The quiet reckoning

Patrick Lane's final verses are about the life of the spirit, weary with the dust of the world. They are also an emotive farewell from a poet nearing eighty.

July 12th, 2022

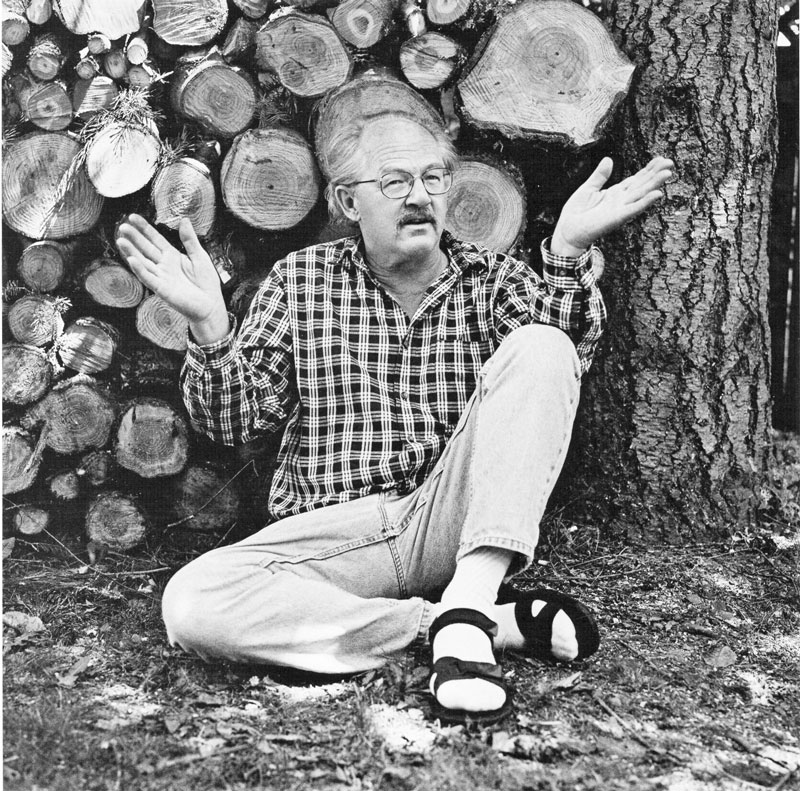

Patrick Lane at home, shortly before he died in 2019.

Reviewing The Quiet In Me: Poems by Patrick Lane, Trevor Carolan writes “This is the receding artist’s sayonara, when love is a happy hurt.”

Come to me from beyond the fields and streams,

the sweet lands, the places of fruit and blossom,

the song of the falling water and wild birds.

Let your heart be the sound of the wind seething…

-From the poem ‘Bitter’ by Patrick Lane

The Quiet In Me: Poems by Patrick Lane (Harbour $18.95)

Review by Trevor Carolan

Patrick Lane for a long time was emblematic among Canadian poets who brought exceptional technical proficiency and an intuitive Pacific Slope vernacular to their verse. Like Phyllis Webb and Robert Bringhurst, he conveyed a signature to the vivid air that poets breathe and work with here, charging it with street-sense and compassion, and sharing it abundantly. Lane moved further onward, tackling the novel and non-fiction, and it’s not too great a stretch to say that by the end of his life in 2019 he’d become a well-loved Canadian writer. That’s perhaps notable given his early knockabout years in the BC Interior where fighting your way through life was no mere figure of speech, or his literary service during the Sixties and Seventies when pugnacious interludes and drinking were part of the terrain.

Patrick Lane and Lorna Crozier.

Hugely well-travelled, Lane was a poet who needed settling down. He lucked out in partnering with prairie poet Lorna Crozier during his last forty years. She edits and introduces this final volume of Lane’s original work. Teaching at the University of Victoria and living nearby was a fructifying association for both. CanLit is not short of successful couples, but this marriage worked existentially and creatively, echoing the teamwork of Ray Carver and Tess Gallagher across nearby Juan de Fuca Strait in Port Angeles, Washington. These were fusions that succeeded, as the Romantic poet Percy Bysshe Shelley says, in producing poets and poems that contend with their time and grammars, with the distinctions of place and the eternal in producing work “convertible with respect to the highest [forms of] poetry.” That’s what we find in The Quiet In Me, a brilliant, emotive farewell from a poet nearing eighty.

Crozier’s introduction observes that Lane was “a poet who sang the darkness.” Straight off, in “Living In A Phantom Hut” that resonates with the haiku influence of Japanese poet, Basho (1644 – 1694), as ink-brush in hand, Lane reflects upon a long life on the road. But this is Canada and what we see is a “tuft of hair hooked on a strand of barbed wire/a rusted fence above the Barrière River, white water/old volcanoes, a crow picking at caribou bones.” That’s the North Thompson country he knew well, so majestically rugged it can break your heart. Thinking on a life and what might have been, or that can’t be undone, it’s all familiar to him now: “There is nowhere I can go that I haven’t been/When I hold the brush to my ear I hear the moon.” These are foreshadowing lines the like of China’s Tang Dynasty masters or the hurtin’ songs of Hank Snow the Singing Ranger.

Brief meditations on tiny hummingbirds— “who can find such a small heart?’ or on the “honey lands you will leave” remind one of the Irish proverb that there are things we can search for that cannot be sought, as well as those that one finds that cannot be looked for. We’re verging on the mystic, but it’s the route Lane posits for us in defining his laments for a natural world he sees in inevitable retreat: “Let your heart be the sound of the wind seething / …Listen to the wind in the discarded flutes of the bones.”

Brief meditations on tiny hummingbirds— “who can find such a small heart?’ or on the “honey lands you will leave” remind one of the Irish proverb that there are things we can search for that cannot be sought, as well as those that one finds that cannot be looked for. We’re verging on the mystic, but it’s the route Lane posits for us in defining his laments for a natural world he sees in inevitable retreat: “Let your heart be the sound of the wind seething / …Listen to the wind in the discarded flutes of the bones.”

Mystics aren’t immune: they ache too— “my body a museum for what’s gone,” (‘Bitter’)—and can get nostalgic for the hot cars, youth and passion in Chuck Berry’s tune ‘Maybellene,’ for just “doing the things you used to do.” If there’s levity, it comes with the cloak of humanity as in ‘Christmas Poem’ when Lane remembers his time as a small town first-aid man, dumbfounded in delivering a baby in the rawest situation, not sure if the result could also be a poem or “something/ about birth and death/something about stables and animals.” A northern mill town version of the biblical nativity, it brings a dose of suffering too, like old Zen master Hakuin’s teaching that the Holy Land is here before our very eyes.

Lane was once known as a love poet. In these mature poems it is the life of the spirit that emerges though, weary with the dust of the world. In ‘The Elder Tree’ he clears “dead branches the wind had carried/to where I come to pray.” What we see through his closed eyes is the regard of others; that he himself, and the elder tree, have become the oldest prayer. “We pray,” he says, “because we cannot look away.”

In ‘Kintsugi’, Lane weeps a little “without intent” in a series of deep-love, late-life recognitions where “there is only a little left to know.” Scarred, but honouring small blessings where “water returns to water,” there’s the gratitude and relief of an aging soul confronting its own evanescent mortality. This is the receding artist’s sayonara, when love is a happy hurt.

The bittersweet astringency of these Cascadian lyrics, with the long line used in the title poem in its thankful paying back and view of the end, shapes a suite of last honest words for those who’ve given to Lane through the years, for us. Rich in memorable lines, like Basho’s Narrow Road it’s a quiet reckoning. 978-1-55017-98-1

Patrick Lane, expounding by his woodpile. Photo Barry Peterson.

Leave a Reply