True tales of Camelsfoot

Judith Plant's memoir of a commune named Camelsfoot in the Yalakom Valley, built in 1976, abandoned by the mid-1980s, probes what went wrong and what was learned.

July 25th, 2018

Lessons learned at the Camelsfoot commune continue to inform Judith Plant's decisions.

The failed dream is a common trope in back-to-the-land memoirs — but Culture Gap shows that much can be learned from an experiment gone awry.

Culture Gap: Towards a New World in the Yalakom Valley

by Judith Plant

Vancouver: New Star Books, 2017.

$19 / 9781554201334

Reviewed by Nancy Janovicek

*

What had happened to us? Where did it go wrong? What could we have done? What should we have done? What we built together had seemed so right, so authentic, so much of our own making, so important in the whole scheme of things, so vibrant. Our lives were in our hands. It was so thrilling that we were blinded by the trajectory of our downfall – Judith Plant.

What had happened to us? Where did it go wrong? What could we have done? What should we have done? What we built together had seemed so right, so authentic, so much of our own making, so important in the whole scheme of things, so vibrant. Our lives were in our hands. It was so thrilling that we were blinded by the trajectory of our downfall – Judith Plant.

Culture Gap is Judith Plant’s memoir about the Camelsfoot commune. In 1976, an idealistic group of hippie philosophers followed Fred Brown, their professor and mentor, and his partner Susan to the Yalakom Valley near Lillooet to create an intentional community. Plant and her family joined Camelsfoot in 1982. Like many social experiments of its kind, it did not last. Communards began to leave when Fred died in 1983 and within a few years the community was abandoned. The passing of Susan in 2013 and a reunion of friends for the celebration of her life inspired Plant to write this book. Walking through the abandoned buildings stirred melancholic memories of lost ideals, friendships, and dreams of community.

The failed dream is a common trope in back-to-the-land memoirs — but Culture Gap shows that much can be learned from an experiment gone awry. Often in memoirs, these experiments are portrayed as youthful fads doomed to fail. Sometimes these memoirs are a nostalgic recounting of a carefree youth and sometimes they are cynical accounts written by children forced to follow their parents’ dreams. Plant does not fall into this trap. Culture Gap is a thoughtful reflection on the political climate of the 1970s that compelled people to seek out bucolic spaces in which to build an alternative to urban overcrowding, pollution, overconsumption, and exploitive capitalist relations.

Plant entered these politics as a single mother who had returned to university. She attended Simon Fraser University and fell into the circle of students drawn to Fred Brown’s radical ideas. He railed against institutionalized caring and bureaucratic social networks that had replaced a true sense of collaborative community in modern society. He taught his students that the only way community could be achieved was by returning to culture and by reorganizing society into de-centralized social movements. This could only be achieved in intentional communities that rejected technocratic solutions to the world’s problems. Brown’s teachings continued outside of the classroom during late night discussions about building community and living intentionally, first at students’ apartments and then at his own communal house. Informed by the philosophy of John Dewey and George Herbert Mead, they not only imagined a new world, they set out to build it.

They chose an abandoned adventure camp only accessible by a mountain pass, which was easier to walk than to drive, as the site for their new home. The trek to Camelsfoot, in the Yalakom Valley north of Lillooet, was a literal and symbolic step toward their back-to-the-land experience. The book takes its title from a steep gorge that Brown dubbed the Culture Gap because it marked the divide between the old and new world. “It took courage to reach the other side, the new world. And it’s dangerous,” Plant writes. “You know as soon as you see it that it could take your life if you’re not completely paying attention” (p. 6). Careful passage required attention, as did building a community committed to “changing the world through the actions of our lives” (p. 101).

Work was central to building the community, which sought to be self-sustaining, work that was joyful because they were building an alternative to the mainstream. Every morning began with a discussion about the tasks to be completed that day and the division of labour. Most work hours were dedicated to feeding the group, foraging, hunting, gardening, building an orchard, and raising and slaughtering livestock. Provisions from the Fed-Up Co-op, a volunteer-run food co-operative in Vancouver, which also served as a vital link among rural and remote intentional communities, supplemented what could not be produced on the land. Construction of their own hydroelectric project so that they could live off-grid demanded everyone’s time. Thinking was important work, too. Everyone was allocated days to read, write, and engage with progressive politics outside of the commune.

This idyllic life was not conflict free. While they shared a commitment to building an intentional community, they disagreed on how this should be achieved. Tensions between “Realos” and “Fundis” (pragmatists and fundamentalists) were tangled with debates about goats versus cows. Plant remains uncertain why a commune built by like-minded folk unraveled, but the incessant attention to renegotiating relationships combined with entrenched ideas about how to build the new world eventually took its toll. Moreover, Fred seems to have been the glue that held them together.

Fred Brown was born in 1914 and raised in rural Wyoming. His life-long political engagement with intentional communities was the foundation of Camelsfoot. Contrary to popular cultural portrayals, the back-to-the-land-movement was not the brainchild of disillusioned hippies seeking authenticity. These 1960s and 1970s communes were part of a longer tradition of people moving from urban to rural environments to live alternatively. In my own research on the back-to-the-land movement in the West Kootenays, those who moved to the region as young urban refugees relied on the wisdom of Doukhobors, Quakers, and older radical thinkers who had experience living rurally. Brown had connections to the early “new homesteaders” in the West Kootenays, in particular David Orcutt, who mentored a new generation of back-to-the-landers to the region.

Fred Brown was born in 1914 and raised in rural Wyoming. His life-long political engagement with intentional communities was the foundation of Camelsfoot. Contrary to popular cultural portrayals, the back-to-the-land-movement was not the brainchild of disillusioned hippies seeking authenticity. These 1960s and 1970s communes were part of a longer tradition of people moving from urban to rural environments to live alternatively. In my own research on the back-to-the-land movement in the West Kootenays, those who moved to the region as young urban refugees relied on the wisdom of Doukhobors, Quakers, and older radical thinkers who had experience living rurally. Brown had connections to the early “new homesteaders” in the West Kootenays, in particular David Orcutt, who mentored a new generation of back-to-the-landers to the region.

I read this book in tandem with Van Andruss’s 2012 biography of Fred Brown, A Compass and a Chart (Lillooet: Lived Experience Press), a new revised edition of which will be available next year. Andruss was Brown’s closest friend and among the last to leave the commune after Fred’s death. The biography documents Brown’s various experiments to build intentional communities in the American West. He didn’t live exclusively on the land. He taught in a remote B.C. community. Castro hired him to teach philosophy at Havana University. (His daughter Satya also tells this story in her memoir Fidel and me.) This experience helped him land a tenured position at Simon Fraser University and his pension provided a steady source of income for the Camelsfoot commune.

A Compass and a Chart is not a completely celebratory biography; Andruss narrates Brown’s financial problems, struggles with alcoholism, and marital difficulties. Read together, these two provide complementary perspectives on Brown’s influence on a younger generation. His longer history of attempts to build alternatives provides one answer to Plant’s query: “What went wrong?” A life committed to building intentional community often involved more than one experiment. These experiments were responses to changing socio-economic realities and diverse cultural and intellectual movements.

I’m a farm kid, so I confess that I’m a bit puzzled by the confusion about why so many 1970s back-to-the-land initiatives did not last, as well as cynical responses to these shattered dreams. I grew up watching news stories about farm foreclosures in the American mid-west, with speculation and worry that this trend would cross the border. My family’s farm in southern Ontario is still going strong; others did not make it, though. Even though back-to-the-landers envisioned an alternative world, the inability to make ends meet from the land, and adapting to combine self-sufficiency with other forms of employment, fits with a broader narrative and longer history of precarious rural economies.

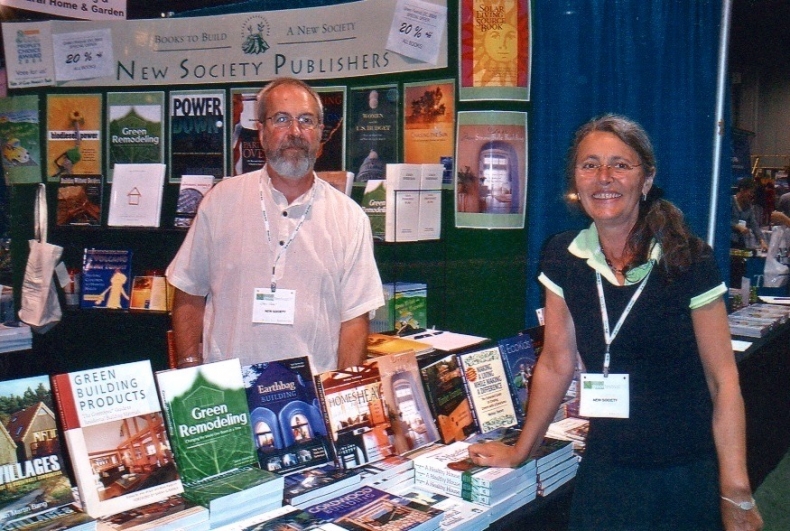

Yet it didn’t all go wrong. Plant – now director of New Society Publishers on Gabriola Island — explains that even though their commune split up, they have carried the values that brought them together in various projects in both urban and rural settings throughout their lives. Lessons learned in the Yalakom Valley informed later political projects, as Plant reflects:

At Camelsfoot, we found something precious and vital in ourselves, something that, unless nurtured to life, lies dormant in all of us like a frozen seed, a potential that sits waiting to germinate…. This knowing for me is the great legacy of Camelsfoot.

*

Nancy Janovicek teaches history at the University of Calgary. She is the author of No Place to Go: Local Histories of the Battered Women’s Shelter Movement (UBC Press, 2010) and co-editor of two collections on women’s and gender history. She’s currently writing a book on the back-to-the-land movement in the West Kootenays.

*

The Ormsby Review. More Books. More Reviews. More Often.

Reviews Editor: Richard Mackie

Reviews Publisher: Alan Twigg

The Ormsby Review is a journal service for serious coverage of B.C. books and authors, hosted by Simon Fraser University. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Robin Fisher, Cole Harris, Wade Davis, Hugh Johnston, Patricia Roy, David Stouck, and Graeme Wynn. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk.

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

New Society Publishing, circa 2011.

Leave a Reply