#339 Missiles, murder & emasculation

July 09th, 2018

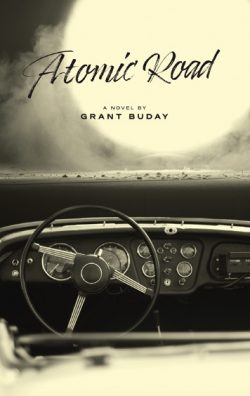

Atomic Road

by Grant Buday, with a foreword by John O’Brian

Vancouver: Anvil Press, 2018

$20 / 9781772141139

Reviewed by Dustin Cole

*

So it was all coming down,

So it was all coming down,

The future collapsing

like a rotten house. – from Atomic Road.

Recently I perused the Anvil Press website to see if a manuscript I had written might fit with the rest of their titles. Grant Buday’s new novel, Atomic Road, caught my eye. I have to admit I envied the concept, a sort of Cold War comedy-thriller starring art critic Clement Greenberg. “It’s probably about painting, too,” I thought. “Clever wag.” It turned out to be art historian John O’Brian’s concept, who thought the idea deserved “an accomplished novelist with an eye for the absurd and an ear for dialogue.” This is putting it mildly.

On reading the book once I learned of Buday’s exceptional writerly talents, and then I flipped to the beginning to read it again more carefully. Atomic Road contains a road trip in the temperamental season of fall, two unconnected but closely proximate murder plots, one intellectual rivalry, and one aloof intellectual; as well as love lost and love found amidst the Cuban Missile Crisis, the defining global emergency of the Cold War.

The year is 1962, and Atomic Road’s timeliness couldn’t be more exact. Its foundation consists of the shifting sands of what it might have meant to be a man, to be masculine. In 2018, personal pronouns seem to proliferate like fractals. Notions of binary gender constructs are all but annihilated, just so many fossilized specimens of bygone identity. The image of the moustachioed manly man with his Chevy gettin’ things done is laughable.

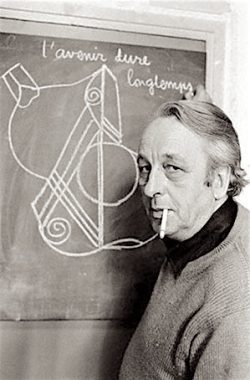

Under this light we join the story’s protagonist, infamous art critic Clement Greenberg, on a treacherous quest into the heart of the northern Great Plains during the Missile Crisis. The car radio forecasts doom by the hour. Greenberg rides with the mentally ill Marxist philosopher, Louis Althusser, who has been exonerated on an insanity plea after murdering his wife. Althusser is accompanied by a chaperone, the ex-commando Jean Claude, who turns out to be a contract killer.

Greenberg is feeling murderous too. A portrait of him has just been stretched onto a canvas, splattered with paint, and photographed for the cover of Art International, with his rival Harry Rosenberg standing to the side of the easel, declaring critical war on Jackson Pollock’s impresario. Rosenberg claims that Abstract Expressionism is out, Action Painting is in.

On a whim Althusser convinces Greenberg to drive with him from New York City to Saskatchewan, where Althusser will enter the world famous psychiatric hospital in Weyburn to undergo LSD therapy and, to his delight, wash it down with some good old electroshock.

Greenberg will carry on north of Regina to Emma Lake artist colony and fill a position there as critic-in-residence. Greenberg quietly plans on convincing Althusser to murder Rosenberg.

As the plot unfolds externally — a madcap assassin plot, to be sure — we peer inside Greenberg and explore the uncertain territory of his manhood. He is at turns arrogant, erudite, extremely anxious, and very sad.

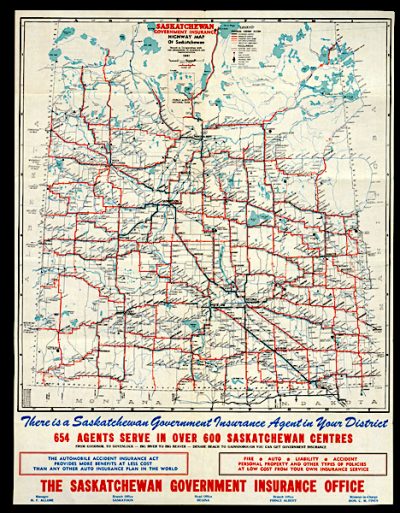

The narrative pulses forward on the unstable tension of this unlikely trio, whose fates have merged on an unlikely road trip to remotest Saskatchewan. They are a troika of uncertainty. We’re never sure whether they’ll get to Weyburn and Emma Lake or not. At times it looks unlikely. An episode with a roadmap represents a succumbing to and declaration of war on the vicissitudes of the protean world. After a comic attempt to ditch Jean Claude, Greenberg observes Althusser “enjoying the map’s panic, that to him it wasn’t a map at all but a swan or an albatross.”

The window is open and Althusser lets the map go. In the rearview mirror Greenberg sees the map “get scudded away in a tumble of white.”

Greenberg kindly rebukes Althusser, stating that it was their road map. “Maps are for sheep,” Althusser says, dismissively, “we proceed via the pelvis,” and then he gives the air a single little hump. His gesture asserts the novel’s double-barrelled exploration of masculinity and emasculation.

Atomic Road is at bottom an explosive road story. The road’s necklace of unpredictable novelty jangles in key with themes of gender destabilization and performance, ever shifting like Buday’s “tectonic clouds.” As Bakhtin would have it, in a road novel “the road is never really a road, but always suggests the whole, or a portion of, ‘a path of life.’”[1]

At the novel’s start, Greenberg is in a Shell station restroom projecting his erudition onto the Shell logo. For him it represents an altogether different kind of fuel. “[A] scallop, symbol of St. James and the pilgrimage to Santiago de Compostela,” he thinks, and considers his own trip a pilgrimage.

But I would hardly call a murder plot a pilgrimage. If there is one, it is not on the road. This is a deft symbolic inversion. The site, a gas station restroom, performs like an angled mirror reflecting the appropriate thematic concerns westward.

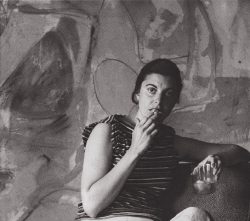

As the narrative propulsion intensifies and the lug nuts of the story start to loosen, a journey unfolds in retrograde along the circuits of Greenberg’s memory. It’s as if we were looking through a peephole into a motel room, the seedy interior miniaturized and flaring out in all directions. In the book’s world, Helen Frankenthaler is not only his friend, but his former lover with whom he is still in love. He dwells on his intellectual vocation and his drygood merchant father’s early misgivings about it. Finally, Greenberg broods on his failed first marriage and his estranged son, David, who lives in a shack and fashions effigies out of wax.

All these recollections are plaited with flashbacks of Greenberg in dialogue with his New Age analyst. If Greenberg embodies interior questions and uncertainties about his sexual, professional, and paternal validity, Althusser is a figuration of similar destabilized categories. He externalizes them. Greenberg is stoic in his anxiety. Althusser is visibly frail. His past is homicidally shameful. His behaviour is argumentative in a cryptic and riddling way, while his movements are erratic and unpredictable.

As they travel, reports filter in via radio, television, and newspaper about the Cuban Missile Crisis — a kind of Mexican standoff, but without the bandoliers and revolvers. Instead, Kennedy, Khrushchev, and Castro are flexing with nukes. It is hard to think of anything more phallic and destabilizing.

Greenberg’s profession as art critic locks with the novel’s visuality. Images can be decidedly masculine. Erupting mushroom clouds threaten. A factory stack pumps “black fists of smoke.” The windshield wipers on the blue Dodge Dart Seneca “ejaculate windshield wiper fluid.” As Greenberg drives, he likes “the sensation of the world coming to him, of sitting like a king on his throne and watching it approach on its knees.”

Since he looks at pictures and writes about them for a living, Greenberg sees the world in many shades and in scrupulous detail. The action in Atomic Road — physical, spatial and psychological — constantly shifts, giving the book a frenetic yet meditative quality. One scene in particular establishes the novel’s tipping and tilted world. Clement and Louis stop off at Niagara Falls so Louis can pour his wife’s ashes into the rushing water:

As Greenberg and Althusser stepped from the taxi they felt the vibration of the falls, the pavement trembling with a subterranean palsy. A vibrumble, thought Greenberg, pleased with the neologism. There were few things he enjoyed more than coining a new word. He inhaled the chill mist. Fragments of rainbow hung like cathedral glass arrested in mid-collapse.

Here we see the spectacular through Greenberg’s eyes. His command of language reifies the touristic space, which is itself a product, a commodity of automobilized society. He is cocky about his eloquence. With the precision of his sight, subtle use of words, and lyrical imagination we get the image of cathedral glass arrested in mid-collapse — a breathtaking picture that also suggests the fragility of Greenberg’s self-confidence.

In the same scene, Althusser externalizes Greenberg’s anxiety with tactics that distort his identity. To avoid Jean Claude they have put on disguises. Louis is in full drag. The two even kiss as a decoy when Louis spots Jean Claude hot on their heels. The Niagara Falls scene is a thematic prelude to the rest of the novel. As the trio carry on, the momentum begins to feel non-linear, as if they were being pulled to the side and downwards.

The eye of the vortex is a tavern called Smokey’s in Haaden Creek, North Dakota, south of the border with Saskatchewan. This geographical position is significant. It figures geopolitically and not without irony. Missile silos dot the state of North Dakota. We learn in John O’Brian’s introduction that Saskatchewan has the only elected socialist government in North America. Some of the provinces’s social programs, O’Brian writes, are financed by profits made from uranium mining.

Clement, Louis, and Jean Claude arrive at Haaden Creek in need of fortifiers. They settle in at Smokey’s Tavern, which is full of rapt farmers watching television while a grave Walter Cronkite covers the latest developments of the Crisis on television. First Althusser shouts “Viva la revolución!” and hammers his fist on the table. Their jug of beer shatters on the floor. Then Althusser cuts into Cronkite’s update, which is showing Kennedy, Khrushchev, and Castro. “Goats and monkeys! Off with their heads!” he screams, and adds, “It is the Rapture! We will all go up together. Let me kiss you. Let me kiss you all!”

Althusser’s outburst sets in motion an unexpected chain of events for these travellers. “Call Swen,” mutters a bald man named Bob, dressed in a tight shiny green jumpsuit zipped to the neck, seen by Greenberg as an “androgynous creature lacking both eyebrows and eyelashes.” He has eyes with “a fish-like flatness” to them. The trio are taken to a bomb shelter to be interrogated. Greenberg watches as Bob climbs down into the shelter “with the slow and exaggerated litheness of Marcel Marceau pretending to descend a ladder.”

Soon after, the town’s silver-tongued deputy arrives. It is Swen, Ciceronian agent of the Righteous and Infallible American Way, McCarthy style. He accuses the three of being agents provocateurs, with their talk of revolution and their “homosexual overtures.” Swen is even convinced the Domino Theory is applicable to Canada: “Yet I fear the domino is poised to fall, and once one goes so too will the rest of the provinces, Alberta to the West and Manitoba to the East, and after Alberta then British Columbia, and after Manitoba then Ontario.”

Geopolitical events transpire in real time. The spectacle of the Crisis infiltrates all spaces, like God in the Old Testament. The implications of this are soon revealed. They learn later, while they are in custody in Smokey’s bomb shelter, that the media had “wheeled out the Big Bertha of terms: Armageddon:”

The army, navy and air force had all been mobilized and the generals were meeting. The Pentagon was on code red. Helicopters and Grumman S2Fs were dropping sonobuoys and triangulating the echoes to hunt Soviet subs. The shadow of apocalypse was upon them.

There is another “subterranean palsy.” A military cavalcade rumbles by Smokey’s over the creek’s iron bridge. These three have stumbled into a Cold War crucible observed by Greenberg, the professional art critic, in what could only be an acid flashback:

[H]e had a vision of a photographer’s darkroom lit with infrared light as a picture emerged from the sloshing brew of a developer’s tray, the image gradual, advancing and then retreating in tints and lines, to finally coalesce as Greenberg’s own face gazing as enigmatic and ageless as an Olmec head, except that even as he watched his eyes opened and focused on him, his own eyes viewing him from his own eyes, a Möbius strip mirror in which he looked simultaneously outward and inward.

Here in Smokey’s, I think, is the crux of Atomic Road in all its ambiguity. All the novel’s themes and motifs rebound within this Möbius strip mirror. The provincial merges with global military strategy. Anarchism caroms off nihilism and collides with strident patriotism. An aesthete’s confrontation with the rustic produces an unforeseen synthesis of log joists, John Deere hats, psychedelia, memories of French mimes, and frontier glibness.

Is it necessary to stoop to comparisons or parallels, to lump this fine new work in with the old? Well, I admire the books that Atomic Road reminds me of. It is an unpredictable concoction, a strange and delightful combination. It invokes Philip Roth with its cast of odious middle-aged intellectual men and Roberto Bolaño in its use of historical figures in fictional (often criminal) scenarios. The sneaky French potboilers of George Simenon or Marcel Allain come to mind, along with the intrigue and anxiety in Graham Greene’s books.

Atomic Road is a fine-tuned high-performance machine. Well-researched without being pedantic, hilarious without slipping into farce, and historical without the repetitive argumentation of historiography, Buday succeeds in doing what good novelists try to do. They propose that an underlying coherence exists beneath the chaos of social interaction and human folly, beneath weather and landscape, beneath our political frailties and our technological might.

*

Dustin Cole was born in Hinton, near Jasper, and raised in the town of High Level, an isolated community in northwestern Alberta, and received his B.A. in history from Simon Fraser University. He has authored the collection of oneiric poetry Dream Peripheries (Vancouver: General Delivery, 2015), and is writing a novel, Notice, set in contemporary Vancouver, concerning a student served with a Notice of Eviction by his shady landlords, his subsequent insolvency, and his realization that Vancouver is far from a romanticized “Super Natural” idyll full of promise and contentment. Dustin Cole lives in Vancouver.

*

The Ormsby Review. More Books. More Reviews. More Often.

Reviews Editor: Richard Mackie

Reviews Publisher/Designer: Alan Twigg

The Ormsby Review is a journal service for serious coverage of B.C. books and authors, hosted by Simon Fraser University. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Robin Fisher, Cole Harris, Wade Davis, Hugh Johnston, Patricia Roy, David Stouck, and Graeme Wynn. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. As of September, 2018, Provincial Government Patron: CreativeBC

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

[1] From an essay by Mikhail Bakhtin, “Forms of Time and the Chronotope in the Novel,” in M.M. Bakhtin and Michael Holquist, The Dialogic Imagination: Four Essays (University of Texas Press, 1981), p. 120.

Weyburn Mental Hospital to where Louis Althusser drove from New York to undergo LSD therapy and electroshock treatment in 1962.

Leave a Reply