She lifts us up where we belong

With a foreword by Joni Mitchell, the new Buffy Sainte-Marie biography is adulatory for lots of good reasons.

October 02nd, 2018

Buffy Sainte-Marie was born on Saskatchewan's Cree Piapot reserve, 1941. Photo by Matt Barnes.

Blacklisted by two American presidents, the Universal Soldier songstress breastfed her child on Sesame Street in 1977 and won a Best Song Oscar in 1983 for Up Where We Belong.

Buffy Sainte-Marie: The Authorized Biography

by Andrea Warner, foreword by Joni Mitchell

Vancouver: Greystone Books 2018

$36.00 / 9781771643580

Reviewed by Jo-Anne Fiske

*

Envision a young woman, naïve and conservative in 1965. She sat proudly in her undergraduate history class as the professor led discussion on the fifty-year commemoration of Canada’s contribution to the First World War, “the war to end all wars.” Canada’s efforts had brought the country to the world stage when its citizen army in the trenches of the Western Front emerged as shock troops dreaded by their enemy and respected by their allies. This young woman was particularly proud of the Canadian infantry for her late father had enlisted voluntarily. Because of his service she was now receiving Department of Veteran Affairs sponsorship to attend university.

Envision a young woman, naïve and conservative in 1965. She sat proudly in her undergraduate history class as the professor led discussion on the fifty-year commemoration of Canada’s contribution to the First World War, “the war to end all wars.” Canada’s efforts had brought the country to the world stage when its citizen army in the trenches of the Western Front emerged as shock troops dreaded by their enemy and respected by their allies. This young woman was particularly proud of the Canadian infantry for her late father had enlisted voluntarily. Because of his service she was now receiving Department of Veteran Affairs sponsorship to attend university.

Then contemplate how this same young woman felt as a classmate rose to register his condemnation of all war, reciting the now iconic lines from “The Universal Soldier:”

He’s the one who gives his body

As a weapon of the war

And without him all this killing can’t go on

He’s the universal soldier and he really is to blame.

Thus was I introduced to the art and heart of Buffy Sainte-Marie: folk singer extraordinaire whose unflinching confrontation with injustice disrupted my complacency.

Written in 1962 and released in 1964, “Universal Soldier,” which condemned America’s war in Vietnam, became one of two protest anthems that defined Sainte-Marie’s musical and political agendas in the 1960s and 70s. On the same album, It’s My Way! , “Now that the Buffalo’s Gone” was equally compelling in its indictment of injustices perpetrated against Indigenous people; it called for Americans to recognize contemporary confiscation of Indigenous land specifically violation of treaty to build Kinzua Dam in Seneca territory: “Oh, it’s all in the past you can say / But it’s still going on here today.”

As with many of her protest folksongs, “Now that the Buffalo’s Gone” resonates today as First Nations continue their struggles to defend their lands, which leads Sainte-Marie to update her lyrics as new injustices are revealed.

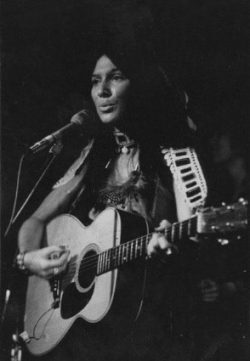

As the turbulence of the anti-war movement spread into the 1970s, and social justice demands rose and intertwined in the voices of Black American, Native American, and women, Buffy Sainte-Marie stood at the centre of artistic leadership of the era. She had surfaced as a guitarist and folk singer from the urban coffee shop scene she had shared with the likes of Woody Guthrie and Peter Seeger and then forged ahead of them as she merged a range of genres — funk, soul rock, torch ballads, and love songs, and innovative vocal techniques drawn from pow-wow music and the vibrato of Edith Piaf with new electronic technologies. She wrote music scores for movies and joined the cast of “Sesame Street” — and famously breastfed her baby on television in 1977.

The heady successes of the 1970s were followed by earning an Oscar in 1983 for the melody “Up Where We Belong,” for the movie An Officer and a Gentleman, co-written by her then husband Jack Nitzsche. The marriage, however, soon became abusive, and after seven years Sainte-Marie fled with her young son, Cody Wolfchild. Sainte Marie reflects on the abuse and its personal costs and warns women who remain with abusive partners that “It was not worth it. Please do not go through it.” Warner posits the abusive relationship that ended in 1989 as one reason for a sixteen-year break between recording her 1976 album Sweet America and her 1992 comeback album Coincidence and Likely Stories, which Warner praises for its political provocation and sonic experimentation.

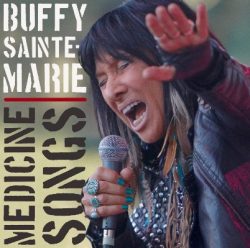

A long hiatus in recording had ended. Albums were released in 1996 and 1998, with the latter including new protest songs that won her a Juno for Best Indigenous Album. In 2015 she released Power in the Blood, which brought her international acclaim. Here she is as intensely political and vibrant as she was in 1964. She was awarded Junos and the Polaris Music Prize for Power in the Blood in 2015 and a Juno for her 2017 release Medicine Songs, a collection of her protest anthems that spans her five-decade career and amplifies her commitment to Indigenous resistance. It should surprise no one that her numerous awards include more than a dozen honorary degrees, induction into the Canadian Music Hall of Fame, and installation as Officer of the Order of Canada.

A long hiatus in recording had ended. Albums were released in 1996 and 1998, with the latter including new protest songs that won her a Juno for Best Indigenous Album. In 2015 she released Power in the Blood, which brought her international acclaim. Here she is as intensely political and vibrant as she was in 1964. She was awarded Junos and the Polaris Music Prize for Power in the Blood in 2015 and a Juno for her 2017 release Medicine Songs, a collection of her protest anthems that spans her five-decade career and amplifies her commitment to Indigenous resistance. It should surprise no one that her numerous awards include more than a dozen honorary degrees, induction into the Canadian Music Hall of Fame, and installation as Officer of the Order of Canada.

Ever the pathbreaker, Sainte-Marie has also earned accolades for her visual art, where once again she led in the digital world, being among the first to display large-scale digital painting in museums across North America.

Throughout her diverse achievements, Sainte-Marie has remained steadfast in her political conviction and has never flinched from challenging colonization. While Sainte-Marie is best known for her protest music and her eclectic performances, her advocacy for Indigenous peoples stretches far beyond the music world. She founded a charity, the Nihewan Foundation, to fund Indigenous post secondary students, and created digital Indigenized curricula, “The Cradleboard Project,” for elementary children.

Throughout her diverse achievements, Sainte-Marie has remained steadfast in her political conviction and has never flinched from challenging colonization. While Sainte-Marie is best known for her protest music and her eclectic performances, her advocacy for Indigenous peoples stretches far beyond the music world. She founded a charity, the Nihewan Foundation, to fund Indigenous post secondary students, and created digital Indigenized curricula, “The Cradleboard Project,” for elementary children.

As she was fifty years ago, she is today an activist and advocate for Indigenous rights. She has embraced the tenets of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission. Earlier this year she toured First Nations communities of Saskatchewan with members of the Regina Symphony Orchestra. She continues to innovate as she melds classical music with her own intense pow-wow-inspired electronic genres, paying tribute to Tchaikovsky, whose music first influenced her as a very young child.

In her authorized biography, musical journalist Andrea Warner traces the life journey and achievements of this remarkable Canadian-born Cree artist, illustrating how Sainte-Marie’s personal life and political principles informed her work. From her birth on the Cree Piapot reserve in Saskatchewan in 1941, to her adoption by Albert and Winnifred (of Mi’kmaq descent) Saint-Marie, who raised her in Maine and Massachusetts, through her studies in oriental philosophy and education, and to her home in Hawai’i with a herd of goats, Warner links personal experiences and reminiscences to motivations for particular lyrics and technological innovations in Sainte-Marie’s oeuvre.

Buffy Sainte-Marie at Idle No More Protest at Manitoba Legislature, January 2013. Photo by Phil Hossack

“The Universal Soldier,” she tells us, was inspired when — on a flight from Mexico to Toronto — Saint Marie met wounded American soldiers returning from Vietnam. “Cod’ine” not only speaks to her personal negative experience with opiates, but also stands as a critique of shifting music culture from coffee houses to bars, which she views as undermining the student culture that supported political change.

While she highlights Sainte-Marie’s artistic and technological achievements, Warner does not overlook her political activism and its repercussions. Warner addresses the blacklisting of Sainte-Marie by two American presidents, Johnson and Nixon, files held by the FBI, and her close ties with the American Indian Movement. Warner ponders the impact that political advocacy and Black listings had on Sainte-Marie’s career, notably in the 1980s when her popularity waned.

Warner organizes her book chronologically and thematically. Two chapters introduce Sainte-Marie and cover her childhood and youth. These are followed by another fifteen that cover the content and techniques of selected recordings and the contexts from which they take their meaning. “Interludes” are interspersed chapters that comprise excerpts from her interviews with Sainte-Marie. These provide glimpses of Sainte-Marie’s passions and personality based on advice she gives to young parents on how to survive and contest colonization. Through it all, Sainte-Marie’s creativity and optimism shine. As Warner brings the biography to a close, she quotes Sainte-Marie: “But I love the world and I love people, I really do…. After all, I’ve seen the almost impossible become possible in really big ways.”

Warner grounds her work in some sixty hours of interviews that took place face-to-face and over the phone and internet. Additionally, Warner joined Sainte-Marie on two tours, one on the east coast and one on the west. Warner turns to journalistic accounts and reviews of Sainte-Marie’s work from the past fifty years to supplement her interviews, to which she adds a scant number of short citations from Sainte-Marie’s colleagues and peers who are clearly her fans and admirers, whether they are from the realm of music or childhood friends.

As the genre of authorized biography implies, the book’s subject had a central role in its formation. In an Afterword, “Buffy and Me,” Warner glowingly describes her “lovely little friendship” with Buffy and acknowledges that “together we’ve made a book” (p. 277). “Buffy has combed every inch of this book, every page bears her fingerprints, and I can her voice at every turn” (p. 276).

This has led to weaknesses that are general to the genre: Warner praises, sympathizes, and empathizes with the life story Sainte-Marie has shared, but does not challenge her subject’s perspectives. Where Sainte-Marie is willing to dig deep into her experiences and emotional pain, Warner is willing to follow. Where Sainte-Marie is reticent, as she is in her relationships with members of the American Indian Movement, and two of her three marriages, Warner treads softly.

Similarly, Warner does not explore in detail any of the contentious relations Sainte-Marie had with the music industry, notably Vanguard Records, with whom she released her first works. What Warner does do is capture her spirit and energy. She never lets us forget that Sainte-Marie was and is at the forefront: ever an innovator. She allows Sainte-Marie’s voice to flow in unedited interview excerpts. Concisely and clearly, Warner reviews her selected tracks bringing to the page the musical compositions that thunder and whisper, circling back through fifty years to remind us all that the issues Sainte-Marie contested in the 1960s are the social and political challenges we face today.

While a few may be uncomfortable with Warner’s laudatory tone, Sainte-Marie’s fans, young and old, will credit Warner with placing her subject up where she belongs.

*

Jo-Anne Fiske earned her masters (1981) and doctorate (1989) in Anthropology from UBC, and taught in the Women’s Studies department at the University of Northern British Columbia until 2004, when she joined the Women & Gender Studies Department at the University of Lethbridge. Since the 1970s she has been working extensively with First Nations in central British Columbia. Her joint work has documented the traditional legal order of the Lake Babine Nation (with Betty Patrick), traditional community governance and membership of the Lake Babine Nation (with Evelyn George) and women’s health and well-being of Saik’uz First Nation women (with Geraldine Thomas Flurer). She is the author (with Betty Patrick) of Cis dideen kat — When the Plumes Rise: The Way of the Lake Babine Nation (UBC Press, 2000). She lives at Fraser Lake, B.C. Today, inspired by her relationship with her late father, she is working on a manuscript on WWI military hospitals.

*

The Ormsby Review. More Books. More Reviews. More Often.

Editor/Designer/Writer: Richard Mackie

Publisher/Writer: Alan Twigg

The Ormsby Review is a journal service for serious coverage of B.C. books and authors, hosted by Simon Fraser University. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Robin Fisher, Cole Harris, Wade Davis, Hugh Johnston, Patricia Roy, David Stouck, and Graeme Wynn. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. As of September, 2018, Provincial Government Patron: Creative BC

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

Leave a Reply