#211 A mysterious, difficult architect

November 26th, 2017

ESSAY: The Mysterious and Difficult Hermann Otto Tiedemann

By Robert Ratcliffe Taylor

*

In this Ormsby exclusive, Robert (Rob) Ratcliffe Taylor offers a 5,000-word biography of Hermann Otto Tiedemann (1821-1891), the German-born surveyor, engineer, architect, and artist. He was one of thousands who were attracted to Victoria in 1858. Unlike the vast majority, he made a name for himself and left an enduring legacy.

In a previous short biography by architectural historian Rhodri Windsor-Liscombe, Tiedemann was cited as “the recently founded colony’s first professional architect.”[1]

Whether Tiedemann was adequately educated and trained to merit this distinction can be called into question. Taylor notes that rival architects had a field day with Tiedemann’s eclectic structures and styles, calling them “pagodas,” “Oriental,” “foreign,” “bird cages,” “farmhouses,” and even “consumptive.”

One of Tiedemann’s churches was dismissed as displaying “the rudest travesty of Gothic.” A church tower he designed was denigrated “the most atrocious architectural abortion.”

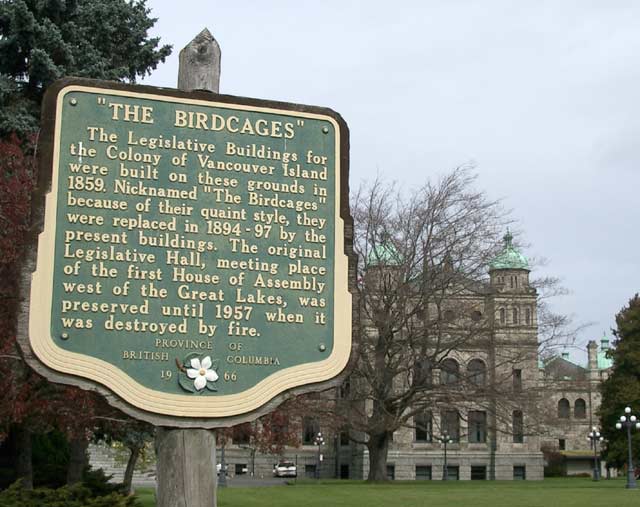

But despite some professional jealousy and rivalry, Tiedemann made a successful, productive, and lengthy career in British Columbia. He is best remembered for the “Birdcages” — the first legislative buildings on Victoria Harbour — but he designed much else, including Fisgard Lighthouse, the Provincial Law Courts, and the main Anglican and Presbyterian churches in Victoria. — Ed

*

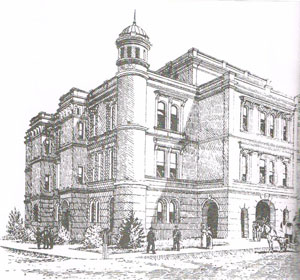

The old lawcourts in Bastion Square, originally designed by Tiedemann. Photo by Victoria Online Sightseeing Tours.

On Bastion Square, in the heart of Victoria’s Old Town, stands an imposing if graceless building, the former Provincial Law Courts. Three storeys high and sporting turrets, corner towers and an imposing arched entrance, it was completed in 1889 and served as the Maritime Museum of British Columbia from 1964 to 2014.

Designed by Hermann Otto Tiedemann, a Prussian immigrant, it is the only one of his several larger contracts to have survived into the twenty-first century. Recognizing its historical significance, the local authorities have entered it on Victoria’s Community Heritage Register. As well as the Law Courts, Tiedemann designed the original St. Andrew’s Presbyterian Church, the Anglican Christ Church Cathedral, and B.C.’s first legislative buildings, the “Birdcages,” all of which have long since been razed.

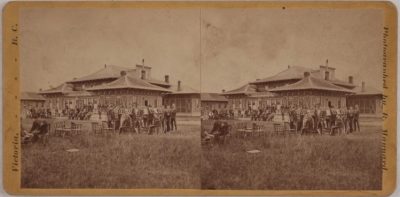

Despite general public disparagement and arguably faulty construction, the “Birdcages” were the largest and most important of his commissions. They served as the hub of west coast political life and as a venue for local social events for nearly forty years until they were torn down in 1897 — all except one, the Hall of Assembly, which was converted into a Museum of Minerals, a function which it performed until 1957 when it burned.

As for Tiedemann himself, his life was that of an enterprising surveyor, a prolific architect and a skilled artist, one of the most interesting of Victoria’s nineteenth century residents. He was also a man who was a difficult colleague with a mysterious past.

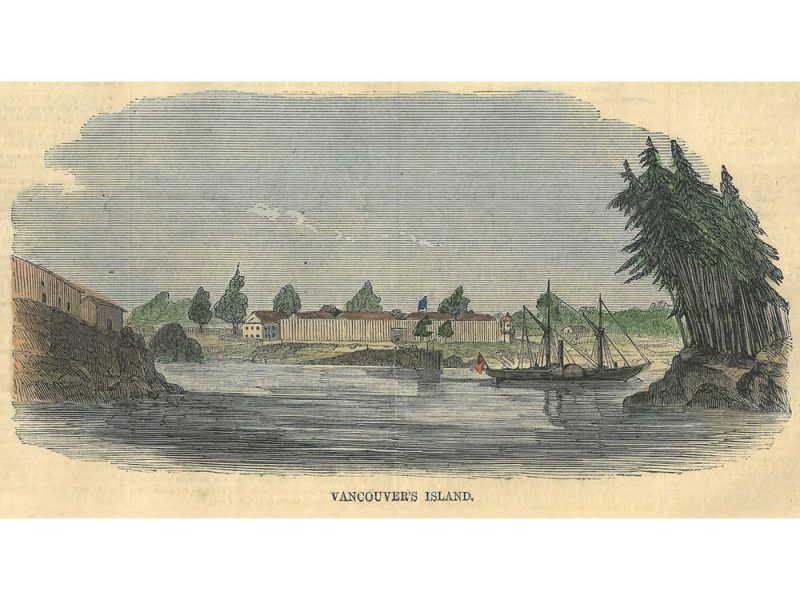

July 17, 1858 illustration from from Harper’s Weekly magazine showing Vancouver’s Island, probably Fort Victoria. It was included in an article about the discovery of gold “on the shores of Frazer’s and Thompson’s rivers” in what would become British Columbia. The gold rush would be one of the big factors in the establishment of the colony of British Columbia on Aug. 2, 1858. For a John Mackie story. [PNG Merlin Archive]

But why did he leave Europe, arriving in the “wild west” of North America at a relatively mature age? Several hypotheses come to mind. Conceivably his prickly character had alienated family and friends, and therefore limited his prospects, motivating him to seek new connections elsewhere. Perhaps he had wanted to avoid compulsory military service, as was the law in many German states. Or was he one of the many young men who had been compelled to flee Germany as a result of the Revolutions of 1848, either because banished by the authorities or of their own free will?

Tiedemann was interested in mining (which suggests that he had such a previous career in Germany or elsewhere). On 12 March 1864, he petitioned the Colonial Secretary in Victoria for permission to prospect for a “vein of coal” in the Shawnigan District. He wanted to form a company and stated that he was “assured of the aid of San Francisco and other capitalists.”[3] Perhaps, as a resident there, he had made contacts in California or had relatives living in the state. (The San Francisco City Directory for 1855 and 1858 lists a Hermann “Tietemann”, “porter.”) The records do not show whether he received permission for the Shawnigan project or formed the company he mentioned. On the other hand, in 1869, he and a partner were granted a reserve of mineral land in Baynes Sound (between Denman Island and Vancouver Island) to an extent of 2000 acres for one year.

As a young man in Prussia, had he become afflicted with “gold fever”? As so many did, he may have spent time prospecting in California, before coming north to Vancouver Island in 1858, the year of the Fraser River Gold Rush. If he had contracted the lust for gold previously, he experienced a recurrence on 18 August 1873, when he asked the colony’s Chief Commissioner of Lands and Works for permission to “prospect the rocks extending out to the Sea from the foot of Menzies Street along the shore to the boundary of Beacon Hill [in Victoria]… for gold silver, etc.”[4]

Even if he never lived in California with compatriots, Victoria would not have been linguistically foreign to Tiedemann because a German-speaking element had settled in the colony. H.F. Heisterman, for example, had became a successful local real estate agent and was president of the Germania Singverein. German-speaking merchants here had business connections with San Francisco, which may have been how Tiedemann first learned about Victoria.

Whatever the truth in these surmises, indubitably Tiedemann was a daring traveller, even in an age when thousands of people journeyed in dangerous conditions over great distances over sea and land. Not only did he leave his native land for the remote west of North America but he also canoed up the Strait of Georgia into Bute Inlet and followed the Homathko River on a surveying project (see below). Later in his life, he travelled across the continent to New York City, although the purpose of that trip is not clear.[5]

At all events, soon after his arrival at Fort Victoria, he was hired by the colonial Land Office as Assistant and Principal Draftsman to Joseph Despard Pemberton (1821-1893, Surveyor-General of Vancouver Island.[6] He may have carried with him a diploma or some other statement of work experience but, in those colonial days, the qualifications of men who claimed to be professionals were not often or easily checked. On 18 January 1859, Colonial Secretary William Young (1827-1885) received a letter from Pemberton, presumably recommending him as designer for new Government Buildings planned for the south shore of James Bay near Fort Victoria.

The Prussian was an “accurate surveyor,” Pemberton wrote, and a “finished [sic] artist.”[7] The latter talent is evident in his panorama of Victoria, circa 1860, and in his being commissioned to make an “illuminated” address of welcome for the visiting Duke of Connaught in 1890. (This would have had a text with initial capital letters and some of the text embellished with gold.)

A question, however, remains: why, so early in his tenure at the Land Office, was the relatively unknown and non-British Tiedemann, with no apparent experience as an architect, chosen to fulfill such an important commission? Perhaps he had in fact presented letters of recommendation from Europe or California or, in the several months of his employment in the colony, he had impressed Pemberton with his talents.

The peculiar circumstances of the unsophisticated colony suggest another answer. At this time much government business was still directed personally by Governor James Douglas, who seems to have readily accepted Pemberton’s recommendation of the German and authorized his appointment. Pemberton, a former Hudson’s Bay Company man, was well known and presumably trusted by Douglas, who had had a long association with the HBC.

Furthermore, the official protocols for granting commissions for the design of public buildings were still non-existent in the colony. Unlike in 1892, when the more grandiose replacement for the Birdcages was envisaged, no competition was held.

As well, the usage of professional titles was still fluid in this frontier settlement. Engineers, surveyors, and contractors all could practice as architects and identify themselves as such.[8] Although he is often considered as Victoria’s first professional architect, Tiedemann was not the only man living and plying related crafts in the vicinity at the time. In this bustling gold boomtown, several residents called themselves engineers, surveyors, builders, contractors and carpenters — and three referred to themselves as “architects.” The latter were Rudolphe D’Heureuse, on Yates Street; Edward Mallandaine, at Broad and Yates; and John Wright, also on Yates Street.

Typically, John Teague, who as an architect later designed several of Victoria’s most prominent structures, was entered in the 1860 Directory only as “cabinetmaker and undertaker, Trounce Street.” Tiedemann’s entry in that Directory lists him briefly with the phrase “Land Office,” with no profession and no address.

Such men may have preferred to work as architects but in the changing, unstable economy of the west coast colony, they had to be flexible in defining their talents. Like Tiedemann, many worked as engineers, surveyors, and contractors. In fact, throughout North America, only over time did a clear differentiation between architects (engaged in creative design) and surveyors (concerned with precise measurement on the ground) become fixed.

Nevertheless, the choice of a non-British subject was deemed problematic in one quarter. Tiedemann’s Continental heritage was stressed by the journalist and democrat Amor De Cosmos (1825-1897) in his denunciation of the Birdcages: “such an extraordinary specimen of architecture,” he wrote, “could never have emanated from the brain of the wildest Englishman.” Moreover, this “foreign” gentleman could have no deep interest in or commitment to the colony, he said, but probably wanted only to make some money and return home.[9] (In fact, Tiedemann would become a British subject in January 1863.) Although Tiedemann’s fellow architects, Mallandaine, Teague, and Wright, were British-born, his German roots do not seem to have been held against him by Pemberton. Despite their sometimes bitter rivalry, moreover, I have found no evidence that his fellow architects denigrated his ethnic roots.

The 1881 census, however, lists both him and his three surviving Victoria-born sons as “Prussian.” His wife Mary is described as “Scotch” and, with their sons, as “Presbyterian.” On the other hand, he is labeled “Lutheran.” Why did Tiedemann impress upon the census-taker the German heritage of his boys? Here lies another enigma about this possibly conflicted man.

Although he was relatively fluent in the English language, a clumsily expressed letter of 7 January 1860 from Tiedemann to Acting Surveyor Benjamin Pearse (1832-1902) suggests that his command of the tongue was not perfect.[10] (The letter is a copy, so the fault may not be the author’s.) In his Report to Alfred Waddington (1801-1872) on his 1862 Bute Inlet surveying expedition and in the associated Journal, however, some spelling errors are found but these mistakes could have easily been made by a native English speaker.

Nevertheless, the fact that his first language was German is evident in the occasional awkwardness of style and several instances where he uses a German word instead of an English one.[11] His grammar and vocabulary, however, are fairly good. Conceivably he had picked up some knowledge of the language in the years between completing his training in Germany and his arrival in Victoria. Whether he developed his English in Britain or in California, of course, is part of the mystery of his early life.

Although the Victoria Directory editor may not have granted him the title of “Architect” or he may have been too modest in 1860 to claim to be a member of that profession, he had one advantage over the aforementioned gentlemen. He was Assistant and Principal Draftsman to Surveyor-General Pemberton, who seems to have identified his potential as an architect. His daily proximity to the man who would choose the designer of the new structures, therefore, may have given him an edge over other likely contenders. As well, Pemberton may have wanted an “in-house” man to do the job, someone he could oversee regularly.

Tiedemann had yet another possible advantage over British-born and-educated men. At this time, German schools and universities were considered the best in the Western world, a reputation that might have worked in his favour. As noted above, his training could have been at the Berlin Building Academy where it would have been thoroughgoing. Possibly he had some experience in work related to engineering, surveying, or even architecture in Prussia. His later employer, the Englishman Alfred Waddington, had attended the University of Göttingen, a fact that may have favourably disposed him to the Prussian.[12]

Tiedemann’s German background may also have played a role in his layout of the precinct comprising the Birdcages (the new Government Buildings). Here, he situated the House of Assembly behind the larger, more prominent Colonial Administration Building with its offices of the chief executive power, the governor. In other provincial legislative buildings built in the nineteenth century, such as those in Nova Scotia (1819), the Hall of Assembly had a prominent position within the main structure, suggesting the importance of the people’s representatives and the evolving tradition of British responsible government.

Colonial Victoria was different. Not only did the inferior placement of Tiedemann’s Hall of Assembly reflect the actual predominance of James Douglas, the Queen’s representative on Vancouver Island at the time, but it may also have expressed the architect’s own view of the significance of an elected assembly (however limited in power) in civil government. In his experience, the parliamentary system did not exist in the German states where kings and princes still ruled by divine right.

At all events, in 1859 he was commissioned to build the legislative buildings in Victoria. This complex of wooden frame structures consisted of the two-story Colonial Administration Building, flanked by the identical Land Office and Treasury Buildings, with the Court House and the Hall of Assembly to the rear, both also virtually identical, and the Guardhouse.

Even before they were finished, the new government structures inspired ridicule. The Victoria Gazette labeled them “fancy birdcages,” a nickname which endured. Amor de Cosmos wrote that “a traveller placed suddenly among the buildings would consider that he was surrounded by a farmhouse, with an outhouse on each side, and blacksmith shop and two barns in the rear.”[13]

Their hipped, bell-cast roofs, projecting eaves and fretted vergeboards did indeed give them an unusual, almost “Oriental” appearance, but the half-timbered “nogging” of their walls reflected both British and Northern German architectural styles. Moreover, their ground-hugging, wide-verandahed appearance echoed the bungalows of British India, which already had close ties with Victoria.

The main structure, the Colonial Administration Building, two storeys high, seemed both squat and awkwardly looming, compared to its flanking structures. For many Victorians, therefore, the problem was their appearance, at the very least original, but nothing like what mid-nineteenth-century British people thought government structures ought to look like. To some observers the rooflines of these parliament buildings suggested un-British pagodas.

After completing his commission for the new Government Buildings, Tiedemann was involved with the development of the Fisgard Lighthouse, 1859-60, which still stands at the entrance to Esquimalt Harbour.

His precise role in this project is hard to determine: one account notes that he “designed” the whole complex, including both the tower and the keeper’s house, with those structures being “erected by” the contractor John Wright (1830-1915). Another says he designed only the tower while another calls him the “superintendent” of the whole project.[14]

When photography was still in its infancy, the ability to draw and paint accurately — one of Tiedemann’s talents — was essential for the practice, not only of architecture, but also of surveying and engineering. With this skill, he produced a fine panorama, a “View of Victoria,” which shows Victoria Harbour from the west, with the fort and the Birdcages, sailing ships, steamers, Native canoes, and the Songhees village. Executed in 1860, it was reproduced as a lithograph.

Tiedemann also did some surveying in the Victoria area at this time: for example, he laid out the route of a thoroughfare from Saanich Road west to the Burnside area, and surveyed the plat of the city between Pembroke Street in the north and Simcoe Street in the south.

In July 1861, Tiedemann requested from Pemberton a raise in salary, because, although (he said) his duties were mounting, his pay had never been increased in the three years during which he had been employed at the Land Office. It is not clear if he ever received that raise but, if he did not, dissatisfaction with inadequate remuneration may explain his leaving colonial government service on 21 April 1862. From May through August of 1862, he advertised that, having resigned from the government position, he, as a “Civil Engineer and Architect,” sought employment as a surveyor but also providing “plans of buildings, etc. etc.”

At that time, his office was at the premises of another German immigrant, Leopold Loewenberg, a real estate agent on Government Street; by 1863, he was working out of his own premises “next to Nagle’s Shipping Office near the Police Office.”[15] In the same year he applied for the position of City Surveyor but failed to get the job.

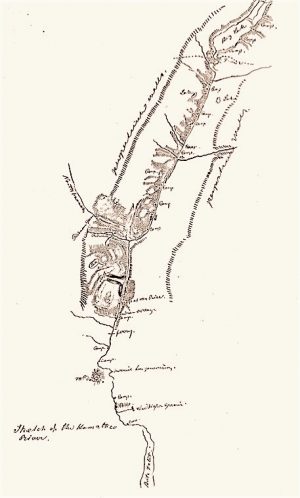

The Birdcages “detracted from his architectural competence,” writes one historian.[16] Perhaps as an architect he was discouraged by public reaction to his work for the government which may explain why in 1862 he accepted employment from the road promoter Alfred Waddington and made his way north by canoe to work on surveys for a wagon route from Bute Inlet through the Homathko Valley to Fort Alexandria in the Interior on the Fraser River, ostensibly a shorter route to the Cariboo gold fields than the one in use.

In this month-long trek, Tiedemann lost his provisions crossing the river, nearly drowned, and, with his companions, “suffered a great deal and starvation was nearly our destiny.” He was “reduced to a skeleton,” suffering from diarrhea, and left emaciated and limping. Perhaps Waddington had underestimated the difficulty of the terrain for the valley had nearly perpendicular walls, surrounded, in Tiedemann’s description, as “far as the eye could reach, nothing else as [sic] Peak, after Peak, thousands of feet in height and clad in perpetual snow.”[17]

Back in Victoria, however, he continued to work as a surveyor, in 1866 planning a dam on the Leech River, near Sooke. In 1863-65, he was active as a cartographer, producing several maps of Victoria and the surrounding district.[18] In 1872, he was surveying again, this time for the Canadian Pacific Railway in the Chilcotin.

The later 1860s seem to have been a barren time for architectural commissions for Tiedemann, due perhaps to the lingering economic depression and to the poor reception of his Government Buildings — or maybe he simply did not seek them. At all events, in October 1867, he advertised that he would teach mathematics and drawing.

He did not lose his commitment to building design, however, for in September 1868 he was demonstrating a method of making walls waterproof by mixing coal oil with mortar. He remained alert to new methods of construction. His offices for the Canadian Navigation Company were said to be built of cement, while his Provincial Law Courts building on Bastion Square was constructed in reinforced concrete.

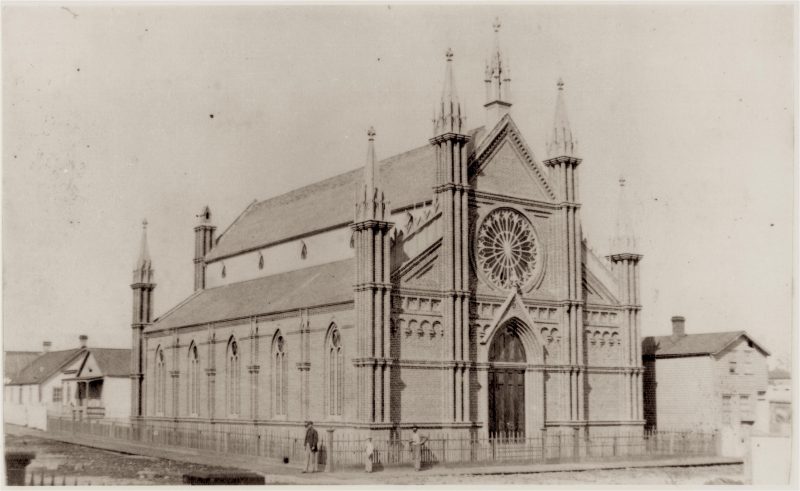

Tiedemann’s St. Andrews Presbyterian Church Victoria, 1869; replaced by a larger structure in 1889-90. BC Archives F-08559.

In 1869, returning to the craft of architecture, he designed the original St. Andrew’s Presbyterian Church, a simple neo-Gothic building on Courtney Street in Victoria, having won a competition for plans over two other contestants. (Despite the census’s designation of him as Lutheran, he and his wife were members of the congregation.)

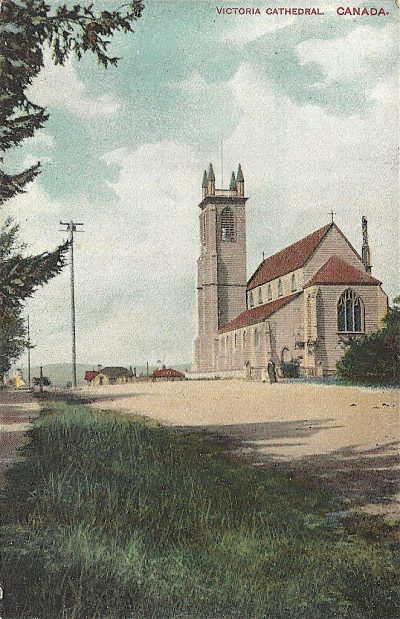

He followed this assignment by designing the Anglican Christ Church Cathedral in 1871-72. Prominently situated on a slope (“Church Hill”) at Blanshard and Burdett Streets, this house of worship, like St. Andrew’s, was in the popular neo-Gothic style.

Tiedemann’s most impressive extant work is the Provincial Law Courts on the site of the former jail and police barracks on Bastion Square. The style, like that of the Birdcages, is eclectic, here uniting Renaissance Revival with neo-Baroque.

The structure is said to resemble the Justizpalast (Palace of Justice or Law Courts) in Munich, Bavaria, but the resemblance is superficial. Moreover, the German structure, designed by Friedrich von Thiersch, was built between 1891 and 1898, so it is not likely that it had much influence on Tiedemann’s structure, built 1888-89 — unless Tiedemann saw the published plans in a newspaper or journal available at Victoria’s “Exchange News and Reading Room.” But this is a remote possibility. As noted above, the Bastion Square structure was one of the first buildings in Victoria to use reinforced concrete. Unfortunately it had flawed acoustics, like those of St. Andrew’s. When Tiedemann’s original Court House (1859) became B.C.’s provincial museum in 1889, many of its furnishings were transferred to his new courthouse where they remain at this writing.[19]

The old Victoria court house has the oldest operating birdcage elevator in North-America, dating back to 1899.

In 1899 the Provincial Court House received an open-cage elevator, still operational today.

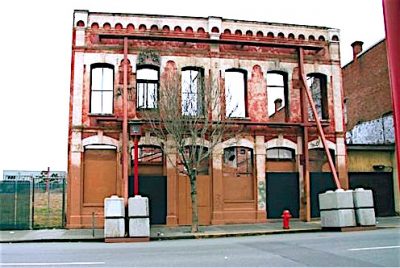

As noted above, much of Tiedemann’s work has been demolished but, other than the Provincial Law Courts and the Fisgard Lighthouse, some of his smaller buildings for local businesses have survived, such as Roderick Finlayson’s Store and Warehouse, both built in 1882.

As a man, Tiedemann seems to have been irritable, hypersensitive, and aggressive. An incident in 1861 could be revealing of his personality as well as suggesting the sort of physical confrontation that could erupt in the early days of Victoria.

A dispute developed over the ownership of 1.13 hectares (2.8 acres) of land 45.7 meters (150 feet) behind the Birdcages’ Court House. Leopold Loewenberg, the real estate agent, claimed that he had purchased the land from the Hudson’s Bay Company. A misunderstanding obviously had occurred because, on 6 May, Pemberton of the Land Office sent men to fence off this area as part of the government precinct.

Tiedemann was supervising the work when Loewenberg showed up with his own men to put up a second fence enclosing the part that he believed to be his. Tiedemann objected, told the men to stop, and started to remove one of the offending fence posts himself, at which time, he claimed, Loewenberg “raised his cane as if to strike me.” The two gentlemen began to struggle over the post. Tiedemann went to get a policeman who later said that he never saw a raised cane or walking stick.

Ultimately, Loewenberg was arrested for trespassing and, having appeared in court on 14 May, was put under a bond to be of good behaviour. As for Tiedemann, he may have overreacted characteristically. In court, he said that he had “none but friendly feelings against Mr. Loewenberg,”[20] which seems to have been the case because by the following year (as noted above) he was renting office space in Loewenberg’s premises.

Tiedemann seems to have had more than his share of self-confidence. Evidence of this trait occurred when, hired in 1864 to survey the Saanich-Burnside Road, he irked his employers by changing the route without consulting them. In that same year, with possibly justified sensitivity, he accused Pemberton of wrongly stating that he had put the latter’s name on a map on which he, Tiedemann, had mislabeled a certain lot.

On the CPR survey, he was said to be over-demanding of his men, perhaps expecting them to endure what he had suffered on the Homathko River survey. An 1867 letter from New Westminster by a travelling Englishmen reads, “Mr. T. appears to be a rather funny man; he ‘guys’ [ridicules] some of the leading merchants here pretty badly.”[21]

In 1874 a bizarre incident occurred concerning the Menzies Street sidewalk near Tiedemann’s home in Victoria. Disliking the amenity, the architect paid $15.00 to have it removed. In 1880 he aroused controversy over his awarding of a contract for the renovation of the Post Office. At this distance in time, the motivations behind and the justice of such incidents are hard to evaluate but Tiedemann does seem to have been a difficult man to get along with.

On the other hand, he was not excessively conservative, for in 1885 he signed a petition to the provincial government asking for the franchise to be extended to women. He adopted his wife Mary’s Presbyterianism and worshipped the St. Andrew’s Presbyterian Church which, as noted, he was hired to design.[22] (He is buried in the Presbyterian section of Ross Bay Cemetery.)

Moreover, he seems to have developed an attachment to Victoria, even feeling a degree of community spirit, becoming active in the city outside his professional circle. In 1864, he was an official “objector” to the petition of John Coe and Thomas Martin to pipe water from Spring Ridge to the city. He feared that passage of the relevant bill would give the Spring Ridge Water Company a private monopoly over the supplying of public water to Victoria. (He later worked as a surveyor on the plans to bringing the first water supply to Victoria from nearby Elk Lake.)

In the 1870s, he was an officer of the local Oddfellows Order. In 1882, he served on the local committee organizing the welcome to the visiting governor general, advising on ceremonial arches and their decoration. In 1891, he was a candidate for the position of Street Commissioner. Intellectually curious, he was a subscriber to the local “Exchange News and Reading Room.”

How good an architect was he? Many of his larger structures came in for criticism. Fellow designer Edward Mallandaine (1827-1905) declared that the wooden foundations of St. Andrew’s Church were too weak for a building that large to rest upon, and that the building was too small a structure for this size of congregation. It is hard to know whether this view was an expression of professional jealousy or an engineering insight.

For their part, the church building committee wanted the neo-Gothic style, and had chosen Tiedemann’s design over two others; but the appearance of the church, Mallandaine thought, was the “rudest travesty of Gothic.”[23] On the other hand, the Presbyterians loved the large front window and, in their official history, maintain that construction proceeded smoothly.[24]

Clearly, some of his buildings had functional flaws, such as the leaky roofs of the Birdcages, but whether these were due to Tiedemann’s faulty designs or to the incompetence of some local contractors is hard to determine. The authorities, for their part, did not cease to grant him contracts, hiring him to report on the structural condition of New Westminster’s Insane Asylum in 1884 and, of course, granting him the contract for the new Provincial Law Courts. In fact, it was the look of some of his structures that most often offended. The Colonial Administration Building of the Birdcages, as noted earlier, made an awkward impression: it was both squat and towered clumsily over the adjacent structures, an additional elevation that, to some observers, had unsuitable connotations.

Christ Church Cathedral, circa 1910. This wooden structure was erected in 1872 and remained functional until 1929.

In photographs and drawings, the modest Christ Church in Victoria looks inoffensive, but John Gerhard Tiarks (1867-1901), an English architect, described the tower as “the most atrocious architectural abortion.”[25] The Daily British Colonist, too, opined that, seen from the west end, the church had “a sort of consumptive look about it.” The journal concluded, however, that “Mr. Tiedemann deserves the credit of having built a good substantial edifice.”[26]

The “bold, handsome elaborate workmanship” of his Hudson’s Bay Warehouse was deemed by the Colonist to mark “a new era in the architectural progress of the city.”[27]

Perhaps the jealousy of underemployed colleagues motivated some of the criticism. Professor Martin Segger sums up the professional rivalries of architects in nineteenth century in Victoria precisely: “informed or un-informed architectural criticism was a blood-sport in the local newspapers, especially led by local architects who thought they should have been given the job.”[28]

*

On 13 August 1861, Tiedemann married Mary (or Marie) Bissett (1834-1898), originally from Lachine, Québec, the sister of James Bissett, a Hudson’s Bay Company employee. By 1863, the couple were living at 45 Menzies Street, near the corner of Superior Street, directly across from Tiedemann’s Birdcages.

Mary and Hermann Otto had four sons, Tudor James, Hermann Bruce, Herbert Alfred, and Oswald Hermann Leopold, the eldest, who died in 1868, aged six years. Tudor James, born 1865, had a successful career in the insurance business, eventually becoming the President of the Fire Underwriters Association of the Pacific in San Francisco. Hermann Bruce, born 1868, was a talented member of the “Wanderers,” a local cycling club, but left Victoria for Toronto in 1893 to learn piano tuning with the Heintzmann Company. Herbert Alfred, born 1875, planned a career as a tenor and studied in California before going to Chicago, where he suddenly died in 1898.

What remains of the once-praised Hudson’s Bay Warehouse. Photo by Victoria Online Sightseeing Tours.

Having been ill with heart disease for some time, Hermann Otto Tiedemann died at his home in September 1891. Fortunately, he did not live to see the demolition of most of his Birdcages in 1897 or his later works in the following years.

In 1893, after Hermann Otto’s death, Mary auctioned off her furniture and other possessions, which may suggest that he did not leave her well provided. She did, however, leave later that year to visit relatives in Montréal whom she had not seen for thirty years. By 1895 she was living at 125 Toronto Street (still in the James Bay area). In 1898, having been ill for several months, she died at 64 years of age in St. Joseph’s Hospital in Victoria. The Tiedemanns’ Italianate-style house on Menzies Street stood until at least 1929.

Whatever his personal qualities or abilities as an architect, as a surveyor Hermann Tiedemann was respected. Near the site of his surveying work in the province’s interior, Mount Tiedemann, the Tiedemann Glacier at the head of Bute Inlet, and Tiedemann Creek are named in his honour. In Victoria, Tiedemann Place off Ferndale Road in Gordon Head also bears his name.

The history of early Victoria has several examples of vivid “characters” such as Tiedemann. He was, of course, never as flamboyant as Amos de Cosmos or as unhinged as George Hunter Cary. Despite his shadowy origins and difficult personality, Hermann Tiedemann flourished in a turbulent period of B.C.’s history and left his mark on Victoria’s Bastion Square.

*

Robert Ratcliffe Taylor was born and raised in Victoria, B.C. and attended Willows School, Oak Bay Junior and Senior High Schools, and Victoria College. He has a B.A. in English and History from U.B.C., an M.A. in History from U.B.C. and a Ph.D. in History from Stanford. He taught History at Brock University in St. Catharines, Ontario, where he was active in the Local Architecture Conservation Advisory Committee, the Welland Canals Preservation Association and the Canadian Canal Society. He has published in German history, St. Catharines history, and, with Dr. R.M. Styran, the history of the Welland Canals. “Retiring” to Victoria, he has worked as a Docent at the Victoria Art Gallery and has published books and articles on local history. This article on Tiedemann is part of his research into the “Birdcages,” British Columbia’s first legislative buildings. He and his wife Anne have one son, John, two grandsons, and three great-grand-children.

*

[1] R. Windsor Liscombe, “TIEDEMANN, HERMANN OTTO,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 12, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed November 25, 2017, http://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/tiedemann_hermann_otto_12E.html.

[2] Some controversy surrounds the architect’s birthplace but his obituary (Victoria Daily Colonist, 13 September, 1891, 5; hereafter cited as Colonist), presumably written by a knowledgeable family member, asserts that he was a “native of Berlin.”

[3] BCARS, Colonial Correspondence, B 01367, Box 130, File 1703.

[4] BCARS, B 16901, Box 1, File 6.

[5] A bizarre meeting in New York City with a Victoria man whom Tiedemann had presumed to be dead was recounted by Judge Eli Harrison much later. (Colonist, 11 November 1928, 2.)

[6] Surveyor-General Joseph Despard Pemberton’s previous role as an HBC employee, may have predisposed Douglas, the Company’s former Chief Factor, to accept his judgement in many matters. On Pemberton’s career, see Richard Mackie, “PEMBERTON, JOSEPH DESPARD,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 12, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed November 25, 2017, http://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/pemberton_joseph_despard_12E.html.

[7] BCARS, Colonial Correspondence, B 01367, Box 130, File 1703.

[8] In mid-nineteenth-century in North America, civil engineers often practiced architecture and surveying, although they were usually self-defined as civil engineers. Even after Tiedemann had completed the designs for the Birdcages and other buildings, the local voters lists for 1875 and 1883 define him as a “Civil Engineer.” Between 1863 and 1887, the city directory describes Tiedemann as either an architect or a civil engineer.

[9] Colonist, 26 August 1859, 3. De Cosmos’ disapproval of Governor James Douglas’ authoritarian ways partly explains his damning criticism of the Government Buildings, the construction of which Douglas had himself inspired.

[10] See Richard Mackie, “PEARSE, BENJAMIN WILLIAM,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 13, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed November 25, 2017, http://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/pearse_benjamin_william_13E.html.

[11] This letter as well as his Bute Inlet Report and the Journal are at BCARS, GR 1372, F903/26 and BCARS, E/B/T44.

[12] See W. Kaye Lamb, “WADDINGTON, ALFRED PENDERELL,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 10, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed November 25, 2017, http://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/waddington_alfred_penderell_10E.html.

[13] Victoria Gazette, 20 September 1859, n.p.; Colonist, 20 July 1859, 2.

[14] Colonist, 9 June 1860, 3; BCARS, “Account of the Lighthouses,” B-16918, 13 October 1859.

[15] Colonist, 16 February, 1863, 3.

[16] See Windsor Liscombe, “TIEDEMANN, HERMANN OTTO,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 12.

[17] Tiedemann’s Report to Waddington and Journal, July 1862. (BCARS E/B/T44A)

[18] His maps are cataloged in Richard Ruggles’ A Country So Interesting. The Hudson’s Bay Company and Two Centuries of Mapping 1670-1870. (Montreal/Kingston: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 1992.

[19] Correspondence with heritage consultant Stuart Stark, 3 March 2017.

[20] Colonist, 8 and 14 May 1861, 3.

[21] “J.R.A.B.”, Colonist, 12 August 1867, 2.

[22] The First Presbyterian Church, on Pandora Avenue (founded 1862), occasionally held services in German, so possibly Tiedemann also worshipped there from time to time. (e.g. Colonist, 22 January, 1888, 4).

[23] Colonist, 29 March 1869, 3. See also Edward Mallandaine’s bitter reaction to his failure to get the contract for an addition to the Birdcages’ Central Block (BCARS MSS 470, Box 1).

[24] Session of St. Andrew’s Presbyterian Church, The Kirk that Faith Built. St. Andrew’s on Douglas Street, Victoria: Morriss Printing, 1989, 14.

[25] Quoted by Chris Hanna and Mary Doody Jones, in Donald Luxton, ed., Building the West. The Early Architects of British Columbia, Vancouver: Talon, 2007, 168.

[26] Colonist, 20 October, 1872, 3. That aforementioned travelling Englishmen praised his Holy Trinity Anglican Church in New Westminster, which “does him great credit.” (J.R.A.B, Colonist, 12 August 1867, 2.)

[27] Colonist, 28 May 1884, 3.

[28] Correspondence with Professor Martin Segger, 1 November 2016.

A stereoscopic view of a military band at the Birdcages, circa 1870s. Richard Maynard photo. Wayfarers Bookshop.

The Ormsby Review. More Readers. More Reviews. More Often.

Reviews Editor: Richard Mackie

Reviews Publisher: Alan Twigg — BC BookWorld / ABCBookWorld / BCBookLook / BC BookAwards / The Literary Map of B.C. / The Ormsby Review

The Ormsby Review is a new journal for serious coverage of B.C. literature and other arts. It is hosted by Simon Fraser University. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Robin Fisher, Cole Harris, Wade Davis, Hugh Johnston, Patricia Roy, David Stouck, and Graeme Wynn.

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

Just to clarify, in 1872 Tiedemann led CPR survey Party W from Bute Inlet up the Homathko River to the Chilcotin Plateau. See the “Colonist” report of his departure from Esquimalt on HMS “Scout”; June 15, 1872, p. 3.

At age 54 in the summer of 1875, Tiedemann returned to the Homathko River to lead a trail-building crew as part of the CPR survey work along the Bute Inlet (Homathko River) route.