The malleable truth

In the Trump era, Orwell’s insights resonate profoundly.

January 18th, 2018

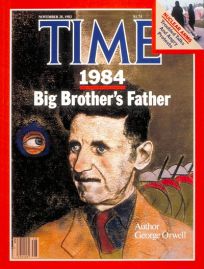

Victoria's Stephen Wadhams has interviewed seventy people who knew George Orwell (above).

Stephen Wadhams’ The Orwell Tapes is a collection of memories from those who crossed paths with the complex character who first described Big Brother, thoughtcrime, Newspeak and doublethink.

The Orwell Tapes

Vancouver: Locarno Press

by Stephen Wadhams

$18.50 / 9780995994614

*

George Orwell’s 1984 – or Nineteen Eighty-Four (original title)—rocketed to the top of the Amazon bestseller list in the U.S. last year immediately after Republican spin doctor Kellyanne Conway was asked on Meet the Press to explain why President Trump’s beleaguered press secretary, Sean Spicer, deliberately lied by saying Trump had attracted the “largest audience ever to witness an inauguration.”

The White House press secretary, explained Ms. Conway, “gave alternative facts.”

Now a B.C. book, The Orwell Tapes (Vancouver: Locarno Press $18.50), affords fascinating glimpses into the character of the 20th century’s most prophetic novelist, George Orwell, the man who predicted such dangerous nonsense.

In 1983, CBC’s Stephen Wadhams rented a car and drove for 5,000 kilometres in England, Scotland and Spain to interview 70 people who had known George Orwell from his birth in 1903 to his death in 1950.

The highlight was visiting the drafty room on the Scottish island of Jura where Orwell had written his classic work, 1984, while in failing health.

“This was where I felt sure I’d come as close to Orwell as it was possible to be,” recalls Wadhams, now retired in Victoria.

“I wanted to hear his clacking typewriter, smell his cigarette smoke which must have wafted all through the house. And above all, I wanted to be a fly on the wall observing him writing and re-writing his masterpiece.”

Wadham’s 50 hours of interviews gathered in 1983 resulted in two CBC Radio documentaries, George Orwell, A Radio Biography (1984) and The Orwell Tapes (2016). These, in turn, have resulted in the first release from a new B.C. imprint that is spearheaded by Scott Steedman, a respected editor, and Dimiter Savoff, who, as publisher of Simply Read Books, has garnered a controversial reputation for his treatment of authors.

The introduction is by Orwell’s friend, George Woodcock, the prodigious Vancouver anarchist who wrote an award-winning Orwell biography, The Crystal Spirit and Orwell’s Message: 1984 and the Present (Harbour 1984). There is also an updated preface by Wadhams and a newly-added foreword by Orwell scholar Peter Davison.

George Woodcock (left) with Mulk Raj Anand, George Orwell, William Empson, Herbert Read and Edmund Blunden, 1942

“We have always needed George Orwell,” writes Wadhams, “but now we need him more than ever, as the idea of truth itself is undermined by “fake news,” “alternative facts,” a declining respect for a rule of law based on facts and evidence, and the polarization of political discourse stoked by politicians promising simple solutions to complex problems.”

978-0995994614.

BOOK REVIEW

by Beverly Cramp

First there was Newspeak, now there’s fake news.

Big Brother has morphed into social media as data mining companies like Cambridge Analytica and Palantir Technologies brag about the thousands of data points they have on every adult in the United States.

Such previously unimaginable concepts were first brought to the world’s attention seventy years ago in the last book George Orwell wrote, Nineteen Eighty-Four (London: Secker & Warburg 1949). In Nineteen Eighty-Four, protagonist Winston Smith lives amid omnipresent government propaganda and surveillance in Airstrip One (formerly Great Britain), part of perpetually war-mongering Oceania. Torturers try to make him believe two and two does not equal four.

“Orwell knew very well where the manipulation of truth and the malignant distortion of language can lead,” writes Stephen Wadhams, gatherer of The Orwell Tapes (Locarno $18.50). “He’d seen it for himself in the Spanish Civil War and even done it himself as a BBC producer in wartime London, matching German propaganda with lies of his own, discovering the seductive power of being freed from normal constraints of truth telling.”

“Orwell knew very well where the manipulation of truth and the malignant distortion of language can lead,” writes Stephen Wadhams, gatherer of The Orwell Tapes (Locarno $18.50). “He’d seen it for himself in the Spanish Civil War and even done it himself as a BBC producer in wartime London, matching German propaganda with lies of his own, discovering the seductive power of being freed from normal constraints of truth telling.”

Joseph Goebbels, Hitler’s propaganda minister, had said “The secret of propaganda is repetition,” and Hitler, in his 1925 book, Mein Kampf, had already identified the propaganda technique of the Big Lie—a lie so extreme that no one would believe that someone “could have the impudence to distort the truth so infamously.”

It was George Orwell who revealed to a global audience how easy it is to manipulate people, how fragile our individuality can be, and how complete control of media and other technology can give rise to totalitarianism.

Now Stephen Wadhams’ interviews for The Orwell Tapes provide a unique prism for understanding the 20th century’s most prophetic voice of caution.

*

Eric Arthur Blair (pen name George Orwell) was born in 1903 in Motihari, then part of Bengal, but now called Bihar, which is in India. At the time, opium was legal and a big money-producer for the British Empire. Orwell’s father, Richard Blair, was an opium agent in the Indian Civil Service. Orwell’s mother was the much-younger Ida Blair, the half-French daughter of a tea merchant from Burma.

With parents from the lower rungs of the British Raj elite, Orwell joked he was, “born into what you might describe as the lower-upper-middle class.”

Eric Blair’s family and a rigidly conformist society conspired to shape him in a particular way.

“His parents certainly wanted him to conform,” writes Wadhams. “They made considerable financial sacrifices to send him to ‘good’ schools where he would meet the right people. But from the beginning he appears to have tried to break out of the mould. The consensus among his childhood friends and schoolmates is that the young Eric Blair was always strangely on the outside, observing but rarely joining in – and then usually to challenge and find fault. The picture given is that of an abrasive, free-thinking individual, but intelligent fault-finding is a far cry from open revolt; the young Blair was not a radical.”

That may explain why Orwell would study hard to eventually finish his education at Eton, one of the top boarding schools in Britain, and upon graduation spent five years in the colonial police force in Burma. It was expected of him. But the five years he spent in Burma deeply changed the young man.

“The inequities and oppression he saw there had a lasting effect on him,” says Wadhams. “In his writing he describes these years as traumatic. The ‘dirty end of Empire’ left him with an ‘enormous weight of guilt,’ which he felt he could expunge only by understanding and identifying with the oppressed classes of his own country.”

Thereafter, the young Eric Blair shifted his social climbing from up to down the ladder. But even though Orwell took up the underclasses as his adult cause, he retained many of the very English ways that he learned at British boarding schools.

At St. Cyprian’s, Orwell’s first boarding school, he became known for bookish ways. A fellow student there remembers, “He was round-faced, with straight hair, not in the least the bearded, long-faced number he turned out to be. I don’t think he was any good at sports. Blair and my brother both got bullied. I can remember very well the whole school booing and chasing them and getting them up against the wall of the gymnasium, with a view to bashing at them. I can’t think what anyone would have had against Blair. He was quite harmless. I think he was a born bookworm and would have liked to have been left in peace to pursue his own line of studies.”

Wadhams editorializes that Orwell probably didn’t suffer more than any other English boy, “uprooted from hearth and home and planted in the tough, regimented society of an English prep school. His early letters home offer glimpses of a boy coming to terms fairly cheerfully with his new environment.”

Orwell’s scholastic ability was noticed and he became one of the few “scholarship boys” that won free entry to the more reputable Wellington and later Eton School.

On holidays back at home, Orwell developed a lifelong love of the English countryside and fishing, rather conservative passions one doesn’t associate with a radical thinker. He also became attracted to Jacintha Buddicom, a girl two years’ older than him. Buddicom revealed that books were a common denominator between the two and that Blair dreamed of being a famous writer.

“I was never without a book in my hand and nor was he,” she said. “He was always going to write, and he was always going to be a Famous Writer. He used to say, ‘When I’m a famous…’ and I used to say, ‘When you’re a famous writer…’ That was his trademark, Eric the Famous Writer.”

Buddicom inspired the young Orwell to write a poem about her independent spirit. By then, he had already published a poem in a local newspaper at the age of 11, a patriotic ditty called “Awake! Young Men of England.”

From 1917 – 1922, Orwell was a King’s Scholar at Eton. A fellow Etonion recalls that Eric Blair loved arguing: “Endless arguments about all sorts of things, in which he was one of the great leaders. He was one of those boys who thought for himself, and at an age when a good many schoolboys haven’t graduated out of thinking the way they’d been taught to think.”

Upon graduation from Eton, Blair chose not to continue onto Oxford or Cambridge. He hadn’t studied hard enough to win a scholarship and his parents couldn’t afford to send him. In those days, the usual career path was chosen based on who your father knew. In Blair’s case, it was the Indian Civil Service in Burma. And that was how Blair came to leave England for a job with the Burmese Police on October 27, 1922.

We see what Orwell discovered in the five following years in one of his early novels, Burmese Days. The fictional character, John Flory is angered by the sham of Imperial Britain and how it has made him, “a creature of the despotism, tied tighter than a monk or a savage by an unbreakable system of taboos.”

After Orwell’s first trip back home to England in 1927, he chose not to return to Burma, telling his family that he wanted to be a writer instead. It caused a small scandal according to longtime residents of the seaside town of Southwold where Orwell’s parents eventually retired.

“…he had socialist ideas I suppose, hadn’t he? And Mr. Blair Senior wouldn’t really agree with that. Also, I think there was a bit of a row when he gave up his job. I mean, young men didn’t give up jobs in those days. They did what their fathers wanted them to, more or less.”

Another resident remembered, “…Eric used to go on long walks across the marshes, looking for birds and flowers. He was very keen on that. And he was always talking to whoever he was with; it was usually only one person. He had his opinions which nobody really took any notice of till just before he died. Sad, wasn’t it? His first books were no use. When Down and Out was published as George Orwell, everybody here knew it was Eric. We were all rather horrified at it – his being a tramp, you know. We thought it was rather a funny thing to do. I think his parents thought so too.”

Even the local tailor agreed that Orwell was unusual, saying “He was looked upon here as a little bit eccentric,” later adding that Orwell’s father was a snob and that if the tailor, who was not considered ‘society’, encountered the elder Blair on a Sunday, the old autocrat would walk straight past him with no gesture of recognition.

“Avril [Orwell’s younger sister] was a bit the same. It was a bit of an honour to be served cakes by her! They’d all got a bit of that. I didn’t notice it with Eric so much, though.”

Shortly after Orwell returned from Burma, he was asked to define his own politics. He replied, “Tory anarchist.” Wadhams notes here that although Orwell later embraced socialism in the 1930s, “he never lost his suspicion of organizations and institutions.”

Wadhams describes Orwell’s socialism as not being so much about changing human society based on some doctrine. “Orwell’s socialism sprang from a simple, passionate desire to support the underdog, to right obvious wrongs. If the role of the underdog shifted from the worker to the boss, Orwell was more than likely to switch sides. This made him a contradictory character without the apparent consistency of orthodox reformers who were more willing to adhere to theories long after the supporting facts had changed.”

Wadhams contends it was Orwell’s hatred of injustice that led him to write about poverty. “And with a straightforward and powerful subject came his equally straightforward and powerful writing style,” writes Wadhams.

Orwell started “tramping” in East London in the autumn, 1927 followed by a stint in Paris the following spring. That may account for his first professional article being published in Le Monde in 1928.

Although slumming it provided the material for another early book, Down and Out in London and Paris, it likely strained his health says Wadhams. “Orwell always felt that he had to write from experience…and was constantly stimulating his imagination by going out into the world to find ‘experiences.’ And in doing so – as investigator, journalist, and novelist – Orwell always got his hands dirty. If he was going to write about tramps, he would live with tramps. If he was to document the poverty of the depressed mining communities of the north of England, he would live among the unemployed and go down into the mines himself. There is no doubt that Orwell damaged his health by ‘slumming it’ in London and Paris and trudging around Wigan, Barnsley and Liverpool in February and March 1936.”

Although slumming it provided the material for another early book, Down and Out in London and Paris, it likely strained his health says Wadhams. “Orwell always felt that he had to write from experience…and was constantly stimulating his imagination by going out into the world to find ‘experiences.’ And in doing so – as investigator, journalist, and novelist – Orwell always got his hands dirty. If he was going to write about tramps, he would live with tramps. If he was to document the poverty of the depressed mining communities of the north of England, he would live among the unemployed and go down into the mines himself. There is no doubt that Orwell damaged his health by ‘slumming it’ in London and Paris and trudging around Wigan, Barnsley and Liverpool in February and March 1936.”

In February 1929, Orwell spent several weeks in Paris’s Hôpital Cochin with pneumonia. Then, before Christmas in 1933, he came down with pneumonia again. Clearly, he had weak lungs. In 1938, Orwell suffered a tubercular lesion in one lung and entered a sanitorium in Kent – a harbinger of what his last years would be like.

Before Orwell’s’ father died, he saw his son’s first published book. A friend, Mabel Fierz helped Orwell find the publisher Victor Gollancz.

Orwell bared his heart to Fierz. “That was a great sorrow to him, that he never came up to his father’s expectations. His father didn’t think he’d ever make money as a writer, and when his father was dying [1939] they were able to show him Orwell’s latest book, and that was a great comfort to Eric. So, his father and he parted friends when his father died. That was the reason he changed his name – that if his book was an absolute failure, he didn’t want the name Blair, his father’s name, to be thought badly of.”

Fierz also sheds light on Orwell’s early romantic life. “He used to say the one thing he wished in this world was that he’d been attractive to women. He liked women and had many girlfriends, I think, in Burma. He had a girl in Southwold and another girl in London. He was rather a womanizer, yet he was afraid he wasn’t attractive.”

It was through Fierz that Orwell met his first wife Eileen O’Shaughnessy in 1935. She had graduated in English from Oxford University. Her friend Lydia Jackson recalled the meeting.

“A fellow student of ours gave a party. George and Richard Rees were there, and I remember looking at the two of them. They were both standing by the fireplace, leaning on it, and I thought what unattractive men they were. Rather faded and worn. That was my impression. Anyway, after that party in London she told me that Eric Blair ‘sort of’ proposed to her, saying that he wasn’t much good, but even so perhaps she would consider him. And I said, ‘And did you?’ and she said yes. I was rather appalled…But Eileen had said before, that when she reached thirty she would get married. George talked in a way that intrigued her, interested her, because he was an unusual person. I’m very doubtful if she was in love with him. I think it must have been his outspokenness that attracted her.”

The next year Orwell moved to a small cottage in Wallington, Hertfordshire where he married Eileen. In the rented cottage, Orwell divided his time between writing The Road to Wigan Pier and acting as the village shopkeeper. He hoped to earn a small income and “some independence from the ups and downs of life as a moderately successful author,” writes Wadhams.

In any event, less than a year later, in January 1937, Orwell went to Spain to fight for the Spanish Republican Government as it was under attack by General Franco. Eileen followed, arriving in Barcelona in February, visiting Orwell at the front for two days in the middle of March.

“Fighting with a group of mainly British volunteers who, like him, had gone to Spain to combat fascism and prevent the wider war many believed was otherwise inevitable, Orwell felt at one with the working class,” says Wadhams. “He was noting what he saw, and his observations would no doubt end up in print, but he was also fighting shoulder to shoulder with British working men, and for a working-class cause: an elected government that sought to challenge the traditional Spanish elite.”

Two events from this time period might catch the casual Orwell reader by surprise. The first, and one that is well-known to Orwell scholars and historians is that although Orwell was initially inspired by the revolutionary atmosphere in Barcelona, by the time he left six months later with a throat wound (he had been shot through the throat while fighting), the atmosphere had turned poisonous. Turns out that among the socialist militias who came to the Republican Government’s aid, there were Trotskyists. As a result, the communists who controlled the Spanish Republicans began persecuting Orwell’s militia.

“Orwell claimed he was in danger of being arrested, imprisoned or even shot by the communists, working men who had earlier been his comrades,” says Wadhams. Orwell himself wrote, “It was a queer business. We started off by being heroic defenders of democracy, and ended up by slipping over the border with the police at our heels.”

Orwell was shocked to see his fellow workers spending more time and energy fighting each other than their common enemy. He also believed that the Soviet Union had become an anti-revolutionary force, helping to suppress many of the socialists fighting in Spain. For these reasons, Orwell no longer supported the Soviet Union. He wrote this into his account of the Spanish experience in Homage to Catalonia. The book thereafter put Orwell at odds with many other communists and socialists in England.

The second happening recalled by one of Orwell’s fellow fighters, was that Orwell diligently fought when he had to and likely killed people on the Fascist side. “We were attacking a troublesome salient, and Orwell wanted a hand grenade and I gave him one,” says Douglas Moyle who was in Orwell’s contingent. “He threw it, and there was a scream from a person being wounded, or perhaps even being killed by it.”

The second happening recalled by one of Orwell’s fellow fighters, was that Orwell diligently fought when he had to and likely killed people on the Fascist side. “We were attacking a troublesome salient, and Orwell wanted a hand grenade and I gave him one,” says Douglas Moyle who was in Orwell’s contingent. “He threw it, and there was a scream from a person being wounded, or perhaps even being killed by it.”

But as Moyle adds, the military action was rare and he often found Orwell reading to pass time in the trenches. “I was surprised to find him sitting quietly by himself, sheltering from the cold wind, reading a little volume of Shakespeare’s plays. He didn’t speak, and I realized he would rather be left alone. We thought he was rather ‘putting it on,’ but as a literary man he was doing no more than taking some exercise in the sort of thing he liked doing.”

The youngest soldier in Orwell’s group, 18-year-old Stafford Cottman says Orwell was a natural leader. “He had the common touch. He could talk to anyone,” recalls Cottman. “You had respect for him. He knew what he was talking about, you felt he did. There are people who one is more inclined to listen to than others, and George Orwell was such a man.”

Orwell returned to his Wallington cottage in England with Eileen where he wrote Homage. His fellow Spanish fighters often visited him, including Moyle who notes that Eileen cooked a lovely dinner with all the trimmings. Afterwards Moyle and Orwell went on long walks in the countryside, taking Orwell’s dog along. “He was a lovely French poodle, and he was called Marx.”

After spending time in a Kent sanatorium for a tubercular lesion, Orwell and Eileen travelled to Morocco in the winter of 1938 for Orwell’s health. Here, Orwell wrote the novel Coming Up for Air that warned of war and included themes he would fully explore in his tour de force, Nineteen Eight Four.

When the second world war started, Eileen moved to London to work in the Censorship Department. Orwell was to follow in August 1941, taking a job at BBC Radio as a producer in the Indian Service. They kept the Wallington cottage for weekends.

Just prior to the BBC job, Orwell wrote and published a short book, that called for an English revolution. While at the home of this book’s future publisher, Frederic Warburg, Orwell met Tosco Fyvel. “He was tall, gaunt, with deep grooves in his face. Poor hair, poor skin, and a poor little mustache. He looked like a sort of seedy sahib, one of the many British Imperial administrators I’d met in the Middle East,” says Fyvel of his first impression of Orwell. “At the time we all believed you could have both patriotism and socialism. Orwell was trying to identify himself with England in its finest hour. Out of this meeting came the project for Searchlight Books. I insisted Orwell should write the first one. It was called The Lion and the Unicorn. In it Orwell wrote as a patriotic socialist. He hoped for a British revolution, but it had to be a patriotic revolution. So my credit was, I managed to extract from Orwell, with this book, the only really positive, optimistic book he ever wrote.”

Whether or not Fyvel can take all the credit for what he described as Orwell’s “moment of hope” is up for conjecture. But he quotes Orwell as supporting the upper-class Etonians who could be counted on to fight for their country. “He always said that the British ruling classes might be politically and financially corrupt, but they were not morally corrupt…I mean when the hour came, they were all ready to fight and give their lives for the country.”

Orwell was refused war service due to his bad health. To contribute, he became a sergeant for the Home Guard. His publisher Warburg was in the same St. John’s Wood company. He recalled, that, “there was practically nothing about the Home Guard that didn’t suit Orwell’s temperament, until it began to be efficient.”

Henry Swanzy joined the BBC at the same time as Orwell. The two became friends and Orwell invited Swanzy to his and Eileen’s London flat for tea. “I always remember the extraordinary remark he made about her before I met her. He said, ‘Well, come along to tea on Sunday, my wife isn’t a bad old stick.’ Don’t you think that was a very odd expression? Of course that is a phrase that was used very much in middle-class circles, really, and I did notice in Orwell a kind of arrogance, or superiority towards materialism and the whole money society, the sort of attitude where it wasn’t altogether done to make a lot of money, where to be Left was an anti-materialistic thing.”

In addition to his radio work, Orwell freelanced articles for Horizon, Partisan Review, Tribune, The Observer and other publications. He resigned from the BBC in 1943 to work on a new book. He met a young translator of Ibsen and Strindberg named Michael Meyer who thought it would be a good idea to arrange a meeting between Orwell and the novelist Graham Greene. The three met in a Soho restaurant on a hot June day. Meyer worried that it might not go well because Greene thought George was a good writer, but not a good novelist. And Orwell thought any religion, which was so important to Greene, was more or less humbug.

“I felt very small, because I’m only five foot eight, and Graham Greene is six foot two and Orwell was six foot four. But they liked each other at once and got on very well. They were both very straight, unaffected men. They hated any kind of affectation, they were both very independent thinkers, and so appealed to each other.”

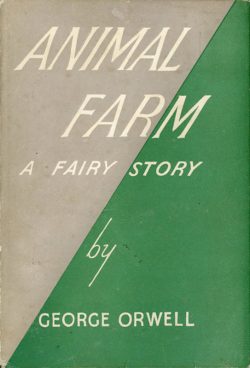

Meyer found that Orwell wasn’t good at describing the plots of his books although he floated his story ideas and theories to his many friends and fellow writers. “I once asked George what he was doing, and he said, ‘I’m writing a kind of parable, about people who are blind to the dangers of totalitarianism.’ He described the new book as being about a farm run by people, where the animals take over and make just as bad a job of it so they call in the humans again. And that was Animal Farm…It’s so marvelously simple, one of the wisest and deepest books ever written. When I read it, I was staggered and delighted because it bore no relation to his awful summary.”

Orwell and his wife adopted a baby boy, Richard, before Animal Farm was published. Tragically, Eileen died shortly afterwards while under anesthetic for an operation. Orwell hired a housekeeper to look after himself and Richard. It could have been a difficult time because many publishers had shied away from Animal Farm. The problem being, writes Wadhams the book’s “clear anti-Soviet theme made publishers nervous; Stalin was still a vital ally of the British Government.”

When the Book-of-the-Month Club in the United States chose Animal Farm in 1946 and gave it an initial printing of half a million copies, Orwell finally had financial security for the first time in his life.

Fellow writer and friend Malcom Muggeridge saw Animal Farm as a masterpiece satire although he understood the reluctance of publishers at the time. “It’s a beautiful piece of work, and it was refused by fourteen publishers (twelve in the USA), so that’s a good sign! I asked Gollancz [Victor] once how he felt about turning down Animal Farm, and he said, ‘Well, I regret it as a publisher, but I don’t regret it as a citizen, because at that time it was right not to have something which was an obvious attack on the USSR.’ Even that wasn’t quite true, you know, because although it was the USSR that people had in mind, at the same time I think that George was really making a case against every form of authoritarian government, and it just happened that the model available at that time was the USSR. What obsessed George in writing Animal Farm was that human beings were going to lose their taste for freedom. And I think that was a just fear. This is what he dreaded.”

If Orwell was now financially free to devote his time to writing, he was also a very sick man writes Wadhams. “From the moment Orwell began writing Nineteen Eighty-Four in the summer of 1946, he knew there was a danger that the ill health that had shadowed him all his life might prevent him from committing to paper the ideas he had been formulating for several years.”

Orwell spent time living in a stone farmhouse that summer in the northern part of Jura, an underpopulated island in the Inner Hebrides on the Scottish west coast. “There in his stuffy upstairs bedroom, with his hand-rolled cigarette dangling from his lips, he worked on the manuscript of Nineteen Eighty-Four, looking up occasionally to watch the ocean waves crashing on the shore a few yards away,” writes Wadhams.

Orwell was driven to warn the English and the wider Western world of what he claimed in a letter as, “perversions to which a centralized economy is liable and which have already been partly realized in Communism and Fascism.” Orwell added that he believed, “totalitarian ideas have taken root in the minds of intellectuals everywhere and I have tried to draw these ideas out to their logical consequences.”

Orwell’s working title for the book was “The Last Man in Europe,” because that was how he saw himself says Wadhams, “a solitary man fighting against the powerful forces of an advancing machine society, a mass society that would drain from the individual the taste for freedom.”

Yet when Orwell published Nineteen Eighty-Four, he found himself having to explain what he meant, says Wadhams. “The book was, to his dismay, instantly adopted by the right wing in the United States, to be used as ammunition against the Soviet Union and as anti-socialist propaganda generally. But Orwell was against totalitarianism of the left or the right. For him, Big Brother might be in the Pentagon or the Kremlin, thought control remained thought control whether the technique was torture or the television set, and during the Cold War his fears about the degradation and distortion of language would be borne out on both sides of the Iron Curtain, whether the subject was the ‘pacification’ of Vietnam villages or the ‘liquidation’ of Soviet dissidents.”

Yet when Orwell published Nineteen Eighty-Four, he found himself having to explain what he meant, says Wadhams. “The book was, to his dismay, instantly adopted by the right wing in the United States, to be used as ammunition against the Soviet Union and as anti-socialist propaganda generally. But Orwell was against totalitarianism of the left or the right. For him, Big Brother might be in the Pentagon or the Kremlin, thought control remained thought control whether the technique was torture or the television set, and during the Cold War his fears about the degradation and distortion of language would be borne out on both sides of the Iron Curtain, whether the subject was the ‘pacification’ of Vietnam villages or the ‘liquidation’ of Soviet dissidents.”

The beauty Jura held for Orwell was in stark contrast to the dark, pessimistic and ugly world of Nineteen Eighty-Four’s main character, Winston Smith. To take a break, Orwell “would go downstairs and perhaps take his young son Richard lobster fishing or, if he felt strong enough, walk over the moorland to visit his nearest neighbours, a mile and a half away,” writes Wadhams. “A fisherman on Jura described him as ‘a true communist – by which I mean a true communalist.’ In an old-fashioned setting of independent-minded but interdependent farmers and fishermen, Orwell wrote of a world in which the old and sturdy values he cherished had given way to cold, modern tyranny.”

In 1948, when Orwell finished the second draft of Nineteen Eighty-Four and sent it to his publisher on December 4, he was seriously ill. The next month he moved to a Sanitorium in southern England. Nineteen Eighty-Four was published on June 8, 1949 and in July was the American Book of the Month Club selection.

Orwell moved to his final “home”, the University College Hospital in London on September 3. The next month, he convinced Sonia Brownell, an editorial assistant for Horizon, to marry him. His first wife had died in 1945. Author Stephen Spender, a longtime friend of Orwell’s believes Brownell married the dying man for good reasons although it was to affect her for the rest of her life.

“I think [Orwell] was very much in love with Sonia and had been for some time. She was fond of him, and she was in a position to make him happy. She also knew that he was going to die. Therefore it seemed a rational proposition. But decisions arrived at on that sort of rational basis never turn out how you think they will, and when he died Sonia felt intensely unhappy. She blamed herself and thought she had done the wrong thing, and so took over the cause of George Orwell for the rest of her life, and she never really recovered from this. You see, I think Sonia always wanted to have a genius in her life. She had a romantic conception of genius. Orwell, to some extent, fitted her idea of the solitary genius who needed backing. She was always in search of her genius.”

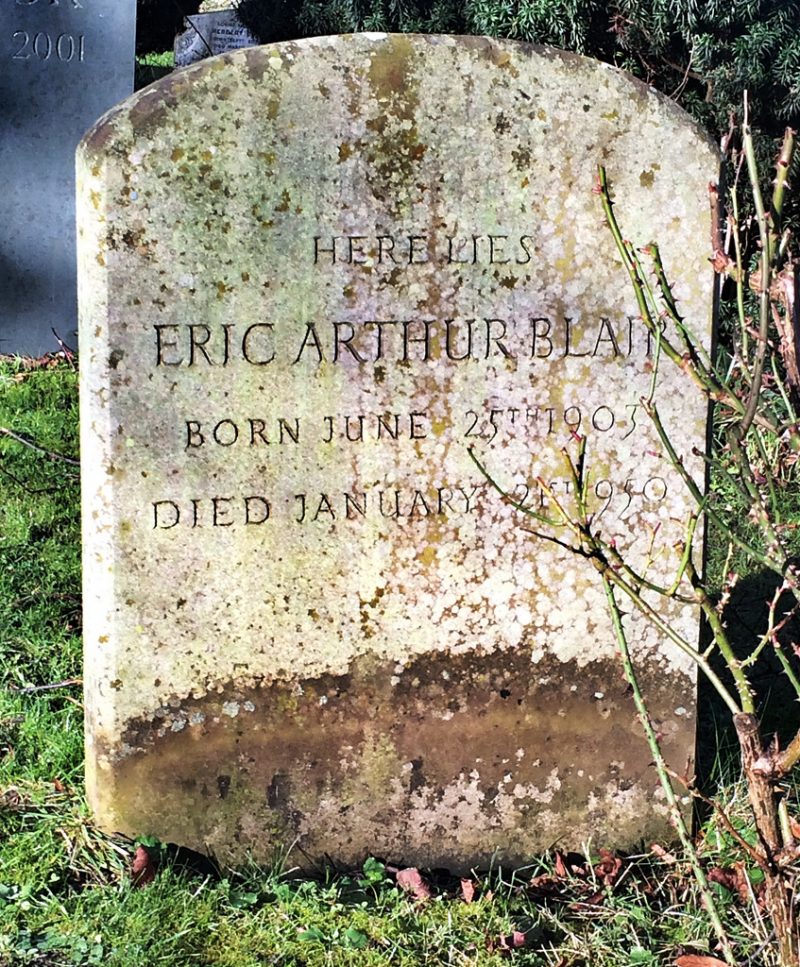

Orwell died in the evening of January 21, 1950, alone in his hospital room. Five days later he was buried in the churchyard of All Saints, Sutton Courtenay – a wish that Orwell had requested in his will. A funeral service was held despite Orwell being a lapsed Anglican.

The reverend Gordon Dunstan who led the service describes Orwell’s resting place: “His grave here has just an old English rose on it, which he asked for. He asked in fact that it might be left untrimmed, untended, but you know how roses grow, and they become straggly and a nuisance. Well, this is his grave. And it says, quite simply – again, I believe at his own request – ‘Here lies Eric Arthur Blair, born June 25th, 1903, died January 21st, 1950.’”

ABOUT STEPHEN WADHAMS:

Born in Weymouth, England, in 1945, Stephen Wadhams joined the BBC in 1968. He spent 18 months as a volunteer broadcaster in Malawi, Africa, before moving to Canada in 1974 to join the CBC Radio program “As it Happens.” He then spent ten years as a documentary producer for “Sunday Morning,” producing many high-profile projects in Canada, the US, Europe and Africa. From 1990 to his retirement in 2016, Wadhams created radio documentaries for the CBC, helping colleagues and more than 200 members of the public tell their stories on the programs “Outfront” and “Living out Loud.”

Born in Weymouth, England, in 1945, Stephen Wadhams joined the BBC in 1968. He spent 18 months as a volunteer broadcaster in Malawi, Africa, before moving to Canada in 1974 to join the CBC Radio program “As it Happens.” He then spent ten years as a documentary producer for “Sunday Morning,” producing many high-profile projects in Canada, the US, Europe and Africa. From 1990 to his retirement in 2016, Wadhams created radio documentaries for the CBC, helping colleagues and more than 200 members of the public tell their stories on the programs “Outfront” and “Living out Loud.”

*

Born and raised in Valemount, B.C., Beverly Cramp has degrees from Simon Fraser University (B.A.) and the University of Calgary (MBA). A respected freelance journalist who has written about architecture and art for decades, she first co-wrote Vancouver Book of Everything (MacIntyre Purcell Publishing $14.95) with Samantha Amara. Beverly Cramp’s second book, Pacific National Exhibition: 100 Years of Fun (Echo Genesis 2010), won a silver prize from the Independent Publisher Book Awards in 2011 in the Canada-West, Best Regional Non-Fiction category. Her forthcoming third book is a history of Dayton Boots, a company that makes handcrafted boots and shoes in Vancouver. An associate editor of B.C. BookWorld, she previously edited a newspaper for the Musqueam Indian Band for three years, and served as Executive Director of the BC Book Prizes in the 1990s. She also manages a business that guides people through the process of publishing books, most commonly memoirs.

*

The Ormsby Review. More Readers. More Reviews. More Often.

Reviews Editor: Richard Mackie

Reviews Publisher: Alan Twigg — BC BookWorld / ABCBookWorld / BCBookLook / BC BookAwards / The Literary Map of B.C. / The Ormsby Review

The Ormsby Review is a new journal for serious coverage of B.C. literature and other arts. It is hosted by Simon Fraser University. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Robin Fisher, Cole Harris, Wade Davis, Hugh Johnston, Patricia Roy, David Stouck, and Graeme Wynn.

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

Leave a Reply