#405 Crows and crime scenes

October 22nd, 2018

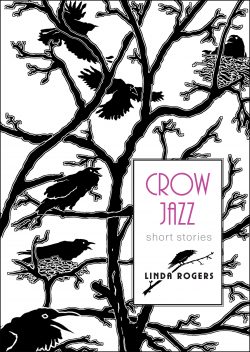

Crow Jazz

by Linda Rogers, illustrated by Rick Van Krugel

Salt Spring Island: Mother Tongue Publishing, 2018

$23.95 / 9781896949659

Reviewed by Paul Headrick

*

Editor’s note: Victoria poet Linda Rogers turns to fiction in Crow Jazz, a collection of 20+ short stories from Mother Tongue Publishing, many of them set in Vancouver’s West Point Grey, where Rogers grew up. Her father, Ormonde Hall — known as Ormie or O.J. to his friends — was a specialist in publication law. “He was a lawyer, the University solicitor and founding member of the Ubyssey,” Rogers noted in an email to the Ormsby Review. Historians Margaret Ormsby and Margaret Prang were also familiar names in this childhood on the edges of the UBC community.

West Point Grey, Chancellor Boulevard, the University Golf Club, and the forested UBC endowment lands all provide settings and sometimes a dark backdrop to Rogers’ stories of her childhood. “The question these stories raise is often not so much what’s going to happen, but what’s going on,” notes Ormsby reviewer Paul Headrick. — Ed.

*

Linda Rogers’s Crow Jazz is a challenging, perplexing, and glorious collection of stories, perhaps just what we would expect from a poet whose startling juxtapositions of real and surreal produce such remarkable effects. In one story, the writer-narrator’s husband describes her work as “‘ordered chaos, a one-of-a-kind gestalt’” (pp. 46-47). That’s a fine description of what readers are in for here.

Linda Rogers’s Crow Jazz is a challenging, perplexing, and glorious collection of stories, perhaps just what we would expect from a poet whose startling juxtapositions of real and surreal produce such remarkable effects. In one story, the writer-narrator’s husband describes her work as “‘ordered chaos, a one-of-a-kind gestalt’” (pp. 46-47). That’s a fine description of what readers are in for here.

In “The Writing Life,” an autobiographical piece included in Linda Rogers: Essays on Her Works (Guernica Editions), Rogers describes her visits to a facility for severely disabled children: “Most of the patients are the victims of asphyxiation. It is hard to believe we let it happen. They are a metaphor for all the children who are not getting enough air” (pp. 166). If there’s a single order-bringing element to the artful chaos of Crow Jazz, it’s Rogers’s ongoing concern for children and the way we have deeply failed so many of them. In these stories suffocating children abound.

The main character of the powerful opening story, “The Ranger,” recalls a time in her youth when she routinely escaped the adult world to play in the forest that borders Vancouver’s University Golf Club. There, she and other children encounter the odd man named in the title, who scavenges the same territory, collecting golf balls. In the rumours the children recount to each other The Ranger becomes a folk-tale figure — the threat in the heart of the forest, cooking children and golf balls together to make food to feed his dogs.

The Ranger might present a genuine, physical danger, but it’s clear that he is a projection of other sources of evil in the world the narrator recalls. These include the men who cruise Chancellor Boulevard offering her rides, and the dentist, perhaps a pedophile, who crams her mouth with unnecessary fillings in return for legal services from her lawyer-father. The worst, however, the truly damaging force, is subtle and pervasive. The narrator identifies it when explaining why she continued to risk those forest adventures: “There were no narcissistic parents battling for supremacy in my woods” (p. 4). It’s this parental narcissism, painfully revealed by comments the adults make, by their self-serving excuses for their neglect, or worse, that sucks the oxygen out of the air that Rogers’s children must breathe.

The Ranger might present a genuine, physical danger, but it’s clear that he is a projection of other sources of evil in the world the narrator recalls. These include the men who cruise Chancellor Boulevard offering her rides, and the dentist, perhaps a pedophile, who crams her mouth with unnecessary fillings in return for legal services from her lawyer-father. The worst, however, the truly damaging force, is subtle and pervasive. The narrator identifies it when explaining why she continued to risk those forest adventures: “There were no narcissistic parents battling for supremacy in my woods” (p. 4). It’s this parental narcissism, painfully revealed by comments the adults make, by their self-serving excuses for their neglect, or worse, that sucks the oxygen out of the air that Rogers’s children must breathe.

Chaos, however skillfully managed, presents difficulties. The question these stories raise is often not so much what’s going to happen, but what’s going on. Narrators launch into their tales while offering few clues as to who is speaking, or anything that locates the characters in time or place. Seldom are the characters named, initially at least; they’re referred to only by pronouns. One of the writer-characters asserts, “I am not into plot exegesis” (p. 136). I could sympathize with a reader connecting the protagonist to Rogers herself and thinking “no kidding.”

The absence of helpful information might seem at first simply a matter of style, but another explanation gains force as the connections between the stories build: the narrators’ persistence in withholding the background details of more conventional story-telling expresses the persistence of trauma in their lives. In one way or another they have been dislocated, and all they have left to establish their identities is their words.

The absence of helpful information might seem at first simply a matter of style, but another explanation gains force as the connections between the stories build: the narrators’ persistence in withholding the background details of more conventional story-telling expresses the persistence of trauma in their lives. In one way or another they have been dislocated, and all they have left to establish their identities is their words.

In many of these stories the characters have endured sexual abuse, and through their words, their descriptive powers, they gain a kind of heroism. In “Bedtime Stories,” the narrator briefly refers to being exploited as a child, and then she tells us of her first orgasm, experienced after a forest picnic while her lover plays his violin for her: “after sup and sip, a murder of crows tangled wings, a frisson, in the yellow-taped crime zone between my legs” (p. 161). The metaphor is wrenching in the damage it conveys, and yet the passage is marvellously uplifting, because that “frisson” is positive, obviously, but also because of the character the language implies. She is terribly damaged, but she is an artist.

Though much of the material is dark, the stories are often very funny, the humour sly. Some readers will smile at certain names and the era they evoke: Moon, Sun, Windsong, Forest. A reference to “the Hate Pumpkin” or to the time when “Agent Orange declared war on Mexico” might be confusing at first, but it’s a jokey relief to realize that every narrator refuses to dignify the leader of our neighbour to the south by referring to him by name. With Rogers, however, jokes are always in some way serious. The stories can be at their most biting when dramatizing the almost sadistic irresponsibility of self-identified former hippies, and an accusation emerges out of the references to the unnamed one — we are witnessing the brutal culmination of our own narcissism.

Though much of the material is dark, the stories are often very funny, the humour sly. Some readers will smile at certain names and the era they evoke: Moon, Sun, Windsong, Forest. A reference to “the Hate Pumpkin” or to the time when “Agent Orange declared war on Mexico” might be confusing at first, but it’s a jokey relief to realize that every narrator refuses to dignify the leader of our neighbour to the south by referring to him by name. With Rogers, however, jokes are always in some way serious. The stories can be at their most biting when dramatizing the almost sadistic irresponsibility of self-identified former hippies, and an accusation emerges out of the references to the unnamed one — we are witnessing the brutal culmination of our own narcissism.

Details linking the stories accumulate in a manner that’s both delightful and intriguing. In two different stories a woman’s husband is an admirer of the same jazz artist. An Inuit sculpture of two polar bears copulating, disfigured so as to seem to be a single bear with six legs, travels from one story to another. More than one child has a “wettums doll.” A character buries something tragic and secret at the base of a tree, and so does another, and another. These links expand to include other works by Rogers. The narrator of Say My Name, or at least a character who shares the same name, reappears in Crow Jazz, as do characters and incidents from The Empress Letters, both of which novels also describe children whose worlds betray them.

As I read the last of the tales in Crow Jazz, the detailed links contributed to my growing sense of an underlying continuity. I was reading a single, complicated story. It’s a story that reveals our world to be horribly troubled by sexual violence, misogyny, selfishness, and by a refusal to respect children and accept our responsibilities to them. Yet it’s a beautiful story, a lyrical celebration of language and identity, and a refusal to be defeated.

As I read the last of the tales in Crow Jazz, the detailed links contributed to my growing sense of an underlying continuity. I was reading a single, complicated story. It’s a story that reveals our world to be horribly troubled by sexual violence, misogyny, selfishness, and by a refusal to respect children and accept our responsibilities to them. Yet it’s a beautiful story, a lyrical celebration of language and identity, and a refusal to be defeated.

In recent years there has been a number of tremendously accomplished short story collections published by B.C. writers, among them Caroline Adderson, Anne Fleming, Cynthia Flood, Shaena Lambert, and Kathy Page. Rogers can be added to that list. It’s an extraordinary flourishing of the genre, and I don’t know if it’s been noticed or remarked on. At the very least there’s a PhD topic waiting for someone.

*

Paul Headrick is the author of a novel, That Tune Clutches My Heart (Gaspereau Press, 2008; finalist for the BC Book Prize for Fiction), and a collection of short stories, The Doctrine of Affections (Freehand Books, 2010; finalist for the Alberta Book Award for Trade Fiction). He has also published a textbook, A Method for Writing Essays about Literature (Thomas Nelson, 2009; 3rd edition 2016). Paul has an M.A. in Creative Writing and a Ph.D. in English Literature. He taught creative writing for many years at Langara College and gave workshops at writers’ festivals from Denman Island to San Miguel de Allende, Mexico. Recently he was a mentor for the graduate fiction workshop in The Writer’s Studio at SFU.

*

The Ormsby Review. More Books. More Reviews. More Often.

Reviews Editor: Richard Mackie

Reviews Publisher/Designer: Alan Twigg

The Ormsby Review is a journal service for serious coverage of B.C. books and authors, hosted by Simon Fraser University. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Robin Fisher, Cole Harris, Wade Davis, Hugh Johnston, Patricia Roy, David Stouck, and Graeme Wynn. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. As of September, 2018, Provincial Government Patron: Creative BC

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

Leave a Reply