From alienation to adulation

Condemned in utero as an Enemy Alien in 1942, the scholar and poet Roy Miki (born in 1942) became a hero of the Japanese-Canadian redress movement.

May 25th, 2019

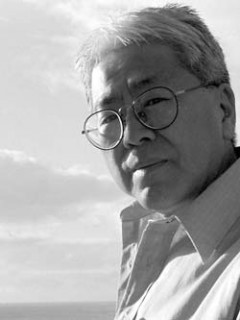

Roy Miki in 2005. His remarkable career as a poet gets its due with a huge volume simply called Flow.

Flow is a wonderful, 640-page tribute by Michael Barnholden and Talonbooks, according to Grahame Ware, who providess an extensive response.

Flow: Poems Collected and New

by Roy Miki, edited by Michael Barnholden

Vancouver: Talonbooks 2018

$49.95 / 9781772012101

Reviewed by Grahame Ware

*

Condemned in utero as an Enemy Alien by the Dominion of Canada in 1942, the scholar and poet Roy Miki (born 1942) emerged as a pioneer of the Japanese-Canadian redress movement of the 1980s.

Reviewer Grahame Ware gives readers fresh insights into the man and his work with his review of Flow, Michael Barnholden’s definitive anthology of Miki’s poetry – Ed.

*

There is a singular impossibility in reviewing a poet/scholar’s life’s work that reminds me of finding one’s way through a labyrinth blindfolded.[1] But the wondrous entanglements of Roy Miki’s life can be unravelled in this brief space without too many shortcuts thanks to anthologist, writer, and Miki’s longtime colleague Michael Barnholden, who does the major work and heavy lifting for Flow: Poems Collected and New, the well produced volume reviewed here. While absorbing this 640-page book and doing some background research of my own, I was stunned by Miki’s energy and dedication to themes not only in his literary output but, more importantly, his life.

There is a singular impossibility in reviewing a poet/scholar’s life’s work that reminds me of finding one’s way through a labyrinth blindfolded.[1] But the wondrous entanglements of Roy Miki’s life can be unravelled in this brief space without too many shortcuts thanks to anthologist, writer, and Miki’s longtime colleague Michael Barnholden, who does the major work and heavy lifting for Flow: Poems Collected and New, the well produced volume reviewed here. While absorbing this 640-page book and doing some background research of my own, I was stunned by Miki’s energy and dedication to themes not only in his literary output but, more importantly, his life.

Art Miki, Roy’s older brother, has provided the Miki family’s early history in B.C. The name Miki came from the boys’ paternal grandmother, Kiyo Miki, the second wife of their grandfather, Yukutaro Shintani. Her family had no males; and Shintani, a naturalized Canadian, returned to Canada with a new bride and a new surname. Their son, Kazuo, born in a logging camp in Tynehead (Surrey), was Art and Roy’s father. In 1935, Kazuo married Shizuko Ooto and the following year Art Miki was born at Tynehead.

Roy Miki’s mother Shizuko (left), pregnant with Roy, arrives in St. Agathe, Manitoba, May 1942. Photo courtesy of Roy Miki

The Miki family remained at Tynehead until 1942, when the federal government ordered the removal of 22,000 Japanese Canadians from the west coast. In May, the family was taken by rail to work on a sugar beet farm in Ste. Agathe, Manitoba. The Mikis were part of a small group of Japanese Canadians who opted to work on farms in the prairies rather than go to the internment camps in the B.C. interior. Ste. Agathe was a different kind of prison but a Siberia nonetheless. They moved from owning and running their lovely Haney berry farm with a creek at the back, to being migrant workers living in a shack on a sugar beet plantation, as Art Miki recalls:

The harsh winter conditions, the terrible non-insulated housing and the short growing season made life difficult. We lived in a four-room house with three families consisting of seven adults and three children. I recall that in November of 1942 my mother who was pregnant had to request special permission from the RCMP to travel to Winnipeg to have my brother, Roy.[2]

Thus, at the time of their removal in 1942 from their west coast home and farm, Roy Miki was but a small, invisible bud on their family tree, his pregnant mother’s silent passenger on their three-day train ride to their version of internment. He spent the first three years of his life leafing out as a toddler in that shack on the farm before the Mikis moved to another Manitoba farm right after the war. Finally, in 1948, his parents bought a house in a tough but affordable (barely) part of Winnipeg when Canada finally revoked the War Measures Act and reinstated citizenship to Japanese Canadians.

With a strong work ethic and belief in the power of education, Art, like Roy, got a B. Ed. from the University of Manitoba. Art spent his career in public school education and, late in his career, became a citizenship judge. [3]

*

Part of Roy Miki’s cotyledon memory remained on the west coast. It would not be until the late sixties that he would go back to his roots, when he let his tendrils wrap around a Masters in English Literature at SFU. Little did he know that he would become fascinated with the west coast Canadian poetry scene and like a healthy plant reach for the light. Poetic photosynthesis would now unfold and flow along nicely.

Miki’s early career in public discourse wasn’t as cerebral as his later poetry, as densely researched as his activist journalism, or as visceral as “Roy Miki and the Downbeats,” the pop rock group he formed as an undergraduate at the University of Manitoba (United College), which gave followers and fans in the canteens in and around Winnipeg a dose of live medleys of Buddy Holly, Fats Domino, and other early rock and R & B acts. It paid for their amps and their cars, which gave them the mobility to be heard. The band eventually proved too time-consuming for the studious lead singer/rhythm guitarist, so Miki’s gig with the Downbeats came unplugged. However, his glimpse of what he could do with words and performance would come in handy in the years to come.

After leaving Winnipeg in 1965, Miki had a brief scholastic sojourn at the University of Toronto where he tried to nail down his post-graduate aspirations. He managed to use his rhythm guitar skills to work up a little Pete Seeger material along with some friends before Beatlemania and psychedelia combined to eclipse the grassroots folk song protest movement. The times really were a changin.’

In Toronto he also decided, with a little advice from his medieval studies professor, that contemporary writing would be his extended engagement. Thus, he took a chance on an MA program at the newly created west coast post-secondary institution, Simon Fraser University. He felt that the U of T’s contemporary literature program wasn’t too exciting and UBC’s Earle Birney encouraged him to give the west coast a try. Unconditional in his praise, Birney believed that Miki could write poetry. To his delight, SFU accepted him for a Masters. The journey to the west coast was a return not only to his family roots but also to where he was conceived. Enrolled in the SFU Masters program, he was “back” on the west coast where he had been condemned in utero as an enemy of the state in 1942.

As Flow, the “definitive edition of Miki’s poetic work” (as touted in the blurb by Talonbooks) shows, the monosemic voice within the dominant postwar political discourse would be questioned by Miki’s literate analog thinking and polysemic narrative. His poetics form a narrative theme that he developed and distilled as a graduate student and professor mainly through his engagement with the work of William Carlos Williams. He then turned his attention to local poets such as bp nicholl, George Bowering, and Roy Kiyooka, in the process preparing some significant award-winning monographs.

As a scholar, he discovered fellow travellers and common themes worthy of further exploration. Around the campfire of historical investigation with his fellow Japanese Canadians Roy Kiyooka, Joy Kogawa, and Tamio Wakayama, he finally saw in the flames a common identity flickering in the eyes of his allies and detected a common darkness and coldness at their backs. He decided to throw his log on this fire to keep it going. And another. And then another.

In the 1970s and 1980s, Miki gained a profile in Canadian culture with his journalistic activism within the Japanese Canadian community. But it wasn’t all campfires and singing. This work took many years to chisel and carve, to bring life and shape to what had been a monolithic column of conservative stone in the cultural landscape of Canada, especially in the 1970s. Many feel that his work in the quarry of culture ultimately was more worthwhile than his poetics mountaineering. The dialectic of “difference” became a source of meaning and a variegated inspiration for his intellect. I would argue that the training and conditioning that Miki received from the often Sisyphean activity of academia prepared him beautifully to recognize and analyze the dynamics that controlled the WASP narrative in English Canadian culture, and provided an insight that added immeasurably to the arc of his poetics.

In the background was the multicultural policy of the Canadian government that emerged with Pierre Trudeau, the main thrust of which was directed to close the English-French Canadian divide. The Nikkei, even after their eventual political “redress” in 1988, still had much healing to do from the wounds of displacement and internment. This would take time — and, of course, more logs on the fire that he and his allies had started.

*

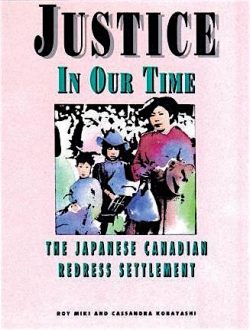

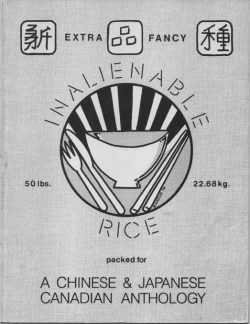

It all began innocently enough as Miki was working on his PhD at UBC. Miki became involved with a number of young, talented, and educated Japanese and Chinese Canadian writers and artists. The Black Power movement and the general rise of political and multicultural consciousness meant that many cultural shackles were being thrown off. For Japanese Canadians, the Powell Street Festival galvanized and distilled themes of renewal and pride. Its organizers included musician/teacher/actor Rick Shiomi,[4] Ken Shikaze, the renowned social activist photographer, Tamio Wakayama,[5] and Takeo Yamashiro.[6] Miki was part of the youthful fervour of the time. Others working on the Powell Street Festival and the Tonari Gumi (the Japanese Community Volunteers Association, founded in 1974) included Kazuko Sonoda, Takeo Miwa, Maya Koizumi, Michiko Sakata, Linda Uyehara Hoffman. Miki’s own activist writing would be published in his poem, “Pre-face to Saving Face” in Inalienable Rice: A Chinese & Japanese Canadian Anthology (1979) – the book that kick-started the whole Japanese Canadian Redress movement. [7] As a result of this publishing project, Miki got involved with the Japanese Canadian Centennial Project with Wakayama. This was also during the period when he was doing his PhD!

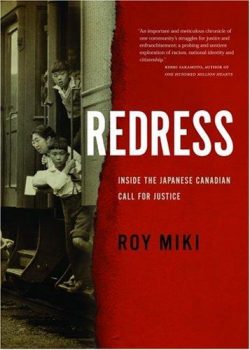

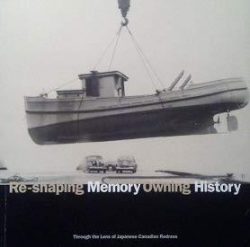

Historian Patricia Roy summarizes this fecund era. “The Vancouver Japanese Canadian Centennial Project resulted in an exhibit of historic photographs and a book, A Dream of Riches: The Japanese Canadians, 1877-1977,” she writes. The warm reception of the exhibit encouraged the organizers to have a grand party to demonstrate how the Nikkei “had survived a century of racial oppression.” They launched the Powell Street Festival, Roy adds, as “a celebration of Japanese traditional culture.” [8] A Dream of Riches marked a new and shameless return to a troubling chapter in Canada’s history. Miki rolled some of this material and history into his seminal book, Redress: Inside the Japanese Canadian Call for Justice (Raincoast Books: 2004). The fire was now really roaring. It had become a bonfire.

In 1977, Miki published in the Powell Street Revue a broadside poem in a centennial memorial to Japanese Canadians entitled, “the japanese canadians 100 years;” and with his poem “Pre-face to Saving Face” in Inalienable Rice (1979), he was finding his thematic stride. While this poem is not included in Flow, it suggests that Miki’s core thesis concerning the trauma of relocation and the need for redress was bred in the bone. Here is a part of the poem:

Relocation — the least of

them waiting like statues. The orchard would

be replaced. There would be no semblances.

Photographs lost in a trunk and later seen

for sale.

And later:

And to be among. There are.

No. Roots.

There. Ships wait.

To be moved. And they.

Too cross. The pacific.

Once. We said.

We say. The world lay.

A mixture. The sun.

The sea. Our children.

Like marigolds. Our boats.

Our nets. We.

Filled our houses. Now.

Thin and brittle. The cold clings.

Now. The inland sea.

This is a powerful description of the wretchedness of dislocation and the manifest traumas that ripped through Japanese Canadian families. Like birds that make nests out of favoured materials as well as what is available, when there is nothing to make nests from, what happens then? Their roots were chopped and their fruit trees felled, but the power of nature was such that they were not dead, just dormant and ready to grow anew.

*

Upon completion of his Masters degree from SFU in 1969, Miki and his wife Slavia Knysh (his high school sweetheart) travelled overseas and ended up spending eighteen months in Japan. It was there that Miki realized that Japan was not for him. Returning to Vancouver, he decided that his best option was to pursue a PhD and he was accepted at UBC. He finished his thesis in 1980, the same year he was hired as an assistant professor by SFU’s English Department, where he had been a sessional instructor for five years. His dissertation, which was later published, concerned the American modernist poet William Carlos Williams, a thinker who taught Miki to embrace modernist writing and crisis.[10]

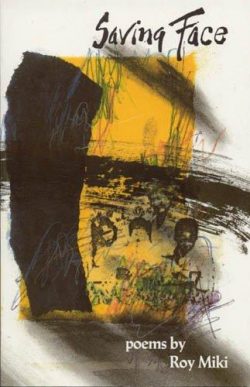

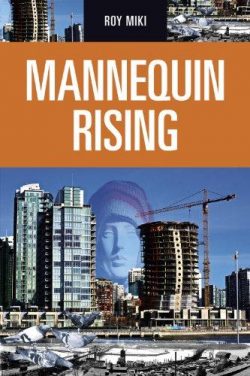

Miki published his first volume of poetry, Saving Face (Turnstone Press, 1991) when he was 49. The writing here is sparse but it reprises some important and abiding themes that he would cultivate for the rest of his life. Like a homesteader with his main field, every year stones and rocks heave up from the freezing and the rains of winter. Miki had to pick up those stones and clear the field before he could plant his crop. Once in a while he came up against a boulder lodged in his earth. No horse, no tractor … just an iron bar and a shovel — mano a rocko.

But in reality Miki has an aversion to working the land. Undoubtedly, it dredged up bad memories. He lived in his head and saw gardening, tilling, and farming as something with the skank of peasantry. As such, it enslaved the mind. Such is the gist of “The Alternative Sources of Energy are Drying Up:”

useless the rooster that crows

the finite flowers

& the row of dead dreams

waiting to be covered

like birds of a feather

i’m useless

with hammer & saw

& would rather hear

than see the ink dry

bulbs & briars

& forgetmenots do not

a full head make (Saving Face, p. 36).

But the rocks and boulders in his literary and psychic field had to be dealt with. The pile of rocks grew steadily at the edge of the productive field. Suddenly, almost at the end of Saving Face, is a poem called “A Redress Note:”

never thought it possible in my generation to

witness, not just witness but to be involved in the phenomenal

shifting going on within this internal space of our lives as jcs (p. 58).

The jcs referenced are the Japanese Canadians. The internment of 1942 was the big rock lodged in Miki’s psychic field. In Saving Face he showed that he might just be able to wrest it out, but he didn’t yet have quite enough leverage with his bar. Most importantly for Miki, he found that he was not alone in “clearing this field,” as he told Kirsten Emiko McAllister in 2012:

For Japanese Canadians, and for me in particular as a child of the mass uprooting, the historic moment of internment has functioned as a constituting temporal marker. I have written about this history as both a burden and gift — a burden because it was such a time of major upheaval for my family, but a gift because it has given me a subjectivity that motivated me to become a writer and teacher.

The problem — and this is always a danger for a poet — is that subsequent memory formations are usually restricted by what become articulated as foundational historic events, like the mass uprooting, and therefore, to an extent, are over-determined by these constituting markers. Without in any way taking away from the value of writing that makes visible these markers, to be conscious of the present we also need to be open to new formations that transform our relation to our memories of the past while maintaining a critical engagement with what is happening around us.[11]

Miki’s poetics, based on the mass uprooting of 1942, are connected by the over-arching narrative of trauma theory. A unified narrative of modernism and trauma is at play here — as in the most notable poetics of the twentieth century

*

The writerly and technical introduction to Flow: Poems Collected and New is provided by Louis Cabri, who also introduced Fred Wah’s anthology, The False Laws of Narrative (Wilfred Laurier University Press, 2009). Cabri subsidizes his poetry-making habit by teaching at the University of Windsor and apparently he’s worth his salt. Windsor — of course! But Cabri’s salt is iodized with too many abstruse crystals. You’ll need more than a salt grinder to render his salt for inverse decoding.

While much of Flow considers Miki’s poetry, I found it productive to pursue his prose and editorial work. His first turn in the editor’s chair was for the 1978 broadside, Six BC Poets, composed of six 13” x 9 7/8” broadsides, housed in a tri-fold, printed paper folder. It was issued in an edition of 350 on the occasion of the B.C. Heritage Poetry festival held — where else? — in the Student Union Pub at Simon Fraser University in May 1978. It combined a work each by George Bowering, Daphne Marlatt, Lionel Kearns, Robin Blaser, Brian Fawcett, and Fred Wah.

Miki has shown real strength as a cicerone for others, spelling it all out in non-fiction anthologies. Miki’s anthologies include Pacific Windows, a collaboration started before Roy Kiyooka’s passing and completed in 1997, the year after he died.[12]

His critical monographs on west coast poets bp nicholl, George Bowering, and most importantly Kiyooka bear out American poet Ron Silliman’s comments on Miki’s importance as an anthologist. “Roy Kiyooka isn’t nearly as famous as, say, I think he should be,” ventures Silliman. “And, there are more than a few other next gen New Americans who have disappeared from view altogether — Seymour Faust, Harold Dull, d alexander to name three — who would likewise benefit greatly if a Roy Miki would come and gather together a collected works for somebody to publish.”[13]

*

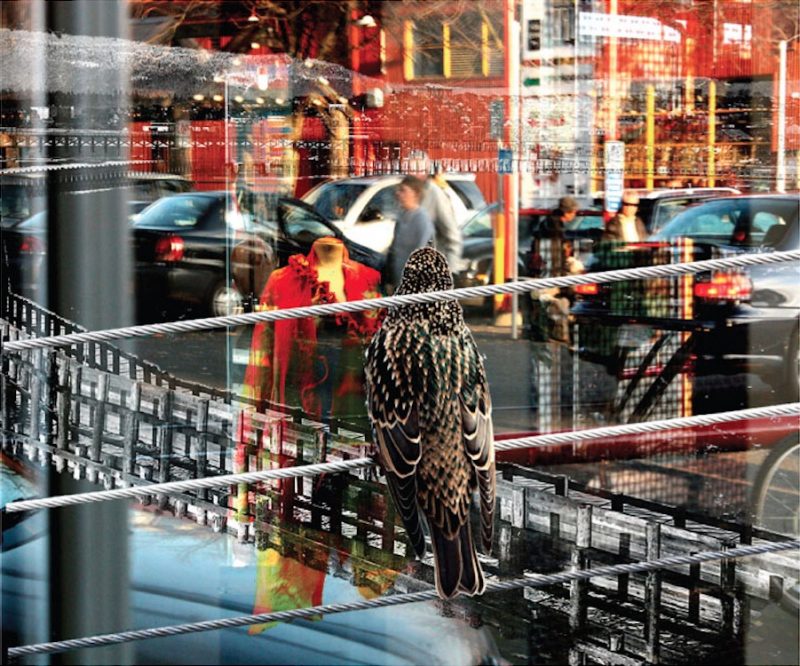

In an attempt to expand the field of poetry, Miki began to use photos in his work. This evolved into a photo-collage technique using Photoshop. In this approach he followed Kiyooka’s interdisciplinary work. Pictures used as foils became a visual, contrapuntal device to make the language more grounded and impart to it greater scope. Like all writers, Miki has his heroes, one of whom was Kiyooka. The two men shared many similarities but Kiyooka was much more visceral. Miki interviewed him many times: the first time I can detect was in Inalienable Rice (1979), followed by an interesting publication by the Artspeak Gallery in 1991 entitled Roy Kiyooka. Cate Rimmer of Artspeak and Nancy Shaw of Or Gallery curated the accompanying show and the publication. Some guy named Stan Douglas did the pics for this tidy monograph.

Photo montages feature in Miki’s subsequent poetry, as he explained to McAllister:

While Harry [Roy Kiyooka’s artist brother] and I walked through Victoria Park, I found myself noting certain similarities with my own very poor childhood neighbourhood in central Winnipeg, the Logan area, where I grew up in the postwar years. Even the structure of the houses resembled those in my own memory.

When I began to consider the possibility of writing a series of poems alongside the photos, I started by imagining that these images, which only obliquely represented the geography of Kiyooka’s childhood, were reflections of my own childhood neighbourhood, and, almost impossibly, that my imagination of Kiyooka’s childhood would become a screen on which I could explore elements of resistance, escape, and empowerment in my own childhood. In this way, the poems could function as a creative and critical remembering that did not merely service the interests of the autobiographic “I.”[14]

The grandson of a samurai, Kiyooka’s own “selfie” black and white nude photos — it was a hot day on Keefer Street — graced the Inalienable Rice anthology where Miki did his first interview. Kiyooka was like a raven. I feel that Miki learned so much from him. He was viscerally talented in ways that Miki never could be. Miki truly revered his “out there-edness.” His admiration for Kiyooka’s being and art, I would argue, expanded his poetical frame of reference and raised his artistic consciousness. The first “Roy-interviews-Roy” event came twelve years before Miki issued his first volume of poetry.

Years after Kiyooka’s passing, thinkers, artists, and scholars would make reference to the notion of “ancestral memory” as a component of his identity. Like the seed that locks in day length (periodicity) and hygroscopy (temperature/moisture ratio), so too a human being never loses its desire for its own garden, its sweet spot on the earth, recognizing the moisture and the light levels and length of daylight so that germination is possible. See link here.

*

Editor and anthologist Michael Barnholden and Roy Miki became connected intellectually through — guess who? — Roy Kiyooka, as Barnholden explains:

A close reading of Pacific Windows: Collected Poems of Roy Kiyooka (Talonbooks 1997), reveals much about his poetry and poetics. I had the pleasure of doing the production work on this volume. Many of Kiyooka’s publications can only be viewed in this format as they were self published in limited editions, for all intents and purposes artists’ books, never commercially available, given to a few carefully chosen friends and colleagues around the world. I also got to work closely with editor Roy Miki, and often had the good fortune to be able to test my reading of Kiyooka with and against his knowledge of Kiyooka and his work. Editor Miki has assembled a comprehensive bibliography of Kiyooka’s poetry published in book form. What becomes clear is that part of his cultural work was as a publisher, ten of his twenty books of poetry published during his life were self published.[15]

In poetry circles, Barnholden is best known for his active involvement with the Kootenay School of Writing, an internationally recognized experimental writing group. He published many of the early KSW chapbooks under the imprint of Tsunami Editions and, with his colleague Andrew Klobucar, co-edited Writing Class: The Kootenay School of Writing Anthology (New Star, 1999).

Now based in Vancouver, Barnholden continues to write, teach, and encourage innovative writing. Since 2003 he has done so primarily through his book review periodical, The Rain Review of Books. Recently, he’s been busy as the managing editor of West Coast Line (SFU) and publisher of its offspring, LINEBooks. Not surprisingly, he teaches at SFU. And now that Barnholden has turned to Miki, the anthologist has been anthologized.

Miki’s poetry seems indifferent to whether or not it engages you. Its casual formality makes many take it for granted. You do so at your peril. You are supposed to work hard to de-code the enjambments, the double meanings, and the Williams-esque word collages and rhythms. It may be stratospheric to some. Meanwhile, back on terra firma, Miki is also the quiet activist parsing the racialized language that tethers our minds to the slippery slope of the dominant ideology that uses language against us.

For all of his work in the redress campaign (and, perhaps, anthologizing west coast poets), Miki received the Order of Canada in 2006. One is tempted to compare him and his activities as a scholar and activist with the granddaddy of them all, George Woodcock, but Woodcock was the gentle anarchist who refused the Order of Canada. So too did Glenn Gould and Alice Munro, among others. Roy Kiyooka accepted his OC but flaunted the black tux rule by finding an emerald green one apparently spirited from a St. Patrick’s Day celebrant.

In an off the rack world, everyone is looking for a custom cut. Miki has finally been able to dress the way he wants and cloak himself in a role he’s tailored for his own custom look. But he doesn’t do it from vanity. He does it because he can. He desired not only a re-dress for himself but for his family and all Japanese Canadians. And, paradoxically, though he thinks that he doesn’t have a green thumb, the DNA of his deep self enabled him to cultivate beautiful things. He dreamed of his own spot near the creek in Haney where he never got to dip for crayfish. The loss of that and so much else meant a long, painful meditation.

Yes, Roy Miki planted a garden like few Canadians and curated a terrain that few saw as fertile. He understood what was needed for a garden to grow in a zone that had little humus and a mineralized strata. He kept at his rock garden and showed us what it could be. The unusual beauty of this metaphorical garden was made all the more astonishing and startling because of the contrast with the mountain rock. Best of all, he shared that garden and gave us a tour so we could see it blooming for ourselves. It is one that we’ll never forget.

And, like Bill Reid, Miki has gone through a process within Canadian culture from alienation to adulation. Miki has fought his battles and spoken his mind. Flow is a wonderful and fitting tribute to him by Michael Barnholden and Talonbooks.

*

Grahame Ware is a writer and reviewer living on Gabriola Island.

*

The Ormsby Review. More Books. More Reviews. More Often.

Editor/Designer/Writer: Richard Mackie

Publisher: The Ormsby Literary Society

The Ormsby Review is a journal service for serious coverage of B.C. books and authors, hosted by Simon Fraser University. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Robin Fisher, Cole Harris, Wade Davis, Hugh Johnston, Patricia Roy, David Stouck, and Graeme Wynn. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Provincial Government Patron since September 2018: Creative BC

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

Endnotes:

[1] Reviewer’s note: My gratitude to Roy Miki, who has been kind enough to provide me with some biographical details and correct a few others. Thanks also to Fumiko Kiyooka for her input about her father Roy and for access to her fine documentary about him, Reed. Kudos to Sonja Arntzen for providing me with the books, Inalienable Rice and Roy Kiyooka, which were invaluable resources; and, finally, to dramatist and performer Rick Shiomi for identifying pictures in Tamio Wakayama’s book, Kikyo: Coming Home To Powell Street. I have not received any reimbursements for this review other than the usual review copy. I also make this statement for clarification: my reviews are grounded in history and literary journalism and, as such, the criteria and style are not strictly academic but geared to the general audience of The Ormsby Review. Any and all mistakes or errors are mine alone. As always, much gratitude to Richard Mackie at The Ormsby Review. — Grahame Ware, May 11 2019.

[2] Interview with Art Miki in John Endo Greenaway, “Art Miki: a life in service,” August 24, 2012, in The Bulletin: A Journal of Japanese Canadian Community History & Culture http://jccabulletin-geppo.ca/art-miki-a-life-in-service/

[3] Interview with Art Miki in John Endo Greenaway, August 24, 2012.

[4] Now a celebrated playwright and director based in Minnesota, Rick Shiomi was then an SFU educated teacher and musician and a creative cultural force. He helped found Katari Taiko after meeting Kenny Endo in San Francisco; they performed first at the Powell Street Festival, for which he was manager between 1977 and 1982. His Yellow Fever premiered in 1982 at the Asian American Theatre Co. in San Francisco and later met rave reviews in New York. See https://www.mcknight.org/wp-content/uploads/Rick_Shiomi_2015DAA_FINAL-2.pdf

[5] For the amazing life of Tamio Wakayama see https://snccdigital.org/people/tamio-wakayama/

[6] Born in Hiroshima in July 1943, Takeo Yamashiro is a registered survivor of the atomic bombing of August 6, 1945. He was two years old at the time. He has been one of the most influential shakuhachi masters in North America over the past four decades; a pioneer in the field of cross-cultural, jazz, world and creative music; the first professional musician specializing in Japanese traditional music among the post-war immigrants to Canada; and well known for his commitment and devotion to community work as co-founder of Tonari Gumi and project sponsor of the first Annual Powell Street Festival.

[7] Inalienable Rice: A Chinese & Japanese Canadian Anthology (Vancouver: Powell Street Revue and the Chinese Canadian Writers Workshop, 1979), p. 54.

[8] Patricia E. Roy, “The Re-creation of Vancouver’s Japanese Community, 1945-2008,” Journal of the Canadian Historical Association, 19:2 (2008), pp. 127–154).

[9] Roy Miki in Inalienable Rice: A Chinese & Japanese Canadian Anthology, p. 74.

[10] Roy Miki, “A Preface to William Carlos Williams: The Prepoetics of Kora in Hell: Improvisations,” PhD dissertation, UBC, 1980.

[11] Kirsten Emiko McAllister, “Interview: Between the Photograph and the Poem: A Dialogue on Poetic Practice with Roy Miki,” Canadian Journal of Communication 37:1 (2012), pp. 217-236; p. 232.

[12] Roy Miki, ed., Pacific Windows: Collected Poems of Roy K. Kiyooka (Talonbooks, 1997).

[13] https://ronsilliman.blogspot.com/2005_03_06_archive.html

[14] McAllister, “Between the Photograph and the Poem,” p. 232.

[15] Michael Barnholden, “Under the Logos of the Blue Mule: Self Publishing the Serial Poems of Roy Kiyooka,” dANDelion (Spring 2003): http://www.kswnet.org/texts/Barnholden_on_Kiyookas_4th-Avenue-Poems.pdf

L-R: Julie Flett, Roy Miki, Slavia Miki at BC Book Prizes 2015, winners for Dolphin SOS (Tradewind Books, 2014). Photo courtesy of the Vancouver Courier

Leave a Reply