community to release a new translation in early 2019. What makes this text intriguing is that it has existed in bilingual form since 1976: while Kapesh wrote it in Innu, it was almost immediately translated into French. Highway reflects that “one gets the impression that it was written first in Innu and then translated by the author” (p. 330). However, this is not correct. The copyright page of the first edition identifies the translator as José Mailhot.

It might be that for complaints such as mine, Highway has included a note to follow his problematic introductory essay. He writes that “[t]his is not an academic book. I am not an academic. I don’t use academic language. I am an artist. I use artistic language” (p. xxxiii). This is an odd statement to make at the beginning of what is essentially a reference text that scholars will be pleased to consult. It does not excuse him for ascribing dates with little grounding in historical analysis.

And while the book’s subtitle is “A Celebration of Indigenous Literature in Canada, 1980-2010,” it remains to be seen if there is any good reason to stop at 2010, besides the need to stop at some date. He asserts that, “that first wave started only with the big explosion that happened in and around the year 1980. This is when Indigenous literature in Canada became a genuine movement, a genuine wave, a genuine phenomenon.…” (p. xii).

But if you search the 175 titles that Highway lists, none are published in 1980, 1981, or even 1982. It is not until 1983 that In Search of April Raintree (Pemmican Publications) by Beatrice Culleton (now Mosionier) appears, and then nothing in 1984. My point is not to quibble about categories but rather to warn the reader not to rely on the historical accuracy of Highway’s claims.

But if you search the 175 titles that Highway lists, none are published in 1980, 1981, or even 1982. It is not until 1983 that In Search of April Raintree (Pemmican Publications) by Beatrice Culleton (now Mosionier) appears, and then nothing in 1984. My point is not to quibble about categories but rather to warn the reader not to rely on the historical accuracy of Highway’s claims.

Likewise, other claims in his opening essay are not supported. When Highway calls 1960, when Status Indians were given the right to vote in federal elections, a watershed year because it was “legal for [First Nations people] to leave the reserve and migrate to cities…” (p. xix), he promotes misunderstandings about the complicated history of the Pass system.

Canada never actually had the legal ability to confine Status Indians to reserves, although it did so illegally and coercively up until the mid-1940s. The idea, that in 1960 the gates from reserves to the City were unlocked so that its residents could move, is incorrect. Instead, the North America-wide shift to urban areas after the Second World War is also part of the reason Indigenous people flocked to the cities. As well, analysis of the loss of status by generations of First Nations women and their children, and the loss of their right to live on reserve upon marriage (and even after marriage break-up) to non-Status men, would provide a balanced understanding of Indigenous movement to urban spaces.

Highway also describes at length the horror of the “classic image of the drunken Indian” (p. xxi), and suggests that Indigenous people have a genetic vulnerability to alcohol. I encourage readers to question this claim when trauma, poverty, the undermining of cultural supports, and the pervasiveness of racism and damaging stereotypes are better explanations than genetic difference.

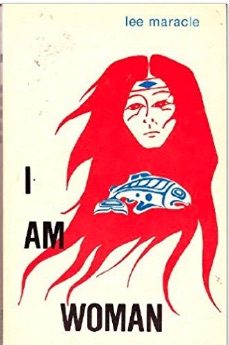

There are a host of other little inaccuracies that betray a lack of interest in book history. Lee Maracle’s remarkable 1988 collection of essays, called I Am Woman (Write-On Press) did not have the accompanying subtitle “A Native Perspective on Sociology and Feminism” until it was re-issued by another publisher in 1996.

There are a host of other little inaccuracies that betray a lack of interest in book history. Lee Maracle’s remarkable 1988 collection of essays, called I Am Woman (Write-On Press) did not have the accompanying subtitle “A Native Perspective on Sociology and Feminism” until it was re-issued by another publisher in 1996.

Robert Alexie’s Porcupines and China Dolls might have been originally published in 2002 (Stoddart), but its distribution was significantly interrupted by the fact that Stoddart immediately went bankrupt. Theytus Books re-released it in 2009.

What is also vexing to me, as an Indigenous scholar, is the title itself, From Oral to Written, which might of course be the decision of the publishing house rather than the author. Even as I try in my own work to break the assumptions around the oral and the written as opposites, and to remember that both are part of a multimodal communicative practice, this book reinforces them as opposite forms of creative expression. As part of this, I regularly urge my students to avoid assuming a history for Indigenous narrative production that resembles the supposed “progress” narrative of Western literature from oral forms, such as stories or epic poems, through to the novel.

This understanding of history as progress from the oral to the written is really the superimposition of the supposed progress from the savage to the civilized, and I remind my students whom that analysis typically benefits.

Therefore, rather than adopt Western categories, I encourage students to enlarge the definition of literacies that can hold Indigenous philosophies, ways of knowing, and storytelling in a variety of forms that include ones told verbally (like story cycles, hip hop, nursery rhymes, lectures, invocations); physically (dance, video games, ceremony with drumming and singing); through to writing (like short stories, petroglyphs, novels, winter counts, beading, graphic novels, carving).

Therefore I am ideologically opposed to this book’s cover blurb that describes “the Indigenous literary tradition established by a brave, committed, hard-working, and inspired group of exceptional individuals.…” Indigenous literary traditions are not the invention of a recent generation of clever published writers, but rather a continuation of Indigenous understandings of story in its multiple forms from Time Immemorial.

Indigenous storytellers and writers have always adapted to constantly changing circumstances, and in the process have adopted a myriad of methods to tell our stories. And we will continue to do so.

*

Deanna Reder (Métis) is Chair of the Department of First Nations Studies and Director of the Master of Arts for Teachers of English program in the Department of English at Simon Fraser University. She is Principal Investigator on a five-year Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council (SSHRC)-funded project called “The People and the Text: Indigenous Writing in Northern North America up to 1992.” She is the Past-President of the Indigenous Literary Studies Association and the Series Editor for the Indigenous Studies Series at Wilfrid Laurier University Press. She has co-edited four books: two with Linda Morra, Troubling Tricksters (2010) and Learn, Teach, Challenge: Approaching Indigenous Literatures (2016); the third with Sophie McCall and co-editors David Gaertner and Gabrielle Hill, Read, Listen, Tell: Indigenous Stories from Turtle Island (2017) — all with WLU Press; her final book is with Algonquin scholar Michelle Coupal, Métis poet Joanne Arnott, and Secwepemc-Ktunaxa educator Emalene Manuel, Honouring the Strength of Indian Women: Plays, Stories, Poetry by Vera Manuel (forthcoming, University of Manitoba Press, 2018).

*

The Ormsby Review. More Readers. More Reviews. More Often.

Reviews Editor: Richard Mackie

Reviews Publisher: Alan Twigg

The Ormsby Review is a journal service for serious coverage of B.C. books and authors, hosted by Simon Fraser University. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Robin Fisher, Cole Harris, Wade Davis, Hugh Johnston, Patricia Roy, David Stouck, and Graeme Wynn. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk.

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

Leave a Reply