Off to the races indigenously

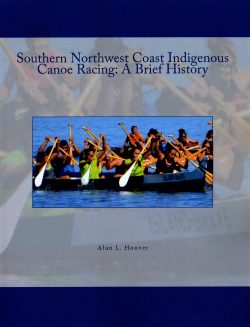

Alan Hoover has traced 200 wooden racing canoes for Southern Northwest Coast Indigenous Canoe Racing: A Brief History.

July 12th, 2018

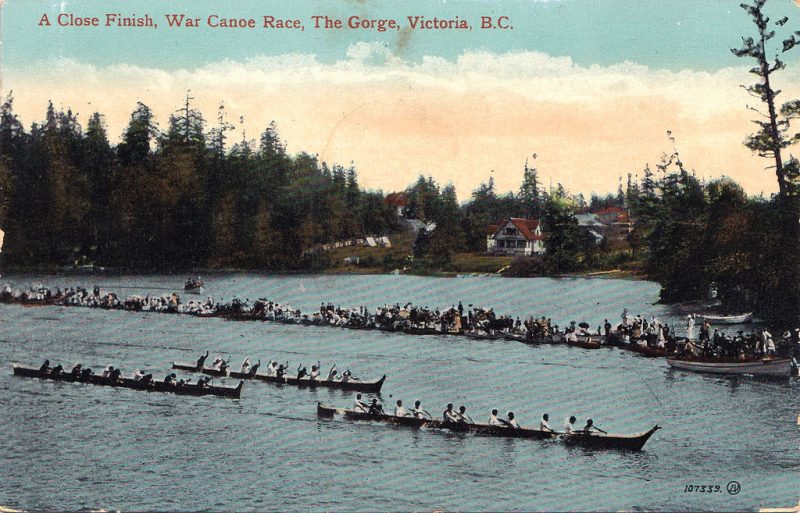

"Indians Racing In Front Of Government House. New Westminster, Queens Birthday,"1867

He documents the changes in paddle design and paddling styles as well as the serious physical and mental training by the racers.

Southern Northwest Coast Indigenous Canoe Racing: A Brief History

by Alan L. Hoover.

Victoria: Alan Hoover, 2018.

$14.95 / 9781775011903

Reviewed by Sanford Osler

Available at the Royal B.C. Museum Bookshop, Victoria

[Cover image: Painting by Jane Needham]

*

Once a year my local oceanfront park in North Vancouver fills with campers bringing dozens of long sleek wooden canoes to race over the weekend. This scene repeats itself throughout the summer on both sides of the Salish Sea and across the international border as the Coast Salish people continue their long tradition of gathering to compete in their beautiful racing canoes.

Once a year my local oceanfront park in North Vancouver fills with campers bringing dozens of long sleek wooden canoes to race over the weekend. This scene repeats itself throughout the summer on both sides of the Salish Sea and across the international border as the Coast Salish people continue their long tradition of gathering to compete in their beautiful racing canoes.

If you want to learn more about these craft and races, you can read Alan Hoover’s Southern Northwest Coast Indigenous Canoe Racing: A Brief History. Hoover, who spent over thirty years working with Northwest Coast Indigenous peoples and their material culture at the Royal British Columbia Museum, delved into studies, reports, and websites, and interviewed many of the participants at recent racing events to create this short (37 pages) publication on the evolution of the sport. Hoover also includes a useful appendix listing over 200 of these wooden canoes, some of which can be seen in today’s races, with data on the owner, date made, and dates used.

Women’s canoe race, North Vancouver. May 1962. Stanley Triggs photo.

He traces the evolution of racing canoes (also known as “war canoes”) over the last 150 years from “working canoes” with up to twenty paddlers, to long, light, and sleek canoes up to fifty feet in length typically designed for eleven, six, two, or single paddlers (or “pullers”). He also shows the resistance to, and ultimate acceptance of, the evolution from using only “dugouts” carved from single western red cedar trees to those made from many strips of cedar, as well as the use, on both canoe types, of layers of clear fibreglass cloth for extra strength and waterproofing. Today, both the dugout and strip canoes compete in the same races.

Hoover outlines the current race rules and prizes, along with the different age, gender, and distance categories, including special ones such as the “tip-over” and “mop fight” (where a padded pole is used to knock over those standing in rival canoes), and he provides the names of the winners in some of these races.

He documents the changes in paddle design and paddling styles as well as the serious physical and mental training by the racers. In my own research on the subject, I was told that coaches discouraged sex during the months before and during race season, and that a bulge in birth of “canoe season” babies could be seen nine months after the races ended!

I was especially interested in the changing purpose of these races. Canoes traditionally played essential roles in the lives of Coast Salish people for practical as well as social, ceremonial, and spiritual reasons. Canoe races, both spontaneous and organized, were part of this tradition.

Hoover focuses on the “Indian canoe races” that were included in non-Indigenous celebrations or organized by settlers. One of the earliest documented races took place at New Westminster in May 1865 in celebration of the Queen’s Birthday. At the request of Frederick Seymour, the new Governor of the Colony of British Columbia, local Catholic priests invited all the First Nations. In response, 3,500 people arrived in hundreds of canoes, singing Catholic hymns and trailing banners reading “Religion, Temperance and Civilization” before the next day’s races.

Hoover doesn’t delve into why the Coast Salish people continued to participate in these settler-organized events into the post-colonial era, when the federal Indian Act of 1876 first applied to B.C. It may have resulted from their love of the sport and the appeal of the prizes offered. It may also have been a response to the restrictions imposed upon Indigenous people by the Indian Act in organizing their own celebrations or travelling freely to other communities.

In any case, the races have now generally shifted to being self-organized and, along with other canoeing events such as longer trips in ocean-going canoes, serve to keep Indigenous traditions and skills alive.

For anyone wanting to learn more about this Indigenous canoe racing centred on the Salish Sea, Alan Hoover’s Southern Northwest Coast Indigenous Canoe Racing provides a well documented and illustrated description of its evolution over the last 150 years.

*

Sanford Osler has an MA from the University of British Columbia and has held leadership positions with national NGOs, major utilities, and financial institutions. He moved from Toronto to North Vancouver with his wife and two children in 1992. He is active in the community and is the past Chair of the North Vancouver Museum and Archives Commission and a past Board member of the North Vancouver District Public Library. Sanford was introduced to the canoe as a youngster, an event that sparked a lifelong interest in the role of the canoe in Canadian history and in our modern-day lives. This fascination led him to write Canoe Crossings: Understanding the Craft that Helped Shape British Columbia (Heritage House, 2014), which traced the history of canoes and other paddled watercraft from their first appearance in B.C. to the present, and highlighted the length, width, and depth of the relationship British Columbians have had with these craft.

*

The Ormsby Review. More Books. More Reviews. More Often.

Reviews Editor: Richard Mackie

Reviews Publisher/Designer: Alan Twigg

The Ormsby Review is a journal service for serious coverage of B.C. books and authors, hosted by Simon Fraser University. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Robin Fisher, Cole Harris, Wade Davis, Hugh Johnston, Patricia Roy, David Stouck, and Graeme Wynn. Scholarly

Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. As of September, 2018, Provincial Government Patron: CreativeBC

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

Fibreglass ocean-going canoe of the Urban Youth Association at the Pulling Together Canoe Journey, July, 2017. Paul McGrath photo, North Shore News.

Leave a Reply