How to live on planet earth

In 1995, a chance meeting in the Albuquerque airport led Trevor Carolan deeper in the forest of zen.

May 03rd, 2016

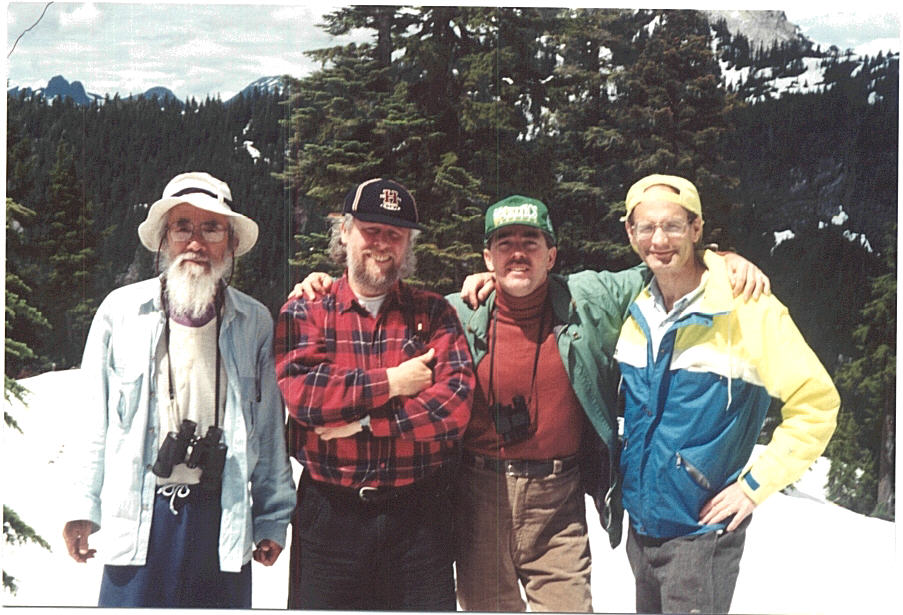

Trevor Carolan hiking with poets Nanao Sakaki and Ed Varney north of Grouse mountain, 1995.

Now Carolan has recalled his meetings with a remarkble man–Nanao Sakaki–in New World Dharma.

Trevor Carolan’s first encounter with the Zen poetry of Nanao Sakaki (1923-2008) was back in 1985 when he heard Gary Snyder read an unforgettable poem entitled “Break the Mirror” by his friend Sakaki.

Five years later, Carolan wrote to Nanao and asked if he could include that poem in an anthology. Nanao graciously replied and mentioned he hoped to one day see British Columbia’s wilderness.

Then in 1995, when Trevor Carolan found himself standing in an Albuquerque airport line-up, he noticed a lively looking Japanese elder coming towards him. This stranger asked Carolan about his unusual, gnarly walking-stick. Something about the old man’s long white hair and beard seemed familiar.

“Nanao?”asked Carolan.

Sure enough it was him. The two men compared mythologies en route to Phoenix. It turned out that Nanao was meeting Snyder to go desert-walking near Tucson; and Carolan had just been desert-walking near Santa Fe.

“A few months later,” Trevor Carolan recalls in his new book, New World Dharma: Interviews and Encounters with Buddhist Teachers, Writers and Leaders (SUNY Press 2016 “Nanao landed in Vancouver with a backpack filled with outdoor gear: ice crampons, all-weather clothing, the lot. Ten memorable days followed, filled with snow-country hiking, herb-picking, rascally dharma talks, singing and chanting, joking with the kids, and living well. Nanao lived the dharma without talking about it much. Alas, even vagabond dharma bards need dental work, so Nanao and I collaborated on a piece of writing to pay some of Nanao’s bills.”

Joseph Roberts at Common Ground magazine originally published the following article called ‘How To Live On The Planet Earth.’

[Recalling his encounter with Allen Ginsberg on Cortes Island, Carolan’s new book also includes chapters on Gary Snyder, the Dalai Lama, Governor Jerry Brown and Lawrence Ferlinghetti, among others.]

=======

In 1945, Nanao Sakaki, a young radar officer in Japan’s Imperial Navy, tracked an American bombing raid headed successfully for Nagasaki. A short time later it was feared an earthquake or even a volcanic eruption had struck. Within days, Japan lay in unthinkable defeat. The nation’s samurai code demanded mass military suicide but, at American command, the emperor intervened to reverse the order. Radarman Sakaki was spared his life. Demobbed from service, he viewed atomic bombsites where human beings had been vaporized into shadows on cement. In revulsion at anything remotely connected to militarism, Sakaki abandoned mainstream society; since then, with but a brief war-end stint in publishing that introduced him to many writers, he has led a vagabond life in the tradition of Japan’s wandering Zen poet-storytellers. For five decades he has walked the length and breadth of the Japanese islands, writing poems and speaking out against nuclear technology and industrial degradation of the environment. In doing so, Sakaki emerged long ago as the underground leader of his nation’s anti-establishment culture—no small thing in Japan’s ultra-conservative society.

During the early l960s, Sakaki also befriended American writers Gary Snyder and Allen Ginsberg in Tokyo’s Shinjuku district and the three became lifelong friends. Snyder himself joined Sakaki in building a loose, ecologically-attuned agricultural community on a volcanic island in the East China Sea, and his account of this “Banyan Ashram” in Earth House Hold became a critical text in North America’s cultural revolution of the late ‘60s.

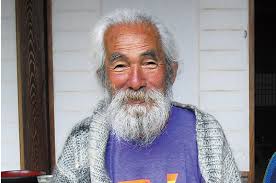

A vivid, weather-bronzed figure of seventy-two, Sakaki is an outstanding naturalist and a seasoned raconteur. A careful listener, he responds in good, musical English. His renowned humor is offbeat and infectious, yet there is no escaping his essential commitment to retooling the engines of modern culture, east and west.

Clear as creekwater and rich in nature wisdom, Sakaki’s poetry reads like medicine. His sense of presence is palpable and, almost unconsciously, people around him become more mindful of small communal responsibilities. It is difficult to describe precisely why this happens, but as Kolin Lymworth of Vancouver’s Banyen Books put it after an informal meeting, “Maybe Nanao just reminds us of that wonderful, wise older person we all seem to want, or need, to know.”

A recent hike in southwestern British Columbia’s Cascade Range offered Nanao an opportunity both to study the local vegetation and to elaborate further on what his work has to say to contemporary readers. En route, Sakaki relates that his passion for the wild began after reading Sir Laurens Van der Post’s classic Sands of the Kalahari. “I was so excited after reading it in the British Council Library that I couldn’t sleep for almost three days,” he says. “It was so new, so different. Here’s this hostile desert environment of lions and poisonous snakes. But Van der Post wants to understand the bushmen so much he finally comes to comprehend their philosophy, which is, “There is a dream that is dreaming us.” That’s very interesting to me! It’s also a little similar to Chuang Tzu’s butterfly dream in Taoism. So, as a young man, I had to think, what’s real?—because the evolution of this idea is that we must go with the dream; there is no other choice.

“In my work later on,” he continues, “I came in contact with Aboriginal people from Australia and Tasmania, and with Navajo people from the American Southwest who share almost this same idea. They live in timeless landscapes. That’s good for me, you see, because I’m crazy for wild landscape; always I wish to see the desert or volcanoes, or Alaska—big space, pure like [the] empty mind of Buddha. But Japanese business[es], for example, they are cutting down Tasmania’s forests for toilet paper. Terrible!”

“In my work later on,” he continues, “I came in contact with Aboriginal people from Australia and Tasmania, and with Navajo people from the American Southwest who share almost this same idea. They live in timeless landscapes. That’s good for me, you see, because I’m crazy for wild landscape; always I wish to see the desert or volcanoes, or Alaska—big space, pure like [the] empty mind of Buddha. But Japanese business[es], for example, they are cutting down Tasmania’s forests for toilet paper. Terrible!”

Sakaki is uncompromising in his defense of nature and has worked for decades at heightening awareness in Japan of his nation’s environmental policies. Few things have been as effective as his campaigns in the US when literary friends such as Snyder and, formerly, Ginsberg have rallied other prominent writers and artists to spotlight events needling Japan’s hyper-sensitive government. The external media pressure gets results.

“Our work for the twenty-first century will be reversing dams and big energy projects, replanting forests and cleaning water,” Sakaki says. “Already in Japan we are seeing legal cases where representatives of endangered species are suing the government. Japan, remember, still has rich wild spaces and two thousand black and grizzly bears, where in an island ecology like Britain’s they have disappeared.”

The critical shortsightedness typical of commercial planning leaves Sakaki at a loss. Remote Banyan Ashram for example, which drew visitors from around the world, is no more. Its low-tech success tempted Yamaha Corporation to offer local islanders the promise of jobs, enabling Yamaha to buy up the commune site for a glitzy tourist resort. Beauty is relative, however; what worked for remote islanders and back-to-the-land longhairs didn’t translate quite as well when visiting Tokyo honeymooners found themselves subject to periodic showers of volcanic ash. Now, both projects lie defunct.

Here, the inevitable question seems to be, “What does this say, then, of our Western myth about Oriental societies taking a longer, shrewder, generational view of things?”

“About Asia, I’m not so sure,” replies Sakaki. “The one example I have seen of this is among the Hopi people. They believe you shouldn’t make an important decision unless you think through its effects for seven generations. This means we have to imagine how we, and the consequence[s] of our actions, fit in the scale of things. If you think of trees, they usually live longer than humans: harvesting a tree can be like meeting your own great-grandfather. So rightly, we should think, what’s the appropriate thing to do here?”

Discussion of right practice and livelihood leads inevitably to the consideration of what role Buddhism, or Japan’s Zen path, may have for modern Western culture. Sakaki’s response is enlightening.

“Most Japanese Zen is uninteresting to me,” he says. “It’s too linked to samurai tradition—to militarism. This is where Alan Watts and I disagreed: he didn’t fully understand how the samurai class with whom he associated Zen were in fact deeply Confucian; they were concerned with power. The Zen I’m interested in is China’s Tang dynasty kind with its great teachers like Lin Chi. This was non-intellectual. It came from farmers—so simple. Someone became enlightened, others talked to him, learned and were told, ‘Now you go there and teach; you go here, etc.’ When Japan tried to study this, it was hopeless. The emperor sent scholars, but with their high-flown language and ideas they couldn’t understand.

“Today,” he adds, “many young people have lost their way. They’re looking for salvation, checking many gates. They read Zen anecdotes, see Zen pictures—it seems perfect! Then they think about achieving enlightenment, but it’s not so easy . . . About enlightenment I always say, just forget about it. Everybody’s already enlightened: people work at their jobs, the traffic moves along, so things are okay. A mother looks after her children, she makes their lunch, does her job well. That’s enlightenment: just doing a good job.”

“Today,” he adds, “many young people have lost their way. They’re looking for salvation, checking many gates. They read Zen anecdotes, see Zen pictures—it seems perfect! Then they think about achieving enlightenment, but it’s not so easy . . . About enlightenment I always say, just forget about it. Everybody’s already enlightened: people work at their jobs, the traffic moves along, so things are okay. A mother looks after her children, she makes their lunch, does her job well. That’s enlightenment: just doing a good job.”

For Sakaki, this version of right-mindedness extends without compromise to the last inning. “Once, hitchhiking in Southern Japan,” he says, “I met my cousin who told me my father was very sick. Okay, we went to the hospital where I saw my father. He was surprised to see me.

“I said, ‘So you are going to become Buddha!’ You see, in [the] Amida sect of my family we say that when you die, you’re becoming Buddha. My father, he kind of half-smiled. His face brightened. He said, ‘Yes, I’m going to become Buddha, looks like!’

“So when my friends tell me, ‘My father is sick, my mother is dying,’ I say, congratulations! They are becoming Buddha!

“That’s it,” he concludes. “When it’s time to sleep, just sleep; when you’re sick, just be sick; when you’re going to die, just die! Enlightenment!”

About the specific values that Buddhism may offer the contemporary West, Sakaki answers in terms of compassion.

“This is a big subject,” he responds. “Tibetan, Zen, Pure Land—there are many good gates in Buddhism to the empty space within. You see, in original Buddhism there is no competition, but Western society is strongly rooted in just this thing; it moves aggressively onward. Real compassion goes beyond human society—to animal life, trees, water, rock. It’s easy to relate to the environmental movement. Buddhism says we are all the same and the West, I think, is missing this. There is an Indian Sutra teaching—Paticca Samupadda—that discusses the perfect wholeness of all things and how they are joined. The Dalai Lama, Thich Nhat Hanh, the Diamond Sutra, they all talk about this.”

And the way to compassion?

“Slow down,” Sakaki smiles. “Slow down the metabolism, the whole mental image. Compassion is like a shadow—like the Hopi thinking seven generations on.

“After all, how we work out our difficulties is a social question, not spiritual or mental,” he explains. “As a society, if we have no vision, all we’re left with is bureaucratic process. That’s too sad! Artists, poets have a responsibility for landscape, for wild nature. As a poet I feel my poems are also Sutra, in the way that a painter’s good work is also drawing Sutra. And as listeners, if we meet a good poem, or discover a new landscape, we must have a good answer. In the end it becomes spontaneous, like question and answer. It’s like hearing good music, really; it calls to me, I start humming, moving—I find I’m dancing! That’s Zen: not thinking, not stopping halfway, not copying landscape but finally becoming the landscape.”

Deep Cove, BC

*

Nanao Sakaki’s Collected Poems were published in 2014.

Sakaki, Varney, Carolan, Arnold Shives, 1995. “Oriental people say two ways to escape and be happy. Downtown—very busy, crowded place. Just be lost among many people, stay in a slum. Another is in high places. Live in a mountain cave. I’ve tried both…Try walking mountainsides, the north. I love walking these places. That’s me personally. Probably there is no solution. It’s a good idea: no solution! Much wider perspective. If you have a solution, you’re trapped in solution network.” — Nanao Sakaki

Trevor, Thanks for the posting – both for the photos and the very fine explication of Nanao’s Zen.