Al Purdy’s deathbed drama

March 01st, 2016

Al Purdy, twice winner of the Governor General’s Award for poetry and a member of the Order of Canada, died at his home in Sidney, B.C. in 2000.

Aged 80 at the time, he was long thought to have succumbed to the effects of advanced lung cancer.

Now those close to the late literary icon have revealed that Purdy, famous for his poems about wild grape wine and beer parlour brawls, did not wait for the last call.

According to his publisher, Howard White, Purdy engaged the services of right-to-die activists to end his life in the late stages of his terminal illness.

“Al was a free thinker who lived his life the way he wanted and wanted to end it on his own terms too,” says White. “But he only beat the grim reaper by a few days. His death certificate listed his death as natural because it had been expected at any time.”

The news is reminiscent of similar revelations about Purdy’s fellow literary icon and close friend, the novelist Margaret Laurence, who was long thought to have died of lung cancer in 1987, but was later revealed to have ended her own life in the late stages of the disease.

Purdy was a strong supporter of the right-to-die movement but chose to keep the circumstances of his passing confidential to avoid subjecting his grieving family to unwanted publicity.

Purdy’s friends have chosen to break silence now because John Hofsess, the man who assisted Purdy, left a sensational account of his life as a vigilante euthanasiast to be published in Toronto Life following his own assisted suicide on February 29, 2016.

In his version, Hofsess cast himself in a heroic role trying to relieve a great writer of his suffering and portrayed the poet’s wife Eurithe as an obstructing figure.

In fact, Eurithe Purdy was herself a member of the Right to Die Society and a supporter of assisted death. Mr. and Mrs. Purdy, who were married for 39 years, agreed to prolong Purdy’s life until final stages of his cancer by mutual consent.

Although Mrs. Purdy, now 91, confirmed the facts of her husband’s passing, she has stated she will make no further comment.

The in-depth article by the late John Hofsess can be accessed via:

http://torontolife.com/city/life/john-hofsess-assisted-suicide/

[BookLook home page photo of Al Purdy by David Boswell, during a 1978 interview conducted by Alan Twigg]

*

MORE INFORMATION ABOUT AL PURDY, ALL FROM ABCBOOKWORLD

Like Pauline Johnson who also came to die on the West Coast, Purdy was welcomed as a writer in British Columbia, but his career was more deeply connected to Ontario.

Al Purdy was one of Canada’s premier poets, an enigmatic man who combined his highly developed sensitivity to natural word rhythms with an engaging frankness to produce poems of lasting beauty, sardonic humour and reflective depth. Purdy’s public persona was that of a non-university-educated cynic with rolled-up sleeves, homemade grape wine and a difficult-to-live-with wife. The Hallelujah-I’m-a-Bum buoyancy of his poetry readings contributed to his irascible raconteur appeal. Underneath the demeanor of an obstinate, self-confessed born loser lurked, according to Purdy, was an obstinate, self-confessed born loser. His apparently colloquial style influenced many other poets, particular Peter Trower. Even though Purdy liked to roll up his sleeves and snarl, he was a great deal more bookish and contrived than he appeared. He corresponded extensively with writers and critics. Purdy was intensively concerned with poetry politicking on an informal level to an extent that some antiquarian booksellers have jokingly suggested an unsigned copy of an Al Purdy book should be worth more than a signed copy.

Al Purdy was born December 30, 1918, in Wooler, Ontario, two-and-a-half months after the munitions dump exploded in Trenton, Ontario. This event known as the great Trenton disaster was later incorporated into his coming-of-age novel set in 1918. He lived in Trenton from age two until he joined the Canadian Air Force. Purdy lived throughout Canada as he developed his reputation as a gruff but sophisticated brewer of homemade beer. His collections included two winners of the Governor General’s Award, Cariboo Horses (1965) and Collected Poems (1986), and other classics such as Poems for All the Annettes, In Search of Owen Roblin and Piling Blood. Later in life he travelled widely with his wife Eurithe and settled in Ameliasburg, Ontario and Sidney, B.C. His wife was integral partner who managed his finances shrewdly. In addition to his 33 books of poetry, Purdy published one novel, A Splinter in the Heart, an autobiography and nine collections of essays and correspondence. He was appointed to the Order of Canada in 1983 and the Order of Ontario in 1987. As an autodidact, he had a special friendship and corresondence with George Woodcock, who bequeathed money in his will for Purdy to hold a wake. It was never held. Purdy also had an enduring correspondence with Margaret Laurence and many other Canadian writers, some of whom he courted in order to advance his career, and some of whom courted him. George Galt edited a collection of Purdy’s correspondence. Al Purdy died at Sidney, B.C. April 21, 2000. More than 300 people turned up at Alix Goolden Hall in Victoria for a group reading to honour the late Al Purdy in conjunction with the release of his collected poems, edited by Sam Solecki, called Beyond Remembering (Harbour). Among the readers were P..K. Page, Phyllis Webb, Lorna Crozier, Pat Lane, Gary Geddes, Jay Ruzesky, Carla Funk, Sheila Munro and Patricia Young. Al Purdy’s ashes are buried in Ameliasburg at the end of Purdy Lane.

BOOKS:

The Enchanted Echo (1944)

Pressed on Sand (1955)

Emu, Remember! (1956)

The Crafte So Long to Lerne (1959)

The Blur in Between: Poems 1960-61 (1962)

Poems for All the Annettes (1962)

The Cariboo Horses (1965)

North of Summer: Poems from Baffin Island (1967)

Wild Grape Wine (1968)

Love in a Burning Building (1970)

The Quest for Ouzo (1971)

Hiroshima Poems (1972)

Selected Poems (1972)

On the Bearpaw Sea (1973)

Sex and Death (1973)

In Search of Owen Roblin (1974)

The Poems of Al Purdy: A New Canadian Library Selection (1976)

Sundance at Dusk (1976)

A Handful of Earth (1977)

At Marsport Drugstore (1977)

Moths in the Iron Curtain (1977)

No Second Spring (1977)

Being Alive: Poems 1958-78 (1978)

The Stone Bird (1981)

Birdwatching at the Equator: The Galapagos Islands (1982)

Bursting into Song: An Al Purdy Omnibus (1982)

Piling Blood (1984)

The Collected Poems of Al Purdy (1986)

The Woman on the Shore (1990)

Naked With Summer in Your Mouth (1994)

Rooms for Rent in the Outer Planets: Selected Poems (1996)

To Paris Never Again (1997)

Beyond Remembering: The Collected Poems of Al Purdy (2000)

Beyond Remembering: The Collected Poems of Al Purdy (2000)

Rooms for Rent in the Outer Planets: Selected Poems 1962–1996 (Harbour Publishing 1996).

Other:

No Other Country (prose, 1977)

The Bukowski/Purdy Letters 1964 – 1974: A Decade of Dialogue (with Charles Bukowski, 1983)

Morning and It’s Summer: A Memoir (1983)

The George Woodcock/Al Purdy Letters (edited by George Galt, 1987)

A Splinter in the Heart (novel, 1990, 2000)

Cougar Hunter (essay on Roderick Haig-Brown, 1993)

Margaret Laurence – Al Purdy: A Friendship in Letters (1993)

Reaching for the Beaufort Sea: An Autobiography (1993)

Starting from Ameliasburgh: The Collected Prose of Al Purdy (1995)

No One Else is Lawrence! (with Doug Beardsley, 1998)

The Man Who Outlived Himself (with Doug Beardsley, 1999)

Yours, Al: The Collected Letters of Al Purdy (Harbour, 2004). Edited by Sam Solecki.

Editor:

The New Romans: Candid Canadian Opinions of the US (1968)

Fifteen Winds: A Selection of Modern Canadian Poems (1969)

Milton Acorn, I’ve Tasted My Blood: Poems 1956-1968 (1969)

Storm Warning: The New Canadian Poets (1971)

Storm Warning 2: The New Canadian Poets (1976)

Andrew Suknaski, Wood Mountain Poems (1976)

ALSO:

Budde, Robert, editor. The More Easily Kept Illusions: The Poetry of Al Purdy (Wilfrid Laurier University Press, 2006). $14.95 0-88920-490-X.

[BCBW 2006]

When Al Purdy was diagnosed as having a tumour on his lung, unlike many people in his predicament he didn’t refuse to talk about it. His friends coped by trying to be brave. Some wrote poetry, some sent flowers. Poet Patrick Lane obsessively baked bread—more than Al and his wife Eurithe could possibly eat. “Why don’t you hurry up and die so I can stop baking!” Patrick asked Al.

Each time Susan Musgrave visited the Purdy’s house on Lochside Drive, on the outskirts of Sidney, Al Purdy asked her if, when the time came, she would like some of his ashes. Each time she squirmed, it being hard to imagine someone who took up so much psychic and physical space being reduced to ashes. The last time she visited he asked if she wanted any part of his remains. “Which part, Al?” she asked. Eurithe was in the room. “My penis,” Al replied. Susan Musgrave says she wouldn’t have expected less.

With many references to Purdy’s own work, the following commemorative poem by BCBW columnist Musgrave was read to Al Purdy before he died on April 21—and he liked it.

Smuggle them to Paris and fling them

into the Seine. P.S. He was wrong

when he wrote, “To Paris Never Again”

Put them in an egg-timer – that way

he can go on being useful, at least

for three minutes at a time

(pulverize him first, in a blender)

Like his no good ’48 Pontiac

refusing to turn over in below zero weather,

let the wreckers haul his ashes away

Or stash them in the trunk of your car:

when you’re stuck in deep snow sprinkle them

under your bald tires for traction

Mix them with twenty tons of concrete,

like Lawrence at Taos, erect

a permanent monument to his banned

poetry in Fenelon Falls

Shout “these ashes oughta be worth some beer!”

in the tavern at the Quinte Hotel, and wait

for a bottomless glass with yellow flowers in it

to appear

Mix one part ashes to three parts

homemade beer in a crock

under the table,

stir with a broom, and consume

in excessive moderation

Fertilize the dwarf trees at the

Arctic Circle

so that one day they might

grow to be

as tall as he, always the first

to know when it was raining

Scatter them at Roblin’s Mills

to shimmer among the pollen

or out over Roblin Lake

where the great *boing* they make

will arouse summer cottagers

Place them beside your bed where they can

watch you make love, vulgarly

and immensely, in the little time left

Stitch them in the hem of your summer dress

where his weight will keep it

from flying up in the wind, exposing

everything: he would like that

Let them harden, the way the heart must harden

as the might lessens, then lob them

at the slimy, drivelling, snivelling,

palsied, pulseless lot of critics who ever uttered

a single derogatory phrase in anti-praise

of his poetry

Award them the Nobel Prize

for humility

Administer them as a dietary supplement

to existential Eskimo dogs with a preference

for violet toilet paper and violent

appetites for human excrement: dogs

that made him pray daily

for constipation in Pangnirtung

Bequeath them to Margaret Atwood,

casually inserted between the covers

of Wm Barrett’s IRRATIONAL MAN

Lose them where the ghosts of his Cariboo

horses graze on, when you stop to buy oranges

from the corner grocer at 100 Mile House

Distribute them from a hang-glider

over the Galapagos Islands

where blue-footed boobies will shield him

from over-exposure to ultraviolet rays

Offer them as a tip to the shoeshine boys

on the Avenida Juarez, all twenty of them

who once shined his shoes for one peso

and 20 centavos – 9 and a half cents –

years ago when 9 and a half cents

was worth twice that amount

Encapsulate them in the ruins of Quintana Roo

under the green eyes of quetzals, Tulum parrots,

and the blue, unappeasable sky –

that 600 years later they may still be warm

Declare them culturally modified property

and have them preserved for posterity

in the Museum of Modern Man, and, as

he would be the first to add, Modern Wife

As a last resort auction them off

to the highest bidder, the archives

at Queens or Cornell where

Auden’s tarry lungs wheeze on

next to the decomposed kidneys of Dylan Thomas;

this will ensure Al’s survival in Academia, also

But on no account cast his ashes to the wind:

they will blow back in your face as if to say

he is, in some form, poetic or other, here

to stay, with sestinas still to write

and articles to rewrite

for The Imperial Oil Review

No, give these mortal remains away

that they be used as a mojo to end the dirty

cleansing in Kosovo, taken as a cure

for depression in Namu, B.C., for defeat

in the country north of Belleville, for poverty

hopping a boxcar west out of Winnipeg

all the way to Vancouver, for heroin addiction

in Vancouver; a cure for loneliness

in North Saanich, for love in Oaxaca,

courtship in Cuernavaca, adultery

in Ameliasburgh, the one sure cure

for extremely deep hopelessness

in the Eternal City, for death, everywhere,

pressed in a letter sent whispering to you

By Susan Musgrave

[Al Purdy was born in 1918 in Wooler, Ontario. A memorial gathering was held in Sidney on April 30th.]

[BCBW SUMMER 2000]

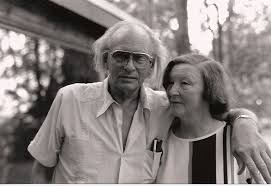

Al claims Eurithe lied about her age when they eloped in 1941. She says not, that she was legal—nearly seventeen, a mature girl from a big family. He likes to think of himself as a cradle robber; it goes with the rogue poet persona.

It is her pragmatic, no-nonsense, non-fiction approach that has kept the two of them on track for over fifty years. It is Eurithe who has balanced the books and steered through some pretty rough terrain, not excluding those irritating and time-consuming poetry wannabes who sometimes tie themselves to the fast track of the famous.

Her unusual name and unorthodox life are matched by a face in a million. Eurithe has the inscrutable beauty of a woman who has lived for a thousand years, most of them spent in the humid environment of talking men.

She is that interesting anomaly, the artist’s wife, simultaneously muse and servant to the muse. Al would not be Al as we know him without her. She is the one who has taken the small earnings and made them into a comfortable life. She is the one at the centre of many great poems. If she is not the direct inspiration, then she is the listener, his best. When the “F” word, fame, is spoken, she knows it is theirs, a mutual achievement. “We” is the matrix in which language is transformed into beauty.

When asked what has kept them together for fifty-seven years, he is quick to exclaim “Love!” while she looks somewhat skeptical.

While her husband wrote and sometimes held down a job, Eurithe steadily toiled as teacher and secretary. She took the grant and prize money and invested it in real estate.

As the second eldest in an Ontario family of eleven children, all of whom are hard workers and achievers, she has earned her comfort.

Eurithe makes a great pie and is still struggling to create the perfect loaf of bread. The first time I tried to show her, at Roblin Lake in the A-frame they built and where Al has written many beautiful poems, she put the rising bread into the oven in the plastic bowl I was using for mixing, while I was having my morning swim in the lake. The result was great sculpture but inedible. The second time, when I gave her a lesson with the poet Lorna Crozier, we left out the salt and the fat in deference to Eurithe’s tired heart and the poet complained, excoriating me for undermining the bread for female territorial reasons!

Eurithe has either learned or knew intuitively that throwing her lot in with the great ego of a great voice was a lot like making bread. It has to do with hot air rising.

One baby in many, she made the decision many offspring from large families make and had only one herself. Eurithe says that most of her maternal energy has been consumed by the poet and the poetry she has fed in the literal and figurative sense. It is as if she has given herself to history.

There was a time when Eurithe wanted to be a doctor, but the life in poetry made no room for that.

When Eurithe abandons her silence, it is usually when her son is the issue or the rights of women, both subjects she takes very seriously.

I asked her once… if she found it paradoxical that she was so strong on the rights of women and so willing to lie down for poetry, leaving her own dreams in a drawer. She responded that she and Al are both devoted to the same god and her autonomy rests in that.

Eurithe is not a conventional woman of her age. She is a sexual being in her eighth decade. The sparks fly between them. You have the sense the irritable romance will proceed as long as both of them breathe.

At yard sales, he lurks rare books while she sniffs out china, especially her favourite with the green edge. Together they have shopped the global village, admiring its antiquities.

There is an awareness that, for Al and Eurithe, freedom is guarded contraband. Pulses are taken. Fat is cut. Poems run through the hourglass. They do not exchange presents on birthdays and at Christmas.

Death is respected as the moment the symbolic relationship that produces poetry will pass into history. Eurithe knows she is one of those rare women who have been immortalized.

She does not react when the poet announces to a crowded audience, there in part because every reading might be his last, that he and his bride no longer buy green bananas or play long-playing records. It is only theatre and she has had a lifetime of that. Theatre is fugitive. Poetry is forever.

[Linda Rogers / BCBW 1999]

AL PURDY was born at Wooler, Ontario in 1918. He grew up in Trenton, Ontario, rode the freights to the West Coast, and took mainly working class jobs as he evolved his poetry of engaging frankness, sardonic humour and reflective depth. Some of his many poetry books are Poems for All the Annettes (1962), Cariboo Horses (1965), for which he received the Governor General’s Award, A Handful of Earth (1977), an anthology Being Alive (1978) and The Stone Bird (1981). He has travelled extensively. Al Purdy lives in Ameliasburg, Ontario. He was interviewed in 1978.

T: What was your family upbringing like?

PURDY: We were lower middle class, I guess you’d call it. My father was a farmer who died of cancer when I was two. My mother moved to town and devoted her life to going to church and bringing me up. I suppose I reacted against religion. But I remember when I rode the freight trains west for the first time, when I was sixteen or seventeen, I got lost in the woods and couldn’t get out. So I prayed. I wasn’t going to take any chances, no chances at all.

T: If a person reacts that way when he’s very young, they say he’ll react that way again when he’s old.

PURDY: Christ, I’ll never make it! I haven’t prayed since that time. I doubt if I ever will again. I’m not religious in any formal sense, not in any God sense.

T: Do you think riding the freights appealed to you because it put you in touch with your survival juices?

PURDY: Well, let me give you the story about the first trip I took. I was hitchhiking north of Sault Ste. Marie when suddenly the Trans-Canada Highway didn’t go any further. So I had to catch a train. I waited till after midnight. I got onto a flatcar that had had coal on it. It was raining and so I huddled there, all self-equipped with two tubes of shaving cream and an extra pair of shoes and a waterproof jacket.

We went all night into a town called Hawk Junction. I was desperate from the rain. I got out my big hunting knife and tried to get into one of the boxcars. I ripped the seal off one of the cars and tried to open the door but I couldn’t do it. So I went back and huddled miserably on the flatcar. I didn’t know I was at a divisional point. A cop came along and said, “You can get two years for this.” He locked me up in a caboose with bars on the

windows. There was a padlock on the outside of the door, which opened inward. Then he came along a couple of hours later and took me home to have lunch with his family. They gave me a Ladies’ Home Journal to read.

I began to get alarmed. What will my mother think? Two years in jail. The window of the caboose was broken where other people had tried to get out and couldn’t do it. But I noticed, as I said, that the door opened inward. There was a padlock and a hasp on the outside. I put my feet up on the upper part of the sill and got my fingers in the hasp. I pulled the screws out of the padlock on the outside.

I started to walk back to Sault Ste. Marie, which was a hundred and sixty-five miles. Then I got panicky. They’ll follow me. I’m a desperate criminal. I broke a seal. So I thought I’d walk a little way in the woods so they won’t see me. But I got in too far. I couldn’t get out. I was there for two bloody days. It rained. That was the last time I prayed, as I said.

T: What were your ambitions as a kid?

PURDY: To stay alive. To get along with other kids. Growing up in a small town, the only son of a very religious woman, I was always alone. Until I got into the Air Force at the age of twenty or so, I didn’t get along with anybody. I became a great reader. I read all the crappy things that kids read. I remember there was a series of paperback books back then called the Frank Merriwell series. When I was about thirteen, a neighbour moved away and gave me two hundred copies of Frank Merriwell. This guy Frank Merriwell went to Yale University and he won at everything he didnaturally he was an American and anyway, he went through many vicissitudes. I pretended I was ill and went to bed. My mother fed me ice cream and I read all two hundred books. I stayed in bed for two months. Then I went back to school and passed into the next form.

T: Were you good in school?

PURDY: Not really. I even failed one year so I could play football. One year I got ninety percent or something and the next year I got forty. Don’t ask me why. I started writing when I was about thirteen. I thought it was great when in fact it was crap. But you need that ego to write. Always.

T: You sound like you were probably pretty harem-scarem in those days.

PURDY: No, I wasn’t harem-scarem at all. I was pretty conventional. Also I was always very discontented. A miserable little kid. I started, out of sheer desperation, to ride the freight trains. There’s a quality of desperation about riding the freights. In my own mind, I was sort of a desperate kid. At a certain age you’re always uncertain how other people will take you. I was desperately unhappy trying to adjust to the world. Finally I didn’t give a damn.

T: Was the RCAF the next step in your life, after the freight trains?

PURDY: I was doing odd jobs around Trenton. What you did was you picked apples or you worked for Bata shoes. You quit one and then the other. I got into the Air Force for a job. I was there six years. I took a course and became a corporal, then an acting sergeant. Then I was demoted from acting sergeant to corporal and all the way down.

T: You got demoted “to the point where I finally saluted civilians.” Why?

PURDY: By this time I was…going out with girls. I’d been too scared to go out with them up to the age I got into the Air Force. Once, when I was corporal of the guard, I drove the patrol car over to Belleville to see this girl after midnight. I got caught at it. I was acting sergeant at Picton where I had a big crew of Americans waiting to get into training. What I did was appoint a whole bunch of acting noncoms so that I would have plenty of freedom. I went out on the town again. Actually I was enjoying myself for the first time in my life. I hated the town of Trenton and I was finally out of it.

T: You’ve described your first book of poetry, The Enchanted Echo, as crap. Did you pay for its publication?

PURDY: Sure. Clarke and Stuart in Vancouver printed it for me. I cost me two hundred dollars to do about five hundred copies. About one hundred and fifty of them got out so I guess about half of those have been destroyed. I went back there ten years ago and they’d thrown them all out. Or they’d burned them. I’d been afraid to go back because I didn’t think I could pay storage charges.

T: Around this time you got married. Your wife plays a pretty integral part in your poetry, yet we never get a clear picture of what kind of person she is. ..

PURDY: Oh, she’s good material. She fixes small television sets and bends iron bars. I picked her up in the streets of Belleville, way back when. Her name’s Eurithe because I think her parents were scared by the Odyssey or Iliad or something. It’s a Greek name. I don’t know why they picked such an oddball name because they’re pretty straight people.

T: Have you ever tried writing a novel?

PURDY: Yes, I got sixteen thousand words once but it was terrible. I used to write plays, too. Ryerson Press accepted a book and the first play I wrote was produced, so my wife and I moved to Montreal so I could reap the rewards for my genius. She went to work to support me, as any well behaved wife should. It turned out I had to write a dozen plays before I could get one accepted by the hardboiled CBC producers. She decided if I could get away with not working, she could too. She quit her job, though I advised her against it. That’s when we built the house, which would be in ah. ..oh hell, ’57 or something like that.

T: Were those the good ol’ days or the bad ol’ days?

PURDY: Oh, the bad old days. We were so broke! We spent all our money buying a pile of used lumber and putting a down payment on this lot. It was very bad for a while. You know how insecure your ego is when you have no money and you’re jobless. There’s nothing more terrible than walking the streets looking for a job. I’d been so sick of working for somebody else. Things were so bad we ate rabbits that neighbours had run over and gave to us because they knew we were broke.

I was picking up unemployment insurance for quite a while. When I built the house, I was still getting it in Montreal. I didn’t dare move the unemployment insurance to Belleville because they’d give me a job. I used to drive to Montreal every two weeks to pick up the unemployment insurance. I’d drive like hell. Finally I had to get a job. So I decided to hitch-hike to Montreal. It was twenty below zero. I always pick a day like that. I got seventy miles and I couldn’t make it any further. I had no gloves and I was freezing to death. Finally I got so disgusted I hitch-hiked back again. Things like that always happen. Born loser.

T: Isn’t it possible to perpetuate that “born loser” image yourself?

PURDY: Oh, sure. It’s your own attitude. Now I don’t figure I’m going to lose hardly anything. But I used to always have that in the back of my mind, that I was going to lose or be defeated.

T: Is a talent for writing something you’re born with?

PURDY: I had no talent whatsoever. If you look back at that first book, it’s crap. It’s a craft and I changed myself. Mind you, there are qualities of the mind which you have to have. I don’t know what they are.

Still you look at some precocious little bastard like W.H. Auden–who was one of the closest to genius in this century-and you wonder. My God, there’s some beautiful lines, beautiful poems.

T: How did you come to meet Irving Layton and Milton Acorn?

PURDY: I’d been corresponding with Layton because I’d found a couple of his books and liked them. After I got out of working at a mattress factory, I decided to go to Europe. I went to Layton’s place in Montreal and slept on his floor before we caught our boat. I met Dudek through him. I can remember being at this drunken party in Montreal and lying on the floor with Layton, arm-wrestling. Dudek was hovering above us, supercilious and long-nosed, saying, “And these are sensitive poets!”

Milton Acorn had come from Prince Edward Island to sell his carpenter tools. He’d visited Layton. I was writing plays and Layton told Acorn to come around and see me and I’d tell him something about writing plays. I couldn’t tell him anything. I couldn’t even write them myself.

T: What made you head off to the Cariboo when you got your first Canada Council Fellowship in 1960?

PURDY: I was looking for an excuse to do anything. I only got a thousand bucks so I decided to write a verse play. I’d been stationed at Woodcock during the war, which is about a 150 miles from Prince Rupert. Totem poles, Indians and the whole works. We were building an airstrip.

T: So did you intuitively think the Cariboo would stimulate you? Likewise for your trip to Baffin Island?

PURDY: I thought I was so damn lucky to be able to go up there to Baffin Island. I’m the only writer on the whole damned island! The feeling that nobody’d ever written about it before!

T: Now you’ve published twenty-five books, fourteen in the seventies alone. Do you consider yourself prolific?

PURDY: I’m not prolific like Layton. I’ll publish a small book and there’ll maybe be three or four poems which I think are worth including in Being Alive. It’s a frightening thing to look backward and see that the earlier books have more poems in the collection than the later ones.

T: How closely did you work with Dennis Lee in editing Being Alive?

PURDY: He’s a friend of mine. There are about fifteen poems which have been changed a bit because he’d look at a poem and say, “I don’t quite understand this” or “I think this could be a little bit better.” Picking the poems was a mutual thing. The idea was to be able to read through the sections and be able to go on to a new section easily. The divisions are not so clear cut as in Selected Poems.

It’s by far the best book I’ve ever brought out. It amounts to a “collected” but it feels like a gravestone at the end of a road. There’s a feeling of where the hell do I go from here? I certainly write less as I grow older. I’m writing very good poems at infrequent intervals. Like “Lament” and “A Handful of Earth.”

T: Do you ever force yourself to write?

PURDY: Occasionally. I think a prose writer forces it out like toothpaste, but I prefer not to. Sometimes you’ve got a thought and you want to explore it. I dunno. The title poem of The Cariboo Horses was written in about half an hour. Another poem, “Postscript,” took seven years.

T: Ten years ago you said people who develop a special way of writing, like b.p. Nichol or the Tish-Black Mountain people, were going down a dead end. Yet they’re still travelling after a decade.

PURDY: It’s still a dead end. They don’t have any variety. The Black Mountain people talk in a certain manner in which they make underemphasised a virtue. It’s dull writing. It’s far duller than conversation. I can’t understand how people can write it except kids can write it and think, I too can be a poet. They can ignore a thousand years of writing poems, not read what’s come before. There’s so much to read, so much to enjoy. That’s the reason to read poetry, to enjoy it.

T: Do you have any thoughts on the general characteristics of Canadian literature?

PURDY: The most prominent characteristic of Canadian literature is that it’s the only literature about which the interviewer would ask what the characteristics are.

T: I think your best poems are those that cover the eerie meeting place between past and present, such as “Method for Calling Up Ghosts,” “Remains of an Indian Village,” “Roblin’s Mills 1 and 2,” “Lament for the Dorsets.” Do you believe you have a soul?

PURDY: Well, Voltaire had some thoughts on that. He tried weighing himself before and after death. I don’t think he came up with anything. I don’t think I do have a soul. But there are areas in our nature that we don’t know about. It’s possible that we may find something that we haven’t found before and we may use that word that’s already invented and call it a soul. We use that word because it’s the only word we have. You can feel this, of course, this so-called transmigration of souls. I thought it was a fascinating concept to imagine everybody living to leave lines behind on the street where they’ve been in “Method for Calling Up Ghosts.” What it means is you’re walking across the paths of the dead at all times. Every time you cross the St. Lawrence River you’re crossing Champlain’s path.

T: You think a lot about death?

PURDY: Quite a bit.

T: You were born in 1918. Has feminism affected your life at all?

PURDY: Every time I read my poem “Homemade Beer” it affects me. The audience thinks, “male chauvinist.” It’s a bawdy, exaggerated poem. Then I can read “The Horseman of Agawa” and it’s exactly the opposite. People think you want to be one thing. You’re not one thing. You’re everything. Of course women have been second-class citizens for years. To gain a position of near equality, which they certainly haven’t done yet, they’ve got to exaggerate. I exaggerate, too. Those remarks about my wife were facetious, of course, but I’m trying to imply with exaggerations that she’s a tremendously capable woman.

T: In “The Sculptors” you enjoy the imperfections of the broken Eskimo carvings and in “Depression in Namu, BC” you write, “beauty bores me without the slight ache of ugliness.” There seems to be a streak in your that feels affinity with imperfection, that wants things to be blemished.

PURDY: Don’t you ever want to splash muddy water into a sunset? A sunset is so marvellous, how are you going to paint it? How are you going to talk about it? So there is a quality of wishing to muddy up perfection, I agree.

T: You end many of your poems with a dash, as if the poem is not really completed.

PURDY: Yes, a lot of poems are in process, as if things happen after you stop looking at it. A poem is a continual revision, even if you’ve written it down without changing a single word. I like the thought of revision. When I copy a poem, I often change it. When I’ve written a poem in longhand, as I always do, I’ll type, then I’ll scribble it all up with changes.

T: What is there in you that needs to commemorate your existence thorough poetry?

PURDY: You have to back to when you started to write. I think most young poets begin to write through sheer ego. Look at me, no hands, Mom. There’s always going to be the element of ego, because we can’t escape our egos. We don’t necessarily want to. But there has to be a time when we can sit down and write and try to say a thing and the ego isn’t so important. When you are just trying to tell the truth, you’re not trying to write immortal lines that will go reverberating down the centuries. You’re saying what you feel and think and what is important to you.

T: Are you at all optimistic about our future?

PURDY: I’m pessimistic about everything the older I get. We’re going to wade through garbage. We’re going to split up. The Americans are going to take everything, even though they don’t need to, of course, because they have it already. The world is going to explode and we’ll all be dead. Life is awful.

[STRONG VOICES by Alan Twigg (Harbour 1988)] “Interview”

Al Purdy Nominated for Canada Reads!

Rooms for Rent in the Outer Planets: Selected Poems 1962–1996 (Harbour Publishing 1996), by Canada’s favourite poet Al Purdy, is a finalist for CBC Radio’s Canada Reads 2006.

For the first time in its five-year history, Canada Reads, the CBC Radio program that encourages Canadians to join together each year in the reading of a single book, has shortlisted a book of poetry. The book is Rooms for Rent in the Outer Planets, a selection of best hits by the man often called Canada’s greatest poet, the late Al Purdy.

Rooms for Rent in the Outer planets was nominated by the poet and novelist Susan Musgrave, who will defend her choice in head-to-head debate with champions of four competing titles in a marathon debate next April. Leading up to the great debate, the CBC network will undertake intensive promotion of all five shortlisted books, including biographical sketches of the authors and readings from the works. Purdy will also be the subject of a one-hour film on CBC television starring Gordon Pinsent. In past years

Canada Reads has been highly successful at promoting awareness of selected titles, increasing sales by up to 35,000 copies.

Howard White of Harbour Publishing considers the selection of Rooms for Rent in the Outer Planets “an inspired choice,” calling Purdy “Canada’s poet.”

“Anybody can read him, and have a ball doing it,” says White. “I can’t think of a book that would do all Canadians more good to sit down and read at this point in our history. It might save us yet. It’s just too bad Al isn’t here to see this happen. He would have been over the moon and probably would have written a poem to celebrate.”

Rooms for Rent in the Outer Planets comprises three decades’ worth of Purdy’s finest work, including poems from the Governor-General’s Award-winning The Cariboo Horses to Naked with Summer in Your Mouth. Purdy made the selection himself, assisted by Professor Sam Solecki, his biographer and editor of Yours, Al: The Collected Letters of Al Purdy. In these poems, Purdy ponders the remains of a Native village; encounters Fidel Castro in Revolutionary Square; curses a noisy cellmate in the drunk tank; and marvels at the “combination of ballet and murder” known as hockey, all in the author’s inimitable man-on-the-street style.

Al Purdy was born December 30, 1918, in Wooler, Ontario and died in Sidney, BC, April 21, 2000. Raised in Trenton, Ontario, he spent his life criss-crossing the nation as he developed his reputation as one of Canada’s greatest writers. He twice won Canada’s most prestigious poetry prize, the Governor General’s Award, first for Cariboo Horses (1965) and then for Collected Poems (1986). Later in life he travelled widely with his wife Eurithe while alternating their permanent residence between Ameliasburg, Ontario and Sidney, BC. In addition to thirty-three books of poetry, Purdy wrote a novel, an autobiography and nine collections of essays and correspondence. He was appointed to the Order of Canada in 1983 and the Order of Ontario in 1987. His ashes are buried in Ameliasburg at the end of Purdy Lane.

The four other books on the Canada Reads shortlist are Deafening by Frances Itani (HarperCollins 2003), Cocksure by Mordecai Richler (McClelland & Stewart 1968), Three Day Road by Joseph Boyden (Penguin 2005) and A Complicated Kindness by Miriam Toews (Vintage, Random House 2004). In April 2006, all five panellists will engage in a five-day “battle of the books” and each day, one book will be voted off the list until only the winner remains.

Books by Al Purdy available from Harbour include, in addition to Rooms for Rent in the Outer Planets, Reaching for the Beaufort Sea (1993, autobiography), Starting From Ameliasburgh (1995, essays), No One Else is Lawrence (1998, criticism), To Paris Never Again, (1997, poems), Beyond Remembering (2000, collected poems) and Yours, Al (2004, collected letters). For information on any of these books contact Marisa Alps or Stephanie Sy at Harbour Publishing.

— December 5, 2005, Harbour Publishing.

TORONTO, Canada (March 31, 2006) –

Yours, Al starring Canadian icon Gordon Pinsent, is an evocative film that captures, interprets and celebrates the life and work of one of Canada’s most significant poets and literary geniuses Al Purdy (1918-2000). Actor Gordon Pinsent movingly captures the essence of the poet in this drama set in a metaphorical, abandoned house, which comes to life as Al returns to read, write and remember his favourite poems.

In one of his finest performances Gordon Pinsent gives lifeblood to Al’s words as he steps in to the world of the roving poet who used his natural curiosity to explore people and places that affected him on a daily basis. Purdy wrote about what he knew: work, relationships and this vast country. He rode the rails, worked in factories, and sparred with his muse, all of which is reflected in his timeless poetry and prose and crafted beautifully in this film by director Bill Spahic.

Bill commented, “Al was consumed about what is to be human; to love, to be humiliated, to be triumphant, to fail and that’s what I love about his poetry. He wrote about his inner self and in that process he wrote about all of us.”

Yours, Al captures the eloquence, humility and universality of Al Purdy, taking us through his life, pausing at all its high and low moments, and presents Purdy’s greatest poems, including The Country North of Belleville, At the Quinte Hotel, On Being Human and Necropsy of Love. Those who remember Al Purdy will revel in his words once again, and those new to his work will wonder why it has taken so long to discover him but all will agree that he was indeed ‘the people’s poet’ and ‘the voice of the land.’

Yours, Al by Real to Reel Productions Inc. is a non-chronological exploration of some of Purdy’s favourite themes: relationships and family, love and life, work and country written by acclaimed playwright Dave Carley and director Bill Spahic based on Purdy’s collected works.

Time and place are two important elements in Purdy’s work, and they are equally reflected in the treatment of this film. We see and hear the words of Purdy through a first-person narrative that examines different segments of his life and how these parts are mirrored in his poetry. Throughout the film archival footage and photo stills are layered with dramatic visual interpretations and special effects to convey the depth and emotion of his work.

Above all, it is Pinsent’s riveting performance that pulls it all together.

Yours, Al has been described as “a gift,” “an extraordinary performance, as though Al himself were on screen,” “no better homage to a great poet.”

Producer Anne Pick struggled for six years to raise the modest budget, first pitching it as a documentary then as this drama. She says, “The wait was worth it. As much as I would have been happy with a documentary I’m glad it turned out this way. We were able to bring so much more to the production creatively and Gordon is simply brilliant.”

Added Spahic, “And every single member of the production team entered into the spirit of the project I think with the sense that in working with Purdy and Pinsent, we were dealing with two of Canada’s national treasures. It was more than just a job. We felt we were privileged.”

from City of Toronto

Al Purdy 1918 – 2000

The City of Toronto, through the Toronto Legacy Project, commemorates outstanding individuals in the creative arts. The Toronto Legacy Project was initiated by the City’s first Poet Laureate, Dennis Lee. Toronto’s Poet Laureate Pier Giorgio Di Cicco, and the City of Toronto invite you to attend the unveiling of the Al Purdy memorial statue on:

Tuesday, May 20, 2008

4:30 p.m. to 6:30 p.m.

Remarks: 5:00 p.m.

Queen’s Park North

(east side of Queen’s Park Circle)

This event is a co-operative effort of the City of Toronto, the Toronto Legacy Project and the Friends of the Poet Laureate.

May 20, 20

One of Canada’s most beloved poets was honoured today with the unveiling of a statue in his likeness at an historic ceremony at Queen’s Park. This is only the second full-length statue of a poet in Toronto (the other being of Robbie Burns), and one of very few in Canada. The event was presided over by Toronto’s Poet Laureate Pier Giorgio Di Cicco with Purdy’s widow, Eurithe Purdy, unveiling the monument to her late husband.

Mayor David Miller spoke to the crowd about the man who was often described as Canada’s national poet. “Al Purdy is one of Canada’s greatest poets,” said Toronto Mayor David Miller. “This statue, donated to the people of Toronto by the friends of the Poet Laureate and placed in a prominent location in Queen’s Park, is a fitting tribute to a person who enriched the lives of so many Canadians.”

Mayor David Miller spoke to the crowd about the man who was often described as Canada’s national poet. “Al Purdy is one of Canada’s greatest poets,” said Toronto Mayor David Miller. “This statue, donated to the people of Toronto by the friends of the Poet Laureate and placed in a prominent location in Queen’s Park, is a fitting tribute to a person who enriched the lives of so many Canadians.”

In 2001, Scott Griffin, founder of the Griffin Poetry Prize and a member of the Friends of the Poet Laureate, suggested the statue to Dennis Lee, Toronto’s first Poet Laureate. Together with Lee, Margaret Atwood, Michael Ondaatje and professor Sam Solecki, Griffin commissioned husband and wife sculptors Edwin and Veronica Dam de Nogales to create the memorial artwork after a review of a number of contemporary sculptors.

Lee said of the poet, who died in 2000: “Al Purdy is one of the titans; if we have a national poet in English Canada, he’s it. The Purdy statue is a tremendous way to celebrate his place in our lives.”

Voice of the Land, the name given to the Purdy statue by the Dam de Nogales, is situated prominently in Queen’s Park north.

Griffin – who underwrote the project – along with Lee, Atwood, Ondaatje, and Solecki, partnered with the City of Toronto’s Culture Division to honour Al Purdy with the sculpture. Atwood summarized the importance of the project: “It’s wonderful that the Friends of the Poet Laureate has arranged for this arresting public statue of Al Purdy, one of Canada’s foremost poets. Cities such as Edinburgh, Scotland, are known for their honouring of their own cultural tradition, and it’s encouraging to see Toronto, as well as the province of Ontario beginning to do the same.”

Solecki, Purdy’s editor and close friend, added: “When a great Scottish poet died, one of his friends insisted that ‘Because of his death, this country should observe two minutes of pandemonium.’ Since pandemonium is un-Canadian and not protected by the Charter of Rights, we’re commemorating Al Purdy’s remarkable life with a statue in Queen’s Park.”

Wow! I remember watching the film, and, yes, anything Pinsent is in is brilliant. It’s been good to read this in Booklook and to reread some of Al’s, Susan’s and the Twigg interview. Of course it was the revelation re Purdys death that sparked my interest.

Good for you, Al.