#27 Jilek-Aall, Louise

November 26th, 2015

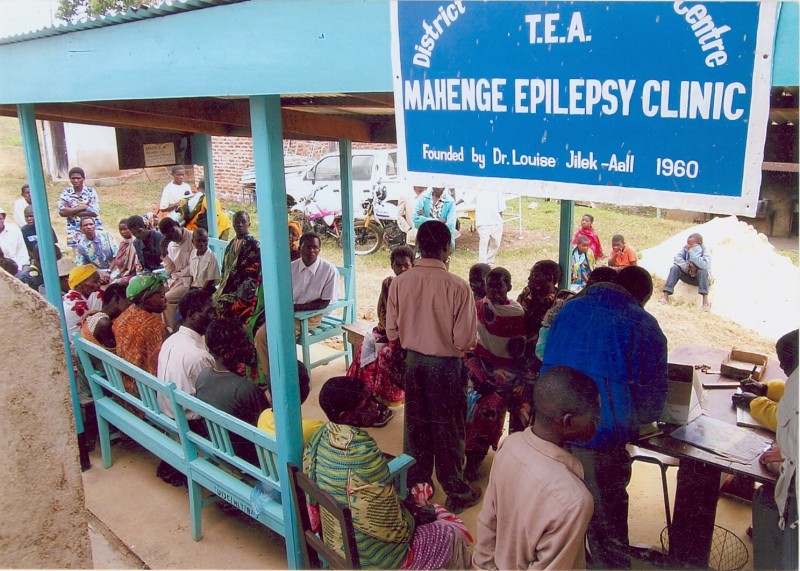

LOCATION: Mahenge Epilepsy Clinic, Mahenge, Tanzania; south east of Singida, in the miombo woodland bio-region, Morogoro Region of Tanzania. 8° 41′ 0″ South, 36° 43′ 0″ East. 289 kilometres from Dar es Salaam.

Louise Aall was born in Oslo, Norway in 1931. In 1959, after gaining diplomas in medicine and in tropical medicine, she went to Africa and worked for three years as a physician in Tanganyika (now Tanzania) and the Belgian Congo during the worst of the Belgian Congo civil war. In the Mahenge mountains of the Ulanga district of Tanganyika she discovered that the people of the Wapogoro tribe suffered from a convulsive disorder, called kifafa in Swahili, a form of epilepsy. There was a drastically high prevalence of epilepsy within this population. Seeing the misery of these patients, Dr. Aall founded the Mahenge Epilepsy Clinic in 1960. It has remained in operation ever since. [In 1963 Dr. Louise Aall married the Austrian physician Dr Wolfgang G. Jilek, who had accompanied her to Tanzania in that year, and she adopted the marital surname Jilek-Aall.]

QUICK REFERENCE:

As a student in Oslo, Louise Aall was inspired by Albert Schweitzer’s visit to Norway when he received his Nobel Peace Prize and he delivered a speech in the auditorium of Oslo University on November 4, 1954. After she gained her medical degree in Zurich, she studied tropical medicine in Basel. This led her to conduct a research project in Africa in 1959, working as a doctor in Tanganyika. She subsequently received the Henri Dunant Medal from the Red Cross for her distinguished service as volunteer doctor affiliated with the United Nations during the horrific Congo civil war in 1960. She was asked by the Red Cross to go to the war-torn region after the Belgian physicians had suddenly fled the country.

After her grueling service as a Red Cross doctor in the hottest part of the Congo, Louise Aall worked with Albert Schweitzer at his Lambaréné hospital in what is now Gabon.

After an improvised departure from the Congo on a freighter (after she had been airlifted onto the deck of the freighter by a helicopter, much to the surprise of the freighter’s captain and crew), she decided to travel up the Gabon River and visit Dr. Albert Schweitzer’s jungle hospital in Lambaréné, Gabon. “And what can I do for you,” Dr. Schweitzer asked the young lady. She nervously blurted out, “I want to learn how to extract teeth in the jungle.” He was very impressed that she was already a bush doctor and asked her to stay. She was exhausted after being one of the few physicians in a 300-bed hospital in a remote part of the Congo–and she later recognizes she likely had PTSD–but she consented to his request.

For the better part of a year Dr. Aall remained with Schweitzer, befriending him and learning jungle medicine.

Almost 30 years later she recalled her apprenticeship in her memoir, Working with Dr. Schweitzer: Sharing his Reverence for Life (1990). “In my work,” she writes, “I am keenly interested in people who are role models and who serve as ego-ideals, especially for the young; but only a very few appear to be worthwhile models.”

Upon her return to work in central Tanganyika, she further clarified that outcasts in the Mahenge Mountains suffered from a severe form of epilepsy. Consequently she founded a makeshift clinic in the Ulanga district to specifically treat epilepsy patients and to educate their families about the disease. For much of the time she never heard her own name. She was known instead, far and wide, as Mama Doctor.

Initially the patients she saw were mostly from the Wapogoro tribe. They had hardly ever received medical treatment for epilepsy and suffered greatly from frequent seizures. Nearly all of the epilepsy sufferers were feared and shunned, even by their own family members, as it was believed that seizures were mostly caused by evil spirits as punishments for uncivil behaviour. Frequently these kifafa sufferers died from the burns suffered when falling into domestic fires or through drowning when fetching water or fishing in the rivers.

Seeing so many patients arrive at the Catholic mission dispensaries for treatment of burns and other injuries suffered during their seizures caused Dr. Aall to recognize there was an abnormally high prevalence of epilepsy in the region.

“In the Western world of today,” she has written, “one does not often encounter persons suffering from tonic-clonic seizures for years without medical treatment. However, in many non-Western rural areas where treatment facilities and health professionals are scarce, such persons suffer convulsive seizures, often with post-ictal confusion and fugue states. As I observed in Mahenge, they may die in status epilepticus, or develop severe depression and psychotic states with Parkinsonian symptoms.”

At the Mahenge Clinic, patients and their families first were given education about epilepsy and its treatment. Treatment was commenced only after full cooperation by patients and their families had been established. During her early career, Dr. Jilek-Aall was repeatedly told by other medical authorities that her patients would never have the self-discipline necessary to adapt to a regimen of medication; she proved them wrong.

Due to easy implementation and cost effectiveness, Phenobarbital was mostly prescribed. In other selected cases, Phenytoin or Primidon were used. About 200 kifafa patients were examined and treated during the first two years of the clinic. Gradually, due to Dr. Aall’s efforts, epilepsy sufferers were less stigmatized and they were not invariably forced to live as outcasts.

In 1972 the epilepsy clinic established at the Dispensary of the Kwiro Catholic Mission in Mahenge was taken over by the Tanzanian Government and placed under the newly established Mental Health Center of the Mahenge Government Hospital. The Mental Health Centre was staffed with one nurse who had to treat patients with mental illness and epilepsy. From then on, basic medication was provided for by the Tanzanian Government, as in other public hospitals.

The Government was not always able to supply sufficient antiepileptic medication so, from time to time, donations were made by Dr. Jilek-Aall and other Canadian donors she could find. The Mental Health Centre was inundated with epilepsy patients while the number of purely psychiatric patients remained minimal.

Dr. Jilek-Aall has continuously worked to improve the Mahenge Epilepsy Clinic and initiated research into epilepsy with teams of specialists from Canada, Austria, Germany and Tanzania. These specialists have scientifically confirmed the existence of a unique form of epilepsy, “head nodding syndrome,” first described by Dr. Jilek-Aall in the 1960s. Efforts have been undertaken to prove the likely source for “head nodding syndrome” is a parasite which is found in many tropical regions, Filaria worm (Onchocerca volvulus).

Mahenge patients receive their monthly supplies of medication, 2005, administered by the Tanzanian government.

Also a trans-cultural psychiatrist and anthropologist, Dr. Jilek-Aall has been a member of the UBC Faculty of Medicine since 1975. She speaks Norwegian, English, German, French, Spanish, Swedish, Danish and Swahili.

Her “bush doctor” experiences were first recalled in the book, Call Mama Doctor (1979), covering the years from 1959 to 1979. It was redesigned and enlarged with new chapters, drawings and photos, and released as Call Mama Doctor: Notes from Africa (2009) covering the years 1959 to 2009. Working with Dr. Schweitzer has been published in China, Japan and Hungary but Dr. Jilek-Aall’s books are almost unknown in North America. Too self-effacing to describe her life in heroic terms. as well as disinclined to pursue any marketing, Dr. Louise Jilek-Aall lives with her husband, Dr. Wolfgang G. Jilek, in Tsawwassen. Due to her age, she is no longer able to fly to Africa but she remains intensely involved in maintaining the effectiveness of the Mahenge Epilepsy Clinic.

BOOKS:

Call Mama Doctor: African notes of young woman doctor , 1979 0-88839-025-4

Working with Dr. Schweitzer: Sharing his Reverence for Life (Hancock House 1990) 0-88839-209-5

Call Mama Doctor: Notes from Africa (Aldergrove West Pro Publishing, 2009) $24.95 978-0-9784049-2-5

Professional biographical information:

Dr Louise Jilek-Aall holds the Doctorate in Medicine of the University of Zürich; the Diploma of Tropical Medicine of the Swiss Tropical Institute, Basel; the Diploma in Psychiatry of McGill University, Montréal; and the Master of Arts degree in Cultural Anthropology of the University of British Columbia, Vancouver. She is a Fellow of the Royal College of Physicians of Canada. She has been a member of the Faculty of Medicine, University of British Columbia, Vancouver, Canada, since 1975. She started her private practice of psychiatry in Canada in 1966, starting in Chilliwack, B.C. After she and her husband moved to Vancouver, she continued her private practice in Abbotsford, Ladner and Tsawwassen. She also travelled as a psychiatric consultant and a teacher for young doctors, nurses and social workers in hospitals and health centres in northern British Columbia, chiefly Prince Rupert and Haida Gwaii (when it was known as the Queen Charlotte Islands), mainly treating First Nations patients, until her retirement in 2012 at which time she became Clinical professor Emerita of psychiatry. For much of her medical career she has maintained contact with her former teachers Prof. Manfred Bleuler, of Zurich, and Prof. Viktor Frankl, of Vienna. She has continued to correspond with friends and colleagues in Africa and other countries, still overseeing operations in Mahenge from afar.

Dr. Jilek-Aall never had any serious health problems in Africa, not even when making her ‘house calls.’

Dr. Jilek-Aall has undertaken extensive, ongoing clinical research on epilepsy in Tanzania. She conducted the joint Canadian-Tanzanian research project on epilepsy with a grant of the International Development Research Centre, Ottawa. In the years 2003, 2005, and 2009, she continued the research on epilepsy and its causes with a team of specialists from Canada, Austria, Germany and Tanzania, at the Mahenge Epilepsy Clinic where now over thousand patients receive treatment. One of the results of this research was the confirmation by EEG and video of a separate form of epilepsy (“head nodding syndrome”) which had already been described by Dr Jilek-Aall in the 1960s.

Dr Jilek-Aall is recipient of the Ambassador Award of the International League Against Epilepsy. Besides her epilepsy research, she has conducted transcultural-psychiatric investigations in East Africa, the Caribbean, South America, Southeast Asia, Papua New Guinea, and among North American indigenous and ethnic populations. As a volunteer psychiatrist she also worked in 1988 in United Nations-supervised refugee camps in Thailand.

In addition to her books, Dr. Jilek-Aall is the author or co-author of hitherto 97 articles and chapters in scientific journals and books. She held guest lectures at universities and institutes in North America, Mexico, South America, Europe, Japan, China, Thailand, and in Africa.

Shortly after their marriage, the Jilek-Aalls immigrated to Canada; working together in Canada and overseas.

Her husband, Dr. Wolfgang G. Jilek, psychiatrist and anthropologist, has been a member of the Faculty of Medicine of the University of British Columbia since 1974; in the 1980s he rendered international service as Mental Health Consultant for the World Health Organization and the UN High Commissioner for Refugees. Their daughter Martica Ilona Jilek, R.N., is a specialized clinical nurse; from 1992 to 2009 she accompanied her mother to Tanzania to assist at the Mahenge Epilepsy Clinic and the epilepsy research teams.

Louise Jilek-Aall’s husband and fellow physician fellow Dr. Wolgang G. Jilek is also an avid photographer. He took this photo.

Dr. Jilek-Aall’s epilepsy clinic was maintained with the cooperation of a local Catholic mission nurse and African volunteers who were accorded regular consultative correspondence with Dr. Jilek-Aall. Initially she was only able to secure a consistent supply of medication from abroad. In 1989, the clinic was reinvigorated by the interest shown by the Tanzanian neurologist Dr. Henry Rwiza. Having completed his training in the Netherlands, Dr. Rwiza conducted an epidemiological survey of convulsive disorders in the whole of the Ulanga district. Funded from the Netherlands and conducted under the auspices of Dr. Rwiza’s former teacher, epileptologist Dr. Harry Meinardi, this study confirmed Dr. Jilek-Aall’s suppositions made some 30 years before. Scientific evidence confirmed that the prevalence of epilepsy in Mahenge was about ten times higher than in Western countries.

The Mahenge Epilepsy Clinic was reorganized and expanded in 1990 when Dr. Jilek-Aall revisited the area to plan a research project together with Dr. Rwiza into the ethiology and clinical characteristics of Kifafa and the reasons for the high prevalence of convulsive disorders among the Wapogoro. The research was approved and funded for three years by the International Development Research Centre (IDRC) of Canada in 1991 and carried out by a group of scientists from the University of British Columbia Canada and from the University of Dar-es Salaam Tanzania under the leadership of Dr. Jilek-Aall in cooperation with Dr. Rwiza.

The IDRC research group found many reasons for the high prevalence of epilepsy, as one finds in most tropical regions such as: malaria and other parasitic infestations, meningitis and other infections, perinatal traumas, infantile gastroenteritis and other illnesses leading to fever convulsions etc. But it was felt that these general causes could not explain the unusual high prevalence of the Kifafa affliction which often was a very severe form of epilepsy, accompanied by other neurological symptom and quite frequently by mental problems.

Nearing the close of the research project, Dr. Jilek-Aall found it striking that so many of the Kifafa sufferers showed signs of being infested with the Filaria-worm Onchocerca volvulus. She consequently learned that epidemiological research carried out by parasitologist from the University of Dar-es Salaam had shown that Mahenge mountains are the area of the heaviest infestation of onchocerca volvulus of the whole country of Tanzania. Attempts to eradicate this worm have been undertaken by the World Health Organization in many parts of Africa because this Filaria is proven to be connected to a better known malady known as “river blindness.”

Since 1991 the Mahenge Epilepsy Clinic, situated in the middle of the research area, steadily accepted new patients and had a patient population of more than 1,000. For years, Jilek-Aall had been told by medical specialists working in Africa that African patients were part of their problem, because were not sufficiently able to adopt a regime of care. “Contrary to general prediction,” she writes, “most patients have turned out to be quite reliable in taking the medication regularly as prescribed, for years on end.”

Consequently the people of Mahenge have learned that the affliction of Kifafa can be controlled with western medicine. Many of the patients are accepted back into their families due to the prescriptions, mostly with Phenobarbital and Phenytoin. During several decades of operation, government agencies were not able to fully pay for the large amount of medicines necessary and so the clinic was often dependant upon funds provided by Dr. Jilek-Aall and other overseas sources.

A young German neurologist named Dr. Andrea Winkler, who had read Louise Jilek-Aall’s articles, visited the Mahenge clinic in 2003 while Jilek-Aall was refurbishing the dilapidated clinic quarters. Encouraged by Dr. Winkler’s interest and collaboration, Jilek-Aall was able to organize another research team whose thorough investigations have led to the clear indication that most kifafa sufferers at Mahenge are infested with the parasite Onchocerca volvulus.

“We saw children and juveniles who displayed the peculiar syndrome that local people call amesinzia kitchwa, meaning ‘nodding the head,’” wrote Jilek-Aall. “It usually starts in childhood, and the local people know that the afflicted child will sooner or later develop epileptic seizures. I had already observed this head-nodding syndrome in children of the Mahenge region in 1960, and had verified in follow-ups that they indeed develop grand mal epilepsy. At that time I had described this syndrome in detail in scientific articles and congresses; however, my reports had met with disbelief.”

In Tanzania, sufferers of epilepsy had been called maskini, meaning “the useless ones.” They were expected to be humble and accept the poorest food and clothing, resigning themselves to subjugation and maltreatment, effectively outcasts. But the rudimentary Mahenge Epilepsy Clinic has engendered hope and dignity.

During the fifty years the Mahenge Clinic has been operating, attitudes towards epilepsy has evolved significantly. Jilek-Aall has introduced a rehabilitation program of agrarian and reforestation work for epileptic patients, although these initiatives are now under threat due to lack of funding.

International epilepsy expert Dr. Erich Schumutzhard at the Medical University of Innsbruck, fluent in Swahili, has joined Jilek-Aall’s team, providing invaluable access to funding and research. Schumutzhard, Winkler and Jilek-Aall met at Mahenge in 2005, along with Jilek-Aall’s daughter Martica, who recorded the curious syndrome of head nodding on video.

Research conducted at Mahenge has been published in scientific journals and have led to international recognition of head nodding as a new epilepsy syndrome.

===

Fifty Years: Epilepsy Clinic & Research in Mahenge

Excerpts from a Summarizing Report, December 2010, written by Dr. Louise Jilek-Aall

In 1989 the Tanzanian neurologist Dr.Henry Rwiza returned to Tanzania after completing his specialist training in neurology in the Netherlands under my friend Prof. Harry Meinardi, a renowned neurologist specialized in epilepsy. Prof. Meinardi had made Dr Rwiza aware of the epilepsy clinic in Mahenge, with the result that Dr. Rwiza conducted an epidemiological survey of convulsive disorders in the Ulanga district in which Mahenge is situated. To his great surprise he confirmed what I had stated some 30 years earlier, namely, that the prevalence of epilepsy in Mahenge was much more than ten times higher than what is known from Western countries.

The Mahenge Epilepsy Clinic was expanded in 1990 when I revisited the area to plan a research project together with Dr. Rwiza and Dr. William Matuja, both neurologists at the University Hospital in Dar-es Salaam, to investigate the etiology and clinical characteristics of kifafa and the reasons for the high prevalence of convulsive disorders among the Wapogoro people. This research was approved and funded for three years by the International Development Research Centre, Canada (IDRC) in 1991 and carried out by teams of scientists from the University of British Columbia, Canada, and from the University of Dar-es Salaam, Tanzania, under my leadership in cooperation with Drs. Rwiza and Matuja. The research team found many possible causes of epilepsy, as exist in most tropical regions; such as, birth trauma, parasitic, bacterial or viral infections of the brain, head injuries, or genuine epilepsy with hitherto unknown causes or due to a genetic disposition. But I felt that these general causes could not explain the very high prevalence of the affliction in this population. Kifafa is a severe form of epilepsy, often associated with other neurological symptoms and, if untreated, with mental problems, hence chronic epilepsy sufferers are usually treated at Mental Health Centres in rural Tanzania.

Since 1991 the Mahenge Epilepsy Clinic has accepted new epilepsy sufferers and has at times been treating more than one thousand patients. Contrary to general prediction, most patients have turned out to be quite reliable in taking the medication regularly and as prescribed, for years on end. Their compliance and the cooperation of their families have been possible through the continued health education on epilepsy by myself, Dr. Matuja, and the clinic nurse. The people of Mahenge have now increasingly experienced how the terrifying affliction of kifafa can be controlled by modern medicine. During the 50 years the clinic has now been operating, the general attitude towards epilepsy among the local population has changed and many of the well controlled patients have been accepted back into their families and are able to live a life close to normal, even though only the basic antiepileptic drugs phenobarbital, phenytoin, and now carbamazepin, are available through the Tanzanian government.

For a long time I had found it striking that many of the kifafa sufferers were also infested with the filaria parasite. Just at the end of our research project in 1994, I found out that epidemiologic research carried out by a parasitologist researcher from the Aga Khan Hospital of Dar-es Salaam, had shown that the Mahenge mountains are the area of the heaviest infestation with Onchocerca volvulus in Tanzania. I therefore began to plan for a new research project and was searching for funding to organize a research team that could take up this challenge, together with a university research laboratory with access to modern brain investigations. It took years to realize such an undertaking.

In the meantime the nurse at the Mahenge Epilepsy Clinic has been carrying on with the difficult task of maintaining regular treatment for hundreds of patients suffering from epilepsy.

“The first motorbike which I donated to the clinic in 1992,” recalls Jilek-Aall, “so that the nurse could reach patients living scattered all over the mountain area, became completely out of repair. I was able to solicit the donation of a new motorbike in 2003 through a Rotary Club in Canada.

“I then discovered that the clinic had been moved to a place outside the hospital among dilapidated storage sheds. Together with local people and friends from Canada, I restored the clinic building and the waiting area to an acceptable degree during my visit in 2003.

“In the summer of 2005, I was finally able to get together sufficient funds for a team of researchers to accompany me to Mahenge for an in-depth aetiological investigation of the high prevalence epilepsy there. Besides myself, members of the research team were the internationally known expert in tropical neurology Prof. Erich Schmutzhard (Med. Univ. of Innsbruck, Austria); the neurologist with African experience Dr. Andrea Winkler (Univ. of Munich, Germany); Prof. William Matuja (Univ. of Dar-es Salaam, Tanzania), long-standing co-researcher in Mahenge, and senior medical students.

“In intensive field work we were able to examine a great number of the clinic patients, together with healthy controls, and collect biological materials, such as blood, cerebrospinal fluid and skin samples, to take back to Europe for further sophisticated laboratory tests. We also selected some of the patients and controls for electro-encephalographic and magnetic resonance studies at the Aga Khan Hospital in Dar-es Salaam.

“Our examinations confirmed the presence of a new type of epileptic seizure in children, the AHead Nodding Syndrome@ leading to convulsive attacks in later life. I had already observed and described the Head Nodding Syndrome in the 1960s. As it was unknown in Western countries, the existence of this epilepsy syndrome had then been ignored. However, the Head Nodding Syndrome is today accepted and attracts international attention among experts.

“Our research has been continued with another field investigation in 2009. Unfortunately, the costs of the complicated investigations have been high and we are still struggling to get sufficient funds in order to complete the study of the possible connection between onchocerciasis and epilepsy..

“Another challenge is how to help the Mahenge Epilepsy Clinic to continue with adequate treatment for the many epilepsy sufferers. Prof. Matuja, as president of the Tanzania Epilepsy Association, is trying to get the Tanzanian Government to provide modern medication for the patients suffering from epilepsy. He is also asking for an additional nurse to be posted at the Mahenge Epilepsy Clinic to assist the mental health nurse in coping with the treatment for a growing number of epilepsy patients. Dr. William Matuja made this possible.

“Another challenge is how to help the Mahenge Epilepsy Clinic to continue with adequate treatment for the many epilepsy sufferers. Prof. Matuja, as president of the Tanzania Epilepsy Association, is trying to get the Tanzanian Government to provide modern medication for the patients suffering from epilepsy. He is also asking for an additional nurse to be posted at the Mahenge Epilepsy Clinic to assist the mental health nurse in coping with the treatment for a growing number of epilepsy patients. Dr. William Matuja made this possible.

“One of the problems people with epilepsy are facing, is the general believe in Tanzania, as in many other parts of the world, that people with epilepsy, even when under treatment, are not fit for employment. In Tanzania, people with epilepsy together with other persons suffering from chronic illnesses, are called maskini, meaning the useless ones, the ones who are a burden to others. They are expected to be humble, and to accept without protest the poorest kind of food and clothing, and to endure any mistreatment people may expose them to. But in reality there is no reason why a treated epilepsy patient could not work. I have observed a few of the recovering patients in Mahenge who themselves had secured a job which earned them a small amount of money. The pride and prestige patients felt when being able to contribute something to their family, was of immeasurable emotional benefit for them. For a long time I was therefore trying to find a way of helping recovering epilepsy patients to secure employment.

“The Catholic Seminary Kasita is close to Mahenge village where the Government Hospital and the Mahenge Epilepsy Clinic are situated. This seminary has large vegetable gardens, a well established reforestation project, and some farm animals, and needs workers for a variety of jobs. In 2005 the Rector of Kasita Seminary agreed to my suggestion of hiring some of the patients from the epilepsy clinic whom the nurse considered capable of doing this kind of work, as I offered to pay part of their wages.

“On my return to Mahenge in 2009 I found out that only a few of the patients had been able to stay on the job for any length of time. Interviewing the patients involved, their non-epileptic co-workers, and the overseers, it became clear to me that such a rehabilitation program needed a firm structure to enable epilepsy patients to adjust to a regular work schedule and to be integrated into a work team.

“I therefore prepared a program for a three-year pilot project for which a group of suitable recovering clinic patients was selected; ten patients at the time to be working full time, any drop-out to be replaced by another candidate. They were paid the same wages as other workers, which was made possible through donations by myself and Canadian friends, facilitated by the Savoy Foundation Epilepsy in Quebec, Canada. The working patients were followed closely by a supervisor who was to address any arising problems, report to me and receive my advice. Most of the chronic epilepsy patients had to be helped to overcome their low self-esteem, timidity, and despondency, due to the psychological trauma they had suffered when they were stigmatized as the ‘useless ones’. The objective was that recovering epilepsy patients learn to take responsibility for regular job performance, to be accepted as equals by other workers; so that later-on they will be able to find employment elsewhere. “We now have been able to demonstrate that most participants in this pilot project of three years, are capable of working in gainful employment after going through a period of learning and adjustment. The quality of life of these patients and their acceptance by family and community has greatly improved. The success of this pilot project has shown that recovering epilepsy patients are able to become productive members of the community. This should encourage the Tanzanian authorities to promote the establishment of a permanent work rehabilitation centre for recovering epilepsy patients, in connection with the Mahenge Epilepsy Clinic and the Tanzania Epilepsy Association chaired by Prof. Matuja.”

Fundraiser Ken Morrison (far right) accompanied Dr. Jilek-Aall during her most recent visit to Mahenge.

***

TAX DEDUCTIBLE DONATIONS TO SUPPORT DR. JILEK-AALL’S WORK CAN BE SENT TO:

Provision Charitable Foundation

c/o Kenneth A. Morrison

Chartered Accountant

Provision Chartered Professional Accountants

120 – 10451 Shellbridge Way

Richmond, BC

V6X 2W8

604-273-6601

Email: kmorrison@provisiongroup.ca

Leave a Reply