#348 The ghost of Jack Munro

August 22nd, 2018

On the Line: A History of the British Columbia Labour Movement

by Rod Mickleburgh

Madeira Park: Harbour Publishing, 2018.

$44.95 / 97871550178265

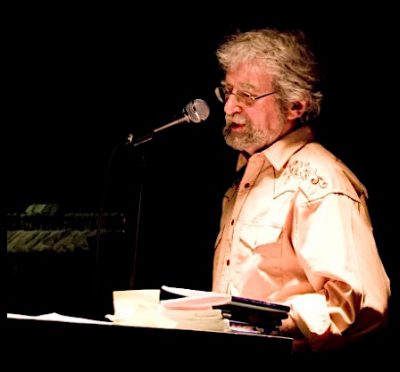

Reviewed by Bryan D. Palmer

*

For four tumultuous months in 1983, the grassroots labour initiative in B.C. called the Solidarity Coalition–which took its name as an offshoot of the successful Solidarity movement in the shipyards of Poland at the time–was fighting the Social Credit government’s Restraint Budget.

For four tumultuous months in 1983, the grassroots labour initiative in B.C. called the Solidarity Coalition–which took its name as an offshoot of the successful Solidarity movement in the shipyards of Poland at the time–was fighting the Social Credit government’s Restraint Budget.

Finally, on November 13, Jack Munro, president of the International Woodworkers of America (IWA), signed a controversial deal with B.C. Premier Bill Bennett to end the Coalition’s plans for a general strike.

Rod Mickleburgh’s On the Line: A History of the British Columbia Labour Movement revisits that struggle, along with countless others, to celebrate — according to the publisher’s blurb — the role of unions in establishing “the five-day work week, the eight-hour day, paid holidays, the right to a safe, non-discriminatory workplace and many more taken-for-granted features of the modern work landscape.”

Labour historian Bryan Palmer, as the author of his own book on B.C.’s Solidarity Crisis of 1983, now offers his critical take on Mickleburgh’s impressive overview. — Ed.

*

It has been more than fifty years since British Columbia’s workers have been treated to a broad, synthetic coverage of their own history. The narrative of brutal class conflict, heroic struggles to secure trade union rights, workplace dangers and deaths, political activism, and the splitting apart and coming together of a workforce divided from its first stirrings by race, ethnicity, and gender rivals that of any other region of Canada in dynamism and drama.

The last attempt to provide a full history of B.C. labour, Paul Phillips’ No Power Greater: A Century of Labour in British Columbia (1967), was written by a research director of the British Columbia Federation of Labour [ B.C. Fed]. Phillips would later go on to be a distinguished political economist and central figure in Canada’s most left-wing Economics Department at the University of Manitoba.

The last attempt to provide a full history of B.C. labour, Paul Phillips’ No Power Greater: A Century of Labour in British Columbia (1967), was written by a research director of the British Columbia Federation of Labour [ B.C. Fed]. Phillips would later go on to be a distinguished political economist and central figure in Canada’s most left-wing Economics Department at the University of Manitoba.

No Power Greater was a gritty $1.50 paperback. Its photographs and illustrations were grainy, and the publications on the province’s workers that it could draw on slim to almost none, Phillips relying largely on his own unpublished doctoral thesis and the original sources he mined to write it, as well as research by solitary scholars such as Keith Ralston. This pioneering work was undoubtedly produced on a fiscal shoestring. Support was provided by the B.C. Fed and the Boag Foundation, but the research and writing was conducted by Phillips. Phillips’ book established how workers in British Columbia struggled to create unions and intervene in the political life of the province in ways that would lift “labour from a dispensable tool of production to the level of human beings.”[1]

This seemingly echoes the purpose of the man who looms behind the production of Rod Mickleburgh’s new history of British Columbia labour, Jack Munro, whose purpose in life, it has been claimed, was to make unions a respectable part of society. When Phillips used the language of “tool of production,” however, he was in actuality gesturing towards an understanding of class as a structured presence in a system of capitalist exploitation that is at odds with Munro’s sensibilities.

Indeed, one measure of the gulf separating the No Power Greater of the 1960s and Rod Mickleburgh’s On the Line of 2018 is the sense of unambiguous struggle and active intervention conveyed in the title of the earlier study, which draws on the Pete Seeger rendition of a powerful labour anthem, “Solidarity Forever.” This contrasts with the seemingly ambivalent juxtaposition of passive acquiescence (existing in workplaces/keeping up with the production schedule) and the fight that inevitably arises out of contrasting class interests conveyed in the naming of On the Line.

Another reflection of difference is that while Phillips described a century of working life in B.C., he was also always at pains to explain the unique political economy of the region, how it ordered class relations in particular ways, and the extent to which the deep structures of everyday life were conditioned by capitalist development and the peculiarities of the labour market in a resource extractive economy. These included the skewed power imbalance of the region’s material life, in which commercial empires and concentrated ownership and control of the levers of accumulation pitted workers against monopolies that Gustavus Myers described in his 1914 study of the first Canadian fortunes.[2]

Economic dominance translated seamlessly in early British Columbia into the fused interests of “development,” governance, and state power. In turn, this insured that struggles for better wages and conditions would be hard fought and stamp the formation of the labour movement in British Columbia with a degree of class struggle militancy and organized political opposition that was often the vanguard of a wider, pan-Canadian trade unionism.

Phillips thus explored how the oscillations in the business cycle inevitably challenged workers with debilitating periods of crisis; he wrestled, persistently, with the need to interpret what was unique about the west coast labour movement. In this analytic narrative, the province’s workers are always presented as beset with a number of often conflictual components of mobilizations (craft versus industrial unions; Industrial Workers of the World/One Big Union syndicalists versus Communists versus social democrats in the Co-operative Commonwealth Federation, etc.) that were nonetheless all forged in the formative crucible of the symbiotic relationship of socialism and the early trade unions. Not surprisingly, Phillips ended his short, 165-page book with an interpretation of B.C. labour that accented how ongoing capitalist development was, in spite of its capacity to erode solidarity and condition acquiescence, creating new conditions for “another surge in the labour movement.”[3]

On the Line is an entirely different kind of book. At $44.95 you get what you pay for. Lavishly illustrated, beautifully designed, and drawing on a library of scholarly monographs and academic articles, the coffee-table style book is an aesthetic accomplishment that lacks the explanatory verve of Phillips’ earlier study. Written with panache by labour journalist Rod Mickleburgh, the book describes but makes no pretense to analysis. It would be a mistake, however, to read On the Line as an objective, factual narrative, devoid of interpretation. On the contrary an unstated orientation animates this account. The presentation is crisp and fast-flowing, to be sure, and the illustrations punctuate the stories with evocative representations of a rich past. B.C. labour clearly has a long history of fighting for its rights. That said, Mickleburgh’s account regularly suggests that such struggles should be waged in specific ways and led by particular kinds of people.

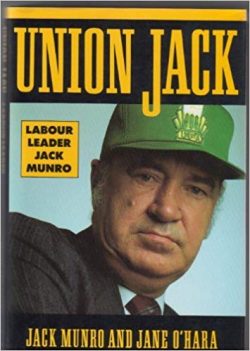

The beginnings of On the Line lay in the commitments to labour heritage of International Woodworkers of America (IWA) long-time leader, Jack Munro. After leaving the IWA in 1992, his tenure there totaling 33 years, Munro took up a sinecure with the Forest Alliance of B.C., a corporate-funded public relations outfit founded to counter the environmental lobby and defend the interests of the lumber barons as well, supposedly, as their waged employees.

Munro devoted his last years to chairing the British Columbia Labour Heritage Centre, floating the idea of an updated history of workers and their movement in the summer of 2013 at the same time that his health was deteriorating rapidly. Within months of its informal inauguration, the B.C. Labour History Book Project had the support and participation of the B.C. Federation of Labour and the Simon Fraser Labour Studies Program, seed money provided by WorkSafeBC.

This hopeful marriage of the labour movement’s officialdom and academics involved in researching and writing working-class history and mounting classes and conceptualizations of labour studies did not take long to exhibit signs of strain. An inside history of the unravelling of this partnership, revealing how different the perspectives of the trade union tops and the intelligentsia they wanted to draw upon but always keep in check, would provide a fascinating glimpse into one dimension of the politics of contemporary trade unionism and the sociology of knowledge.

Comparing this tension to what might be discovered about Paul Phillips’ working relationship with the B.C. Fed leadership of the 1960s would also prove instructive. Reading between the lines of these two texts, one suspects the labour leadership of the mid-1960s was more comfortable giving a young scholar and researcher in their employ some leeway to pursue history where evidence took him than their later-day equivalents, who may well have wanted an end product more in line with their way of thinking.

This kind of speculation — and without access to a fuller record of the relations of trade union officials, academics, and the writing of On the Line any comment is little more than conjecture, however suggestive — is necessary because the closer Rod Mickleburgh’s history edges toward the present, the more there appears to be an effort to represent working-class struggles, their outcomes, and their meanings, in particular ways. There is no denying that the decisive event in structuring how working-class struggle in the modern period is depicted in On the Line is the 1983 upheaval known as Solidarity. As an experience of opposition to the politics of restraint and austerity, in which trade union leaderships, rank-and-file militancy, and social activist mobilization played particular roles, Solidarity was a formative moment in the making of British Columbia labour history.

Given that the same trade union figure, Jack Munro, who championed the making of On the Line was the same private sector labour movement leader who proudly occupied centre stage in the termination of Solidarity, it is undeniable that the ghost of Jack Munro haunts this successor to Phillips’ No Power Greater. Few B.C. labour figures could possibly have exercised the same kind of impact on a B.C. Fed-sponsored publication in the 1960s. When Jack Munro died in the fall of 2013, the IWA-founded Community Savings Credit Union ponied-up an amazing $200,000+ to financially partner in the creation of what was understood to be a book honouring “Union Jack.” On the Line is “respectfully dedicated to Jack Munro” (pp. v, xi). The resulting history, then, will undoubtedly play to mixed reviews, for Munro was not the kind of figure to build consensus. He polarized, as will a history written to validate his legacy.

Mickleburgh, the recipient of labour research provided by scholars who signed on to the book project in its earliest stages (some of them economically precarious graduate students) and the beneficiary of a number of relatively-recent and deeply researched publications on subjects such as miners, dock labour, fisher folk, and First Nations involvement in B.C.’s unions and resource-extraction work, is not always fulsome in his acknowledgement of what he has drawn upon.

For example, the accent in early chapters on the important role Indigenous peoples played in the west coast region’s early working class draws heavily on the pioneering 1978 study of Rolf Knight, reissued in 1996, Indians at Work: An Informal History of Native Labour in British Columbia, 1858-1930 (New Star Books), as well as on more recent historical studies such as John Lutz’s Makuk: A New History of Aboriginal White Relations (UBC Press, 2008). These works are at least cited in the bibliography, but Andrew Parnaby’s Citizen Docker: Making a New Deal on the Vancouver Waterfront, 1919-1939 (University of Toronto Press, 2008) goes unmentioned. It presents the fullest account of Squamish waterfront work and the Industrial Workers of the World Local 526, known as the “Bows and Arrows,” so important in the history of early twentieth-century longshoremen’s lumber loading in Vancouver.

For example, the accent in early chapters on the important role Indigenous peoples played in the west coast region’s early working class draws heavily on the pioneering 1978 study of Rolf Knight, reissued in 1996, Indians at Work: An Informal History of Native Labour in British Columbia, 1858-1930 (New Star Books), as well as on more recent historical studies such as John Lutz’s Makuk: A New History of Aboriginal White Relations (UBC Press, 2008). These works are at least cited in the bibliography, but Andrew Parnaby’s Citizen Docker: Making a New Deal on the Vancouver Waterfront, 1919-1939 (University of Toronto Press, 2008) goes unmentioned. It presents the fullest account of Squamish waterfront work and the Industrial Workers of the World Local 526, known as the “Bows and Arrows,” so important in the history of early twentieth-century longshoremen’s lumber loading in Vancouver.

Mickleburgh summarizes, in ways that would have been unimaginable in the 1960s when Phillips produced No Power Greater, how British Columbia’s diverse First Nations contributed to waged work in nineteenth and early-twentieth century logging, sawmilling, mining, longshoring, farming, and fishing. He does little to explore or explain the complex ways in which Indigenous peoples negotiated wage labour and their customary economies of subsistence, adapting to specific work sectors that could accommodate the rhythms of seasonality by which the casualism of certain paid occupations in the capitalist marketplace could co-exist with traditional regimes of hunting, fishing, and harvesting the bounties of nature. Little time is spent addressing how a political economy of capitalist colonialism was established on the west coast, often through the use of violence. Had this issue been addressed more frontally the ways in which First Nations were separated from their traditional lands and livelihoods would have provided an extremely useful contextualization of class formation in British Columbia.

“Racism infected white settler society.” Indigenous lumber handlers, along with some Chileans and Hawaiians, gather near the Moodyville Sawmill on the north shore of Burrard Inlet in 1889. The man with the laundry bag is William Nahanee; he worked many years on the docks, serving as president of the groundbreaking Bows and Arrows union local formed in 1906. Fifth from the left is Joe Capilano, later a prominent chief of the Squamish. Charles S. Bailey photo, City of Vancouver Archives

If a little more time had been spent on this important aspect of the origins and nature of colonial capitalism, a decisive sensibility could have been cultivated: how the dispossession of Indigenous peoples proceeded in ways that consolidated a white settler society that was itself always premised on an ongoing dispossession of the working class, which now had its First Nations, settler, and (further complicating the narrative) immigrant components, some of the latter being Asian. Racism infected white settler society. This pernicious reality was fomented at least in part by state policies that socially constructed First Nations in particular ways and conditioned, again in part, their relationship to waged work and settlers of various kinds. It translated usefully into the brutalizing and super-exploited gang labour of the Chinese in dangerous mine and railway construction work.

All of this is described well enough by Mickleburgh. But an opportunity is missed to explain just how this racism worked in segmenting the British Columbia labour market and dividing potential allies whose experiences of exploitation at the hands of those who occupied the pinnacles of state and business power in the west coast province extracted their ill-gotten gains from First Nations, white working-class settlers, and Chinese labourers alike. As the B.C. Federationist declared in 1914: “The organized labor movement is opposed to Asiatic immigration because Asiatic labor is cheap labor. It is not essentially a question of whence it comes or what its name or color is. The point is that it is cheap, and as such is a menace to the wages and standard of living which the organized white workers are spending money and effort to try to maintain.”[4]

The problem, of course, is that in defending wage rates, the workers’ movement — which included unions as well as left-wing organizations — tended to rally around the white wage. Organized labour tended to be white; immigrant peoples of colour, most emphatically Asians on the west coast, were likely to be excluded from the collective workers’ experience that mounted resistance to capital and claimed pride of place in the class struggle.

The racism that thus manifested itself within work relations in the mining, fishing and other employment sectors, as well as in early mobilizations of workers in organizations like the Knights of Labor of the 1880s and the trade unions of the World War I era, structures Mickleburgh’s early narrative of B.C. workers. As a consequence we see too little of the reciprocal experiences of Chinese men and aboriginal women, less expensive than male workers, who sustained the lucrative profits in early canneries, where, as Mickleburgh recognizes, they were regarded as the “steam engines” that drove profits to new heights. (p. 22).

The conventional wisdom that Chinese strikebreaking in the mining strikes of the 1860s and 1870s fanned the flames of white miner racism is not entirely wrong, but Mickleburgh perhaps misses an opportunity to discuss how, in the earliest miners’ strike, relations and job actions on the part of white and Chinese miners were more complicated. He skirts entirely fascinating recent evidence of how, marginalized in the march of capitalist progress, Chinese immigrants and the Sto:lo forged a unique bond on the banks of the Fraser River, intermarrying and integrating their ways.

The Sto:lo people, aware that scores of Chinese labourers had been ploughed into mass graves when killed on their dangerous railway-construction jobs or decimated by flu epidemics, apparently welcomed survivors into their midst and, in turn, these Asian newcomers influenced the evolving architecture of the Sto:lo, construction of their dwellings taking on the appearance of ancient Chinese dwellings. Archaeological excavations of Sto:lo village sites have turned up Chinese coins dating to the 16th century.[5]

What Mickleburgh has done, then, is describe but fail to probe more deeply, and in the process he reproduces common-sense understandings. Sometimes these are relatively benign, as when he comments on a piece of miner’s memorabilia, noting that, “So common were mine fatalities that the reverse side of early mine union ribbons was black, so they could easily be turned into ribbons of mourning” (p. 17). This sounds plausible, but the actuality is that every nineteenth-early-twentieth century trade union/fraternal society ribbon had a black reverse, to be pinned and worn at the funeral of a brother, regardless of whether his death occurred on the job or not. Moulders, street railway employees, carpenters and joiners, as well as Oddfellows or Orangemen, wore ribbons with this black “In Memorium” reverse side. Not knowing this component of labour’s experience suggests how distanced Mickleburgh is from a body of recent history that has detailed aspects of working-class culture.

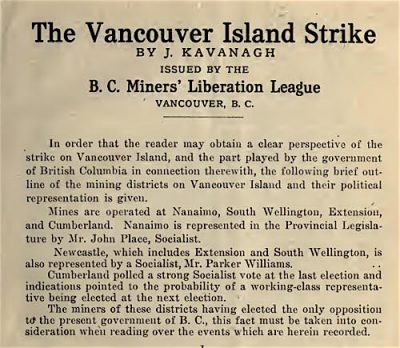

Mickleburgh is less interested in this kind of social history than he is in recounting overt class struggle. Militant unions like the Western Federation of Miners and its related movement, the Industrial Workers of the World, were, by the opening decades of the twentieth century, the reflection of an escalating conflict pitting workers against powerful employers; miners and immigrant railway-building labour were increasingly important. Campaigns for the shorter, eight-hour, workday mushroomed; free-speech fights in Vancouver challenged law-and-order attempts to muzzle public criticism of an iniquitous capitalist system; strikes increased both in number and in violence, and included a confrontation memorialized as the Great Vancouver Island coal strike of 1912-1914, a protracted 23-month struggle that gave rise to the Miners’ Liberation League. It is in exploring and explaining the militancy of these struggles that the relationship of revolutionaries within the workers’ movement and the making of British Columbia trade unionism intersects.

Mickleburgh is less interested in this kind of social history than he is in recounting overt class struggle. Militant unions like the Western Federation of Miners and its related movement, the Industrial Workers of the World, were, by the opening decades of the twentieth century, the reflection of an escalating conflict pitting workers against powerful employers; miners and immigrant railway-building labour were increasingly important. Campaigns for the shorter, eight-hour, workday mushroomed; free-speech fights in Vancouver challenged law-and-order attempts to muzzle public criticism of an iniquitous capitalist system; strikes increased both in number and in violence, and included a confrontation memorialized as the Great Vancouver Island coal strike of 1912-1914, a protracted 23-month struggle that gave rise to the Miners’ Liberation League. It is in exploring and explaining the militancy of these struggles that the relationship of revolutionaries within the workers’ movement and the making of British Columbia trade unionism intersects.

Revolutionary socialism and a more moderate labourite politics competed for the hearts and minds of the workers in the political arena. Elected representatives of the workers catch Mickleburgh’s attention, and their radicalism tends to be understated. Men such as James W. Hawthornthwaite, who sat in the provincial legislature from 1901-1912 and 1918-1920, sponsoring Canada’s first Workmen’s Compensation Act in 1902, figure in On the Line, but his Socialist Party of Canada membership, and its meaning, is made far less of than his capacity to win a legislative seat. To be sure, Hawthornthwaite let no opportunity pass that might see reforms of an ameliorative nature and of benefit to the working class be passed. But he was no less an advocate, ultimately, of a radical, root-and-branch transformation of the social order for all of that. He used the hustings to educate workers in the need to fight relentlessly against the capitalist interests, and the miners of Nanaimo who backed him would do so, in the view of the Socialist Party of Canada, “till the revolution.”[6]

A leading revolutionary Marxist of the time, E.T. Kingsley, enticed to Nanaimo from the United States by miners who formed the short-lived Revolutionary Socialist Party of British Columbia, merits no mention in this book. The double-amputee, who lost his legs in an industrial accident, spent his hospital-recovery time reading Marx, and was a relentless critic, not only of capitalism but of the acceptance of its exploitative and debilitating conditions by the “wage slaves.”

Brought to Vancouver Island to insure that the revolutionary movement made no concessions to reformism, Kingsley espoused a politics of “uncompromising political warfare against the capitalist class, with no quarter and no surrender.” By 1910 he was, arguably, the most important and knowledgeable Marxist theoretician in the country. Kingsley edited the socialist newspaper, the Western Clarion, and many in the small, but influential, ranks of revolutionary socialism, not only in B.C., but across the country, learned their Marxism from the west coast propagandist they referred to affectionately as “the Old Man.”[7]

B.C.’s demographic make-up, in which racial difference structured work relations and at times deepened solidarities against employers at the same time as it could fracture stands of collective resistance, has always been a unique cauldron of class formation. Native peoples constituted the majority of the province’s population until 1891, while white settlers often worked in proximity to a significant Asian population. The consequences of this racialized order were evident in a 1901 strike involving First Nations, white settler, and Japanese (Nikkei) components of the Grand Lodge of B.C. Fishermen. All were members of the nascent multi-racial union, but each constituency, in an age predating formal, state-sanctioned collective bargaining, could negotiate separate arrangements with the canneries that bought their harvests of seas and rivers. As the Nikkei settled first, white and Indigenous strikers battled armed patrols protecting the Japanese fishing boats. When the opportunity presented itself, the Nikkei boats were boarded by angry strikers, fishing nets were cut, the Japanese fishermen returned to land, their boats set adrift. On one occasion a dozen Nikkei were marooned on Bowen Island. A white union leader brought to trial for kidnapping and a weapons charge was exonerated in the courts, the Crown lawyer complaining that it was impossible to convict the culprit in “the union town” of Vancouver. In the years to come racial divisions in the fishing industry would plague struggles of the workers against the fish companies, with First Nations fishers taking militant stands that were undermined by white fishermen, and Nikkei strikes broken when Indigenous and white settler fishers accepted company offers the Japanese refused.

Mickleburgh details many events of this nature in a readable, accessible account that brings to life the volatile class relations of British Columbia’s growing and complex economy. He also introduces women and their relationship to the labour movement, outlining the important role of Women’s Auxiliaries in the male-dominated unionism of the resource communities of Vancouver Island and the interior as well as exploring women’s work and its discontents in female work sectors like switchboard operators at BC Tel. Figures such as Helena Gutteridge, a socialist, suffrage advocate, and city councilor in Vancouver, worked tirelessly in the World War I era to organize women workers in employments such as sewing and laundering.

As much of this history suggests, B.C.’s early trade unionism was not really separable from the socialist movement that grew alongside of it. During the World War I era, when labour radicals such as British Columbia Federation of Labour spokesman and Socialist Party of Canada member, Ginger Goodwin, resisted conscription and paid for his defiance with his life, shot by a special constable near Cumberland, trade unions in Vancouver rallied with a one-day General Strike. The red flag was draped over podiums at labour halls and the increasingly radical B.C. Federation of Labour advocated One Big Union of all workers, eschewing the racial exclusion that had divided the workforce for generations, albeit never as totally and as decisively as the conventional wisdom too often reproduced in Mickleburgh’s history suggests.

As much of this history suggests, B.C.’s early trade unionism was not really separable from the socialist movement that grew alongside of it. During the World War I era, when labour radicals such as British Columbia Federation of Labour spokesman and Socialist Party of Canada member, Ginger Goodwin, resisted conscription and paid for his defiance with his life, shot by a special constable near Cumberland, trade unions in Vancouver rallied with a one-day General Strike. The red flag was draped over podiums at labour halls and the increasingly radical B.C. Federation of Labour advocated One Big Union of all workers, eschewing the racial exclusion that had divided the workforce for generations, albeit never as totally and as decisively as the conventional wisdom too often reproduced in Mickleburgh’s history suggests.

Indeed, at times it seems as if Mickleburgh wants to present “labour’s onging campaign against Asian immigrants, a campaign that commonly included overt racism,” as the responsibility, entirely, of the working class and its revolutionary advocates in bodies like the Socialist Party of Canada [SPC] (p. 31). Exempting labour and socialists from criticism relating to the obvious racism directed against the Chinese and Japanese in British Columbia, especially from the 1870s into the 1920s, would of course defy much historical evidence and excuse what should never be sidelined. But any serious consideration of racism from below, addressing the extent to which working-class people articulated and lived their racism, demands, as well, a serious scrutiny of how that racism was conditioned in the cauldron of a racialized capitalist order. State policies, employer actions, and the hegemonic structures of early B.C. society facilitated the development of working-class racism and divided workers against one another the better to feed the appetite for profit.

The complexities of the situation demand that if the SPC’s political immigration plank of Asian exclusion is singled out for critique, as it is by Mickleburgh, it should also be recognized that this very same Socialist Party of Canada could also take strong and unpopular stands defending ostracized Asian immigrants. When 376 South Asian passengers on board the Komagata Maru were stranded in Vancouver, refused entry to Canada by the state, and then, two months later, escorted out to sea by a Canadian warship, it was the SPC that took a stand against the racism that ran rampant throughout society against the South Asians, building a fragile, if unprecedented, Socialist-Sikh alliance.[8] With the arrival of a Communist Party on the scene in the 1920s, displacing the Socialist Party of Canada, this politics of solidarity took hold of more and more of British Columbia’s workers.

Communists, their political allegiance to the Russian Revolution of 1917 sealed in a commitment to production for use rather than profit, were pacesetters in organizing the unorganized by the time of the Great Depression of 1930s. One of their number, Slim Evans, latched on to a rank-and-file suggestion to extend the protests of the jobless, organized by the Relief Camp Workers Union in the spring of 1935, into a trek to Ottawa, where the out-of-work could confront Prime Minister R.B. Bennett. The 3,000-mile jaunt was, in Mickleburgh’s word, “mad.” The Communist Party with which Evans was affiliated thought so as well, but it had been outflanked by its organizer’s audacity, which captured the enthusiasm of the increasingly frustrated single men who were forced to endure drudgery and intolerable conditions in the militarily-run relief camps, their meaningless work compensated by a meagre twenty cents a day.

As the trek stalled in Regina, with Evans and a few others offered a train trip to Ottawa to meet with Bennett, who insulted them and precipitated a walkout, the Royal Canadian Mounted Police moved to break-up the protest on 1 July 1935. A deadly riot ensued. Three years later, another Communist, Steve Brodie, led the Vancouver unemployed in occupying the Post Office building, their forced exodus an orgy of police violence that left 38 protesters hospitalized and dozens more injured.

There were other battles royal in British Columbia, including a violent 1931 strike at the ethnically diverse Western Canadian Lumber’s Fraser Mills, where the Communist-led Workers Unity League (WUL) resisted the imposition of a fifth wage cut in less than two years. It also refused the inclination to scapegoat non-white workers as enemies of higher wages and collective improvement of conditions. When the notorious Reds infiltrated the Vancouver and District Waterfront Workers Association, a company union established in the aftermath of a 1923 routing of the International Longshoremen’s Association by the employer’s Shipping Federation, WUL militants galvanized a showdown that culminated in a five-month strike and a brutal, one-sided battle at Ballantyne Pier. This memorable clash pitted dockworkers against three layers of police — municipal, provincial, RCMP — who were liberal in their use of tear gas and truncheons.

Communists also figured prominently in the industrial union organizing drives of the 1940s, especially among IWA loggers, who struck in 1943, and in the Traill operations of the Consolidated Mining and Smelting Company, where workers secured a first collective agreement in 1944. A catalogue of confrontation tends to substitute, in Mickleburgh’s account, for a history of working people that addresses the changing nature of families, neighborhoods, and leisure activities, as well as the restructuring of workplaces and the nature of technologies that periodically revamp labour processes, all of which would help shift the nature of working-class life, bringing the forward march of trade unions, if not to a halt, at least to a different pace.

Mickleburgh’s account leaves no doubt that much of the militancy and industrial union organizing of the 1930s and 1940s was due to the Communist Party’s (CP) de facto leadership of workers’ mobilizations. Yet it was nonetheless the case that the radical social-democratic Co-operative Commonwealth Federation (CCF) was regarded as “labour’s party.” Why had this happened? How the CCF and CP related to one another is somewhat obscure, however, in Mickleburgh’s treatments. Nonetheless, it is clear that after World War II, a Cold War unleashed in the unions established anti-communism as the mother’s milk of a consolidating labour bureaucracy. It is perhaps not accidental that the achievement of collective bargaining rights for workers in the immediate aftermath of World War II — a state-supported and monitored system of industrial relations resting on union certifications, contracts that prohibited strikes during the life of negotiated agreements, and a professional corps of trade union leaders expected to police their memberships — occurred at the very same time that the newly-arrived CCF-affiliated labour officialdom launched a struggle to banish Communists from positions of influence in workers’ organizations. Mickleburgh avoids confronting the relationship of these developments.

British Columbia became a centre of this struggle over control of the trade unions. The legendary suspension from the Canadian Congress of Labour (CCL) of an irascible, but effective, Communist B.C. labour organizer, Harvey Murphy, reveals a great deal about just how communists and social democrats clashed, who won, and how, over time, the mores of relating the history of workers have changed.[9]

In Paul Phillips’ 1967 account Murphy, associated with the Communist-led Mine, Mill, and Smelter Workers Union, was said to have attacked CCL national officers at a Victoria banquet held for visiting trade union leaders and government representatives. His language described cryptically as “abusive,” Murphy was tossed out of the CCL for two years, and Mine Mill, not shy of assailing the Congress in the pages of its newspaper, was given the boot from this mainstream House of Labour indefinitely.[10]

Murphy’s drink-driven tirade at the banquet was the stuff of labour lore, referred to more earthily as “the kiss my ass” attack. Mickleburgh, writing with more candour than Phillips could muster, calls it the “Underpants Speech.” Angered by the anti-communism of the CCL leadership, two key figures of which were present on the banquet podium, Murphy lashed out at the support these “Red-baiting floozies” and “phonies” had given to the state’s deportation of Mine Mill’s President, Reid Robinson, targeted for his communism. Gesturing toward the dais, Murphy suggested that there were trade union figureheads in Canada who, when invited to pucker up and plant one on the employer’s ass, would do little more than meekly request that the boss drop his underwear (p. 131).

The axing of Murphy and Mine Mill, however seemingly mundane and coarse, was symbolic of the Cold War victory of trade unionism’s social democratic leadership. As organized workers reaped the benefits of the post-war settlement’s codification of collective bargaining, they did so cleansed of a communist leadership that had once provided a militant spark to class struggle. A layer of trade union leaders schooled in anti-communism ruled the labour movement. To be sure, British Columbia’s working class was more radical and hospitable to dissidents than other provinces; communists continued to play a significant role in unions such as the United Fishermen and Allied Workers, even though such bodies were exiled from the CCL-led House of Labour for years. Yet the Cold War struggle in the unions determined that the politics of organized labour in B.C. would tilt in the direction of social democracy, leaving more radical or revolutionary currents on the margins.

By the 1960s and 1970s the outliers of British Columbia’s organized working class, some still harboring communist sensibilities, would be characterized by their Canadian nationalism, leading breakaways from the Internationals headquartered in the United States. This radical nationalism perhaps first surfaced in the International Pulp, Sulphite, and Paper Mill Workers, where Angus Macphee led a secession movement in the early 1960s that created the Pulp, Paper, and Woodworkers of Canada (PPWC). It soon branched out to establish Canadian locals that aspired to represent disgruntled IWA sawmill workers and employees at Kitimat’s Alcan smelter, unhappy with how they were represented by the United Steel Workers of America. In 1969, with the formation of the Confederation of Canadian Unions, this nationalist mobilization had rallied workers to the Canadian Association of Industrial and Allied Workers (CAIMAW), the Canadian Association of Smelter and Allied Workers (CASAW), and the Independent Canadian Transit Union (ICTU).

A labour leadership that had bare-knuckled it out with the Communists was not about to let these secessionist unionists have a free ride, outside of the B.C. Federation of Labour, dipping their hands into the dues till of the mainstream labour organizations, raiding locals with seeming impunity. A rough-and-tumble Irish immigrant cannery and pulp mill worker, Pat O’Neal, climbed the rungs of the Pulp Sulphite leadership, attaining the union’s presidency in 1952. Soon he moved on to the B.C. Fed’s Executive and, eventually, to its powerful Secretary-Treasurer post. But O’Neal chucked his influential office to return to Pulp Sulphite and dam the drain of members to the nationalist PPWC. He was heartened, if not abetted, by convenient Labour Relations Board decisions that denied the nationalist upstart labour organization status as a bona fide provincial trade union. The Board rejected three certification applications on this spurious ground, even though the PPWC had already secured five previous union confirmations and successfully negotiated a number of collective agreements.

The lengths to which O’Neal was willing to go in order to stifle the nationalist threat to his union were extraordinary: they included hiring a private detective to bug the hotel room of the PPWC’s national president at an annual convention in 1966; and colluding with employers to fire PPWC activists. It was all so unseemly that many in unions like the IWA denounced O’Neal and successfully demanded his removal from the B.C. Fed Executive. Mickleburgh can be glib about the event. In the fallout from the labour movement’s use of surveillance against working-class dissidents, a government inquiry interrogated a PPWC official who refused to answer questions about his political past that suggested possible membership in the Communist Party.

Cited for contempt and facing jail, it seemed that the dissident pulp and paper unionist had been victimized twice, first by the mainstream trade union movement and then by the government and its courts. Mickleburgh’s jocular comment is that the state “exonerated the bugger and punished the bugee” (p. 154). As witty as this rendition may be, it perhaps misses the point: an ensconced labour officialdom was now prepared to go to virtually any and all sordid ends to discipline and defeat radicalism and challenges to its hegemony within working-class circles. This was a troubling trajectory that would not serve trade unionism well.

Breakaway unions were often led by New Left-inflected radicals. They found themselves bolstered by exiles from established craft unions, some of which were rocked by wildcat walkouts in a countrywide wave of illegal strikes in 1964-1966. These raucous job actions were the trade union equivalent of the better-known university campus revolts that traumatized colleges like Simon Fraser and Sir George Williams (now Concordia) a few years later. Spearheaded by young militants, the wildcat wave took aim at employers, to be sure, but it was just as much a revolt against ossified trade union bureaucracies and their counterparts in the state apparatus that struggled to keep the lid from blowing off class relations.

One such angry walkout occurred at the Burnaby plant of Lenkurt Electric in April 1966. As the smoke cleared from the torching of court injunctions, the company refused to hire back 75 of the roughly 260 wildcatters, including all of the members of the shop steward committee. To rub salt in the collective wound, the International Brotherhood of Electrical Workers disciplined the militants. It suspended a business agent who refused to implement a deal brokered to bring the illegal strikers back to work, and kicked rank-and-file wildcatters out of the union. One of these rabble-rousers, Jess Succamore, was suspended from the IBEW for twenty-five years. He took up the cause of breakways, becoming a leader of the Confederation of Canadian Unions and its affiliate, CAIMAW.

Throughout the 1970s, B.C. labour faced a difficult uphill fight against the growing fiscal crisis of the state that would pave the rocky road to austerity. In B.C., a series of tough presidents of the provincial Federation of Labour battled governments, one of which was led by the New Democratic Party’s [NDP] Dave Barrett, whose language of restraint translated into anti-labour policies that soon raised the decibel level of class conflict. Paving the way for the federal wage controls implemented by Pierre Trudeau in 1975, the Barrett government cried that it was facing a “capital strike” and looked to its friends in the unions to bail it out by voluntarily curbing wage demands. In the runaway inflation of the era, these routinely topped twenty percent yearly and occasionally soared to annual extremes of fifty percent. Not giving ground, the unions turned en masse to strikes in the hot summer of 1975. Bakers, meat cutters, railway workers, truck drivers, and others walked out.

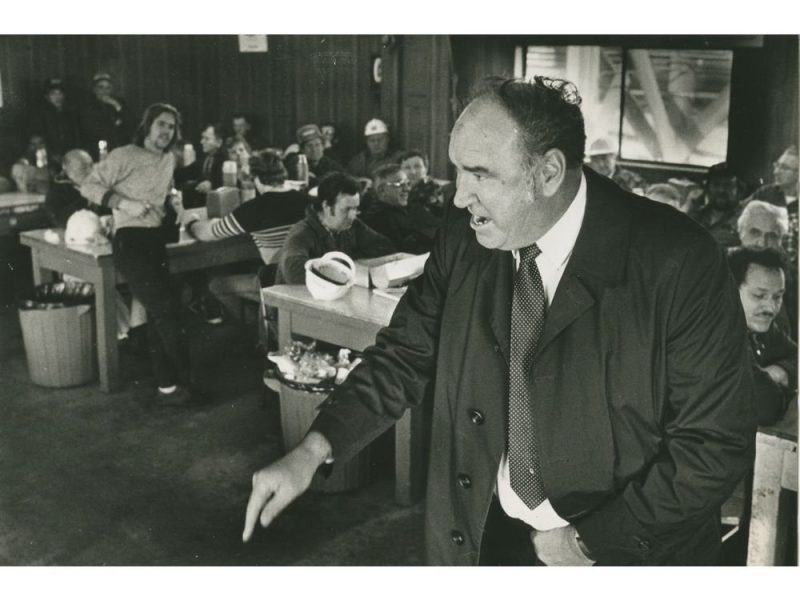

In the province’s dominant forest industry the threat of class struggle chaos was most inflamed. The Employer’s Council, emboldened by a softening lumber market and a worldwide glut in pulp stocks, decided to draw a line in the sand. It offered the three unions in this jurisdiction (the PPWC and Pulp and Sulphite’s successor, the Canadian Paperworkers Union, as well as the International Woodworkers of America) a one-year contract with no wage increase save for a cost of living adjustment. The insult united the two warring unions in the pulp and paper sector, whose leaderships quickly orchestrated job action. A deeply divided IWA was kept at the bargaining table by Jack Munro, who urged acceptance of the companies’ terms rather than join a strike he saw as doomed to defeat.

Things only worsened when the striking pulp workers took their pickets to IWA mills. As Munro blasted the “super militants” for “spreading their mess around,” his counterparts in the two other forestry sector unions denounced the IWA’s go-it-alone breach of solidarity and defiant quietude in the face of class conflict fomented by the bosses. With strikes ricocheting off one another, Barrett chimed in with back-to-work legislation that gave 50,000 workers, including the negotiating IWA, 48 hours to settle up and return to work. The obnoxious legislation, Bill 146, outraged B.C. Fed President Len Guy, who called it outright strikebreaking and a betrayal of the supposedly historic NDP-labour relationship. Guy offered support to any union that would disobey the order to cease striking. In spite of pulp and paper workers’ leaders predicting “total warfare,” he found no takers (pp. 186-187). Munro was not amused, lashing out at those critical of Barrett and the NDP.

The stage was thus set for the Solidarity showdown, a rumble in the jungle of B.C.’s class warfare. If the mid-1970s battle with Barrett was one thing, a titanic clash was in the 1980s offing. With the material circumstances of British Columbia continuing their downward slide and the levers of government in the hands of New Right advocates of Restraint Economics such as the Social Credit Premier, Bill Bennett, the province was subjected to a hard-nosed dose of shock therapy. The ills of an overregulated and atrophying political economy were to be cured by an all-out assault on the poorest and weakest segments of the population, and the one group of strength that purported to act on behalf of this contingent of the downtrodden, the trade unions. The terms of class war were being reversed, waged from above as opposed to from below.

Returned to office in 1983, the Social Credit Party led by Bennett unleashed a budget that slashed and burned pivotal planks in the welfare state and targeted public sector labour organizations, whose collective agreement rights were virtually obliterated. The resulting mobilization, which grew originally out of a spontaneous resistance led by left caucuses in the unions, community activists, and, especially, disgruntled feminists, was rather quickly placed under the leadership of the British Columbia Federation of Labour and its head, a liberal Cold War warrior, Art Kube. As many writings have suggested, and as Mickleburgh’s account reveals, the Solidarity uprising was arguably British Columbia labour’s most significant mobilization, “a people’s movement that has come around only once in the province’s history” (p. 229).

Between 7 July 1983, when the Socreds introduced their budget bills and 13 November 1983, the Solidarity mobilization united trade unionists and social activists in legally-sanctioned strikes; illegal job actions and walkouts; massive public protests in metropolitan centres like Vancouver and Victoria; workplace occupations in smaller interior communities; the creation of an alternative newspaper, Solidarity Times; and the timetabling of strike actions by crucial work sectors such as the ferry workers. The aim was proclaimed to be the repeal of the entire repressive legislative package, the commitment made to launch a General Strike (at least vaguely and grudgingly) if the state moved to implement back-to-work legislation or take other repressive action.

Hundreds of thousands of B.C.ers had marched, rallied, and met in nightly meetings across the province; 200,000 workers were poised to make unprecedented use of political strikes against the government. And then, abruptly and arbitrarily, it was over.[11]

The details of Mickleburgh’s recounting of Solidarity’s rise and fall are not so much wrong as partial and incomplete, irretrievably tone deaf. And here it is difficult not to suggest that the ringing importance of the Solidarity fightback has not been drowned out in the bureaucratic tune of bluster and bravado characteristic of the trade union leader who has clearly paid the piper for this history of British Columbia workers, Jack Munro.

For Munro, at least symbolically, ended the Solidarity struggle, flying to Kelowna to appear with Bennett and turn off the taps of an intense, five-month class struggle as all-encompassing as anything ever seen in Canada. In Bill Bennett’s house, “Jack Munro/took out his wallet/and placed it on a table. Jack Munro sold out this province/ house by house,/ district by district,/ kilometer by kilometer. How could it occur/that direction of our struggle/ fell to one man?” The words are those of Tom Wayman, poet laureate of the B.C. left in the 1980s. Wayman’s “The Face of Jack Munro” presents a picture of the labour porkchopper, his ruddy countenance “puffy with greed and fright and satisfaction.” Munro’s words and actions voiced no commitment to the workers movement’s original slogan, “An Injury to One Is An Injury to All.” Rather, they echoed Sam Gompers’ business unionist craft sectionalism, worshipping at the shrine of self-interest. For many, it all confirmed “Solidarity Forever’s” reminder that, “Yet what force on earth is weaker than the feeble strength of one.”[12]

On one level this kind of seemingly personalized condemnation is harsh, and in its apparently literalist assigning of responsibility to one man, untrue. For Munro did not act alone. But as a metaphorical representation of a layer of conservative trade union officialdom, which was Wayman’s intent, it is apt enough. And if Munro’s rather large shoes fit, then he must wear them and the consequences they walked us all toward. Munro did everything to keep the IWA members he led out of a strike during the Solidarity struggle, at a time when they were in a legal position to refuse work. Had the woods workers joined the protest through industrial action this would have been regarded by tens if not hundreds of thousands of British Columbians as an unambiguous act confirming the collective strength of the working class, a demonstration repudiating the government’s politics of coercive restraint.

Munro did all of this and more to scuttle Solidarity and solidarity, and he did it boastfully and defiantly, titling the first chapter in his autobiography, Union Jack (1988), “Derailing the Solidarity Express.”[13] Munro thus had very little to do with Solidarity’s making, although he was undoubtedly a voice within the B.C. Federation of Labour castigating the militants and decrying the demand that the entire repressive legislative package of the Socred’s 26 Budget Bills be withdrawn or the consequence would be a General Strike. But he was there, in the end, to preside over its corpse, which he had helped to lay out on the funeral pyre. In this refusal to break from a fundamental tenet of the post-war settlement, the limits that a state-codified system of industrial relations placed on what could and what could not be bargained, Munro spoke for a layer of trade union officialdom whose authority rested on an axiom that “social issues could not be won on a picket line.”[14]

Munro did all of this and more to scuttle Solidarity and solidarity, and he did it boastfully and defiantly, titling the first chapter in his autobiography, Union Jack (1988), “Derailing the Solidarity Express.”[13] Munro thus had very little to do with Solidarity’s making, although he was undoubtedly a voice within the B.C. Federation of Labour castigating the militants and decrying the demand that the entire repressive legislative package of the Socred’s 26 Budget Bills be withdrawn or the consequence would be a General Strike. But he was there, in the end, to preside over its corpse, which he had helped to lay out on the funeral pyre. In this refusal to break from a fundamental tenet of the post-war settlement, the limits that a state-codified system of industrial relations placed on what could and what could not be bargained, Munro spoke for a layer of trade union officialdom whose authority rested on an axiom that “social issues could not be won on a picket line.”[14]

This ideology of industrial pluralism, which confines class struggle to what can legally and legitimately be addressed in collective agreements, is of course simply not true historically. It is evident — the narrative of workers’ actions in On the Line demonstration enough — that working-class militancy and class struggle have indeed won breakthroughs on social issues. After all, the right to organize, form unions, and establish collective bargaining, were once considered just such an impossible political aspiration. Indeed, the labour movement as it came to exist in the post-World War II years of recognition and growth, benefitted from countless struggles that pushed the envelopes of legality and respectable behavior to aggressively demand new understandings of what was possible.[15] Restricting the power of trade unions to up the ante and fight for issues that Munro and others in the cautious labour leadership considered the proper socio-political terrain of their parliamentary arm, the New Democratic Party, failed to appreciate how much the Socreds and what would come to be known as neoliberalism, were changing the rules of the industrial pluralist game.

The intention of those forces committed to restraint and austerity was to defeat the powerful unions as part of a broader program of widening the net of dispossession by deregulating the social order and dismantling the welfare state, another institution created in the post-war period that owed much to workers’ struggles and unprecedented stands of audacious demand. When Munro and others stood against the Solidarity struggle to turn this tide back in order, in their view, to preserve the narrowed right of collective bargaining, they smugly tied their hands of combat behind their backs. This would weaken trade unionism and squash its historic responsibility to speak, not only for a narrow dues base, but for a wider constituency of the dispossessed, of which the organized working class has been but one of a number of components, albeit a decisively powerful one.

Against the “Not in My Backyard” parochialism of Munro and an ossified officialdom, Solidarity as a movement threatened to reinscribe on the banner of modern-day trade unionism labour’s original, animating slogan, “An Injury to One is an Injury to All.” But Munro, the personification of a trade union bureaucracy forged on the anvil of class struggle cooled down by state accommodation, was having none of this return to first principles.

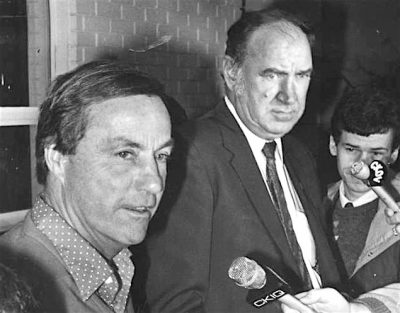

Mark Zuelke’s photo of Bill Bennett and Jack Munro as they announce a deal to end Operation Solidarity, November 14,1983.

What Munro “negotiated” with Bennett in Kelowna was thus nothing less than a critical truncation of an attempt to fight to win against a foe that, admittedly, held a very strong hand. Less an act of saving grace, as it has been presented by Munro and Mickleburgh, Solidarity was a defeat. It reveals, in its representative clarity, the problem at the core of On the Line: a failure to explain the changing contours of working class life and the struggles that grow out of this constant recomposition; a twisting of that history to the instrumental purposes of the present, which inevitably suppresses the initiatives and complexities of mass struggles and adapts them to compromises and conciliations that, in their internal logic, continue the process of working-class subordination.

Moreover, as many in British Columbia’s trade union movement and social activist circles will tell anyone willing to listen, what was lost in 1983 lingered for years, perhaps decades, hanging over the working class and its advocates for a long time. The politics of progressive resistance to the New Right and militant opposition to the evolving ideology of neoliberalism was set back in British Columbia by what happened in the Solidarity debacle. It took a long time to recover, and reignite the spark of resistance.

As Mickleburgh acknowledges, most of what was seemingly agreed to at Labour Relations Board meetings involving the B.C. Fed hierarchy and government representatives before the infamous tête-a-tête between Bennett and Munro in the premier’s private, Kelowna residence, went by the class collaborationist wayside. Bennett got Munro where he wanted him, played hardball, and refused to commit any of the agreement that would end the escalating Solidarity actions to paper. Indeed, there are sources who claim that as Munro boarded the government plane to fly to Kelowna, Bennett’s advisor, Norman Spector, looked at him and sneered, “We’ve got you now. We are going to renege.” It the end, little was delivered, except the already negotiated settlement with the striking British Columbia government employees, and while something was gained in that contract it was by no means a resounding win for the workers.[16]

Mickleburgh presents the BCGEU settlement as central to the “trade union victories” of Solidarity, but you could not have fooled the 1600 government employees pink-slipped at the time with that claim. To be sure, two of the Budget’s most offensive clauses, Bills 2 and 3, aimed at gutting public sector unionism, were tabled in the BCGEU settlement, the worst of their draconian substance drained away from having a disastrous impact on the union. But the offensive Bills themselves remained in force. Other public sector workers were left to negotiate their way out from under the Damocles Sword that remained poised over their exposed necks.

The B.C. Teachers Federation, led by Larry Kuehn (who is never mentioned in the account of Solidarity in On the Line), paid the largest price. This is not surprising since it was the BCTF that had given Solidarity a huge boost with its dramatic socially-animated strike action in November, a militant walk-out that snubbed its nose at a raft of state-issued injunctions, and that defied Munro’s claim that strike action and social issues were irrevocably separate. Many of the old guard at the pinnacle of the B.C. Fed were shocked by the teachers’ capacity to pull off an effective strike against the odds and in defiance of all of those who claimed their Solidarity-inspired job action was illegal and would wither in the face of public animosity and the threat of state reprisal.

It is difficult to discern who loathed Larry Kuehn more, Jack Munro or Bill Bennett. And so it is not all that surprising that the education sector, which was supposed to benefit from the money saved by the government during the BCTF strike, would be stiffed, and Kuehn assailed by the state, the trade union tops, and the “party of labour,” the NDP. Mickleburgh presents the teachers emerging from Solidarity as “victors” (p. 229) Heroes they were; victors they most emphatically were not. As an act of solidarity, the so-called Kelowna Accord was a bitter pill of repudiation.

Mickleburgh acknowledges that Solidarity’s anticlimactic end left a bad taste in many activists’ mouths. He does not, however, come close to explaining how sorry the denouement of November 1983’s debacle actually was.

The dressing up of Jack Munro into the “imposing leader” whose realism terminated the activist adventure is actually quite unseemly, given that it fails to address the ugliness of what went into the IWA leader’s stance. Mickleburgh, for instance, refers to the “intemperate remarks” of Munro about the Solidarity activists, who included tens of thousands of rank-and-file union members as well as community organizers and dedicated militants in various social justice constituencies, not to mention BCGEU-and-BCTF-affiliated workers, who sustained the strike actions that actually extracted concessions from the state.

Since Munro was not shy about putting his worst foot forward, sticking it in his mouth, it is appropriate to quote just one such statement, leaving it to the reader to assess whether a word such as “intemperate” actually captures what was being said:

The Bennett government created the climate to put together a whole raft of groups of people who never, ever really had the ability to get together before. These groups of people all of a sudden find this fantastic power where people are talking about strikes in the public sector and general strikes in the private sector and all this. Shit, they thought, this is fuckin’ great. The same people who had never ever in their goddamned life … ever thought that they would sit down at an executive board and make these kinds of decisions. Like, where the hell would you ever get enough people to attend the Rural Lesbians’ Association fuckin’ meeting … sitting next to the Gay Alliance, sitting next to the Urban fuckin’ Lesbians, and all this horseshit that goes on in this fuckin’ world these days, making a decision to shut the province down. It was great. Trade unionists … we were the turkeys in the goddamned thing. Chicken-shit trade unionists. You could feel that we were the goddamned moderates, for Christ’s sake. I should have been for all these causes, a lot of causes that I don’t goddamned agree with. I should have been asking our people, who maybe were going into a strike situation of our own, to come off the job. Well that isn’t the way the real world works.[17]

Intemperate, yes. But more to the point, these words were an articulation of bravado and bureaucratic power enamoured of its own entitlements. They speak, not so much of facts and realities, as they display an officialdom’s self-serving and complacent assessment of its reality, one in which both Solidarity and solidarity meant little and the labour movement’s capacity to use its power to defend principles and people subject to abuse by powerful interests was sacrificed in the narrowest of considerations. This tirade, interestingly, used homophobic caricature as a surrogate for an assault on all of those social elements who committed themselves to an extra-parliamentary struggle against a regressive Social Credit budget. It relied on such offensive typecasting to place an expansive class struggle beyond the pale.

Solidarity, then, was indeed “one of the noblest chapters in the history of the B.C. labour movement,” as Mickleburgh writes (p. 229). This had nothing to do with Jack Munro, however, as imposing as he may have been and as respectfully as this book is dedicated to his memory. Instead, Solidarity’s accomplishments and example had everything to do with the hundreds of thousands of rank-and-file workers and social activists who stood for the kind of nobility that Munro dismissed and disrespected. In the end, one does not have to argue that Jack Munro stood with Bill Bennett, but in any discussion of Solidarity that image, lingering still in the minds of so many, must at least be confronted.

Solidarity, then, was indeed “one of the noblest chapters in the history of the B.C. labour movement,” as Mickleburgh writes (p. 229). This had nothing to do with Jack Munro, however, as imposing as he may have been and as respectfully as this book is dedicated to his memory. Instead, Solidarity’s accomplishments and example had everything to do with the hundreds of thousands of rank-and-file workers and social activists who stood for the kind of nobility that Munro dismissed and disrespected. In the end, one does not have to argue that Jack Munro stood with Bill Bennett, but in any discussion of Solidarity that image, lingering still in the minds of so many, must at least be confronted.

It was also estimated that 25,000 Solidarity protesters appeared at the Legislature in July of 1983.

It was indeed very much in the collective consciousness of the working class, which, at the November 1983 B.C. Fed convention rejected the trade union officialdom’s report on Operation Solidarity, insisting that it lacked militancy and direction.[18] In addition, delegates to that convention voted Jack Munro out of his B.C. Federation of Labour Vice-Presidency, electing in his stead a long-standing rival, Art Gruntman of the Canadian Paperworkers Union.[19]

But the working class is generous, and its memory sometimes sadly short. Munro was soon back in the good graces of the B.C. Fed and when he led the IWA on a bitter, seventeen-week strike in 1986, a prescient battle over pensions and contracting out that whittled the union’s strike fund down to a measly $20 bill, unions across B.C. and throughout the country came to the defence of the beleaguered woods workers. The Canadian Labour Congress and the British Columbia Government Employees Union each loaned the IWA $1 million and, in total, $8 million was raised to support the strike. But the days of the burly logger as the poster-boy of B.C. labour were over. The industry was in decline, and the IWA’s membership shrinking. Breaking from the International to form a Canadian union in 1986, the IWA was no longer the centrepiece on the provincial trade union table, and in 2004 it merged into the United Steel Workers of America.

As Mickleburgh’s final chapters show, the torch of working-class militancy in the last decade of the twentieth century and into the opening decades of the twenty-first, has passed from old-style industrial unions like the IWA to the public sector. Militant strike action is now less likely to take place in the mills, on the docks, or throughout the workforces associated with resource extraction. Rather, job actions and class struggles are dominated by teachers, hospital workers, and government employees, who are providing the most dramatic recent examples of labour confronting a recalcitrant employer.

As often as not this “boss” is the all-powerful state with billions of bucks in its budget, and the police and the courts at its disposal. Women are now likely to be “manning” picket lines, and the working class warriors of modern-day class struggle are increasingly drawn from racialized groups. Mickleburgh’s contemporary story line of class struggle includes accounts of advances for agricultural workers, many of whom are East Indian, and illuminating discussions of the largely immigrant labour force that currently sustains various kinds of public sector work, toiling as cleaners, laundry workers, and food dispensers. Sadly, however, the last chapters of this book alternate between the details of strikes, so often waged against government cutbacks and coercions, and the carnage of industrial accidents and work-related injury and disease. The fights now waged by the working class are increasingly defensive, aimed at curbing cutbacks and securing entitlements under threat; jobs, meanwhile, continue to be deadly and dangerous.

When the 57th Convention of the B.C. Federation of Labour met in 2016, 950 delegates represented 500,000 workers. As always, they came from distinct walks of life, but for the first time the provincial Federation was headed by a woman and a public sector unionist, Irene Lanzinger, a veteran of the British Columbia Teachers Federation. Mickleburgh applauds Lanzinger’s public proclamation that the labour movement embraces workers’ economic struggles as well as mobilizations for social justice, battling “racism, sexism, ableism, homophobia, transphobia, and xenophobia.” Yet he offers no reflections on how this squares with this book’s relationship with the ghost of Jack Munro and the legacy of Solidarity. Does Lanzinger’s rhetorical stand mean very much when the same B.C. Fed that she speaks for has worked so hard to produce a book that licenses so much that actually repudiates this commitment to social causes reaching beyond wages and conditions?

The last chapter of On the Line proclaims, “The Struggle Continues.” This was the refrain that I heard all too often in the aftermath of Solidarity’s kneecapping by the trade union officialdom in November 1983. Is this mantra, routinized amidst an intensifying crisis of the labour movement, a call to action or a retreat into nostalgia, a convenient cover for a multitude of sins that can now be clearly identified but that remain as corrosive as ever?

As Marx once said, “The tradition of all the dead generations weights like a nightmare on the brain of the living.”[20] Labour’s traditions are rich indeed, and British Columbia’s working-class heritage is arguably one of the richest of all. But if the meaning of this heroic past is to be translated into our present, its nightmares have to be confronted and excoriated, as well as its dreams extolled. On the Line takes us to many places that we need to go if we are to turn the oppressive weight of so many nightmares into the liberating lightness of our dreams realized. But it leaves some obvious, at times frightful, happenings unexamined, and too much unexplained.

*

Bryan D. Palmer, a Fellow of the Royal Society of Canada, former editor of Labour/ Le Travail (1997-2018), and a past Canada Research Chair in the Canadian Studies Department at Trent University (2001-2015), lives in Peterborough, Ontario. He is the author/editor of more than 20 books, the most recent of which, co-authored with Gaetan Heroux, is Toronto’s Poor: A Rebellious History (Between the Lines: 2016). In 1983, like hundreds of thousands of British Columbians, he was a part of the Solidarity uprising. He attended meetings, marched in protest, walked picket lines while being on strike at Simon Fraser University, wrote for the Solidarity Times, and served as an alternative delegate for the New Westminster Solidarity Coalition. His account of these tumultuous times is Solidarity: The Rise and Fall of an Opposition in British Columbia (New Star: 1987).

*

The Ormsby Review. More Books. More Reviews. More Often.

Reviews Editor: Richard Mackie

Reviews Publisher/Designer: Alan Twigg

The Ormsby Review is a journal service for serious coverage of B.C. books and authors, hosted by Simon Fraser University. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Robin Fisher, Cole Harris, Wade Davis, Hugh Johnston, Patricia Roy, David Stouck, and Graeme Wynn. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. As of September, 2018, Provincial Government Patron: CreativeBC

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

[1] Paul Phillips, No Power Greater: A Century of Labour in British Columbia (Vancouver: BC Federation of Labour/Boag Foundation, 1967), p. 159.

[2] Gustavus Myers, History of Canadian Wealth (Chciago: Charles H. Kerr, 1914).

[3] Phillips, No Power Greater, p. 165.

[4] Quoted in Ian McKay, Reasoning Otherwise: Leftists and the People’s Enlightenment in Canada, 1890-1920 (Toronto: Between the Lines, 2008), p. 365.

[5] Justine Hunter, “Unearthing long-forgotten BC History. First Nations People and Chinese immigrants forged a bond centuries ago. Now archaeologist are documenting their common ground,” Globe and Mail, 9 May 2015.

[6] A. Ross McCormack, Reformers, Rebels, and Revolutionaries: The Western Canadian Radical Movement, 1899-1919 (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1977), p. 63.

[7] Still useful on Kingsley is the somewhat dated discussion in McCormack, Reformers, Rebels, and Revolutionaries, pp. 15, 60-61. Note a source that Mickleburgh could not have consulted, published too late for his consideration: Mark Leier, “Bearing the Marks of Capital: Solidarities and Fractures in E.T. Kingsley’s British Columbia,” in Ravi Malhotra and Benjamin Isitt, eds., Disabling Barriers: Social Movements, Disability History, and the Law Vancouver and Toronto: UBC Press, 2017), pp. 13-26. Arguably the most well-known historian of labour in British Columbia, it is surprising that Leier is largely absent from On the Line. The only Leier title that appears in the bibliography is Where the Fraser River Flows: The Industrial Workers of the World in British Columbia (Vancouver: New Star Books, 1990).

[8] Peter Campbell, “East Meets Left: South Asian Militants and the Socialist Party of Canada in British Columbia, 1904-194,” International Journal of Canadian Studies, 20 (Fall 1999), pp. 35-65.

[9] Murphy has been the subject of recent discussion in two articles by Ron Verzuh: “#19 Trade Unionist Harvey Murphy,” BC Booklook, 22 September 2016; “Proletarian Cromwell: Two Found Poems Offer Insights into One of Canada’s Long-Forgotten Communist Labour Leaders,” Labour/Le Travail, 79 (Spring 2017), pp. 185-227. See, as well, Stephen L. Endicott, Raising the Workers’ Flag: The Workers’ Unity League of Canada, 1930-1936 (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2012).

[10] Phillips, No Power Greater, pp. 143-144.

[11] I have offered my own discussion of Solidarity, which includes a full narrative account of the development of the movement, its purpose, and an interpretation of why it failed. See Bryan D. Palmer, Solidarity: The Rise and Fall of an Opposition in British Columbia (Vancouver: New Star, 1987). Somewhat congruent with my analysis, and quite different than the presentation in On the Line, is the recent short presentation in David Spaner, “The Unknown Revolution: BC’s Solidarity Uprising of 1983,” subTerrain, 79 (Spring 2018), pp. 54-61.

[12] For the full range of Wayman’s poetic recounting of the end of Solidarity see Tom Wayman, “The Face of Jack Munro,” Canadian Dimension, 20 (March 1986), pp. 16-17, reprinted in Wayman, The Face of Jack Munro (Madeira Park: Harbour Publishing, 1986).

[13] Jack Munro and Jane O’Hara, Union Jack: Labour Leader Jack Munro (Vancouver/Toronto: Douglas & McIntyre, 1988), pp. 1-17.

[14] Munro and O’Hara, Union Jack, p. 3.

[15] See, for instance, Bryan D. Palmer, “What’s Law Got to Do With It? Historical Considerations on Class Struggle, Boundaries of Constraint, and Capitalist Authority,” Osgoode Hall Law Journal, 41 (2003), pp. 466-490.

[16] For a fuller discussion see Palmer, Solidarity, pp. 72-81.

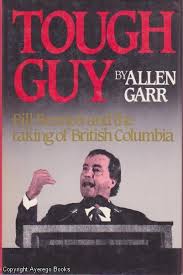

[17] Munro quoted in Allen Garr, Tough Guy: Bill Bennett and the Taking of British Columbia (Toronto: Key Porter Books, 1985), pp. 141-142.

[18] This seemingly inconsequential post-mortem does not, of course, find its way into Mickleburgh’s 2018 account of Solidarity in On the Line, but he was certainly aware of it, having written about it as a journalist in Rod Mickleburgh, “Weak Solidarity war plan rejected by delegates,” Province, 30 November 1983.

[19] Munro and O’Hara, Union Jack, pp. 17.

[20] Karl Marx, “The Eighteenth Brumaire of Louis Bonaparte,” in Karl Marx and Frederick Engels, Selected Works Moscow: Progress, 1968), 97.

Peace made with B.C.’s labour unions in 1983 enabled Premier Bill Bennett to welcome Prince Charles and Princess Diana for Expo 86.

Thank you for sharing your expertise on labour history in BC. It’s important for people to understand their rights and know they have options. I appreciate the valuable information you provided.