Spiritualism in the pews

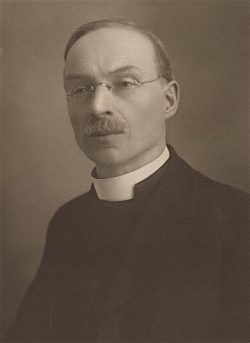

Globetrotting Anglican Missionary Frederick Du Vernet (1860-1924) was the Archbishop of the Diocese of Caledonia. He died in Prince Rupert in 1924.

May 14th, 2019

Pamela Klassen recalls a "spiritual pioneer" who came to B.C. in 1904. Photo by Johnny Guatto

The title of Pamela Klassen’s The Story of Radio Mind refers to unorthodox telepathy experiments conducted by Du Vernet.

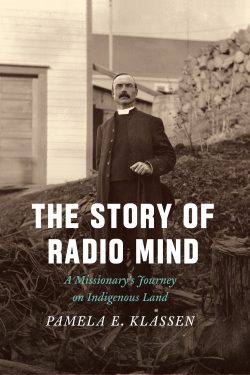

The Story of Radio Mind: A Missionary’s Journey on Indigenous Land

by Pamela Klassen

London and Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 2018

$27.50 (U.S.) / 9780226552736

Reviewed by Susan Neylan

*

Colonialism has spiritual dimensions; the process of creating a country like Canada transcends physical space and expands into metaphysical realms to permeate the very stories we tell about the spirits of these lands. With her new book, Professor of Religion at the University of Toronto, Pamela Klassen, takes readers on an exploration of what she calls the “spiritual invention of Canada,” all extrapolated through the profile of one man, Frederick Du Vernet (1860-1924).

Colonialism has spiritual dimensions; the process of creating a country like Canada transcends physical space and expands into metaphysical realms to permeate the very stories we tell about the spirits of these lands. With her new book, Professor of Religion at the University of Toronto, Pamela Klassen, takes readers on an exploration of what she calls the “spiritual invention of Canada,” all extrapolated through the profile of one man, Frederick Du Vernet (1860-1924).

This journey considers the colonialism of Indigenous peoples, the role of the Anglican Church of Canada in state building, and even the belief in psychic communication. The radio mind of the book’s title refers to telepathy experiments Du Vernet conducted and publicized late in his career, a rather unorthodox interest for the then Anglican Archbishop of Caledonia and Metropolitan of the Ecclesiastical Province of British Columbia.

But it was this kind of unconventionality that first drew Klassen to this historical figure. “I had found a mystic of mediation at the highest echelons of the Anglican Church,” she writes. “Combining his excitement over the innovations of radio technology with what psychology was newly revealing about the complexity of human consciousness, Du Vernet saw himself as opening up a new spiritual frequency for us all” (p. 183)

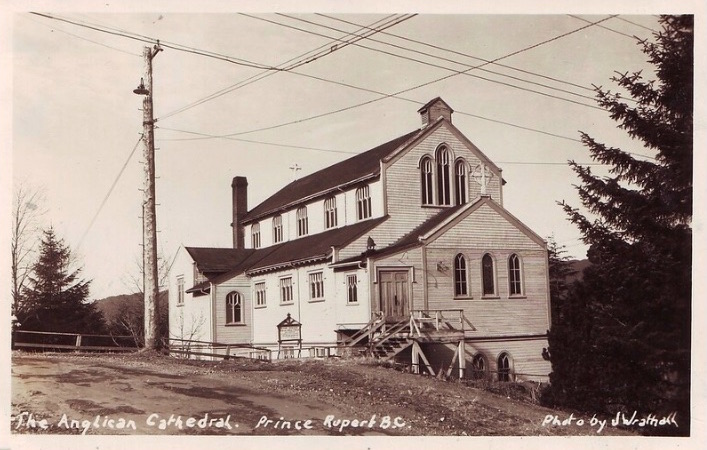

Sir Alfred Smithers of the Grand Trunk Pacific Railway and Bishop Du Vernet at Prince Rupert, circa 1912. Photo courtesy of Library and Archives Canada.

In many ways, The Story of Radio Mind defies simplistic categorization — it is part biography of Du Vernet; part series of case studies of various media (print culture, photography, map-making, and radio broadcast) and their role in the colonialism of Indigenous peoples; and part scholarly reflection. Klassen herself is an actor in the narrative, frequently ruminating about research, the paths of Indigenous-Settler reconciliation underway in this country, and what an individual like Du Vernet can tell us about these processes. Klassen regards Du Vernet with empathy without being apologetic, and by shifting the vantage to point to a single participant, shows us how we can better understand the complexities and contradictions of settler colonialism in this country.

Frederick Du Vernet was a missionary, Anglican minister and later archbishop and metropolitan whose career spanned the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. This was a transformative time for the church he served, informed by internal tensions between low and high Anglicanism and influenced by a movement towards Protestant unity at the national level while its work among Indigenous peoples contended with the withdrawal of global missionary enterprises in the international context. Throughout his life, Du Vernet adopted a conciliatory approach. He was educated at the evangelical Wycliffe College and soon became active in the mission work of the college and that of the Canadian Church Missionary Society. He was always an avid writer and contributed to religious journals, serving at various times as editor of leading Anglican publications. Du Vernet held posts in Montreal and Toronto before moving in 1904 to British Columbia to take up the post of Bishop of Caledonia. He lived in Prince Rupert until his death in 1924.

CPR coastal steamers at Prince Rupert, circa 1912. McRae brothers photo, courtesy of The Wayfarers’ Bookshop

Rather than describing the simple chronology of Du Vernet’s life, Klassen presents him primarily through a series of case studies intended to unpack spiritual reformulations that were taking place. Readers will find that some of these case studies are more successful than others. For instance, in her fourth chapter Klassen examines Du Vernet’s 1898 visit to Manidoo Ziibi (Rainy River) in Treaty 3 territory in Ontario. As with many of his Protestant contemporaries, Du Vernet utilized photography as a tool of mission work, snapping people, church buildings, and graveyards as a record of his travels and as proof of progress in Christianization in this Anishinaabe community. Du Vernet’s photo-taking was the vector by which he saw Indigenous peoples on the one hand, as an “other” in need of salvation, while on the other hand, viewed them as loving parents and upright Christians.

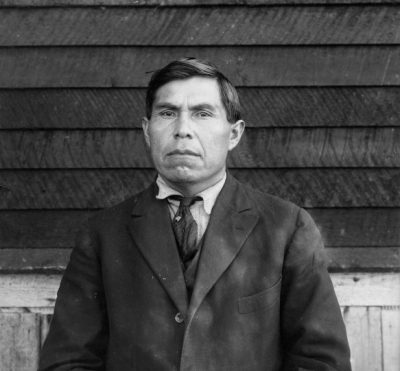

Frederick Herbert Du Vernet. Photo courtesy the Archives of the Diocese of New Westminster and the Ecclesiastical Province of British Columbia & Yukon

Yet Klassen analyzes this visioning entirely from Du Vernet’s diary descriptions and not his visual representations. Indeed, none of Du Vernet’s photographs appear to have survived, and the ones she reproduces here (seemingly to convey content — they are portraits of the Cree Anglican missionary, Jermiah Johnston, and his family who had welcomed Du Vernet into the community) were taken at a later date, in another context and place. Klassen rationalizes her position: “Photographs were really not all that important after all; it was the photographic event — whether resisted or accommodated — that counted” (p. 77).

Even so, scholarship on missionary uses of photography is well developed. Yes, a single primary source might provide some insights, but the absence of the physical execution of his photographic activity — the pictures themselves — strikes me as an odd choice for her to have made the central focus for an entire chapter. A far more inclusive understanding of Du Vernet’s time in this Anishinaabe community is found in Klassen’s subsequent collaborative work with the Rainy River First Nations and the Kay-Nah-Chi-Wah-Nung Historical Centre, who recently have integrated Du Vernet’s 1898 diary entries into a digital exhibit. The website “Kiinawin Kawindomowin — Story Nations” can be found here: http://storynations.utoronto.ca/storynations_wp/

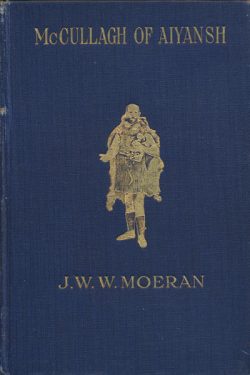

In contrast, Klassen’s study of the power of text when created locally through printing presses offers a much more compelling case. Chapter six “follows Frederick Du Vernet in his relationship with one of his longest-serving missionary colleagues, the Irishman James Benjamin McCullagh, as they grappled with the promises and unexpected properties of print” (p. 129). McCullagh called the printing press his “iron pulpit.” The first press arrived on the Nass River in 1898 and was used to publicize, fundraise, and celebrate successful Anglican mission work. At the same time, “its power to make stories mobile and proliferating” equally served the Nisga’a themselves in their battle to preserve their rights to land and sovereignty (p. 129). After all, writes Klassen, “[t]he printing press was not a spiritual medium with one voice” (p. 133). In this chapter she does a masterful job at exposing inconsistency and oftentimes incoherence in church responses to the Indigenous rights movement and gives her readers glimpses of an Indigenizing Christianity under development along the Nass River.

Lastly, The Story of Radio Mind is a scholarly musing about the spiritual dimensions of colonialism Klassen encountered in archives, on the land, and in the people she met as she physically retraced Du Vernet’s steps from Toronto to Manidoo Ziibi and Prince Rupert. She writes of encounters with archival documents as “gifts,” describes the delight with which she engaged with the marginalia she found in the books of Du Vernet’s personal library, and ponders the enduring Indigenous presence that lies behind the streets of her home neighbourhood in Toronto. The tone she was able to strike throughout makes the book approachable and surely will resonate with non-specialist audiences.

For Klassen, one of the most pressing questions concerned the nature of the Indigenous influence on Du Vernet’s experiments with spiritual energies. She writes with certainty that “…Du Vernet’s journey to radio mind was the conversion of the missionary himself, from missionary-bishop to episcopal shaman” (p. 233). However, in the end, the precise connection between radio mind and Indigenous spiritual connections and practices remains elusive. That Du Vernet was affected by Indigenous peoples is not in question, and Klassen does a good job of revealing the mutually respectful relationships he had cultivated over his lifetime with specific individuals, beginning with his teacher, the first Inuk priest, Simon Gibbons (who would also become kin when he married Du Vernet’s sister), his admiration for the Johnston family at Manidoo Ziibi, to finally his rapport with Nisga’a and Haida leaders from the north coast, such as Paul Mercer and Alfred Adams.

Klassen demonstrates moments of alliance where, in his capacity as Archbishop of the Diocese of Caledonia, Du Vernet listened and responded to Indigenous concerns. Du Vernet frequently wrote his superiors and published critically about the lack of resolution to Indigenous land claims or the recognition of Indigenous property. And while firmly entrenched in the administration of a church complacent in the cultural genocide of Indigenous peoples, Du Vernet denounced the violence of residential schools, criticized the assault it wrought on the bonds of family and community, and was disturbed over the unhealthy effects residential schools imposed on the children’s minds and bodies.

Scholars often appreciate the colonial project in Canada in terms of large processes — the imperialism, assimilation, and genocide perpetrated against Indigneous peoples, lands, and cultures; in individuals, such as Du Vernet, Klassen shows us an embodiment of contradiction within these processes. Despite genuinely supportive and sympathetic associations with Indigenous peoples, “Du Vernet was a spiritual pioneer in many senses,” she writes, “including as a mystic of mediation and as a settler who claimed Indigenous land” (p. 191).

Du Vernet’s radio mind has much in common with today’s path to Indigenous-Settler reconciliation. It held out promise as an inclusive and soul-expanding frequency at best, but at its worst, reproduced more colonial static, and facilitated the Settler replacement narratives of these lands.

*

Susan Neylan is an Associate Professor of History at Wilfrid Laurier University in Waterloo, Ontario. She is an expert on the history of Canada with a particular interest in Indigenous-non-Indigenous relations and the Indigenous-Christian encounter on the Northwest Coast of North America in the 19th and 20th centuries. Author of “The Heavens are Changing:” Nineteenth-Century Protestant Missions and Tsimshian Christianity” (McGill-Queen’s University Press 2003), and co-editor of New Histories for Old: Changing Perspectives on Canada’s Aboriginal Pasts (UBC Press, 2007). Neylan has also been published in the Canadian Journal of History, History Compass, and Journal of Religion, among others. Recently her research interests have turned to social histories focused on expressions of culture that may have been first introduced by missionaries that have since taken on a distinctive life of their own as meaningful expressions of Indigenous identities — marching bands and sports such as basketball. She is working on a book covering a range of topics related to the 20th-century Indigenous-church relationship, with special emphasis on developments among Protestant forms of Christianity in British Columbia.

*

The Ormsby Review. More Books. More Reviews. More Often.

Editor/Designer/Writer: Richard Mackie

Publisher/Writer: Alan Twigg

The Ormsby Review is a journal service for serious coverage of B.C. books and authors, hosted by Simon Fraser University. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Robin Fisher, Cole Harris, Wade Davis, Hugh Johnston, Patricia Roy, David Stouck, and Graeme Wynn. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. As of September, 2018, Provincial Government Patron: Creative BC

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

Pamela Klassen with her University of Toronto researchers Sarina Annis and Amy Fisher in Prince Rupert, 2012.

Leave a Reply