#347 Kinsella – a life like no other

August 22nd, 2018

Going the Distance: The Life and Works of W.P. Kinsella

by William Steele

Douglas & McIntyre

September 1, 2018.

$34.95 / 9781771621946

Reviewed by Sheldon Goldfarb

W.P. Kinsella was loved by readers, disdained by the establishment. William Steele’s bio reveals the fascinating and perplexing private life of Canlit’s most cantankerous genius.

*

Editor’s Note: It’s possible, even likely, that the stories of the late W.P. Kinsella will still be widely read fifty years from now; more so than any other B.C. fiction writer with the exception of Douglas Coupland and Alice Munro (whose work Kinsella greatly admired).

Editor’s Note: It’s possible, even likely, that the stories of the late W.P. Kinsella will still be widely read fifty years from now; more so than any other B.C. fiction writer with the exception of Douglas Coupland and Alice Munro (whose work Kinsella greatly admired).

Meanwhile, reviewers like to carp on his personality and the contemporary issues of cultural appropriation. Kinsella is viewed as childish, awkward, cranky, “American,” commercial and decidedly unsexy. His work is largely disregarded–and therefore disrespected–largely because he himself was not congenial, polite, collegial or “politically correct.”

*

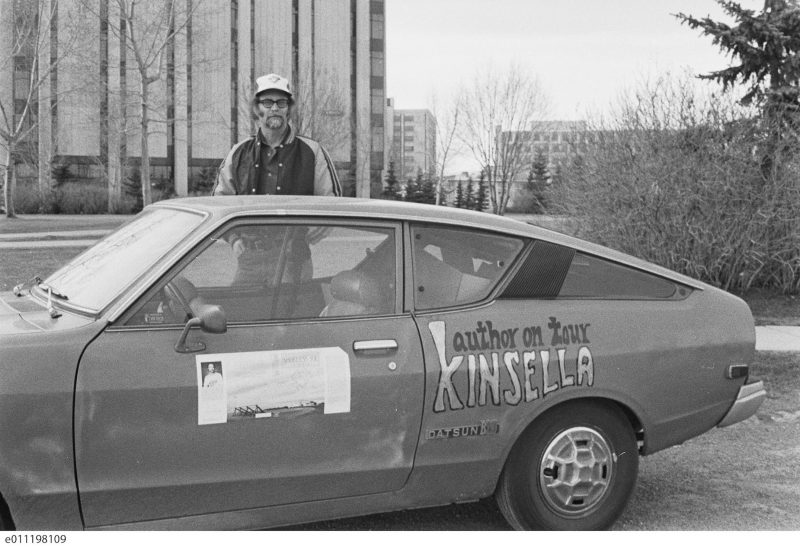

W.P. “Bill” Kinsella launches his book tour for Shoeless Joe in 1982 with his partner Ann Knight’s Datsun.

Sheldon Goldfarb’s review: There’s something puzzling early on in this biography of W.P. Kinsella. Kinsella, famous for the iconic “If you build it, he will come” line in his baseball novel, Shoeless Joe, was the son of an American father who, William Steele tells us, went back to the United States in 1914 to join the army and fight in the First World War.

Wait a minute, you think. The Americans didn’t enter the war till 1917. There must be something wrong here. You check the footnotes. There is indeed a reference for this statement: it’s to unpublished notes by W.P. Kinsella. Hmm. So the source is a recollection by the younger Kinsella, perhaps repeating a story his father told him. Are there no army records to check to clear this up?

Apparently not, or at least the biographer didn’t look for them.

Kinsella’s father John with his wife Mary Olive and their only child Billy outside their isolated home near Darwell, Alberta, circa 1939.

Then you notice that the vast majority of notes in this book are to unpublished notes or diaries of W.P. Kinsella, sometimes to personal interviews with W.P. Kinsella. William Steele has certainly done part of his homework: checking with his subject, learning all that he had to say about his own life. But there’s more to a biography than that.

When describing the end of Kinsella’s first marriage, Steele reports that Kinsella didn’t really understand what happened: “only Myrna knew for sure.” Okay, so what does Myrna say? We aren’t told. The biographer didn’t speak to Myrna – or anyone else about the marriage or most of the other events in Kinsella’s life.

After a while you begin to wonder if this biography is actually a funny trick being played on us from beyond the grave by the creator of that Indigenous conman, Frank Fencepost. Maybe this is really Kinsella’s autobiography rewritten in the third person. Maybe there really is no William Steele. There were people who thought Shoeless Joe was written by J.D. Salinger (because Salinger appears in the book); Kinsella appears in this book …

But no, I am assured that there really is a William Steele, a professor of English in Tennessee. It’s interesting that the first biography of Kinsella should be written by an American. There is something very American about Kinsella, even though he was born in Alberta and lived about half of his life in British Columbia. He is known after all for a baseball novel set in Iowa, and what we learn in this biography is that despite being awarded the Order of Canada and the Order of British Columbia, Kinsella always felt rejuvenated when he could escape to California or Hawaii or his beloved Iowa. He would say how he wouldn’t stay in Canada if not for the free medical care. When he taught at the University of Calgary, which he nicknamed Desolate U., he confided in some private notes: “I HATE CALGARY” and “I HATE THIS COUNTRY.” Admittedly, this was after getting his heating bill during a cold snap. Still …

Kinsella once gave an interview in which he was at pains to call himself a North American rather than a Canadian writer, and then was upset when this turned into a statement that he was an American writer. At least, our biographer says Kinsella was upset. Was he really? Perhaps upset about a potential loss of sales in Canada, because another thing that emerges from this biography is how obsessed Kinsella was with money. He decided not to write poetry because there was no money in it. He almost didn’t turn the original short story about Shoeless Joe into a novel because he knew he was making steady money producing short stories and taking time out from that to try his hand at a novel, something he hadn’t done before, was a risk.

The story, often told, of how the Shoeless Joe story became a novel is an interesting one. An editorial assistant at an American publisher saw a notice of the story and wrote to Kinsella asking if it was part of a novel or if it could be turned into one. In a moment of humility, Kinsella wrote back to say he would need help expanding his material, and the rest, as they say, is history, or at least a famous novel, a Kevin Costner film, and a lifetime of baseball writing.

The story, often told, of how the Shoeless Joe story became a novel is an interesting one. An editorial assistant at an American publisher saw a notice of the story and wrote to Kinsella asking if it was part of a novel or if it could be turned into one. In a moment of humility, Kinsella wrote back to say he would need help expanding his material, and the rest, as they say, is history, or at least a famous novel, a Kevin Costner film, and a lifetime of baseball writing.

It wasn’t all baseball, of course. Kinsella had two main sorts of fiction: his idyllic, magical realist baseball writing and then some satirical social commentary in a series of story collections about Indigenous people living on the imaginary Hobbema reserve. The Hobbema stories provoked controversy almost from the start about cultural appropriation. Kinsella was not Indigenous himself, and to write from an Indigenous point of view in an Indigenous voice earned him criticism, especially in later years. At first he was praised for his authenticity and for exploring the situation of a marginalized community; also for his humour. But then came the criticism from those who thought he had no right, the stories should be banned, etc.

Steele carefully reproduces both sides of the debate and, a bit frustratingly, does not take sides. But then he doesn’t take sides or present his views about anything. The second half of the biography shifts from disguised autobiography to annotated bibliography: we get a record of all the stories and novels Kinsella wrote and learn that this reviewer praised them while that one said he was repeating himself, that one reviewer thought he was in the same league as Garcia Marquez while another thought his magical realism was more at the level of The Twilight Zone.

What does Steele think? He did a doctoral dissertation on Kinsella’s stories, but he is surprisingly mute here. There is little analysis, except at the very end, where he tells us that one of the themes of Kinsella’s work is the mending of relationships, which would make sense, given what we learn from the biography about Kinsella’s relationships, which were often broken. He had a distant relationship with his father, went through three failed marriages and several other unsuccessful romances, and he was always the loner, the shy little boy growing up on an isolated farm in rural Alberta who didn’t easily make friends and who grew up to be an angry curmudgeon, lashing out at his country, his university, his neighbours, his students, everyone.

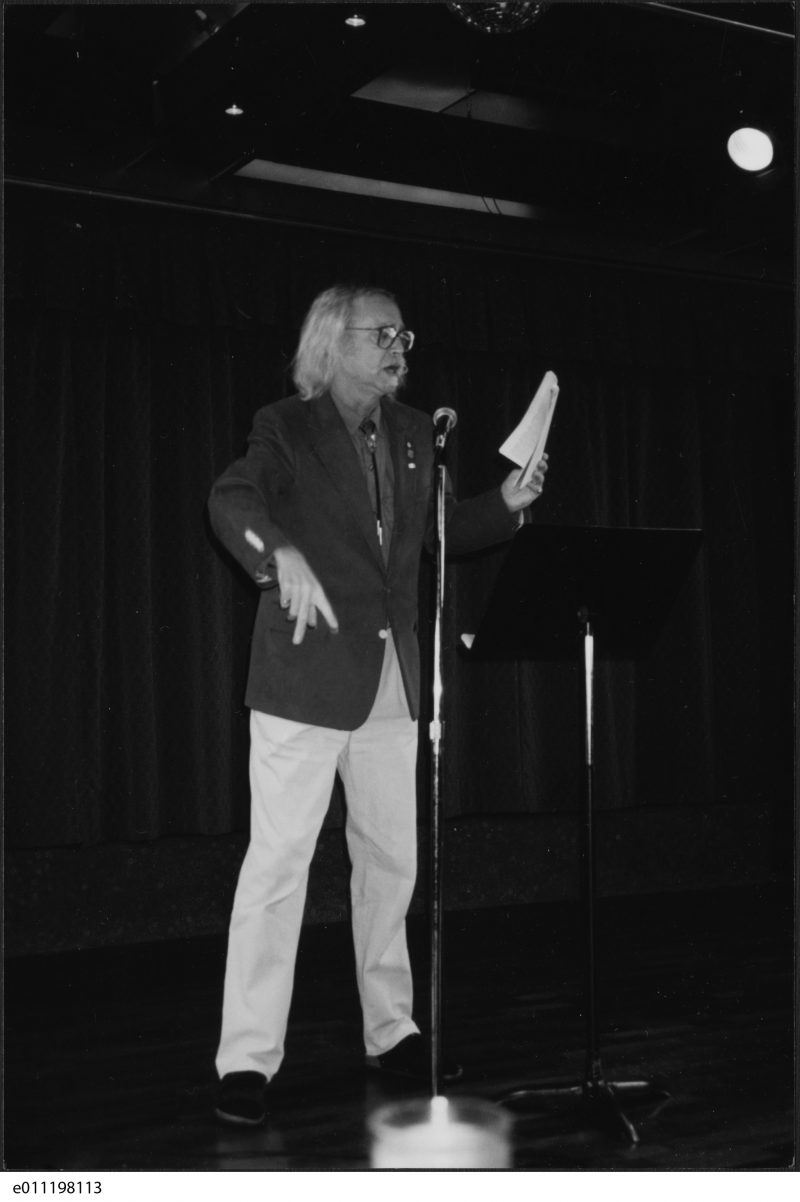

Sometimes he did this amusingly, as when he criticized the attendees at a book reading as having all the animation of parking meters. Sometimes he just seemed angry, as when his response to recognition in the 1980’s was to say it was about f—ing time and it should have happened twenty years before.

He seems to have been an unhappy and insecure man. Steele notes that Kinsella felt looked down on at the University of Calgary for being a mere writer rather than an academic, and also provides plenty of evidence that Kinsella looked down on others (for instance, his “bonehead students,” fifty percent of whom were “functionally illiterate”). One might see a connection here, though Steele doesn’t.

Kinsella’s approach to performance-theatre. At one event he chastised the audience for being as dull as parking meters.

One might also see a connection between Kinsella’s lifelong opposition to authority, his semi-anarchist, anti-elitist, populist approach, and the fact that he wrote so many stories about Indigenous people outwitting the authorities. Again, this is not something Steele explores.

One would have liked more exploration of this sort, some analysis of the stories connecting them to Kinsella’s life. Were the Indigenous stories just his way of lashing out at the world? Were his baseball stories his way of imagining a better life? And why did he write baseball stories in the first place? Or Indigenous stories? How did he choose these subjects, this non-Indigenous writer growing up in the land of hockey?

At one point Steele says Kinsella was influenced by the American writer Richard Brautigan and even wrote a series of stories he called Brautigans. Exploring the nature of that influence might have been interesting. Ditto for exploring the change in Kinsella’s style over the years, which Steele says is revealed in The Essential W.P. Kinsella, a collection published in 2015, just a year before Kinsella died.

There is so much more that could be explored and teased out in the life of this curmudgeonly non-Canadian Canadian. Someone might even find out why his father went to join the American army in 1914, but it will have to be some other biography.

*

Sheldon Goldfarb is the author of The Hundred-Year Trek: A History of Student Life at UBC. He has been the archivist for the UBC student society (the AMS) for more than twenty years and has also written a murder mystery and two academic books on the Victorian author William Makepeace Thackeray. The murder mystery, Remember, Remember, was nominated for an Arthur Ellis crime writing award in 2005. Originally from Montreal, he has a history degree from McGill University, a master’s degree in English from the University of Manitoba, and graduate degrees in English and archival studies from the University of British Columbia.

*

The Ormsby Review. More Books. More Reviews. More Often.

Reviews Editor: Richard Mackie

Reviews Publisher/Designer: Alan Twigg

The Ormsby Review is a journal service for serious coverage of B.C. books and authors, hosted by Simon Fraser University. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Robin Fisher, Cole Harris, Wade Davis, Hugh Johnston, Patricia Roy, David Stouck, and Graeme Wynn. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. As of September, 2018, Provincial Government Patron: Creative BC

Leave a Reply