#554 Patricia’s preternatural powers

May 28th, 2019

Amateurs at Love

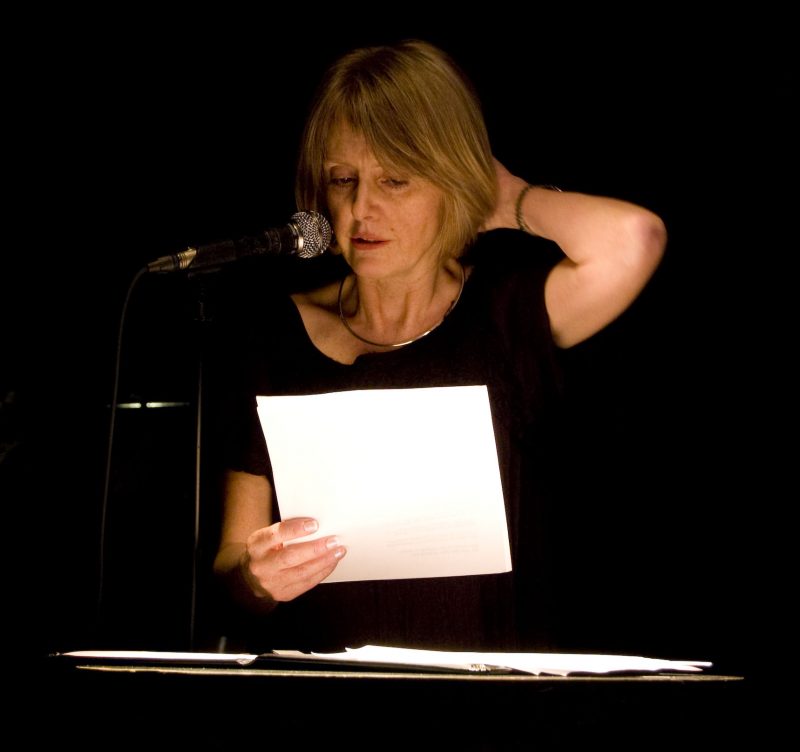

by Patricia Young

Fredericton: Goose Lane Editions, 2019

$19.95 / 9780864929914

Reviewed by Heidi Greco

*

The word “amateur” comes from the French, the source language for our most beautiful words. Originally it meant “one who loves” or “lover” — so, to be an “amateur at love” must mean someone who loves the very idea of love. At least that’s how I’m understanding it, especially now that I’ve read this gorgeous book, one that’s practically brimming over with love. Whether this is love of family members (husband and children and beyond) or a broader one — love of the world, specifically of animals or even of words — it’s an expansive love, expressed in fresh and sometimes surreal ways.

The word “amateur” comes from the French, the source language for our most beautiful words. Originally it meant “one who loves” or “lover” — so, to be an “amateur at love” must mean someone who loves the very idea of love. At least that’s how I’m understanding it, especially now that I’ve read this gorgeous book, one that’s practically brimming over with love. Whether this is love of family members (husband and children and beyond) or a broader one — love of the world, specifically of animals or even of words — it’s an expansive love, expressed in fresh and sometimes surreal ways.

When it comes to using words, Patricia Young is a Mage — or, if we need to put a gendered name on that, she might be called a Sorceress. She spins stories in tightly knit prose poems, plays games with poetic forms, and just about always manages to make it work. Unless her writings are all strictly imaginative, I almost suspect her of preternatural powers. I picture her stirring potions, adding nettles she’s collected, reminiscent of the princess in Hans Christian Andersen’s The Wild Swans, the girl who had to weave cloaks from nettles to restore her beloved brothers, princes who’d been enchanted and turned into birds.

Her familial connections — at least as they’re evidenced in these poems — seem as deep as the ties felt by that fairy tale princess. In a poem called “Son” (more than one poem bears this title), she describes how her son and his adolescent friend clear a space on the living room floor, “With the single-mindedness of furniture movers,” so they can wrestle, with “arm chokes and leg locks.” Once finished, they rearrange the furniture and make snacks that they wolf down before running “out the door, skateboards flying off curbs and plywood ramps.” She, the mother, lingers “on the threshold between one room and another,” a space where it’s clear she understands these boys exist in a land somewhere between being children and men. Her observation of their play suggests the intensity of the male-on-male wrestling in Lawrence’s Women in Love and melts my heart every time I read it: “I watched two boys grapple on a faded carpet with such ferocity they might have been falling into love’s wild and tender death grip.”

Occasional references remind us that Young lives in Victoria, as in a piece called “Husband” which seems to be a (re)creation of meeting him: “I found myself at a kitchen party on the other side of the blue bridge talking to a boy in red cowboy boots.” The blue bridge may no longer be there, having been replaced by an imposing metal structure that roused reaction from more than those simply nostalgic for the old one, but happily enough, the husband remains.

Other poems range further afield, with a suite of poems from Spain, its section header a quote from another Victoria poet, Patrick Friesen, “Spain is a state of mind.” The poems here display Young’s skill at handling some tricky poetic forms, especially the palindrome, which she manages to bend to her own will, making it her own.

Menorca #1

My husband and son are up to their necks

in the Mediterranean. First,

something about me. I am not wind-driven,

but the smell of ancient clay

is lodged in my brain. Any moment now

Odysseus et al. could sail around the corner….

The poem carries on for another dozen or so stanzas before ending with the following lines of reflective closure:

Could Odysseus et al. sail around the corner

any moment now? Lodged in my brain

is the smell of ancient clay.

I am not wind-driven but something about me

is Mediterranean. First –

my husband and son . . . up to their necks

And the Spain section isn’t the only place where Young plays with form. She’s brave enough to have tried her hand at what she calls “Pangramic Love Songs” — and a pangram, for anyone who may have forgotten handwriting practice, is a sentence containing all 26 letters of the alphabet, the most well-known being The quick brown fox jumps over the lazy dog.

These poems see her not only building the words from these sentences into poems, but using those words in the order in which they appear in the original pangram, as in this opening couplet for the sentence/title Quick Zephyrs Blow, Vexing Daft Jim.

Quick! Morning kisses, mint tea, a swim across the lake,

gentle zephyr’s wind: tail end of a hurricane. Blow

Although these poems get high praise on the cleverness scale, I found this the weakest part of the book. After all, how many times can you hear “quick” before realizing it’s simply one of those words that efficiently uses a few hard-to-place letters (think Scrabble): Q, C, and K. Still, I can’t think of any other poet who could have done anywhere near as well with such a daunting challenge.

The cover art, a person in the style of a child’s drawing, clinging to a heart shape which appears to be rising like a helium balloon, catches my eye and charms me all at once. Victoria’s current poet laureate, John Barton, is responsible for the truncated blurb which appears beside the cover image. He warns readers to “Be careful, or this barnyard of miracles will embrace you.” My only quibble with the remark is that Young gives readers more than a mere barnyard of miracles.

I’m thinking not only of her magical treatment of critters in the section called “Animal Tales” with its tightly-wound prose poems that focus on animals from Cow to Lamb to Pig and even Donkey. And please, don’t think for a moment that these are your usual barnyard inhabitants. The cow here has started telling lies. The lamb transcends time, leaving his home for several years, but remains a lamb — returning only to find his mother and the shepherdess locked in the same wrestling match they’ve endured forever. The pig flies; the donkey’s fate is even stranger, multiplying into almost an infinity of beings.

Beyond the creatures that populate this section of sublime surrealism, I’m most intrigued by the appearance of wild animals, especially elephants. In one instance an elephant is seen “climbing down through a hole in the clouds,” a feat equated to a kind of end times, “The End of Poetry.” But I remain most intrigued by the magical scene of an elephant in the rain “raising a listless trunk like a kid in the back seat, bored and asking: Are we there yet? Are we there?”

Reading this book of poems won’t leave you asking whether you’re “there” yet. You’ll know you’ve arrived as soon as you enter the portal with its initial enticement: “This Could Be Anyone’s Story.” That’s how straightforwardly real this book is. Real and at the same time, meticulously magical.

*

Heidi Greco’s most recent collection of poems (inanna Publications, 2018) is Practical Anxiety, a condition she freely admits to.

*

The Ormsby Review. More Books. More Reviews. More Often.

Editor/Designer/Writer: Richard Mackie

Publisher: The Ormsby Literary Society

The Ormsby Review is a journal service for serious coverage of B.C. books and authors, hosted by Simon Fraser University. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Robin Fisher, Cole Harris, Wade Davis, Hugh Johnston, Patricia Roy, David Stouck, and Graeme Wynn. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Provincial Government Patron since September 2018: Creative BC

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

Leave a Reply