#103 Tainted blankets, tainted history

March 13th, 2017

REVIEW: The Smallpox War in Nuxalk Territory

by Tom Swanky

Surrey: Dragon Heart Enterprises, 2016

$39.95 / 9781365410536

Reviewed by Courtney Kirk

*

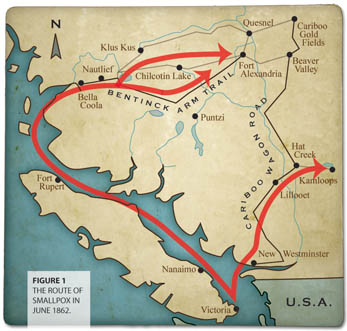

In 1862, colonial officials, supported by merchants, surveyors, and road builders, concocted a get-rich-quick scheme to link the coast of B.C. at Bella Coola to the gold fields of the Cariboo.

The only problem, asserts Tom Swanky, was that Nuxalk people and territory were in the way. In The Smallpox War in Nuxalk Territory, Swanky argues that, to make the road a reality, powerful groups of colonial official and settlers “repeatedly and systematically created artificial epidemics in Nuxalk territory.”

Swanky believes the “responsibility for this intentional mass killing can be traced to the administration of Governor James Douglas and especially to Attorney General George Cary.”

He provides arguments to support his view that a policy of smallpox-induced genocide gave government and speculators unfettered access to Nuxalk (previously Bella Coola) territory and a blank slate to impose British institutions without Nuxalk consent.

Reviewer Courtney Kirk assesses the role of an extensive and covert old boys’ network with business and kinship ties to the Hudson’s Bay Company that allegedly cold-bloodedly depopulated Nuxalk territory for the benefit of colonial officials, merchants, and other settlers. – Ed.

*

I cannot seem to find words strong enough. With each conversation I’ve had summarizing Tom Swanky’s The Smallpox War in Nuxalk Territory in preparation for this review, I’ve found myself incapable of communicating the dismay I felt as I followed him down the rabbit hole.

I read The Smallpox War twice. I took notes. I found Swanky’s narrative of egregious breach of public trust by Governor James Douglas’s regime in the founding years of what is now British Columbia so distressing that I explored his earlier and more expansive The True Story of Canada’s “War” of Extermination on the Pacific plus The Tsilhqot’in and other First Nations Resistance (2012), and I took notes on that book too.

But that still wasn’t enough. I turned to the internet for scholarly biographies and conventional historical portrayals of the accused, including James Douglas, Robert Burnaby, Captain Cavendish Venables, Attorney General George Hunter Cary, and Francis Poole, to name a few of the men about whom Swanky’s provides informed yet startling new historical interpretations.

I thought about who these men and their collaborators were, who they have been depicted to be, and the accolades that immortalize their work in early B.C., particularly the physical memorials: the street names, the municipalities, the schools, the parks, and the waterways.

I contrasted those common narratives with the evidence Swanky mounts against colonial merchants and prospectors, politicians and authorities, and those labouring for the wealthy and powerful, such as surveyors and road builders. Swanky reveals that a significant number of these individuals had ties to the Hudson’s Bay Company. He emphasizes the familial, fraternal, and corporate entanglements that appear to compromise the actions of so many officials of the colonial era in B.C.

Through his revelations sourcing the written colonial record while respecting specific First Nations’ oral histories, Swanky demystifies how, within a mere decade or so of exercising what should have been relatively limited Crown authority, B.C.’s first colonial officials managed to set the stage for some 150 years — and counting — of irreconcilable land, water, air, and resource disputes between many First Nations and the Crown.

Swanky exposes the startling extent to which the Douglas regime exercised declaratory, regulatory, and/or spending power to further private gain. To identify abuses of public power for private gain, Swanky walks his readers through who held what interest in various corporations and land prospects.

Yet that wasn’t what kept me up at night. Years of study devoted to constitutional and Indigenous rights law, as well as privileged access to Nuxalk perspectives on historic and contemporary Crown oppression tactics, prepared me for most of Swanky’s revelations on the depth of the Douglas regime’s public misfeasance.

I knew that smallpox was the centrepiece of his study, and I anticipated that I would learn of some wayward, overzealous, or deranged official(s) deliberately spreading the disease from an independent motivation..

What I wasn’t so prepared for was Swanky’s evidence of an elaborate and far-reaching “get rich quick scheme” that was contingent on an executive design, orchestrated by George Hunter Cary, Douglas’s Attorney General, for land and toll road rights of way between Bella Coola and Quesnel — a route that was intended to be part of a new northwest passage by land.

This land was wholly occupied and governed by First Nations, including Nuxalk people. Swanky argues that the Attorney General himself was set to be a primary beneficiary of the scheme, a significant piece of the puzzle implicating the Crown in a pressing and substantial private objective of genocide.

Overwhelmed by the suggestive darkness, I wondered how deep the well might go as I tumbled down through Swanky’s well-researched analysis: he supports his arguments with 450 footnotes in The Smallpox War and nearly 1,000 endnotes in The True Story, the culmination of his ten-year research odyssey.

His synthesis dovetails legislative and public archives, memoirs, and newspaper articles covering the period under review, as well as pertinent case law, legislation, scholarly works and hundreds of hours listening to impacted First Nations’ oral historians. Swanky mounted his broad charge of genocide against the Douglas regime in The True Story and now narrows his analysis to the Nuxalk in The Smallpox War.

Given his legal training and expertise in political philosophy, Swanky’s style is reminiscent of an elaborate legal argument. The “organizing thread” of The Smallpox War, as he puts it, “is the origin of the constitutional relationship between Canada and the Nuxalk” (p. vii). Rather than rely in any great depth on the narratives, conclusions, and interpretations of other historians, he offers his own interpretation of the documentary record, which involves his identification of pertinent historical facts analyzed against governing legal standards and principles.

Some readers may not be familiar with concepts like “the honour of the Crown” (ch. 3), where Swanky provides important legal context about the significance of his research to current constitutional conversations, but most will recognize ideas like “premeditation” and “intent” (pp. 116-7) when Swanky walks us through the culpability of some of his key accused.

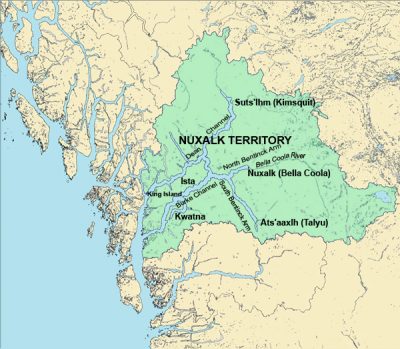

As a historian, Swanky offers a condensed survey of the documentary record organized by topic; as legal scholar, he provides context through the use of legal principles and contemporary reflections on precedent. His timeline, which he provides as an addendum (pp. 194-208), is very helpful in keeping track of the chronology of events. I also found the maps and graphics by Swanky’s son, Shawn Swanky, useful in visualizing the official ambitions that Swanky describes (pp. 178-191).

Though potentially a shocking reality check for Douglas apologists, The Smallpox War may not prove a shattering revelation to many First Nations, particularly those most directly afflicted by the epidemics induced by road builder Francis Poole and the cascade of settler exploitation that followed – and that continues.

Swanky relates that Elders had “discussed these smallpox epidemics extensively [within the Nuxalk Nation] and … it was common knowledge in their community that the disease had been introduced intentionally to kill them as a People; that is, in acts of genocide” (p. 47 footnote 88).

Yet the corroborating written historical record identified by Swanky may be extremely important evidence in future restitution conversations between afflicted First Nations and the Crown, and indeed his research has already had some practical political results. His first expose of the Douglas regime in The True Story was followed by an apology offered to the Tsilhqot’in Nation by Premier Christy Clark on behalf of the B.C. legislature. Exonerating the martyred Tsilhqot’in chiefs, whose struggles to protect their people from malevolent settlers are covered in depth in Swanky’s The True Story, Premier Christy Clark stated that:

Today we acknowledge that these chiefs were not criminals and that they were not outlaws. They were warriors, they were leaders, and they were engaged in a territorial dispute to defend their lands and their peoples…. I stand here today in this Legislature, 150 years later, to say that the province of British Columbia is profoundly sorry for the wrongful arrest, trial and hanging of the six chiefs and for the many wrongs inflicted by past governments. (Ministerial Statements, “Reconciliation with the Tsilhqot’in Nation”, BC Hansard, Oct 23, 2014 at 4860-1).

Those many wrongs the Premier apologized for include the deliberate spread of smallpox, which Swanky substantiated through his analysis of the written record. As the Premier detailed in the same ministerial statement:

After the colony of British Columbia was established, Tsilhqot’in lands were declared open for access, without notice or without effort at diplomacy. Many newcomers made their way into the Interior. Some of them came into conflict with the Tsilhqot’in, and some brought with them an even greater danger. That was smallpox, which by some reliable historical accounts there is indication was spread intentionally. (Ministerial Statements, “Reconciliation with the Tsilhqot’in Nation”, BC Hansard, Oct 23, 2014 at 4860).

While the premier of B.C. has acknowledged that there are reliable historical accounts of smallpox being spread deliberately, it remains to be seen what the ripple effect will produce as British Columbians — the settler-state beneficiaries of the actions Swanky recounts — come to terms with the implications of his work. Like tsunamis waves with a causal epicentre an ocean away, time and depth of analysis will be the predictor of the scale of impact.

To put the ground-changing potential of Swanky’s work into context, consider that none of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada, the Royal Commission on Aboriginal Peoples, the Supreme Court of Canada, or the many Crown entities and servants tasked with the goals of reconciliation, have offered any substantial reporting on how the B.C. smallpox epidemics came to be in the first place. We’ve all been awash in a creation myth that suggests First Nation loss of life to the disease was an inevitable natural disaster.

In the “smallpox natural disaster narrative,” it doesn’t really matter whether it’s possible that a few unscrupulous settlers may have deliberately exposed First Nations to the disease, and even going so far as to trade with infected blankets, or whether the exposure happened through unwitting carriers.

Either way, in the smallpox natural disaster creation story, the Crown is unburdened with culpability for the scale of deaths that followed because those deaths are generally regarded as the result of “inferior” First Nation resistance to settler imported diseases.

Therefore this creation story is most favourable to the beneficiaries of spaces of land and water that had been suddenly depopulated by the smallpox “natural disaster.” To those beneficiaries, the lack of effective Indigenous resistance — owing to depopulation — to unrelenting resource extraction and to colonial rules was an auspicious accident furthering settler ambitions for British Columbia.

At the very worst, in this favoured creation story, settlers merely watched Indigenous peoples die, and then condescendingly set out to indoctrinate the survivors in the colonists’ “superior” ways while simultaneously, and ever after, depriving First Nations of their territories and waters.

And this particular creation story continues to carry great power. Most contemporary restitution conversations impacting Pacific shelf First Nations focus on Crown actions that followed the epidemics, such as a recent focus on the residential school era, and not on the initial role the Crown played with respect to the epidemics themselves.

And yet, as Swanky suggests, it is doubtful that much of the genocidal history that followed on the Pacific shelf would have been permitted by the Indigenous populations but for the debilitating, concentrated loss of life that First Nations suffered during the Douglas regime.

As matters stand, few political or legal conversations focus on the role of smallpox in ushering in Crown sovereignty in the many First Nation territories now collectively known as British Columbia. Tom Swanky has given me pause to consider the remarkable assault on the principles of equity in assigning “radical or underlying title” to the Crown in Aboriginal title territories where, as it turns out, the Crown asserted control only after the vicious slaying of thousands of Indigenous citizens who were in the way of a covert, officially driven, property inflation scheme.

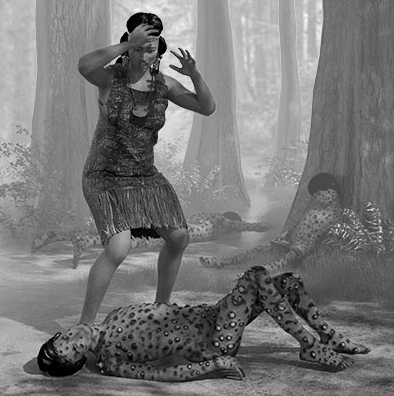

As I descended down with Swanky into this ever-darkening account of the period, I couldn’t resist doing my own research on the physiological impacts of smallpox, such as the debilitating fever and pain and the horrific all-encompassing skin blisters that begin in the throat and spread all over the body.

I looked first at Shawn Swanky’s illustrations on the cover, and then at archive images accessible through Google Search that include afflicted children and the elderly with bodies ravaged by the telltale fluid-filled indented pox that will eventually scab. I was horrified by the visual condition of smallpox, which rivals even the wretchedness conveyed in artistic representations of imaginary zombies.

I thought about the many stories I’d been told over the years of Nuxalk Ancestors practicing epidemic suppression through isolation: Ancestors who literally crawled away from their families and loved ones into caves and recessed places in the woods to die, to protect others from contracting the sickness.

I appreciate the care Swanky took to validate those histories of First Nation disease management (pp. 124-6) as he marshals evidence that both the rate of disease progression and the final death tolls of the Nuxalk smallpox epidemics indicate deliberate and methodical exposure (pp. 126-131).

I was troubled by the eyewitness accounts Swanky shares of the Nuxalk experience contained in the written record that vividly illustrate the brutal scale and horror of the death. We learn from Lieutenant Henry Spencer Palmer of the Royal Engineers that, in an epidemic still in its very earliest stages and where only one or two deaths should have been expected, “[n]umbers were dying each day; sick men and women were taken into the woods … to die by themselves and rot unburied….” And in his private observations to Colonel Moody, Palmer elaborated that “… they are dying and rotting away by the score, and it is no uncommon occurrence to come across dead bodies lying in the bush….” (p. 129).

These first hand observations, and others Swanky recounts, continue to haunt me. Even now, as I stare out my kitchen window, I wonder with a shudder how many Ancestors passed where my children play in the wooded terrain around our home.

The stories of the smallpox blankets haunt me too. At a presentation given by Swanky when introducing The Smallpox War to the Nuxalk College, I learned of a historic account of methods used to infect blankets. Swanky related a Tsilhqot’in narrative that skins of deceased smallpox victims were flayed in order to extract diseased pox. The skin was then surreptitiously folded into trading blankets. When a recipient opened the blankets, the flayed skin would fall out, sometimes leaving an impression that snakes had crawled through the blankets.

Tom Swanky has exposed those snakes for what they were and, in the process, has excoriated British Columbia’s creation myth. As scholarly contributions, The True Story and The Smallpox War will find greater traction among specialized readers owing to the sheer amount of complex and overlapping information provided, but these books will also be rewarding for general readers and especially for those employed in reconciliation endeavours between British Columbia and First Nations.

The Latin maxim “you cannot give what you do not have” (nemo dat quod non habet) is as old a guiding principle as Western property law itself. That is, the purchase of something from someone who does not own it also denies ownership to the purchaser. Similarly, the “sorrowful trail of blood” left by Francis Poole in his wake (p. 108) contaminates all settler activity that followed. Douglas’s legacy is an entire province awash in ill-gotten gains, a colonialist project that should invest every citizen in B.C. in an urgent dialogue.

Fortunately, Tom and Shawn Swanky are collaborating on a documentary to share this critical history with a broader audience (see the ShawnSwanky.com website), because in Swanky’s words, “[u]ntil one knows how and why the previous course was set, one cannot be sure of any new tack” (p. 7).

*

Courtney E. Kirk is a constitutional law critic specializing in Indigenous rights and emergency management regimes. Her formal education includes a Bachelor of Laws (Juris Doctor) and a Master of Laws earned at the University of Saskatchewan, as well as a Bachelor of Science earned at the University of Calgary. Courtney currently teaches at Nuxalk College located in the area now commonly known as the Bella Coola Valley on the central coast of B.C., a beautiful portion of spectacular Nuxalk Ancestral Territories.

*

The Ormsby Review. More Readers. More Reviews. More Often.

Reviews Editor: Richard Mackie

Reviews Publisher: Alan Twigg

The Ormsby Review is hosted by Simon Fraser University. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Cole Harris, Wade Davis, Hugh Johnston, Patricia Roy, David Stouck, and Graeme Wynn.

—

BC BookWorld

ABCBookWorld

BCBookLook

BC BookAwards

The Literary Map of B.C.

The Ormsby Review

here’s another maxim for British Columbians.. “as you sow, so shall you reap”.

y’all are in for a miserable future.. the Onkwehonwe judiciary/enforcement institutions may operate quietly in recent decades, but we are here, in every city across A’nó:wara tsi kawè:note, ready. Post-earthquake time in BC will be an interesting op.. better hope your geo-scientists are wrong 😀

This and similar stories of my ancestors’ brutality, ignorance, greed and self-deception fill me with shame and sadness. My only hope is that future generations will give as much credence to aboriginal accounts of these genocidal attacks as past generations have given to the power-mongers who perpetuated them in the first place. Thanks for the review.