#236 Fernie at War

January 21st, 2018

Fernie At War: 1914-1919

by Wayne Norton

Halfmoon Bay: Caitlin Press, 2017.

$24.95 / 9781987915495

Reviewed by W. Keith Regular

*

Works of history are matters of scale, a broad perspective over extended time (macro), or narrowly focused investigation (micro). In this age of globalism and its repudiation, as the current anti-immigration trend and national retrenchment evident in some quarters suggests, a contest of paradigms is expected.

Works of history are matters of scale, a broad perspective over extended time (macro), or narrowly focused investigation (micro). In this age of globalism and its repudiation, as the current anti-immigration trend and national retrenchment evident in some quarters suggests, a contest of paradigms is expected.

Both approaches are, however, interdependent. Micro histories provide the necessary intimate detail and abundant minutiae around which macro studies are crafted. Global forces or national policies do not, after all, derive their raison d’etre from, nor are economies driven by, petty imperatives. Labour strife is not exclusively the result of a narrow local vision. Wars are not fought, and lives are not lived, in truly isolated environs. In Fernie At War: 1914-1919, Wayne Norton interrogates these various tensions to make sense of the town of Fernie’s First World War experience.

Norton packs his narrative and analysis with the flotsam and jetsam of daily life, 1914-1919, and brings Fernie’s fractured and fissured history to light. It is a history well worth the attention. His main focus is Fernie’s response to a national war emergency, highlighted by patriotic expressions, sometimes rabid, and radical unionism. These themes are addressed in two ways, first by discussing expressions of martial fervour, especially community support for the flocking of young men to the service of king and empire.

Labour’s response to social and economic changes, by demanding the arrest and interment of enemy aliens in Fernie, thought by some to be self-serving racial antipathy, constitutes the second strand of the discussion. These responses, though seemingly disparate, were just two sides of the same coin. Canada’s war effort was characterized, as Norton recognizes, by the emotional force of extreme nationalism justified by crude propaganda that denigrated the enemy. Wars are driven by self-serving agendas. This is not a new debate, though centering Fernie in the broader context of a national war effort provides new details to the perspective.

It all began on June 5, 1915, when a small delegation of Belgian and English speaking miners at Coal Creek, near Fernie, acting independently of their union, voiced safety concerns about working underground with enemy aliens. By 8 June they had launched an illegal strike and ceased to work.

B.C. Attorney General, and later acting premier, William Bowser’s order for the internment of enemy aliens by 9 June, presaged four years of strife, pitting Fernie residents and returned soldiers against foreigners; union leaders against the rank and file; the Crow’s Nest Pass Coal Company (CNPCC) against the union; and eventually, union against union in the competition between the United Mine Workers of America and the One Big Union. And stirring this rather large cauldron of disaffection was the hand of Bower’s political ambitions. In short, Fernie’s became a local mess promising far-reaching repercussions.

Norton presents internment architect Bowser as ambitious and calculating, and it is difficult to disagree with this assessment. The internment policy was misguided, driven by Bowser’s self-serving agenda to court favour among Anglo voters. War, and the depressed economy, demanded scapegoats, found in the hundreds of foreign miners, especially Austro-Hungarians and Germans, inhabiting B.C.s mining communities.

Norton rightly places internee developments in Fernie in the broader provincial context. Bowser’s actions mirrored, in part, the federal government’s agenda embodied in the War Measures Act of 1914 by interning and deporting individuals deemed a threat to national security. Bowser correctly guessed that in a contest between a self-interested drive for inflated pay cheques by miners and union cohesion, the latter would be damned. Anglo workers, in league with other allied workers, such as Italians, defied their leadership, broke the bond of solidarity, and abandoned fellow unionists to their unhappy fate of internment.

Bowser’s crass appeal having worked, he then foisted the troublesome child he had spawned onto Robert Borden’s federal government. The federal government was driven to act by a looming court challenge that might well have determined that the arrest and detention of foreign residents was unlawful, resulting in their release.

The potential fallout for the national internment program was breathtaking and frightening. The government, in the interests of national security, acted with its Order-in-Council 1501, deferring the right of habeas corpus and legitimating the arrest of the internees at will. Thus, British Columbia’s foray into domestic national policy concerns became the source of much controversy, in Fernie and beyond. The disruption would remain for four long years. Of course, all such actions were deemed patriotically defensible.

This much-lauded prize patriotism was multi-layered and possessed inherent risks. Miners were enlisting at such rates that a labour pool shortage resulted, accompanied with dire warnings of possible mine shutdown, an unattractive local and national prospect.

A not unexpected response was the CNPCC’s request for the release of internees to remedy the labour shortfall, and those not considered a substantial risk eventually were. Continued labour shortages, however, drove the CNPCC to take the unprecedented further step of requesting a ban on local recruitment. Surprisingly, the federal ministry of labour concurred, and the federal government enacted Military Order No. 448. Norton asserts that this 1916 ban on local recruitment was the only measure of its kind in Canada. Only the local 107th East Kootenay Regiment was excluded from the ban.

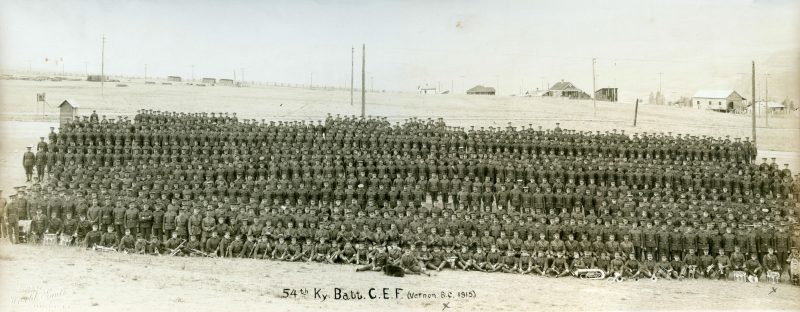

Cannon fodder: 54th Battalion at Vernon, 1915. Its B Company included men from Fernie. Harold Smith photo.

In the context of the national crises, when military manpower needs ran headlong into attempts by individuals and groups attempting to avoid military service, this unparalleled development in Fernie is significant indeed. It is a sterling example of how, without micro studies such as this one, the macro vision will never be complete.

An interesting aspect of Norton’s approach is his ambivalence regarding the extent to which Fernie and its history was, and is, neglected. Despite this, Norton convincingly demonstrates that Fernie was something more than tributary to events; and isolation, at whatever level, did not equate to neglect.

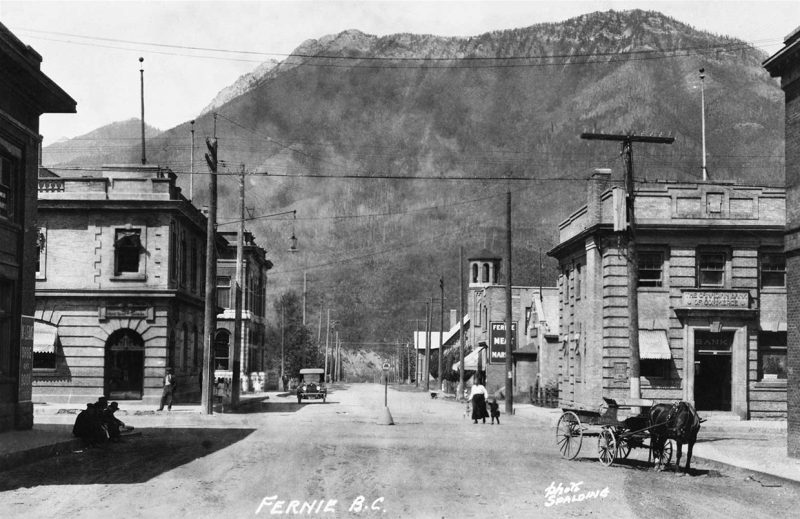

Fernie, for example, was a community served by two railways and a highway. The demands of the mining industry caused constant migration in response to the ebb and flow of labour needs. It was a town driven by, and responding to, local, national, and international pressures. The Crowsnest Pass spans the B.C. and Alberta border, towns on both sides being tied through a coal-based economy and international unionism, and these countered both isolating tendencies and historical neglect. Stressing Fernie’s isolation unfairly downplays both its interdependence and influence.

The abundant evidence Norton presents demonstrates that, by virtue of the significance of its economy and wartime disruptions around it, Fernie became both a national distraction and a disruptive force in international unionism spanning two provinces. Evidence of Fernie’s dual nature as both hinterland and metropolis is a major strength of Norton’s work. It was a complexity that he did not miss, but his work may have benefited from less subtle emphasis. This work, after all, is a significant contribution to contextualizing both a provincial and national perspective.

Norton’s discussions on prohibition may be the best illustration of the risks entailed in an attempt to sever a community from its broader geographical context for individualized study. Emilio Picariello, for example, conducted cross-border smuggling, a countervailing force to isolation. Because of individuals like Picariello, bootlegging that originated in Fernie was both commercially and legally entangled with Alberta or Montana. However, as Norton limits his discussion mostly to Fernie, the flourishing cross-border economic forces of prohibition are not fully revealed.

On a more technical note, there were a few editorial misses with this book. A perusal of my own library, for example, did not locate any book of this genre that placed the bibliography before the endnotes. There were also occasions when the names of newspapers were not italicized (p. 63). A more irritating flaw is the number of occasions where quoted, and otherwise specific, information is not accompanied by an endnote reference (such as the details on Emilio Picariello appearing on p. 101), a definite drawback for those wanting to access the wealth of detail that Norton has so generously offered. These are, however, irritants and not fundamental flaws.

The quantity and quality of Norton’s research, and the conclusions drawn therefrom, have resulted in a valuable study. And this work raises an important question, as good works of history should. Norton captured the significance of daily life in a small but rather complex community. Fernie’s history is specific, but is it unique in the general sense? What similarities and differences, for example, would a study of Hillcrest, Alberta, for this time reveal? How much influence or example did Fernie exert on Hillcrest?

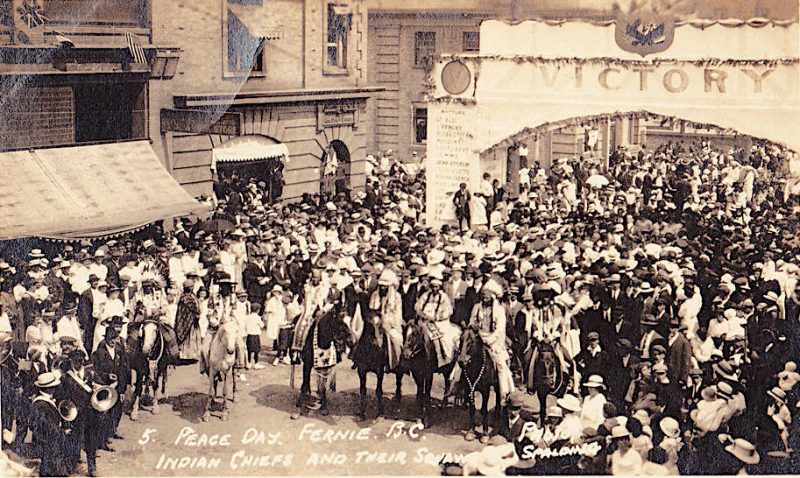

These questions aside, the historical issues discussed in Fernie At War: 1914-1919 are of such significance that this book desperately needed to be written. It is essential reading on the history of Fernie for both pundit and scholar and an especially timely reflective study of a local community at war from one hundred years on.

*

Keith Regular is a retired high school teacher and principal who lives with his wife Anne in Cranbrook. He began teaching in Newfoundland before moving to Elkford Secondary School, in Elkford, B.C., in 1986, and retired from there in 2014. Keith holds a Ph.D. from Memorial University of Newfoundland and is a specialist in southern Alberta Native and newcomer economic interaction at the turn of the twentieth century. His book Neighbours and Networks: The Blood Tribe in the Southern Alberta Economy, 1884-1939, was published by the University of Calgary Press in 2009. Keith has just completed a manuscript on the murder of Alberta Provincial Police constable Stephen Lawson in Coleman, Alberta, in 1922, and the subsequent hanging of his Italian immigrant killers after a trial that garnered national and international attention. He now has a manuscript in progress on the famed train robbery at Sentinel, Alberta, and subsequent shootout and killing of two police officers, at the Bellevue Café, Bellevue, Alberta, in August 1920. Keith enjoys researching Aboriginal history and the history of the Crowsnest Pass and Elk Valley areas of Alberta and B.

*

The Ormsby Review. More Readers. More Reviews. More Often.

Reviews Editor: Richard Mackie

Reviews Publisher: Alan Twigg — BC BookWorld / ABCBookWorld / BCBookLook / BC BookAwards / The Literary Map of B.C. / The Ormsby Revie

The Ormsby Review is a new journal for serious coverage of B.C. literature and other arts. It is hosted by Simon Fraser University. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Robin Fisher, Cole Harris, Wade Davis, Hugh Johnston, Patricia Roy, David Stouck, and Graeme Wynn.

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

My wife\’s maternal grandparents were emigrants from two of the coal geographies of the U.K., Wales and Yorkshire, and met and married in Fernie before the Great

War. He went overseas with the 54th. If there is a \”Ur\” settlement for emigrant/immigrant families, Fernie is hers, and our children\’s, and now their children\’s

Thanks to Wayne Norton for writing and Keith Regular for reading and reviewing.