Not just salmon poems

Nicholas Bradley praises the “fundamentally local character of the poetry” of Daphne Marlatt and Fred Wah.

November 18th, 2018

Daphne Marlatt. Shazia Hafiz Ramji photo.

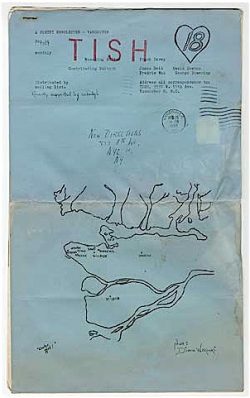

The collected early works of Wah (born 1939) and Marlatt (born 1942) reflect origins in the 1960s with Tish, the newsletter founded by the student-poets of UBC.

Intertidal: The Collected Earlier Poems, 1968–2008

by Daphne Marlatt, edited by Susan Holbrook

Vancouver: Talonbooks, 2017

$49.95 / 9781772011784

*

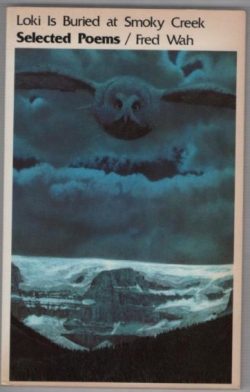

Scree: The Collected Earlier Poems, 1962–1991

by Fred Wah, edited by Jeff Derksen

Vancouver: Talonbooks, 2015

$49.95 / 9780889229471

Both books reviewed by Nicholas Bradley

*

T.S. Eliot might not have fared well in the Kootenays, Nicholas Bradley observes, but he would have understood that these B.C. poets were obliged to “[F]ind idioms that emerge from the places themselves. Eliot would have known that Loki is a trickster in Norse mythology, but not that Smoky Creek meets the Kootenay River at South Slocan, twenty kilometres downstream from Nelson.” — Ed.

*

Landslip and Delta: A Review by Nicholas Bradley.

When I was a nervous graduate student in search of a supervisor for my dissertation, I had to assure a sceptical professor that my proposed research would be suitably scholarly, and less flaky than it sounded. There we were in Ontario — in Toronto, no less — and I wanted to write about environmental poetry and the West Coast. “As long as there’s more to it than salmon poems,” my professor said, or words to that effect.

It was good advice. As an enthusiast of writing from British Columbia and the Pacific Northwest, I have a high tolerance for the geographically specific — for salmon poems, as it were — but those of us who are interested in local matters do well to remember that what seems obvious or important here is not always clear or pertinent to others there. The adjectives regional and local often have a pejorative connotation in the literary world, as if they were silently preceded by the adverb merely.

For decades, Daphne Marlatt and Fred Wah have been acclaimed as eminent Canadian authors — as figures of national significance — yet their bodies of work are intensely regional, almost perversely so. There are plenty of fish in Marlatt’s Intertidal (2017), and many mountains in Wah’s Scree (2015), and much else besides that indicates the fundamentally local character of the poetry. The books immerse readers in imaginative worlds formed by the poets’ syntheses of autobiography, local history, and environmental observation.

Reading them, I kept thinking how unlikely it is that these poems of Washout Creek, Canal Flats, and Finn Slough have travelled so far. And yet they have. Poems by Marlatt and Wah (and works in other genres) are widely anthologized, and routinely taught in university courses on Canadian literature. They have been the subject of numerous critical studies, as indicated by the useful bibliographies in Scree and Intertidal. Wah even served as Canada’s Parliamentary Poet Laureate (2011-13). To read Intertidal and Scree is therefore also to ponder how writers and their peculiar fascinations make their way in the world.

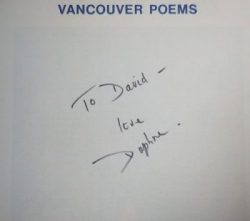

Marlatt’s best-known book of poetry is probably Steveston (1974), a quasi-ethnographic study of the eponymous town on the Fraser River, and of the fishers and cannery workers whose lives were bound to “Pacific Ocean flesh.” Elsewhere she writes intimately about Vancouver, about her life in the city, and about (and to) other writers whose lives have intersected hers. The coastal city’s importance is signalled most plainly in the title of Vancouver Poems (1972), but nearly all of her poems are, in a non-trivial sense, Vancouver poems. Her fiction, too, is local; Ana Historic (1988), for instance, is a Vancouver poem in prose.

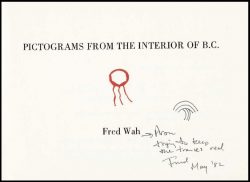

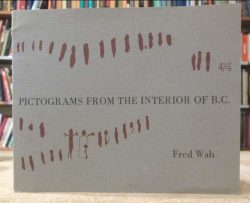

Wah’s poetry, meanwhile, catalogues the toponyms, landscapes, species, and characters of the province and especially of its inland terrain. Pictograms from the Interior of B.C. (1975) is a representative title, but So Far (1991) also suggests something essential about his writing, which is, as well as a chronicle of remote places, an ongoing record of his movements and perceptions. So Far — that is, until now. So Far — implying away, from here, so good.

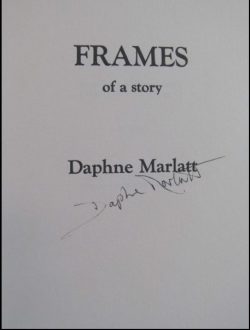

Marlatt and Wah have been publishing books of poetry since the 1960s. Intertidal and Scree, which collect the authors’ Earlier Poems, are mammoth, reputation-cementing volumes. The former is so weighty, in fact, that the cover came unglued as soon as I opened my copy. Intertidal spans Marlatt’s career, ranging from her uncollected poems of the 1960s and Frames of a Story (1968) to Between Brush Strokes (2008) and the uncollected poems of the 2000s. (“Earlier” is interpreted loosely.) Scree begins with poems published in the periodical Tish in the early 1960s and with the collection Lardeau (1965), and it concludes with the poems of So Far.

Issued by Talonbooks of Vancouver, Scree and Intertidal belong to the same series as Peacock Blue: The Collected Poems of Phyllis Webb (2014), an edition prepared by John Hulcoop, and Flow: New and Collected Poems (2018), by Roy Miki. The books reflect and reassert the stature of the authors concerned. And indeed the editors of Intertidal and Scree are certain of the poets’ achievement.

Editor Susan Holbrook writes, for instance, that Marlatt’s Rings (1971) changed her life: “I read Rings in my early twenties and remember a kind of ecstasy at encountering these unfamiliar and familiar rhythms and knowledges; almost two decades later, during my own day of giving birth, the text floated back into my consciousness to help me through, in both spiritual and practical ways.”

Jeff Derksen suggests that Wah’s poetry is a vital but disruptive part of Canadian literature: “Reading the works in Scree today gives a sense of the questions, coherences and fault lines within Canadian literature as well as the inevitable and powerful external influences, reconfigurations, and alignments that a cultural project springing out of a national imperative both encounter and counter.” These editions are works of tribute and consolidation.

The poets have been western Canadian writers since they were students at the University of British Columbia in the early 1960s, which is also where and when they were first associated with the Canadian avant-garde: for these poets, location, style, and literary tradition have always been linked. Marlatt was born in 1942 in Melbourne; her parents were British. Her first years were spent in Australia and then in Malaysia, one of the settings of her second novel, Taken (1996). Her family moved to Vancouver in 1951.

Wah was born in Swift Current, Saskatchewan, in 1939. His family moved to Trail, B.C., in 1943, and then to Nelson in 1948. The new place granted him a defining outlook. In 1976, he wrote that “I live in the ‘interior’ of British Columbia and such a qualification affects my particular sense of what the world looks like. We go ‘down’ to the coast, which is the exterior, the outside, the city.” When Marlatt began her studies at UBC in 1960, Wah was already there; the two students became part of a loose circle of ambitious young writers.

In the late 1950s and the very early 1960s — before the Beatles’ first LP, when F. R. Scott was arguing the Chatterley case — UBC was suffused at once by a lingering cultural conservatism and the spirit of change of the new decade. There was then no separate program in creative writing, but the Department of English supplied curious mentors in Earle Birney, a Canadian eminence, and Warren Tallman, an assistant professor from Seattle.

Birney belonged to the establishment that the students both courted and rejected, while Tallman helped introduce the budding authors of Point Grey to the exhilarating and often severely demanding poetry of Charles Olson, Robert Creeley, Robert Duncan, Jack Spicer, and other paragons of the New American Poetry.

Having read the American poets, and after having met Duncan himself, the students naturally created their own literary movement. With Frank Davey, George Bowering, Lionel Kearns, and others, Wah was responsible for Tish, the self-declared “poetry newsletter” that is remembered, despite or perhaps because of its brief existence, as one of the quintessential institutions of postmodern writing in this country. (Marlatt was first only peripherally involved, but she became an editor late in 1963.)

Tish attempted to make the experience of a specific place and time — the West Coast, now — the centre, or point of departure, of a new Canadian poetry. Tish was also, to be sure, a bid for recognition. Although its heyday lasted only from 1961 to 1963, it has long been part of the mythology of CanLit, its notoriety due in no small part to the nostalgic and even panegyrical recollections of its prime movers. As Gregory Betts has remarked, “the amount of reportage on the first period of Tish by outsiders pales in comparison to the amount of attention the principals have devoted to their inaugural literary effort. It was obviously felt to be deeply significant to their emergence as writers.”

In retrospect, it can be somewhat difficult to see how and why Tish was so radical and important. In Arrival: The Story of CanLit (2017), Nick Mount notes fairly that Tish was “a boys’ club, with boys’ jokes and mostly boys’ poems.” Marlatt’s poetry responds to this and other manifestations of power and authority, as she explains in Intertidal: “my writing was inevitably autobiographical and yet aware of my position as an innovative woman writer in a male-dominant world that included family, city, and trans-national culture.” Moreover, if Davey’s first book, D-Day and After (1962), was flawed by “the assumption that something becomes important simply by putting it in a poem,” as Mount maintains, so too were many of the poems in Tish.

Of more lasting importance than the actual issues of Tish was the Olsonian idea that geographical place and an exploratory, process-oriented poetics were closely allied. Intertidal and Scree are geographical terms used to suggest qualities emblematic of the poets’ oeuvres. Is Marlatt’s poetry as restless as the tide, and Wah’s stolid as stone? Maybe, but those who have trudged through it know that scree moves underfoot, making the hike uphill a Calvary and the way down an ankle-breaker. And beach-goers realize that the intertidal zone offers moments of calm when the tide is out and the hidden shore revealed. Such landscapes are mutable. As Holbrook understands it, the fluid metaphor connotes ecological attentiveness as well as poetic method:

Marlatt’s biocentric title … reflects the amplification of her longstanding passion and concern for the environment. It also resonates with her revisionary practice which, on both intra- and intertextual levels, enacts and extends the musical, the philosophical, the spiritual, and the political through turns and returns. Waves rush onshore and back, tides ease in and out, never flowing precisely the same way twice; these ocean rhythms, as anyone who has peered into a tide pool knows, create the dynamic liminal region where remarkable life thrives.

Derksen makes an analogous case for the word from geology:

As a title for this collection … scree is fitting because it is a deceptively simple word that wavers between the image of a mountainside and pure sound. Etymologically derived from the Old Norse term for “landslide” through to the Old English term for “glide,” scree is linked to movement and process. Wah’s poetry, particularly in the thirteen books gathered in this volume, is distinguished by its attention to the movement of language, the dynamism of poetic form, and a sense of place itself understood as a process of movement and stasis.

Here Derksen echoes Bowering, who wrote in his introduction to Wah’s Loki Is Buried at Smoky Creek (1980) that scree signals a point of origin, a central theme, and a way of writing:

If you have lived in the Interior you carry with you an image identified with that part of Canada: scree. Scree is the slope of rock debris at the bottom of a cliff. I didnt [sic] know the word (derived, again, from Old Norse), but when I was a kid I used to run down shale slides, a good test of quickness of whole-body, because you have to step before you know where your foot is going to light, or you will fall & be fallen upon. For years I told people about that stepping when I was trying to convey my sense of composing lyrics.

Fred Wah uses the word often, & even called his Castlegar poetry newsletter Scree. It makes a good concrete image for evidence that all things of the earth, even mountains, are always moving & changing. In sentimental paintings of wild grandeur one sees mountains & forests, but not scree. What causes scree is what the glacier causes; it is deconstruction, transcreation. It would be silly & homeless to try to shore up those fragments.

Bowering’s ironizing allusion to The Waste Land (“These fragments I have shored against my ruins”) seems to say that T. S. Eliot would not have fared well in the Kootenays, and that poets from these “part[s] of Canada” need not play Possum. They should instead find idioms that emerge from the places themselves. Eliot would have known that Loki is a trickster in Norse mythology, but not that Smoky Creek meets the Kootenay River at South Slocan, twenty kilometres downstream from Nelson. Wah, however, knew both worlds:

Loki is buried at Smoky Creek

He pointed at the water

he looked that way

towards the creek

then went there

through the fields to the west at night[.]

(from Breathin’ My Name with a Sigh, 1981)

In the years after Tish, Marlatt and Wah continued to write various forms of what is persistently termed “experimental poetry.” It is more accurate to describe such writing as a now well-established mode that eschews lyric conventions and presuppositions, including the conceit that a poem is a kind of perfected speech uttered by the introspective poet and overheard by the reader. Instead this poetry emphasizes the apparent inadequacy and instability of language itself, and the impossibility of conveying meaning directly or transparently. The poetic statement is therefore not a representation of reality, but rather an investigation of perception and language, the poetic mode not primarily declarative but interrogative.

Marlatt can still write of the musicality of language — “From Robert Duncan, and generally from projective verse, I inherited a notion of the poem as a musical score, that is, what is on the page with its spacing and indented lines is a kind of score for how to sound the poem aloud” — but poems in this vein adopt strategies that suggest the visual as well as the aural: “I use spacing between stanzas and stanzagraphs, even between words in a line sometimes, and I use punctuation, often idiosyncratically, in an attempt to sound, through tonal shifts, some of the wider mesh of perceptions and side-thoughts, the complex dance of memory and present phenomena that any sequence of moments will bring.”

For his part, Wah employs illustrations, makes unusual use of typography, and draws on many formal models, such that Scree includes the haibun of Waiting for Saskatchewan (1985) and the utaniki of So Far as well as lyrics, sequences, and long poems.

As a result of the poets’ formal and philosophical commitments, Intertidal and Scree do not depict B.C. in a conventionally representational fashion; Marlatt and Wah have not written the equivalent of what Bowering called “sentimental paintings.” At times in Scree, words defy explication: “unh unh nguh / w_______h / w_______h” (from Breathin’ My Name with a Sigh). Precedents exist for their versions of regionalism; a sustained analysis of the correspondences between Wah’s poetry and the works of Gary Snyder is long overdue, for instance. But these books also attest to the originality of the two poets, whose careers can be understood as extended attempts to come to terms with place, and in particular with places that are sites of social, political, and historical conflict — to become truly local in locations marked by injustices. Derksen suggests that Wah takes up aspects of Indigenous cultures in appropriate ways, as in Pictograms from the Interior of B.C.:

Read today, fortunately in a time when the cultural appropriation (and cultural dispossession) of Indigenous art and knowledge meets intense resistance, the poems in Pictograms … appear as an engagement with a place-based knowledge that is not rooted in the Western separation of first and second nature, nor reliant on the transformation of nature from use value to surplus value or profit (the metaphysics of capitalism). Wah’s poems do not try to force the rock paintings into a Western e by “reading” them as translatable texts (which would assume the smooth transfer of meaning from one knowledge form to another). Rather Wah uses this process of transcreation to test a relational sense of place that troubles the subject/object separation of Western philosophy in relation to Indigenous knowledges of land and place that the pictographs represent.

This assessment may be accurate, but its interpretative weight threatens to sink such simple poems as the following, which I present in its entirety: “ol’ moose inside ski-doo-type world / sliding down the milky way[.]” Or this poem, also from Pictograms:

On my way to get a pail of water

which way

down by the creek

down by the dark

and in the trees the night

buhdum, buhdum

bdum, bdum, bdum[.]

The wit in these poems is more evident when the text is accompanied by the pictograms (which are reproduced in Scree), but the contrast between the simplicity of Wah’s words and the complexity of Derksen’s analysis suggests a tension between the jazzy, playful nature of the poetry and the sometimes ponderous claims made on its behalf.

The wit in these poems is more evident when the text is accompanied by the pictograms (which are reproduced in Scree), but the contrast between the simplicity of Wah’s words and the complexity of Derksen’s analysis suggests a tension between the jazzy, playful nature of the poetry and the sometimes ponderous claims made on its behalf.

Intertidal and Scree are distinctive, eclectic, and remarkable editions. They are also each longer than six hundred pages, and in my view not all of the collected poems are equally exciting. Perhaps this reaction is inevitable; few poets produce enormous but consistently engaging bodies of work. Yet if an author’s importance is granted, as with Marlatt and Wah, then all of that writer’s works are intrinsically noteworthy to the critic, scholar, and bibliographer, if not necessarily to the lay reader; the famously turgid expanses of The Prelude will not be expunged from any Collected Wordsworth. And if poetry is a record of being in the world, if accounts of perception and experience are valued above the romantic image, the well-wrought urn, then capaciousness may be seen as a virtue.

Still, voluminous books demand patience, and readers of Scree and Intertidal may find some passages testing. Here is the beginning of Wah’s “What Does Qu’Appelle Mean” (from So Far):

Did you know I watered the Japanese cherry out front?

The Manchurian plum too.

How late did Jenefer sleep on Sunday?

I talked to my mom about using the wormy cherries for wine. Tell her about the worm in the tequila.

What did Erika do at Gray Creek?

I picked two cocoon-like burls off the apricot tree.

What do you think they are?

I think we should plant more flat or sugar peas from now on.

I cooked that halibut with some veggies and the leftover burnt brown rice.

And here is the opening of Marlatt’s Rings:

Like a stone. My what’s the matter? dropt as

mothering smothered by his snowy silence. Me?

the morning? or?

Metal clangs in zero weather cold hands

make. A jangling of rings, loose. Sky does not begin

today. Disguising offwhite of what the ground is. falling.

away from us.

… will look up, stare as if (Why do you make

so much noise? Slurping coffee he objects to. What if

it’s pleasure? Forgot. Noise occupies a room already

occupied by

Snow, as silence [….]

Such passages, typical enough, suggest that conscientious readers must be willing to dwell in these textual worlds for some time, learning the lingo and the lay of the land; readers in search of epigrams or epiphanies will be frustrated.

Those readers who find Wah’s observations unexpected and charming, and Marlatt’s questions and self-interruptions provocative, will discover that the poetry rewards the effort required to make sense of it. Those readers who find his thoughts banal, and her writing cryptic, will find Scree and Intertidal tough sledding. A middle ground is hard to envision.

But all readers will agree, I believe, that the books are impressive, carefully edited and attractively designed. They demand to be reckoned with, and my hope is that among their readers will be critics eager to perform the requisite tasks of reassessment and reinterpretation. I am grateful for the Collected Marlatt and the Collected Wah. Now I wait to be guided anew through this difficult country.

But all readers will agree, I believe, that the books are impressive, carefully edited and attractively designed. They demand to be reckoned with, and my hope is that among their readers will be critics eager to perform the requisite tasks of reassessment and reinterpretation. I am grateful for the Collected Marlatt and the Collected Wah. Now I wait to be guided anew through this difficult country.

*

Nicholas Bradley is an associate professor in the Department of English at the University of Victoria, where he teaches Canadian literature and American literature. His most recent book is Rain Shadow (University of Alberta Press, 2018), a collection of poems, several of which involve salmon.

*

Works Cited:

Betts, Gregory. “More of THIS/TISH/SHIT.” Rev. of When Tish Happens: The Unlikely Story of Canada’s “Most Influential Literary Magazine,” by Frank Davey. Canadian Poetry: Studies, Documents, Reviews 69 (Fall/Winter 2011): pp. 117–19.

Bowering, George. “The Poems of Fred Wah.” Loki Is Buried at Smoky Creek: Selected Poems. Edited by George Bowering. Vancouver: Talonbooks, 1980. pp. 9–22.

Mount, Nick. Arrival: The Story of CanLit. Toronto: Anansi, 2017.

Mount, Nick. Arrival: The Story of CanLit. Toronto: Anansi, 2017.

*

The Ormsby Review. More Books. More Reviews. More Often.

Editor/Designer/Writer: Richard Mackie

Publisher/Writer: Alan Twigg

The Ormsby Review is a journal service for serious coverage of B.C. books and authors, hosted by Simon Fraser University. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Robin Fisher, Cole Harris, Wade Davis, Hugh Johnston, Patricia Roy, David Stouck, and Graeme Wynn. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. As of September, 2018, Provincial Government Patron: Creative BC

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

Leave a Reply