Modernism at home in B.C.

Among the architects who changed home design in the 1940s and 1960s were C. E. 'Ned' Pratt and Bert Binning.

November 25th, 2014

Bert and Jessie Binning's 1941 home is considered the first "modern" West Coast house.

The West Coast Modern House (Figure.1 $45) chronicles how ground-breaking pioneers in Vancouver created one of Canada’s most important architectural movements.

by Beverly Cramp

At the end of World War II, service men and women returned to North America to begin life anew. It was a time of rebuilding and making up for lost time after ten years of the Great Depression followed by five years of war shortages.

Pent-up demand fueled a housing boom, a baby boom and a growth economy that continued with only minor interruptions for several decades. Such optimistic conditions often foster innovation and creativity.

Pent-up demand fueled a housing boom, a baby boom and a growth economy that continued with only minor interruptions for several decades. Such optimistic conditions often foster innovation and creativity.

Nowhere was this creative surge more evident in British Columbia than in its architecture profession. Practitioners changed the shape of houses, as well as landscaping ideas, creating a style that came to be known as West Coast Modernism, especially evident in residential design.

The West Coast Modern House, edited by Greg Bellerby, explores B.C.’s architectural renaissance and suggests it was ahead of the rest of the country. Essays are contributed by Bellerby, Chris Macdonald and Jana Tyner, and a reprinted article by early architectural innovator C.E. (Ned) Pratt is included.

It is virtually impossible to state precisely what a West Coast Modern House style is and instead general principles are described, such as: extensive use of local materials (e.g. cedar wood and stone sourced from nearby locales); respecting the site and using the natural characteristics to influence the design, which meant not bulldozing the property flat and cutting down as few trees as possible; often using lots of windows to let in natural light; creating open plan interior spaces for free flow of air and light; integrating the outdoor spaces with the internal house spaces; and applying a whole new approach to landscaping gardens.

One early feature was the implementation of ‘flat’ roofs, a completely different form from the ubiquitous pitched roof. So radical was this concept that initially banks refused to mortgage houses with these designs.

Most eye-opening is C.E. (Ned) Pratt’s re-printed essay in which he reveals that he and his colleagues actually had to convince their clients to accept the new style concluding that, “these houses represent untiring efforts on the part of architects to persuade the client into the contemporary frame of mind.”

Pratt writes of an amusing incident when one of these new homes was being photographed. A neighbour approached the photographer to say that, “he could not understand why a photograph should be taken of a ‘cow shed’.”

Editor Greg Bellerby spent six years producing The West Coast Modern House. He was born in Vancouver, studied at the Vancouver School of Art and was a curator and director of the Charles H. Scott Gallery at the Emily Carr University of Art + Design. Ideas for this book were formed when Bellerby was the commissioner and co-curator of the Canadian Pavilion at the 2006 Venice Biennale of Architecture.

The idea of “Modern Architecture” started in Europe in the early years of the 20th century. The Bauhaus movement was a big proponent. Canadians visiting Europe during those years in the 1920s and 1930s were exposed to these notions. As well, European architects uprooted by the pre-World War II politics relocated to America where they spread the aesthetic.

“Austrians Rudolf Schindler and Richard Neutra arrived in the early 1920s and settled in California,” writes Bellerby. “Walter Gropius was appointed Chair of the Harvard Graduate School of Design in 1937, and Marcel Breuer soon followed. Ludwig Mies van der Rohe came to the U.S. in 1937 to head up the architecture department at the Illinois Institute of Technology, and Finnish architect Alvo Aalto was invited to teach at MIT in 1941.”

Bellerby includes in his list the American genius, Frank Lloyd Wright, who was working in isolation from the Europeans but who contributed to Modern Architectural ideals. “American Frank Lloyd Wright was also a major influence in the 1930s and through the post-war era. The work of these architects would have been known in Canada and the West Coast through publications circulating at the time. [Vancouverite] Fred Hollingsworth speaks about first becoming interested in architecture after seeing an article on the work of Frank Lloyd Wright during the war.”

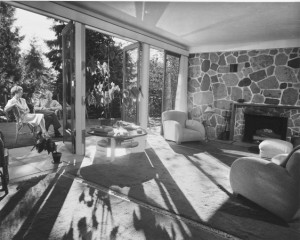

Another important figure in the West Coast Modern scene was artist B.C. Binning, who also taught at UBC’s School of Architecture. “The house B.C. Binning designed for himself and his wife Jessie in 1941 has been cited as the first modern house in Vancouver. Binning, who was also an artist and teacher, brought his artistic temperament and his recent travel experiences in England and New York to the task of designing his home.

“The house included many attributes that have since become typical of the West Coast modern style: it is sited facing away from the street and towards a view of the south; it follows the slope of the lot and the entrance is reached through a terraced garden; it has a flat roof and clerestory windows bringing light into the central core; and the living room has a series of French doors that open onto a generous terrace.”

In this early West Coast Modern house, Binning invited visiting artists and architects to mingle with his UBC students, including Richard Neutra who came to lecture in 1946 and again in 1953.

Shortly before Binning built his landmark modernist house, in 1937, two newly-graduated architects – Charles E. (Ned) Pratt and Robert Berwick – joined the firm Sharp & Thompson and transformed it toward modernist ways of design thought.

“One of the most important architectural firms to contribute to the development of Vancouver’s modernist era was Sharp & Thompson, Berwick, Pratt,” writes Bellerby. By 1955 the firm renamed itself Thompson, Berwick & Pratt. “The firm was one of the busiest in the city and, post-war and during the 1950s, it became an incubator for the West Coast modern style… The firm apprenticed and employed many individuals who contributed to Vancouver’s unique brand of modernism. Pratt was an inspiration to younger staff, encouraging creative thinking and experimentation with building techniques, which he then applied to the design of his own home. He also supported experimentation by Ron Thom and others.”

In fact Thom and another apprentice, Fred Hollingsworth, went on to become significant contributors to residential architecture in Vancouver. Around this time a young upstart named Arthur Erikson began his career designing houses and many believe he took it to its apex when he built Smith House II for painter Gordon Smith and his wife Marion.

Lesser known but equally significant is the landscaping that evolved alongside the West Coast Modern home. An essay by architectural historian Jana Tyner seeks to link the “architectural product of this time – the post-and-beam house built of local cedar with wide overhangs and large bands of glass” to local innovations in landscape. Both architects and landscape designers of the time, “believed that landscape design, when considered a component of the built environment, could encourage interaction between people and their sites. In their view, the “rooms” of a residential garden – created through the outdoor arrangement of materials and plantings – should be designed with the same degree of rigour and care as the house itself.”

One of the experimental landscape architects that emerged during this period was Cornelia Hahn Oberlander. She was an early proponent that “landscape and building had a direct connection with the overall health and well-being of its occupants.”

Oberlander believed that a garden should be functional as well as attractive. Tyner describes the garden she designed for a busy Vancouver professional couple: “Oberlander replaced the traditional lawn with swaths of raked gravel, and bordered the site with evergreen (and intentionally regionally indigenous) juniper, laurel, euonymus, and Andromeda. This ensured a self-sustaining garden, which accorded with Oberlander’s penchant for Bauhaus functionalism.”

Oberlander herself best encapsulated her minimalist and austere style, strictly limiting the number of different plants when she said: “What I love about Bauhaus is that it is very functional, very abstract, very simple… The visual impact is in the quantity of things. Mixing a whole bunch of plants is like wearing five polka-dot dresses at the same time. You can’t see the design.”

Contemporary house by Patkau Architects, second generation designers of the West Coast Modern style.

The West Coast Modern House is full of large photographs, mostly black & white, of Vancouver’s ground-breaking houses from the 1940s through to the mid-1960s. It also includes later contemporary buildings that have been influenced by the early innovators. A second and third generation of designers including Peter Cardew, the Patkaus, Jim Cheng and Bing Thom (the second generation) as well as firms such as BattersbyHowat, D’Arcy Jones Architects and CamposLeckie (the third generation) ensure that modernist values continue.

“The persistence of the modern house attests to the values embraced by post-war architects… Greg Bellerby concludes. “That these values have endured and continue to find relevance in contemporary residential architecture confirms that modernism is not an historical moment, but that modern concerns will continue to be examined, adapted, and allowed to evolve.” 978-1-927-958-23-0

Leave a Reply