#349 A carpenter poet adept at forms

August 23rd, 2018

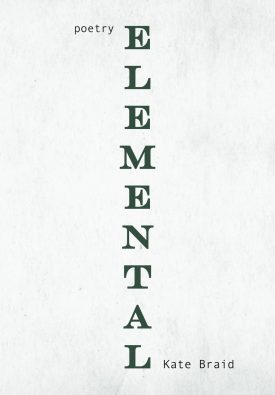

Elemental

by Kate Braid

Halfmoon Bay: Caitlin Press, 2018.

$18.00 / 9781987915631

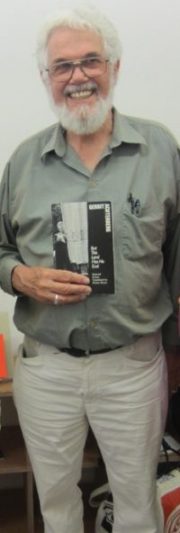

Reviewed by Christopher Levenson

*

Christopher Levenson admires the “archetypal west coast experiences” explored by Kate Braid in Elemental, a series of poems grouped by the five elements: water, fire, wood, sky, and earth. Braid “deftly covers a whole range of tones and of experiences, both personal and communal, to create her own world of curiosity and reverence.” — Ed.

*

Despite the book’s title and its division into five elements — water, fire, wood, sky, and earth — the dominant feature of Elemental, Kate Braid’s seventh book of poetry, is less unity of theme or focus than her unobtrusive craft and her concern with texture, both physical and psychological.

Despite the book’s title and its division into five elements — water, fire, wood, sky, and earth — the dominant feature of Elemental, Kate Braid’s seventh book of poetry, is less unity of theme or focus than her unobtrusive craft and her concern with texture, both physical and psychological.

Braid knows exactly what she is doing as a poet. As someone who has literally (co-)written the book on poetic form — In Fine Form: The Canadian Book of Form Poetry (Caitlin Press, 2014) — she is, not surprisingly, adept at forms such as palindromes and, especially, glosas.

Important indicators occur, for instance at the beginning of “Opening the cabin:”

We have come to the cabin after weeks

in the smoke of city living, climb out of the car

crisp with caution

The language of good poetry works cumulatively with so much depending on a single word — here it is “crisp” — that jolts us to attention by its unexpected rightness and accuracy. Noting this prepares the reader to accept Braid’s claim later in the same poem that “it is in moving that our bodies come to know/ where we are,” or her conclusion elsewhere that, “How needy we are and don’t know it.”

Geographically where we are in her book is B.C., and many of these poems, such as “Small boat” or “Tattoo” evoke archetypal west coast experiences, but clearly for Braid the most essential of these five elements is wood. Having worked for fifteen years as a carpenter, her natural feel for that element, already central in such poems as “Younger Sister” and “The Wood Hanging,” develops naturally into a symbiotic relationship with trees that extends far beyond standard New Age mysticism. Thus, in “For Jude, the Cabinet Maker in his Shop,” we find:

the forester says.

if disease strikes a tree at one side of the forest, the rest

simultaneously make antibodies. Like a cathedral,

one pillar relying on every other to create a sacred space

each element in touch, alive — moulds to roots to leaves to creatures

visible and invisible, trees and mosses, insects and birds.

Is this what we call holy, this connection of the whole,

each to every other?

Thanks to Peter Wohlleben’s The Hidden Life of Trees (Greystone: 2016), such concepts, along with the effect that walking through forests may have on our brains, have now gained wider acceptance — but they still need the concise articulation of poetry to fully engage the imagination.

While some of Braid’s frequent incursions in dream and fantasy strike me as less convincing, the comments that arise when speculation starts from a very specific incident are far more suggestive, as here in “Monolith,” where “five feet of polished grey stone” has been disinterred:

She might have been the perfect monolith

for water to run over or flowers to cascade down.

Instead she lies dug up, just another inconvenience

to those who live on the surface

Clearly Braid is not one of those who live “on the surface.” And sometimes, as in “Lava,” and later in “Autobiography of stone,” she imaginatively becomes her subject:

Think of me as your heart’s blood

One day slow, unheeded inevitable

as an underground river

next day bursting margins, veins

boundaries

Indeed, throughout the book Braid is very good at asking searching questions of the world around her. Yet for me she is at her strongest when conveying the textures of things, places, events, and their accompanying emotions, as in “The Day of the Carr Family Auction:”

…. Remember the plain scaredness Doug admitted later,

that today twenty years of their work would be judged. Today

they might lose everything

as Betty stops to welcome the man who

for all those years sold them fertilizer and chemicals.

Now come all the way from Edmonton to say thank you,

Goodbye.

Remember the Hutterite, dark raven with his black cap

pulled low against the cold, clear spotlight of space around him

as he hovered over the freshly painted augur.

Remember him hitching it to his truck to take home,

the shadow of a smile as he drove past.

For more than two pages the details of individual lives are casually interwoven to create a complex amalgam of feelings all anchored to things. Nor is this the only instance. “How to Homestead,” dedicated to the memory of her grandmother, reminds one of Margaret Atwood’s “Progressive Insanities of a Pioneer” in its directness, sparseness, and ironic realism in its advice:

Practise a local vernacular

Listen for your own tongue.

Pretend you don’t see the Cree,

the ones who came first.

Pretend you’re alone.

Most of the time you are….

… After a while you can’t hide

from the neighbours

(if you have any).

If you’re a woman,

practise going crazy….

Here, as elsewhere, while often drawing for inspiration upon the work of other, especially female, writers and visual artists, Braid deftly covers a whole range of tones and of experiences, both personal and communal, to create her own world of curiosity and reverence.

*

Born in London, England 1934, Christopher Levenson came to Canada 1968 and taught English, Creative Writing, and Comparative Literature at Carleton University from 1968 to 1999. He has also lived and worked in the Netherlands, Germany, Russia, and India. He has written twelve books of poetry, the most recent of which is A tattered coat upon a stick (Quattro Books, 2017). He co-founded Arc magazine in 1978, was its editor for the first ten years, and was for five years Series Editor of the Harbinger Press imprint of Carleton University Press, which published exclusively first books of poetry. He has reviewed widely, mostly poetry and South Asian literature in English, in the UK and Canada. With his third wife, Oonagh Berry, Christopher moved to Vancouver in 2007 where he helped re-start and run the Dead Poets Reading Series.

*

The Ormsby Review. More Books. More Reviews. More Often.

Editor/Designer/Writer: Richard Mackie

Publisher/Writer: Alan Twigg

The Ormsby Review is a journal service for serious coverage of B.C. books and authors, hosted by Simon Fraser University. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Robin Fisher, Cole Harris, Wade Davis, Hugh Johnston, Patricia Roy, David Stouck, and Graeme Wynn. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. As of September, 2018, Provincial Government Patron: Creative BC

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

Leave a Reply