Ted Hughes: Titan of Fairness

In 1993, Sun columnist Vaughn Palmer quipped, "Oh, mighty Hughes... we humbly beseech thee to forgive our sins.”

January 22nd, 2018

Saskatchewan-raised Ted Hughes has been a champion of decency and common sense since the 1960s.

Now Craig McInnes’s candid and engaging biography outlines the achievements of British Columbia’s most respected public servant.

The Mighty Hughes: From Prairie Lawyer to Western Canada’s Moral Compass

by Craig McInnes

Victoria: Heritage House, 2017.

$32.95 / 9781772032055

Reviewed by John McLaren

*

In Canada, biographies of appointed public servants are few and far between, compared with those of politicians. These days even judges are the focus of a larger output. Civil servants occasionally attract a biographer’s attention because they and their careers are mired in controversy. An example is Brian Titley’s penetrating work on the life and times of Duncan Campbell Scott, the administrator of “Indian policy” in Canada during its most aggressive period (A Narrow Vision, UBC Press 2007).

In Canada, biographies of appointed public servants are few and far between, compared with those of politicians. These days even judges are the focus of a larger output. Civil servants occasionally attract a biographer’s attention because they and their careers are mired in controversy. An example is Brian Titley’s penetrating work on the life and times of Duncan Campbell Scott, the administrator of “Indian policy” in Canada during its most aggressive period (A Narrow Vision, UBC Press 2007).

Public servants will sometimes try and prove the pundits wrong by publishing their own memoirs, such as the four volumes on the life and times of an energetic Federal mandarin and diplomat of the mid-twentieth century, Charles Ritchie (published by Macmillan, 1974-1983). Otherwise, the view seems to be that these characters are grey, even ghostly, figures whose lives were or are inherently uninteresting and thus unworthy of the biographer’s pen.

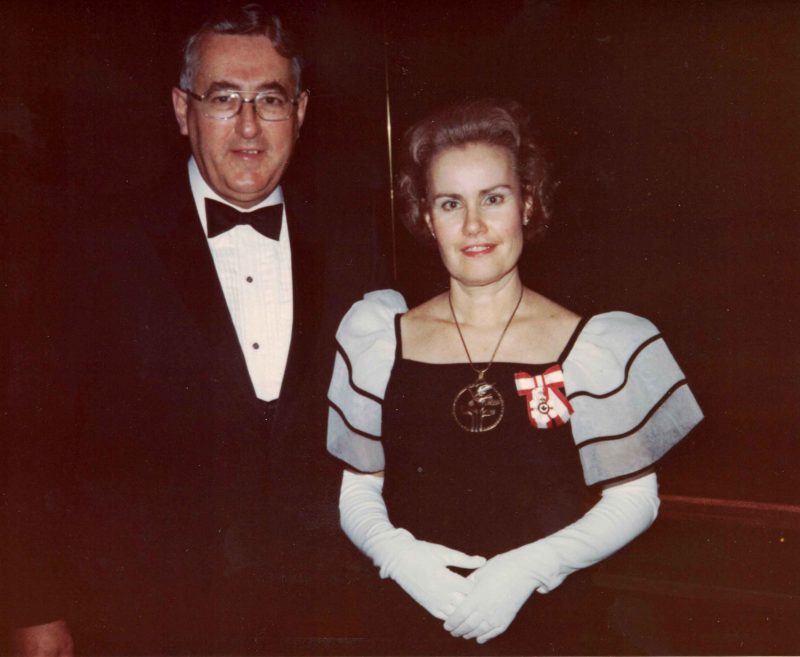

Happily, there are individuals who by dint of their stature, integrity, courage, and actions prove that life with them was neither anodyne nor routine, and whose careers have made a difference to Canada and Canadians. One such character is Ted (Edward Nelson) Hughes, the subject of Craig McInnes’s timely biography, The Mighty Hughes: From Prairie Lawyer to Western Canada’s Moral Compass. Full disclosure: my knowledge of and friendship with Ted and Helen Hughes dates back to 1964, a fact of which The Ormsby Review was unaware when they asked me to review this book. I am delighted to engage with this fine book about a remarkable man.

McInnes is a journalist of note, not an academic, and this book reflects that reality. It is a down-to-earth account of both a professional and personal life as lived, rather than a profound study of the philosophical, religious, and political wellsprings that the subject has drawn on in his life and career.

At the same time, it is well written and researched, and marked by an engaging narrative structured around a series of personal, legal, and political stories that demonstrate the contribution of an outstanding and fearless public servant who promoted high moral standards in government and true justice in the broader Canadian community.

Hughes is a man whose judgements politicians learned to respect and even fear, and who has been an exemplar of the values he advocates. The Mighty Hughes should be required reading for any young person contemplating a career in the public service and government, whether as a civil servant or politician, and even for those who have already embarked on such careers.

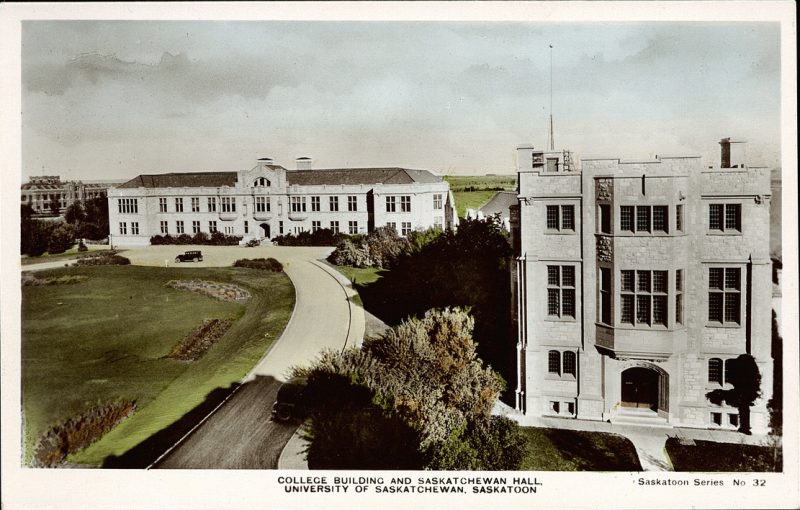

In the early part of the book, McInnes traces the immediate history of the Hughes family, stressing the supportive environment of a home in Depression-era Saskatoon, a solid Anglican upbringing, and the evident ability of the young Ted to focus on projects and to deliver on them successfully. This was as true of his newspaper delivery as a teen as it was of his high school and university commitment to debating.

The narrative accompanies him to the University of Saskatchewan first in Arts and then to the College of Law, where he benefitted from the encouragement and dedication of a flood of vets returning from the Second World War to complete their postsecondary studies. One small area of disappointment in the narrative during this period is the rather brief account of the legal education experience at the College during the late 1940s and early 1950s. As a legal historian, I wonder how Ted felt about the educational experience and the diminutive full-time faculty that managed and delivered it?

It was during his university years that Ted met his future wife and life’s soul mate, Helen. Hailing herself from a strong Anglican family with a commitment to service to the community, their marriage was from early days built on an ardent belief in the obligation of service to one’s neighbour. This was a far cry from a popular view of the era, embodied in 1965 in Pierre Berton’s characterization of “The Comfortable Pew” occupied by Canadian Anglicans who he branded as “the Tory party at prayer.”

Not that Ted Hughes would have eschewed a Tory identity. An enthusiastic young Progressive Conservative from his university days, he, however, espoused the populist brand of conservatism that had its roots in Saskatchewan and was associated with the political career of John Diefenbaker. As Ted muses in the book, the social credo he believed in was one that also took some inspiration from the social democratic (CCF) concern for equality and justice, similarly rooted in the politics of the province of his birth.

McInnes’s account of Ted’s early life in legal practice gives some hint of the long shadow that the Depression had in Saskatchewan. It is partly reflected in his experience as a greenhorn lawyer employed in North Battleford by a practitioner who not only ran a law office but owned a local funeral parlour, and took a telephone account of the newly deceased each morning. In time Ted became partner in the firm of Francis, Wood, Hughes and Gauley in Saskatoon, a firm that brought together a talented group of lawyers of different political persuasions.

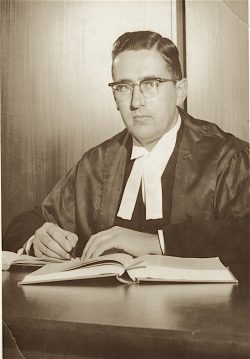

Ted made no secret of his Tory beliefs and connections. Propelled by a desire to move beyond a life of representing particular clients, he warmed to the idea of adjudication as a career objective. It was this that led him in the early 1960s to test his political connections about a judicial appointment. He candidly admits that in those days the process of judicial selection of a federally appointed judgeship was skewed by patronage, with political connections being a major consideration.

For him, the connection with the Diefenbaker government in Ottawa worked, and he was appointed to the Saskatchewan District Court in 1962 at the young age of 35. In due course, when that court was merged with the Court of Queen’s Bench, he became a justice of the latter court.

As a trial judge, McInnes reports, Ted covered a range of both criminal and civil cases, including the occasional high profile suit, such as part of the Colin and Joanne Thatcher divorce proceedings. More important is Ted’s reputation for listening carefully to the evidence, demonstrating respect for the parties, witnesses, and counsel, and weighing his decisions carefully while remaining firmly in command of proceedings — well, almost always.

A telling story in The Mighty Hughes, which introduced Ted to an aspect of Canadian life of which he knew little at the time, concerns an Indigenous defendant charged with and convicted of second-degree murder committed while he was seriously intoxicated. When invited to speak, he told the judge candidly that he had no respect for courts. “All courts are shit,” he uncharitably opined.

A situation that might well have been a cause for vigorous and adverse judicial reaction instead caused Judge Hughes to reflect on what might have been the source of the man’s opinions, and whether there were not, perhaps, elements of truth in what he was being unflatteringly and bluntly told.

The system of judicial appointments and advancement that was undergoing some tinkering by the Pierre Trudeau Liberals in the mid 1970s, at least to the point of producing lists of possible candidates and more departmental investigation — and occasionally, as in the case of Tom Berger, introducing a political outsider into the judiciary — was to backfire in Ted’s case.

Perhaps naively believing that he might be in the running for appointment as Chief Justice of the Saskatchewan Court of Queen’s Bench in the late 1970s (especially when interviewed by the Justice adviser on appointments), Ted felt that he had been shabbily treated when the appointment went to a former Liberal supporter, and he found himself the butt of gossip and criticism by most of his judicial colleagues. The climate was one that he describes as “poisonous.”

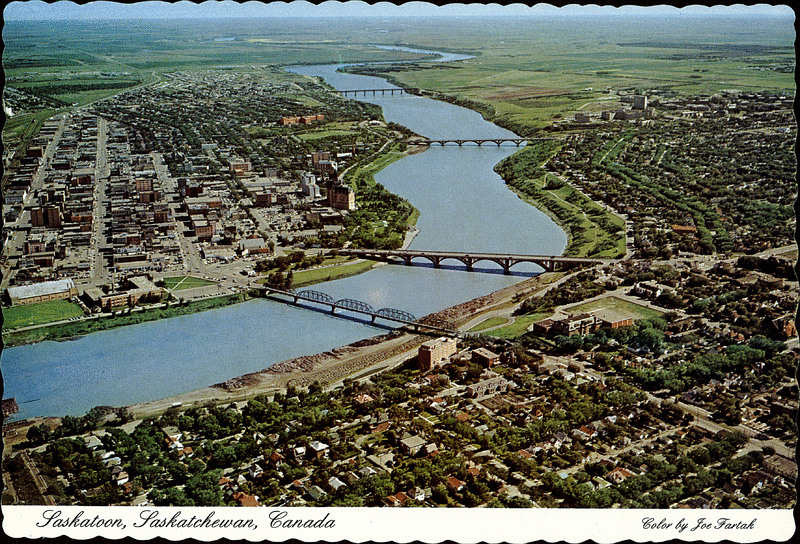

This led him to contemplate and to discuss with Helen resigning from the Bench and looking for employment elsewhere, preferably on the West Coast. This was not an easy decision for either of them, particularly as Helen, with Ted as her campaign manager, had in 1976 been elected a Saskatoon city councillor and, supported quietly by her husband, had begun to make an issue of the sometimes adverse treatment of First Nations residents within the city.

Outside the judiciary, Ted himself had taken a strong interest in the governance and services of the hospital system in Saskatchewan. Moreover, what would a former judge who eschewed private practice and was approaching what was then considered middle age find in the way of a living elsewhere?

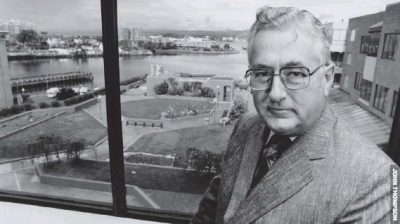

The two of them made the adventurous and fateful decision to move west. It is at this point in McInnes’s narrative that the pace quickens, a reflection in many ways of the turbulent politico-legal environment in B.C. and Ted’s various challenging roles and exploits within that setting. By threading together the episodes, crises and scandals that marked provincial politics, whether in the Socred or NDP years of the 80s and 90s to which he had to respond as Deputy Attorney-General, and as the first Conflict of Interests Commissioner, McInnes provides a lively and connected political history of the battle for morality and honesty in government in a jurisdiction with a long-standing reputation for zany and no-holds-barred politics.

In B.C., quickly rising from a journeyman government lawyer to Deputy Attorney General in 1983, Ted was to prove that one could loyally serve a government by applying professional talents to furthering its constitutional and legal agenda, while also supplying well-tempered and sometimes unwelcome advice when the government’s actions came close to or transgressed the bounds of law and morality.

Reflecting, too, his commitment to service beyond his day-to-day job, Ted picked up on his long-time interest in health care. Moreover, he earned a great deal of respect for the open-minded and candid reports that the task force and committee he led — respectively on access to justice and gender bias in the legal profession — rendered during the 1980s.

It was in his dealing with the largely untested and tricky issues of conflict of interest in government that Ted Hughes was to show his greatest mettle. His strong view was, and is, that governments and politicians need to act honestly, with integrity, and with respect for both the public interest and the rule of law. Anything less is to risk denigrating politics and political service.

However, this for him did not mean running off in a panic whenever the press or political opponents smelled “scandal.” In an era when there was no system for adjudging formally suspected conflicts of interest among politicians in B.C., McInnes describes how Ted, as Deputy A-G, quietly and professionally, and using the talents of people he worked with and respected, advised on several high profile cases involving ministers in the Social Credit governments of Bill Bennett and Bill Vander Zalm.

He did so with a keen eye to the circumstances and the evidence and always with a concern for balance and fairness. He quickly noted that there were instances in which, while a clear conflict could not be found, there was an appearance of conflict. This, he publicly reported, politicians ignored at their peril if proper ethical standards were to be observed and public trust ensured. Events came to a head during Vander Zalm’s tenure.

The premier had issued guidelines, rather than a legislated set of rules, as a mantra for his colleagues to observe. They included reference to appearances of conflict. Almost immediately, several of his ministers ran into trouble with conflict of interest charges. After careful investigation, Ted’s advice was not always to the satisfaction of everyone — for example of police convinced they had a case of corruption, and of opposition members baying for blood.

This was so in the tangled case of Bill Reid, the former minister of tourism, suspected of granting favours to political and personal friends, in which Ted advised against prosecution as having little chance of succeeding. This was a case that caused the Attorney General, Bud Smith, to resign for incautious comments in a recorded conversation about a lawyer proceeding on a private prosecution, and led to obstruction of justice charges by opposition member, Moe Sihota — who was then himself investigated with a view to his prosecution for wilful disclosure of a private communication.

It was, however, the Premier’s own activities that were to bring conflict of interest concerns to centre stage. As McInnes notes, Vander Zalm, who had already caused discomfort within his cabinet ranks with his attempts to intercede for a developer friend in the sale of Expo lands, was singularly unconcerned about his own activities breaching his own conflict of interest guidelines. This was especially so as they related to his desire to find a buyer for his theme park, Fantasy Gardens in Richmond.

When charges were levelled that Vander Zalm had used the Premier’s Office to facilitate a sale, Hughes, who had left his position as Deputy AG for something “less onerous” but was acting as Conflict Commissioner under legislation recently passed to establish that position, was asked by Vander Zalm to investigate the matter. When he did so, he discovered that secret payments to an agent for an offshore buyer had been made during a much-publicized visit by the purchaser, Tan Yu. Hughes concluded that there had been a serious breach of the conflict guidelines.

The Premier’s assumption that there was no conflict if the public did not know what was going on was entirely misplaced. This was made clear during Ted’s interview with realtor Faye Leung, who brokered the deal with Tan Yu. The natural, if dramatic, outcome was Vander Zalm’s resignation from office in October 1991. He immediately, ungraciously, and unsuccessfully sought judicial assistance in setting aside Ted’s report.

In the wake of these events, Ted was to be confirmed in the position of B.C.’s Conflict of Interest Commissioner with the support of both the Socreds and NDP. As McInnes puts it, “Hughes saw his role as restoring public faith in politicians by identifying ethical standards of behaviour and encouraging adherence to those standards.” By both his past actions and continuing activism in pressing this agenda when cases came before him that, in his opinion, involved departure from ethical norms, Hughes was to develop a reputation for setting a high bar for honest government in both B.C. and elsewhere in Canada.

His reputation was to induce the famed Vancouver Sun columnist, Vaughn Palmer, to quip in 1993, “Did you hear about the MLA’s prayer? ‘Oh, mighty Hughes, Maker of guidelines, giver of rulings, preserver of reputations, we humbly beseech thee to forgive our sins.’” While Ted no doubt chuckled inwardly at the reference, he would not have wanted to claim omniscience, let alone quasi-divinity. With an NDP government under Mike Harcourt now in power, he continued fearlessly to apply the principles of honest government in the cases that came to him from that quarter.

Characteristically, he acted with a lack of bias and openness in proceedings that — while his approach sometimes rankled those in power, including the Premier — provided no-nonsense direction on both the substance and formalities of ethical government. Relations between the NDP government and the Commissioner plummeted when the new Premier, Glen Clark, and his advisers — aware that Ted was coming to the end of his five year term and anxious to appoint someone who, in their minds, was more politically savvy and less demanding — sought to hasten his departure and replace him with David Mitchell, a former Liberal and then independent MLA.

Worn down by the machinations of the Premier’s office, Ted capitulated and cleaned out his office. After a conversation with Helen, they both agreed that what was at stake here was not Ted’s future (he was approaching three score years and ten), but the integrity of the office. In a press conference the next day he made it clear that he owed it to the office to reveal what had been going on in the corridors of power to hasten his replacement. In going public he was roundly supported by the Press. With a ritual wringing of hands and craven apologies from the Premier and his advisers, Ted was invited to resume office and remain until a successor was found.

When Ted left office in March 1997, at the age of seventy, one might have expected that a relaxed life of retirement lay before him. But, no! As McInnes deftly relates, Ted’s experience, zest for work, conscience — and the fact that Helen, with his support, had become an active and respected Councillor for the City of Victoria — suggested a third career for this energetic character. That roving career had begun already during the 1990s when Ted, whose appointment as Commissioner was not formally full time (or generously remunerated) was able and willing to take on other assignments. He embraced invitations to conduct one-off inquiries from other provinces and the Federal government.

Not surprisingly, given the mental jolt Ted had received years before in Saskatoon in sentencing the Indigenous accused, several of these inquiries provided him with experience in delving into the treatment of First Nations individuals and communities. One of these was a 1991 investigation of the conduct of the Winnipeg Police in seeking to tar the name and reputation of a Winnipeg lawyer, Harvey Pollock, who had criticized them roundly for their handling of the arrest and death of his client, an Indigenous man, J.J. Harper, in 1988. The outcome of the highly critical Hughes report in this instance was the immediate resignation of the Chief of Police. More importantly, it caused him to reflect that the police did not always serve and protect everyone in their communities equally.

An ostensibly non-Indigenous inquiry at the behest of the Government of Manitoba into the causes of a major riot at the Headingly Correctional Institute in April 1996 provided Hughes with insights into how one penal institution was run and how it impacted First Nations lives. He stressed, in a penetrating report, that he was not impressed with the selection or the training of line staff, nor with the apparent disinterest of senior correctional officials in conditions in the facility.

Noting that 70 percent of the inmates in that institution were Indigenous, as were 75 percent of gang members in the Province, he spoke out on the Indigenous dimensions of the issues before him. He pointed to the bankruptcy of policies that made little or no attempt to address the economic and social problems facing Indigenous Canadians and that helped explain the high number of First Nations people incarcerated.

The clarity and force of these two reports was not to be matched in the RCMP Complaints Inquiry into the use of violence by the Force against protesters of the APEC meeting in Vancouver in November 1997. McInnes describes the byzantine attempts to secure an RCMP Complaints Commission inquiry into those events following complaints by those on the receiving end of police action. This process was complicated by strong suspicions that the Office of the Prime Minister was implicated in directing police actions.

Hughes took over the enquiry and, with his characteristic vigour, conducted hearings and reviewed copious evidence. Although he heard evidence from an adviser to the Prime Minister, Jean Carle, he did not believe the terms of reference warranted him to issue a subpoena to Jean Chretien himself, and Chretien would not appear voluntarily.

The Hughes Report, while critical of the RCMP’s lack of planning for the event and of their tactical decisions made during the heat of the events, and of improper pressure by Carle, could not be definitive in terms of political interference, a serious disappointment to the more ardent protesters.

Next up was Ted Hughes’ important contribution to the Alternative Dispute Resolution (ADR) process, which he set up and ran between 2003 and 2007. The Chretien government had concluded that justice to residential school survivors (as well as the interests of the federal government and the churches that had run the schools) would not be well served by lengthy lawsuits that had been launched by several aggressive law firms on behalf of residential school survivors.

Despite the cavils of some counsel, Ted went about the organization of this initiative — leading, as always, by example — with an efficient structure and demonstrating humanity and respect towards both claimants and their culture and his own staff. In due course Ottawa was to revise the system of adjudication to expand its reach, as part of a broader settlement, including the establishment of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission. Those who McInnes consulted are firm in the conviction that the pattern and climate established by Ted Hughes continued to prevail in the adjudication process.

That age was not slowing Hughes down in terms of working in the public interest is evident in the fact that when recurring problems involving care and protection of vulnerable children and youth once again came into the spotlight in B.C. in 2006, it was Ted who was called upon to inquire into the issues. Pointing to the malaise of a ministry faced with financial cutbacks, a major crisis of confidence in staffing, and inability to provide effective service to its clients, he recommended the establishment of a Representative of Children and Youth, reporting to the legislature.

This advice was followed. It has meant the insertion of a person in the system empowered and ready to shine a light on the inadequacies of the system and to advocate tirelessly for change. That the problem of care of vulnerable children is not confirmed within specific geographic boundaries was once again highlighted in one of Ted’s last roving assignments, as head of an investigation into the tragic death of five year-old Phoenix Sinclair in Manitoba.

In an inquiry that focused on the risks to Indigenous children in child welfare systems, Ted, as he has always tried to do, made it abundantly clear that what was at stake was not only the failings of family members, but also the failure of the systems that were supposed to protect children, and a failure of officials and politicians whose responsibility was to ensure that the system had the resources and was operating effectively and humanely to meet the goals of care and protection.

Not for the first time, Ted draw attention to the sad history of the relations between settler Canadians and their governments and First Nations communities. On this occasion, he sought both through quiet pressure and advocacy in the Press to make this a public issue of the first magnitude.

One issue that McInnes meets head on in The Mighty Hughes is what some would see as an undue prickliness in Ted’s character — an apparent tendency to react negatively to personal criticism by one normally self-effacing and genial. This has been apparent in his relations with members of the press, such as Vaughn Palmer and the late Rafe Mair, and with politicians such as Jack Weisgerber, who cast doubt on his integrity and who were forced to issue apologies.

At a more public and dramatic level, Ted launched a successful defamation action against Bill Vander Zalm for a series of statements the latter made about Hughes in his biography written, McInnes suggests, as a means of settling old scores.

McInnes inclines to the view that Ted values as his trademark a commitment to the belief that public servants, whether elected or appointed, have a duty to act with honour and integrity. This stood him in good stead when he judged and commented on the conduct of others. I would go further and argue that Ted believes deeply that people — whether as a result of faith or humane instincts, or both, and honed by experience — owe to one another an obligation to respect each other, not to rush to negative judgement on each other’s deeds, views, and character without employing reason, supporting facts, and careful thought.

Ted believes that many others, similarly guided, might reflect on the harm they do with groundless charges, dismissive comments, and even ignorant, knee-jerk responses. In a world now tarnished by the wilful invention of “facts,” suffering the tweets and re-tweets of juvenile tantrums, and witnessing character assassination at the highest political levels, this demanding aspiration has much to commend it.

Needless, to say, a review can only capture some of the highlights of a 320-page biography. There is much more in this book, not least the sterling work of Helen Hughes, as always supported by Ted, as a determined advocate in municipal politics for the underdog, first in Saskatoon and then for many years in Victoria, as well as their support for their family in joy and in sorrow, for their quiet encouragement of their faith community in its outreach and social justice work, and for embodying in so many ways the values of a “civil society” at its very best.

It was a particularly joyous occasion when both Ted and Helen were recognized in 2005 by the University of Victoria as honorary LL.D. recipients at the same Convocation. I was honoured to write the citation for Ted in which I quoted from one of his colleagues at the Attorney-General’s Department:

One of the reasons he has been so successful … is that he wrestles with the moral, ethical, legal, and above all, personal dimensions of the problem at hand in order to come to a fair and just conclusion. In all of his undertakings, he has given the public confidence that any matter he undertook would be handled with thoroughness and honesty.

This encapsulates perfectly the contribution to the public welfare of Canada of this remarkable individual and succinctly sums up the underlying message of Craig McInnes’s readable, candid, and engaging biography.

*

Educated at the universities of St. Andrews and London, John McLaren taught law in Saskatchewan, Ontario, and Alberta before moving to the University of Victoria in 1987. He has been a Visiting Fellow at Cambridge University and at the Australian National University. His major areas of interest are Canadian and colonial legal history, legal education, legal theory, and compensation law. Among his books are Law for the Elephant, Law for the Beaver: Essays in the Legal History of the North American West and Essays in the History of Canadian Law (Canadian Plains Research Centre, 1992, edited with Hamar Foster) and Land and Freedom: Law, Property Rights and the British Diaspora (Routledge: 2001, edited with Andrew Buck and Nancy Wright). John served on the Canadian Human Rights Tribunal, was a founder of the Canadian Law and Society Association, has been involved in reform work on the civil law relating to sexual assault, is active in refugee work, dances the Morris, and lives in Victoria.

*

The Ormsby Review. More Readers. More Reviews. More Often.

Reviews Editor: Richard Mackie

Reviews Publisher: Alan Twigg — BC BookWorld / ABCBookWorld / BCBookLook / BC BookAwards / The Literary Map of B.C. / The Ormsby Revie

The Ormsby Review is a new journal for serious coverage of B.C. literature and other arts. It is hosted by Simon Fraser University. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Robin Fisher, Cole Harris, Wade Davis, Hugh Johnston, Patricia Roy, David Stouck, and Graeme Wynn.

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

Leave a Reply