#77 Rubber chicken, pot shops, sexism

January 22nd, 2017

Nelson is known for its resilience and creativity--but the patriarchy still governs.

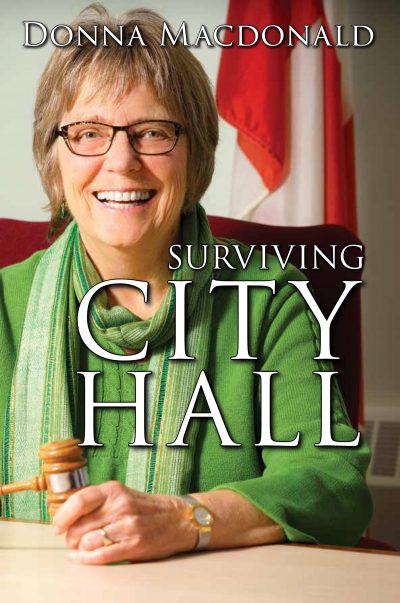

REVIEW: Surviving City Hall

By Donna Macdonald

Gibsons: Nightwood Editions, 2016.

$22.95 / 978-0-88971-320-8

Reviewed by Ginny Ratsoy

*

In Surviving City Hall, Donna Macdonald provides a memoir of her nineteen years as a city councillor in Nelson, B.C. and her attempt to run for mayor.

Reviewer Ginny Ratsoy reflects on this valuable account of political life for a woman in a smalltown.

*

The “Queen City” in the West Kootenay, Nelson, is often used as a model of adaptability because of its successful late-twentieth century transformation from a resource-based town to a tourism-based economy through its restoration of heritage buildings and focus on its artists. But, as Hillary Clinton’s recent attempt to take down Donald Trump clearly shows, many people still don’t trust a woman to hold the reins. Even Donna Macdonald’s mother didn’t approve of her daughter running for the top job as mayor of Nelson, despite her many years of service on city council.–Ed.

***

In 2010, the small city of Nelson, B.C., attracted the attention of The Guardian for weathering the most recent economic downturn — a feat the esteemed newspaper attributed partly to dollars from marijuana cultivation.

A similar hardiness is evident Nelson citizen Donna Macdonald. She survived almost two decades as a city councillor — weathering long hours, low pay, two unsuccessful bids for mayor, and the slings and arrows of fellow politicians and local citizens.

Part memoir, part informal handbook on municipal government and its relationship to its federal, provincial, and regional counterparts, and part portrait of a small city, Surviving City Hall is a lively, frank, jam-packed read that should attract diverse audiences.

As a memoir, the book traces Macdonald’s left-wing bent. This was nurtured during two years at UBC — which taught her that she “didn’t want to put band-aids on this old capitalist world;” instead she “wanted fundamental change” (p. 17) — and practised through her involvement in women’s, peace, workers’, and environmental movements.

Donna Macdonald believes people of Nelson can maintain a “vision of an informed and effective culture of participation.”

This progressivism informs her philosophies and actions throughout her career at Nelson’s City Hall and is an important connecting thread in what sometimes is a challenging book to follow.

An engagingly complex character emerges as Macdonald puts her idealism into practice. She comes across as both assertive and humble. She is outspoken and stands up for her beliefs tenaciously; yet at the same time she acknowledges self-doubt, frustration, and disappointment. Admirably honest, she reveals her warts.

For example, after devoting several chapters to her experiences of and responses to gender inequality in politics, she admits that, when Nelson elected its first female mayor in 2014 — subsequent to her own two unsuccessful attempts at the office and her departure from politics — she initially felt “heartbroken and a little jealous” (p. 134).

As a handbook, Surviving City Hall provides important insights into politics in lively first-hand accounts aided by reflection. Macdonald devotes an informative chapter to the rights and responsibilities of the three levels of government, using a classic children’s book metaphor. The feds are Papa Bear, the provincial level is Mama Bear, and, of course, the municipal level is Baby Bear.

Macdonald argues convincingly that local governments are unduly hamstrung by their limited options to generate revenue and by the section of the Community Charter that requires annual balanced budgets. A later chapter, examining the relationship between regional districts and the municipalities and taking issue with rural residents using, but not paying taxes for, city services, is similarly persuasive.

Surviving City Hall also describes “outside the box” political methodologies. After studying the referendum approach of former Rossland politician Andre Carrel and the deliberative democracy approach of Porto Alegre, Brazil, Macdonald spearheaded a citizens’ working group in Nelson. Although that initiative did not have the result she hoped for, her account could be useful to others contemplating fundamental civic change.

Surviving City Hall also describes “outside the box” political methodologies. After studying the referendum approach of former Rossland politician Andre Carrel and the deliberative democracy approach of Porto Alegre, Brazil, Macdonald spearheaded a citizens’ working group in Nelson. Although that initiative did not have the result she hoped for, her account could be useful to others contemplating fundamental civic change.

Perhaps Surviving City Hall’s foremost function as a handbook is to present an insider’s perspective on the daily life of a city councillor. Leadership roles in local politics are physically and emotionally demanding, regardless of the city’s size.

Macdonald recounts phone calls from irate locals at all hours, disputes with other politicians, the high price of alienating the business community, and “the opportunities to dine on overcooked chicken [that] are legion” (p. 51). Her detailed, candid, and witty anecdotes will be food for thought for aspiring politicians.

As a portrait of a city, Surviving City Hall doesn’t pull any punches, as indicated by the subheadings of a chapter on the mayors with whom she worked: “The People Pleaser,” “The Autocrat,” and “The Schmoozer.”

Macdonald is not afraid to name names and point fingers. For example, she wryly analyzes a council decision (after her tenure) to ignore widespread opposition and haphazardly transform the business licence fees structure, the most egregious result being a 1000 percent increase for the tiny Holy Smoke Culture Shop — in line with the fee for the big banks.

The result was a strange bedfellows scenario between conservative big business types and new agers, a cost of $15,000 to the city as it tried to collect unpaid fees, and a reversal a year later. There is something of Stephen Leacock’s Sunshine Sketches of a Little Town in Macdonald’s portrait of Nelson: her portrayal is witty, critical, and affectionate.

My only major criticism of Surviving City Hall is that the reader is sometimes overwhelmed not only by the wealth of both information and anecdote the book provides, but by the abrupt twists and turns within and between chapters. Although Macdonald and her editors are to be credited for helpful subheadings and chapter encapsulations, at times I found it challenging to follow threads and chronology.

My only major criticism of Surviving City Hall is that the reader is sometimes overwhelmed not only by the wealth of both information and anecdote the book provides, but by the abrupt twists and turns within and between chapters. Although Macdonald and her editors are to be credited for helpful subheadings and chapter encapsulations, at times I found it challenging to follow threads and chronology.

Overall, however, Surviving City Hall captures the essence of its author, local politics, and the city of Nelson. I recommend it to anyone interested in an insightful memoir, an overview of the practicalities of political life, and an engaging depiction of a resilient city.

Donna Macdonald has faith that the citizens of Nelson, nestled in its Selkirk Mountain valley replete with artists, pot shops, and issues small and large, have the potential to achieve a “vision of an informed and effective culture of participation” (p. 206).

Indeed, her choice of an epigraph by Vaclav Havel, Czechoslovakia’s last president – that “hope is a state of mind, not of the world” – indicates that Macdonald’s idealism, constantly tested, has prevailed.

*

Ginny Ratsoy is an Associate Professor of English at Thompson Rivers University specializing in Canadian literature. Recent courses have included British Columbian Literature and The Environment in Canadian Literature. Among her publications are Playing the Pacific Province (co-edited with James Hoffman) and Theatre in British Columbia. She has also co-edited (with W.F. Garrett-Petts and James Hoffman) Whose Culture Is It, Anyway? Community Engagement in Small Cities and published articles on theatre, playwrights, and small cities in British Columbia.

*

The Ormsby Review. More Readers. More Reviews. More Often.

Reviews Editor: Richard Mackie

Reviews Publisher: Alan Twigg

The Ormsby Review is hosted by Simon Fraser University Library.

—

BC BookWorld

ABCBookWorld

BCBookLook

BC BookAwards

The Literary Map of B.C.

The Ormsby Review

Leave a Reply