#9 David Thompson

David Thompson’s cartography, his endurance, his consistent respect for Aboriginal peoples, his pathfinding, his versatility in at least six languages and his prodigious literary legacy qualify him as the most under-celebrated hero in Canadian history.

August 10th, 2015

This statue of Thompson and his First Nations wife Charlotte Small has been erected in Invermere.

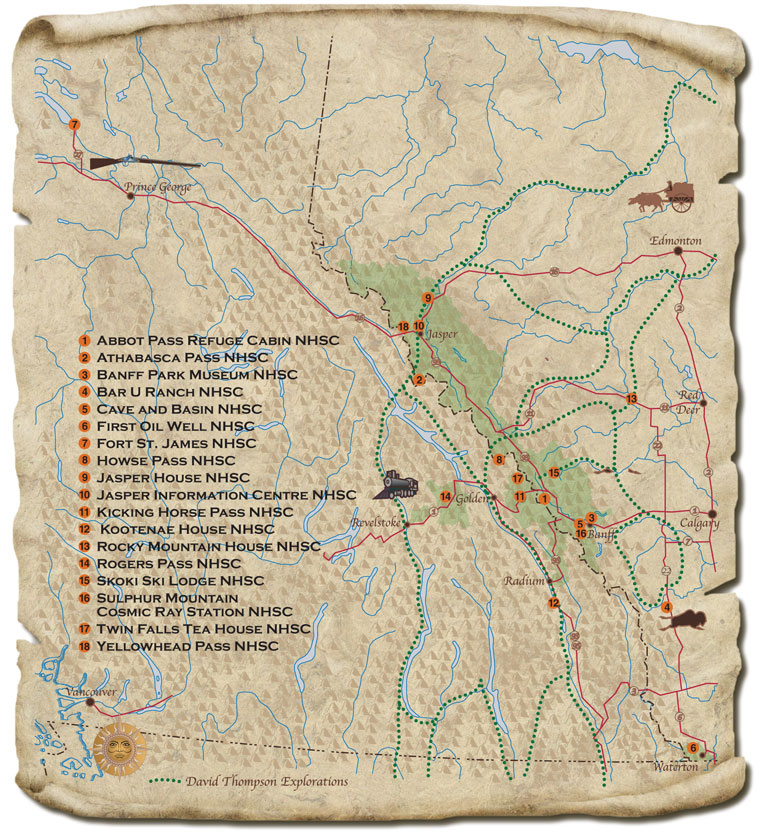

LOCATION: Howse Pass. Here David Thompson first crossed into territory that is now part of present-day B.C. Thompson traversed Howse Pass in 1807 and established Kootenae House in the Columbia River Valley. Howse Pass was declared a national historic site in 1978.

DIRECTIONS: 51°48′ N 116°45′ W. Located between Mount Conway and Howse Peak, the pass can only be reached by hiking 26 km west from the Icefields Parkway (Highway 93 North).

David Thompson’s writing deserves blaring trumpets.

The second in a planned three volumes of David Thompson’s writings, The Writings of David Thompson, Volume 2: The Travels, 1848 Version and Associated Texts (McGill-Queens 2015) completes the great surveyor and fur trader’s spirited autobiographical narrative. Thompson describes his most enduring historical legacy – the extension of the fur trade across the Continental Divide between 1807 and 1812.

During these years Thompson established several Nor’wester trading posts, made contact with the tribal peoples of the Columbia Plateau, and tirelessly mapped the lands he traversed, all the time striving westward toward the Pacific. The tale culminates with Thompson’s historic arrival at the mouth of the Columbia in July 1811.Like its companion Volume 1, this work presents an entirely new transcription by William Moreau of Thompson’s manuscript, and is accompanied by an introductory essay placing the author in his historical and intellectual context.

The following excerpts from The Writings of David Thompson, Volume 2: The Travels, 1848 Version and Associated Texts (McGill-Queens $44.95, 978-0-7735-4551-9, edited by William E. Moreau) present some of Thompson’s so-called “dining experiences” in the Western Interior, including an early description of maple syrup production.

The following excerpts from The Writings of David Thompson, Volume 2: The Travels, 1848 Version and Associated Texts (McGill-Queens $44.95, 978-0-7735-4551-9, edited by William E. Moreau) present some of Thompson’s so-called “dining experiences” in the Western Interior, including an early description of maple syrup production.

—

“Where we came on the Red Lake, a fine sheet of water, was in Latitude 47°58’15” North Longitude 95°35″37′ West, by observation. Here we came to six Tents of Indians, with the good old Chief the Sugar, he gave us two pickerel and three fine pike fish. They had no canoe, and requested the loan of mine to spear fish in the night, by which, very many Indians usually maintain their families: the darker the night, the better; a quantity of Birch Rind is collected, and loosely tied in small parcels this substance always burns with a brilliant light, but of short duration; therefore several parcels are made ready, the spear man is in the bow of the canoe, close behind him is a pole of about four feet above his head to which is attached the lighted flaming Birch Rind, by which he sees clearly into the water, by a person in the stern, the canoe is moved along quietly and silently, the approach of the flaming light, appears to stupify the fish, they are always speared in a quies[c]ent state; as if unable to move away; they speared three large sturgeon, each averageing about sixty pounds, of which they gave us one; this has always appeared to me, a strange fish, if I might be allowed, I should call it the fresh water Hog; in shoal muddy Lakes, it is one of the finest fish that can be eaten but in clear rivers like the St Lawrence, the sturgeon is a hard tasteless fish: in the turbid waters of the Columbia River, near the Pacific Ocean, this noble fish is from three to seven hundred pounds in weight, and as rich in nourishment as the best beef; April 19th. Killed a Crane, a goose, and a duck, all fat, but as I have already remarked the broth of the Crane is much better than any other bird.

(…)

“The sinuousities of the upper part of the Mississippe I found to be beyond my belief; from the South West corner of the Turtle Lake, is a Brook of three yards in width, by two feet in depth, at 2½ miles per hour, but so devious it’s course, we preferred carrying 180 yards to a small Lake, which sends a Brook into it, taking my courses and distances by points of Woods, we descended 24 miles to the Red Cedar Lake but by the river the distance is three times this length; in this distance we carried at three falls; and the River entered the Lake fifteen yards wide, by two feet deep, at 2¼ miles per hour having received several fine Brooks. The country all this distance is entirely changed to low grassy lands tending to marsh, Woods of Maple Plane, Ash, Larch, Birch, Red and white Cedar; Water Fowl of all kinds in plenty; and the wild rice in abundance, on which the water fowl feed, and become fat, and very fine eating, but are also very wild, and are killed on the wing. Although a first rate shot, four to six ducks a day, was an average. There was much ice in the Red Cedar Lake, which gave us hard labor to get along, having proceeded five miles we came to the house of Mr John Sayer a partner of the North West Company; the people of this place had passed the whole winter on wild rice, it is a very weak food, and though fowl fatten on it, yet it barely keeps mankind alive; but those who live upon it, however poor in flesh, are healthy, as we came loaded with the ducks I had shot we were very welcome.

“The sinuousities of the upper part of the Mississippe I found to be beyond my belief; from the South West corner of the Turtle Lake, is a Brook of three yards in width, by two feet in depth, at 2½ miles per hour, but so devious it’s course, we preferred carrying 180 yards to a small Lake, which sends a Brook into it, taking my courses and distances by points of Woods, we descended 24 miles to the Red Cedar Lake but by the river the distance is three times this length; in this distance we carried at three falls; and the River entered the Lake fifteen yards wide, by two feet deep, at 2¼ miles per hour having received several fine Brooks. The country all this distance is entirely changed to low grassy lands tending to marsh, Woods of Maple Plane, Ash, Larch, Birch, Red and white Cedar; Water Fowl of all kinds in plenty; and the wild rice in abundance, on which the water fowl feed, and become fat, and very fine eating, but are also very wild, and are killed on the wing. Although a first rate shot, four to six ducks a day, was an average. There was much ice in the Red Cedar Lake, which gave us hard labor to get along, having proceeded five miles we came to the house of Mr John Sayer a partner of the North West Company; the people of this place had passed the whole winter on wild rice, it is a very weak food, and though fowl fatten on it, yet it barely keeps mankind alive; but those who live upon it, however poor in flesh, are healthy, as we came loaded with the ducks I had shot we were very welcome.

“There is something curious in the state of the stomach of a person, who has always lived on Meat, and of a sudden attempts to change to vegetable food; this we found; we left Mr Sayer with wild rice and maple sugar for our provisions; and enjoyed the change; but on the third day heart burn and weakness of the stomach came on us, and we had to take to hunting and fishing to relieve us, which two meals of animal food effected. A great staple of these countries is the Sugar made from the Maple Trees by incisions made with an axe in the form of a sloping notch, at the lower end of which a chip is inserted to make the sap run off, clear of the tree into vessels of wood, or birch rind, placed on the ground to receive it. During the spring all the Indians employ themselves in collecting the sap and boiling it into sugar, which they make to imetate the muscovado’s of the West Indies, this is done, when the sap is brought to a proper consistence by stirring it quickly with a very small paddle until it is cool. The sugar of the hard maple tree is of a fine brown color, that of the Plane Tree, called soft Maple, is of a light color, like the East India sugar, but is not so sweet as the sugar of the hard Maple. The Indians quietly parcel out the maple groves to each family, and which is kept in the family, but what is not thus occupied, and this is of great extent, is open to any person. Of these sugars great quantities were made, of which the north west company bought many tons weight, it’s price is much the same as the common muscovado sugar.”

—

Here follows an extensive introduction to David Thompson’s life and work by Alan Twigg of B.C. BookWorld:

Born in London, England, on April 30, 1770, David Thompson was the son of parents with Welsh heritage, but he can’t properly be described as a Welshman. “In David Thompson’s letters and manuscripts,” says Victor Hopwood, a leading authority on Thompson’s writing, “I found nothing about Wales or the Welsh, nothing to indicate he ever thought of himself as Welsh.”

David Thompson’s father was buried in a pauper’s grave before David Thompson turned three. At age seven he was accepted into London’s Grey Coat School, a charity institution near Westminster Abbey for both boys and girls of “piety and virtue.” There he excelled at spelling, penmanship, mathematics, navigation and literature. Books such as Robinson Crusoe, Gulliver’s Travels and Tales of the Arabian Nights kindled his spirit for adventure.

In 1784, at age fourteen, Thompson gained a position with the Hudson’s Bay Company as an indentured apprentice after his school paid the Honourable Company five pounds to accept him. Having been given a Hadley’s quadrant and a copy of Robertson’s two-volume Elements of Navigation as graduation gifts, Thompson sailed on the HBC ship Prince Rupert, stopped at Stromness on the Orkney Islands as the last port of call, and arrived in Rupert’s Land for his seven-year apprenticeship.

He arrived in the New World, at Fort Churchill on Hudson Bay, on September 1, 1784, and was at first disappointed by his limited responsibilities. At Fort Churchill, as well as at York Factory, 150 miles to the south, Thompson discovered, “. . . neither writing or reading was required. And my only business was to amuse myself, in winter growling at the cold and in the open season, shooting Gulls, Ducks, Plover and Curlews, and quarrelling with Musketoes [mosquitoes] and Sand Flies.”

During this period, he copied some of Samuel Hearne’s journals of exploration and took advantage of Joseph Colen’s impressive library at York Factory, containing 1400 volumes. He also bought his own copies of Milton’s Paradise Lost and Samuel Johnson’s Rambler.

Transferred to forts on the Saskatchewan River, Thompson was introduced to the birchbark canoe in 1786 and passed the winter of 1787 with Peigan Indians, learning their language and customs. He later observed: “Writers on the Indians always compare them with themselves, who are all white men of education. This is not fair. Their noted stoic apathy is more assumed than real. In public, the Indian wishes it to appear that nothing affects him. But in private, he feels and expresses himself sensitive to everything that happens to him or his family. On becoming acquainted with the Indians I found almost every character in civilized society can be traced to them—from the gravity of a judge to a merry jester, from open-hearted generosity to the avaricious miser.”

When Thompson broke his leg in an accident two days before Christmas in 1788, the injury turned out to be fortuitous. Months later, as an invalid, he was sent on a sleigh to Cumberland House where he was able to further his aptitude for surveying and astronomy by studying with the cartographer and “practical astronomer” Philip Turnor. Using a sextant, a compass, thermometers, watches and a Nautical Almanac, Thompson was able to survey most of northern Manitoba and Saskatchewan for his employers between 1792 and 1796. Although he was rewarded with pay increases and promoted, Thompson felt his employers did not fully grasp his potential.

Feeling under-employed by the HBC, Thompson accepted an offer to work for the rival North West Company in 1797. In the aftermath of the Treaty of Paris in 1783, the NWC needed someone to tell them whether their existing forts lay within the boundaries of Canada or the United States. Having been promised map paper and a new set of drawing instruments, Thompson, at age twenty-eight, proceeded to travel more than four thousand miles in his first year with the NWC, mapping the locations of their various posts.

In 1797, Thompson discovered the source of the Mississippi River was Turtle Lake and predicted the Anglo-Saxon population of North America would eventually “far exceed the Egyptians in all the arts of civilized life.” Usually accompanied by French-Canadian voyageurs, he roamed from the Missouri and Mississippi Rivers to Sault Ste. Marie and back to Grand Portage. Early in 1798 he first met “Mountain Indians” who piqued his interest in the largely unexplored territories of the Rocky Mountains.

While on the prairies, David Thompson met his mixed-blood wife of 57 years, fourteen-year-old Charlotte Small, daughter of the Irish-born trader Patrick Small. According to historian Jennifer Brown, the union between Charlotte Small and David Thompson was the longest documented pre-confederation fur trade marriage in Canada. Charlotte’s father had retired from the North West Company and returned to live in Great Britain when she was five. The couple was married in the country fashion (au facon du nord or au facon du pays) on June 10, 1799, at Île-à-la-Crosse (in present-day Saskatchewan) and had the first of their 13 children at Rocky Mountain House, a cluster of cabins in the foothills of Alberta, on the North Saskatchewan River near the Clearwater River, in 1801. Ten of their children would survive into adulthood.

While stationed at Rocky Mountain House in the winter of 1800, Thompson made his first contacts with Kootenai Aboriginals who had ventured east of the Rockies to trade, despite their fears of the hostile Peigans. “I cannot help admiring the Spirit of these brave, undaunted, but poor Kootenaes,” he recalled. Aware the Peigans were notorious horse thieves who wished to retain their superiority as middle-men between the Kootenaes and the white traders, Thompson befriended the mild-mannered Kootenais and gained their trust in spite of animosities from the Peigans.

The location of Howse Pass where David Thompson reached the present-day British Columbia border is marked by #8.

Taking along his wife, their three children and ten packhorses that bore 300 pounds of pemmican, Thompson reached the Columbia River near Golden, B.C., via Howse Pass, located southwest of Rocky Mountain House, in 1807. (According to Victor Hopwood, Howse Pass was not named by Thompson on his 1814 map in honour of North West Company trader Jasper Hawes, who manned a supply depot at Brûlé Lake, on the Athabasca River, built in 1813. Nor was it named by Thompson for his rival Hudson’s Bay Company trader, Joseph Howse, who followed Thompson over the pass and took one of the first Hudson’s Bay parties onto the Pacific Slope in 1810.)

At Howse Pass, Thompson reportedly allowed one of his horses to destroy two kegs of alcohol for trading. This account might be less than credible. “I had made it a law unto myself,” Thompson later recalled, “that no alcohol should pass the Mountains in my company…. I wrote my partners what I had done; and that I should do the same to every keg of alcohol. And for the next six years that I had charge of the fur trade on the West side of the Mountains, no further attempts were made to introduce spirituous liquors.”

Whereas the Hudson Bay Company tended to distribute raw gin tinctured with molasses, calling it “English brandy,” the Nor’Westers mostly traded with diluted raw alcohol called “licker.” Frank Rasky claims in The Taming of the Canadian West that “…where [Simon] Fraser patronized the Indians, Thompson loved them. He was the only Nor’Wester trader who refused to debauch them with rum.” This statement is an exaggeration given that Thompson frequently dispensed alcohol to Aboriginals, in keeping with corporate policies, prior to 1807.

During Thompson’s inaugural excursion into present-day British Columbia, one of his voyageurs, Beaulieu (“a clever active man”), took ill in May after their party was forced to butcher one of their dogs for food. The dog had been speared by a porcupine and the unfortunate Beaulieu, having eaten heartily, had ingested a porcupine quill. When Beaulieu took ill, Thompson found the end of the black quill had punctured Beaulieu between his ribs. Thompson recalled: “enlarging the place with a lancet, and applying a pair of pincers, I drew it out; and the pain ceased.”

By June 22, Thompson saw the mighty Columbia River and prayed to God that he would one day see where it reached the ocean. That summer Thompson and Beaulieu established Kootenai House at Lake Windermere and the following winter they endured a three-week siege by a 40-man Piegan war party. Before he left the Kootenay region, Thompson named Windermere Lake as Kootenae Lake, and he named the north-flowing river as Kootenai River, not realizing it was the Columbia. He also named a mountain range after Admiral Horatio Nelson who had died two years earlier at the Battle of Trafalgar.

In the spring of 1808, while exploring the Kootenay and Moyie Rivers, Thompson became aware the Columbia River he sought was only approximately fifty miles to the west, but the poor condition of his men and horses prevented him reaching it. Only the reliable advice of his guide Ugly Head enabled Thompson to reunite with Charlotte and his children, thereafter returning to Rocky Mountain House in late June.

By 1809, John Jacob Astor was openly planning to build a fort for the Pacific Fur Company at the mouth of the Columbia. In return for offering the NWC a one-third interest in his Pacific enterprise, Astor proposed to William McGillivray that he grant him a half-share in their Great Lakes enterprise. McGillivray gave his tentative assent to the deal during a visit to New York in early 1810 but stalled the American by saying any such contract would have to be confirmed by his wintering partners during their annual Fort William gathering. These directors of the NWC were not able to accept Astor’s offer until July of 1810 by which time McGillivray and his colleagues in Montreal had conceived a preventative measure.

The NWC sent an urgent message to David Thompson to hasten to the mouth of the Columbia River in advance of Astor’s settlement party who were intending to round the Horn in a ship called the Tonquin.

A Columbia brigade of four canoes, dispatched by Thompson along the Saskatchewan River in early September, reached Rocky Mountain House by late September. While Thompson was hunting for fresh provisions, his main Columbia-bound contingent was forewarned by a Peigan chief named Black Bear to proceed through Howse Pass at their peril. According to Black Bear, the Peigans were setting up a blockade to prevent the voyageurs from having further contact with the so-called Flat Heads (Kootenai). The voyageurs watched and waited, then opted to return to Rocky Mountain House.

Aware that the hostility of Blackfeet tribes could not be taken lightly, Thompson respected his men’s decision. Rather than resort to violence or attempt to bribe the Peigans, he would attempt a detour on an untried route to the north, near the headwaters of the Athabasca River.

While Alexander Henry successfully diverted the attention of the Peigans with copious amounts of rum, Thompson’s Columbia brigade was re-commenced with a long and arduous traverse between the Saskatchewan and Athabasca Rivers. Meanwhile news reached Rocky Mountain House that Hudson’s Bay Company traders had been similarly stymied by fearsome Peigans near Canal Flats.

Attempting to cross the Rocky Mountains in December and January, using an unknown route, soon took its toll on morale. Even Thompson privately confided in a letter written on December 21, “I am getting tired of such constant hard journeys; for the last 20 months I have spent only barely two months under the shelter of a hut, all the rest has been in my tent, and there is little likelihood the next 12 months will be much otherwise.”

By the end of the year, Thompson’s party, guided by an Iroquois named Thomas, was reduced to twelve men, four horses and eight dogs. Trudging on snowshoes through uncharted territory, enduring temperatures that dipped to 26°-below-zero, Thompson managed to discover Athabasca Pass, the main route westward for British traders thereafter, but his horses could not accompany them in the deep snow.

Reaching the crest of the pass, Thompson sent one of his voyageurs and the guide Thomas back with messages for William Henry, his NWC partner. Dogs and men floundered and faltered. “The courage of part of my men,” wrote Thompson, “. . . sinking fast . . . . when Men arrive in a strange Country, fear gathers on them from every Object.”

After his party descended a 2,000-foot-glacier, three disheartened voyageurs essentially deserted, taking with them a companion who was snow-blind. Thompson and his two remaining able-bodied men, Vallade and L’Amoureux, built a twelve-by-twelve foot hut at a place to be called Boat Encampment. After his men Pareil and Coté returned with a Cree hunter and an additional voyageur, Thompson set his mind to improvising a 25-foot canoe to be built from cedar trees, binding the planks with pine roots. It took him much of the month of March to succeed.

After some harrowing paddling and a series of portages, Thompson was able to descend the turbulent Kootenay River, buy horses at Kettle Falls, acquire four Aboriginal paddlers and a new canoe, and begin his descent of the Columbia. Stopping to befriend the Shahaptin Indians in eastern Washington, Thompson was embarrassed to watch a dance in which the women were naked. However, unlike most traders, he was not repelled by their different ways of living.

“The women would pass for handsome,” he wrote, “if better-dressed. But they were all as cleanly as people can be without the use of soap—an article not half so much valued in civilized life as it ought to be. What would become of the beau and belle without it? Take soap from the boasted cleanliness of the civilized man, and he will not be as cleanly as the savage, who never knows its use.”

Prior to reaching the mouth of the Columbia River, Thompson raised a Union Jack on July 9, 1811, and affixed a piece of paper on which he claimed the territory for Britain. “The N.W. Company of Merchants from Canada do hereby intend to erect a factory in this place for the commerce of the country around,” he wrote.

But he was too late. On July 15, Thompson discovered John Jacob Astor’s hired crew of former Nor’Westers had already reached the mouth of the Columbia River in March and built four log cabins at the river’s mouth. This was to be Astoria, located not far from where Lewis & Clark had built their temporary Fort Clatsop some six years earlier. It would be augmented by the arrival on February 15, 1812, of an overland expedition of Astorians led by Wilson Price Hunt, having travelled for nineteen-and-a-half months from Montreal.

David Thompson’s arrival was witnessed and recorded by both Alexander Ross and Gabriel Franchère. The latter noted: “Mr. Thompson had kept a regular journal and had traveled, it seemed to me, more like a geographer than a fur trader.” Franchère was correct. With his sextant always at hand, David Thompson, along with eight Iroquois and voyageurs, and an interpreter, descended most of the Columbia River and proved it was a navigable route through the Rocky Mountains to the Pacific.

“The trail by which Thompson crossed the Rockies at this time,” Victor G. Hopwood has noted, “later became the historic trail of the Columbia fur trade, from Jasper House on the Athabasca River to Boat Encampment at the Big Bend of the Columbia River. Its adoption first by the North West Company and later by the Hudson’s Bay Company was a tacit admission of the rightness of Thompson’s earlier contention that a new trail should be found to replace the Howse Pass route across the mountains.”

Thompson and his men were duly feted by the Astorians who understood he had opened the way for a thriving new fur trade on the Pacific Slope.

Thompson’s alleged “failure” to reach the mouth of the Columbia River prior to the Astorians has been criticized by some Anglophiles as cowardice in the face of hostilities from Peigans who were restricting his access to Howse Pass. Helen and George Akrigg, in particular, have dubbed Thompson the “Hamlet” of the fur trade because he was not always as decisive in his movements as he might have been.

Such retrospective charges absurdly fail to appreciate that David Thompson, among all the fur traders, was the only person who was taking in everything as he went—humanity, geography, natural science and astronomy. Unlike Alexander Mackenzie and Simon Fraser, whose motivations were strictly commercial, Thompson was not ruthless. Often laden with furs, Thompson was thoroughly curious and concerned with maintaining civil relations with all he met. He recorded birds and weather and topography and foreign words and events in the heavens, evidently in search of knowledge as much as fame. “To ascertain the height of the Rocky Mountains above the level of the Ocean,” he wrote, “had long occupied my attention.”

It is difficult to imagine another fur trader observing, “no dove is more meek than the white grouse. I have often taken them from under the net, and provoked them all I could without injuring them, but all was submissive meekness, rough beings as we were, sometimes of an evening we could not help enquiring why such an angelic bird should be doomed to be the suffering prey of every carnivorous animal, the ways of Providence are unknown to us.”

As a transcriber of Aboriginal myths, Thompson has been admired by the likes of poet A.J.M. Smith for his “almost Homeric freshness of vision.” Rather than impose his own prejudices onto others, he made compromises with the First Nations he encountered. Bullying was not his way. His business enterprises in Ontario would later fail because he was reluctant to be aggressive in demanding monies owed to him.

Thompson grasped how the coming of the white man was drastically altering the natural order in the North American wilderness, eliminating the beaver and other animals, and degrading Aboriginal societies. Intensely self-aware, Thompson also explored his own philosophical nature by maintaining his journal writing until he reached age eighty—for twenty-two years in the West and another thirty-eight years in eastern Canada.

Upon moving his family to eastern Canada in 1812, David Thompson solemnized his marriage to Charlotte as soon as possible.

While serving as an ensign in the Sedentary Militia during the war of 1812-1814, Thompson set about making one great map that showed all of the Northwest Territory of Canada. More than ten feet long, it would take Thompson more than two years to produce, locating 78 NWC trading posts and encompassing the approximately one-and-a-half million square miles David Thompson had travelled. Thompson’s unprecedented map was presented to his former employers and it hung for many years in the dining hall of the NWC headquarters at Fort William on Lake Superior. It remained in use into the next century. This map was published by the NWC in a pamphlet that became the primary source for subsequent maps.

In 1814, Thompson improved upon his first map. A copy of this version was sold by one of his sons to the Upper Canada government and it subsequently served as the basic map of Western Canada for much of the nineteeth century. This second map, in Thompson’s own words, “embraces the Region lying between 45 and 60 degrees North Latitude and 84 and 124 degrees West Latitude comprising the Surveys and Discoveries of 20 years namely the Discovery and Survey of the Oregon Territory to the Pacific Ocean [and] the survey of the Athabasca Lake. Slave River and Lake from which flows Mackenzie River to the Arctic Sea by Mr. Philip Turnor the Route of Sir Alexander Mackenzie in 1782 down part of Frasers River together with the Survey by the late John Stuart of the North West Company.”

Thompson continued to refine his cartography, sending improved maps to Britain in 1826 and 1843. These became the property of the British Museum and the Public Records Office in London. It is seldom noted that David Thompson also drew the map that appeared in Alexander Mackenzie’s Voyages from Montreal, published in 1801, a work that incorporated Thompson’s extensive cartography work up to 1800. Mackenzie rarely, if ever, accorded any credit to others.

David Thompson was never properly recognized or well-paid for his labours. “His employers permitted London cartographers, like the firm of Arrowsmith, to publish his discoveries,” wrote Richard Glover in BC Studies, “—an act which Professor Hopwood describes as ‘pirating.’ This term is hardly correct, for Thompson’s maps were the property of the employers who had paid him to make them. The result was nevertheless unfortunate. It caused the world that used Thompson’s splendid maps to be denied almost all knowledge of their author.”

Following the Treaty of Ghent, Thompson worked for at least ten years (1816-1826) as the British surveyor and astronomer for an international boundary commission that defined the border between Canada and the United States from the St. Lawrence River island of St. Regis to Lake of the Woods, near what is now the Ontario-Manitoba border. He spent his summers mostly in the field and his winters at Williamstown, preparing his maps. When the American-appointed surveyor resigned halfway through this project, he was not replaced. Such was Thompson’s trustworthiness and competence that his work was accepted as correct by both sides.

His work for the Boundary Commission included the difficult task of finding the most north-westerly point of the Lake of the Woods. This work was undertaken after it was discovered a 1755 map by John Mitchell map had erroneously depicted the most northerly reaches of the Mississippi River. Thompson had already made more than a dozen trips through Lake of the Woods, but the exacting process of ensuring Rat Portage (modern-day Kenora, Ontario) lay within Canadian territory took him several more years to complete. This difficult accomplishment has been documented by historian and cartography expert David Malahar who has located some of the cairns that were placed by Thompson around the north-westerly shores of the lake.

When David and Charlotte Thompson purchased their farm and house at Williamstown, Glengarry County, in 1815, they already had five surviving children. Six more were born in the house that was previously occupied by Reverend John Bethune, who had introduced Presbyterianism to Upper Canada. The first of these six, Elizabeth, was born on April 25, 1817; the last of these, Eliza, was born on March 4, 1829.

Family life was hard. The bankruptcy of McGillivray, Thain and Company, which owed Thompson 400 pounds, combined with Thompson’s tendency to forgive the debts of others, placed him in a precarious financial situation. Thompson rented out eight properties, from small lots to 36-hectare farms, but he was unable to meet his own mortgage payments when his tenants were unable to pay their rents in the early 1830s. He also tried operating a general store, a tavern and potash production facilities.

David Thompson was forced to work for twenty years as a private surveyor in Glengarry County, Ontario. His varied assignments in the Muskoka Lakes area, the Eastern Townships near Sherbrooke, along the shores of Lake St. Peter south of Montreal, and along the St. Lawrence River, were extensive but his earnings were slight. His eyesight severely worsened. Thompson was forced to leave Williamstown, bankrupt, with his family, at age sixty-five.

Despite his 28 years in the fur trade, Thompson was eventually forced to sell his sextant and other instruments to buy food for his family. He even pawned his overcoat. After borrowing two shillings and sixpence from a friend, he wrote his final journal entry: “Thank God for this relief.”

David Thompson died poverty-stricken on February 10, 1857, in Longueuil, Quebec. Charlotte Thompson died three months later.

A son-in-law purchased a burial plot on Mount Royal for David and Charlotte Thompson but the site in Section C, Lot 507, remained unmarked until geographer Joseph B. Tyrrell erected a modest monument there in 1927. He also arranged for Thompson’s succinct epitaph on the tombstone: “The greatest practical land geographer that the world has produced.”

David Thompson, the orphaned apprentice from Grey Coat School, mapped the main travel routes for approximately 1,200,000 square miles of Canada and 500,000 square miles in the United States, travelling more than 80,000 miles by foot, canoe and horse. He also traced the Columbia River to its source, established the first Columbia River trading post, surveyed the headwaters of the Mississippi and pioneered the use of Athabasca Pass—to name only a few of his achievements prior to 1813.

Despite such accomplishments, David Thompson’s name is lesser known than that of his contemporaries, Simon Fraser and Alexander Mackenzie.

David and Charlotte Thompson’s home in Williamstown, Ontario, renamed the Bethune-Thompson House, has been preserved as a heritage site, and some of his instruments have been recovered by the Ontario Archives. The Royal Ontario Museum contains one of the two gigantic maps Thompson made for the North West Company to locate accurately the major drainages on both sides of North America north of the forty-fifth parallel. David Thompson Highway #11 connects Red Deer to Rocky Mountain House National Historic Site, but Thompson, Manitoba, is not named in Thompson’s honour. (Instead it is named for INCO chairman John F. Thompson.) Rocky Mountain House has a David Thompson sextant.

The man who earned the nickname “Koo-koo-sint” (meaning “the man who looks at the stars” in the language of Nez Percé Indians) never saw the Thompson River, the longest tributary of the Fraser River, named after him in 1808 by Simon Fraser who mistakenly assumed Thompson must have camped somewhere on its upper waters.

Following the closure of short-lived David Thompson University-College in Nelson, British Columbia, in 1984, the David Thompson Cultural Society continues to organize social and cultural presentations for the Nelson community. On July, 1, 2002, a new statue of David Thompson and Charlotte Small was erected at Invermere, B.C. as a prelude to a series of related bi-centennials pertaining to Thompson to take place in the north-west from 2007 to 2011. In 2005, a David Thompson exhibit at Spokane’s Northwest Museum of Art and Culture opened to present Thompson’s journals, maps, and mountain sketches, along with field sketches by artists Paul Kane and Henry James Warre. Retired BC Land Surveyor Barry Cotton has provided an excellent introductory article, In Search of David Thompson: A Study in Bibliography, in BC Historical News, Vol. 37, No. 4, Fall 2005.

With the advent of the David Thompson 2007 Bicentennial initiatives to commemorate Thompson’s arrival in British Columbia, there was growing agreement that Thompson’s cartography, his endurance, his consistent respect for Aboriginal peoples, his pathfinding, his versatility in at least six languages and his prodigious literary legacy qualify him as the most under-celebrated hero in Canadian history.

No other fur trader spent more time outside forts rather than in them. No other person in the Canadian fur trade was more faithful, diligent and articulate. David Thompson not only opened the route for commerce that would connect both sides of the North American continent, pioneering use of the Columbia River for trade, his cross-continental astronomy and cartography became the basis for depicting the geography of Canada and much of the United States for a half-century.

In the words of Katherine Gordon, in her study of land surveying in British Columbia, Made to Measure, “Thompson laboured over detailed measurements of the lengths of rivers and the heights of mountains he observed, contributing astoundingly accurate information to the burgeoning material available to British cartographers. Unable to use the heavy and bulky marine chronometers available to Vancouver and his ocean-going counterparts, Thompson resorted to the use of a basic watch combined with astronomical observations to determine longitude. His methods were reliable: he painstakingly and repeatedly observed lunar eclipses of Jupiter’s moons, then compared the time difference between observations at his location and at Greenwich. If Jupiter for some reason wasn’t visible, Thompson measured the angle of the moon against two fixed astronomical bodies instead.

“Thompson’s greatest asset was his diligence in recording thousands of observations over the years in his journals, then following them up by physically surveying the ground between his fixed points to fill in the details.”

Thompson’s fame might have been secured if he had been able to edit and publish his 39 journals in his lifetime. Joseph Tyrrell purchased Thompson’s unfinished manuscript and his journals, then provided an edited version of Thompson’s explorations and accomplishments in David Thompson’s Narrative of his Explorations in Western America, 1784-1812, first published in Toronto in 1916.

It is difficult to celebrate Thompson without a portrait. In his 1850 travel book entitled The Shoe and Canoe, British army surgeon and geologist John Jeremiah Bigsby published the following description of Thompson arising from an 1823 canoe trip for the Boundary Commission:

“His figure was short and compact, and his black hair was worn long all round, and cut square, as if by one stroke of the sheers, just above the eyebrows. His complexion was of the gardener’s ruddy brown, while the expression of his deeply furrowed features was friendly and intelligent, but his shortened nose gave him an odd look. His speech betrayed the Welshman, although he left his native hills when very young. I afterwards traveled much with him. He was a very powerful mind and had a singular faculty of picture making.”

Bigsby’s description of Thompson, as well as pictures of Thompson’s 30-year-old grandson, have served as references for a new, imaginary portrait by Alice Saltiel-Marshall of Canmore, Alberta, to coincide with David Thompson Bicentennial celebrations organized from Invermere, B.C. It is an attempt to portray how Thompson might have looked in 1807 when he first crossed Howse Pass, on the Alberta/British Columbia border, and made contact with the Columbia River. Howse Pass has since been touted as a possible highway route to shorten the driving time between Vancouver and Edmonton.

Currently the David Thompson Highway runs from Red Deer through Rocky Mountain House to Saskatchewan River Crossing in Banff National Park where it joins Highway #93 which is the Icefields Parkway, linking Banff and Jasper, Alberta.

[The black & white portrait with this article is an imagined depiction of David Thompson by Bruce McDonald]

[INFORMATION POSTED JANUARY 1, 2016]

I travelled many roads through my life. I worked in the seismic fields and saw lots of areas in Alberta, Saskatchewan and B.C and tiny bits of Manitoba. Now I have seven Grandchildren and they are all boys. And every place I go, David Thompson almost always enters my mind. \’Was he here?\’ and just about everywhere I travel, he has. Either on foot or on horseback. He walked or rode a horse and did way more than I ever did. Over and over again. Motivation and drive and he mapped wherever I travelled.

What an awesome read..thankyou for posting this..David Thompson is a hero of mine..Typical adventurer,doing what he loved with an observant eye..with very little pay or reward..documenting it along the way..

David Thompson has always been one of my Canadian heroes…as he had many talents in different areas. At school he was praised for his accuracy in mapping or his bravery and survival skills in the wilderness. When older and I read his own descriptions, I marvelled at his use of words in engaging details as well as his intelligence and compassion for all life – all peoples!

Loved this. I think of him all over the landscape,whenever I travel through these western lands, on the river his friend named for him (though he never saw it), in Rocky Mountain House where one has a sense of what he saw — the mountains, the wild waters, the ice fields (though diminished).