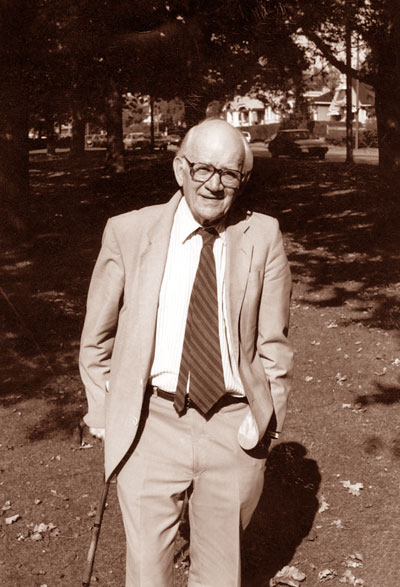

#97 George Woodcock

January 28th, 2016

LOCATION: 6429 McCleery Street, Vancouver

Self-described as “a British Columbian by choice, a Canadian by birth,” the Winnipeg-born, England-educated anarchist George Woodcock was B.C.’s most prodigious man of letters. Here he lived as “a man of free intelligence” from 1959 to 1995 with his wife Ingeborg, raising funds for two charities they founded–Tibetan Refugee Aid Society and Canada India Village Aid–while writing and editing approximately 150 books. Here, as well, Woodcock edited Canadian Literature, the first publication entirely devoted to Canadian books. A friend and biographer of George Orwell, and a friend to the Dalai Lama, Woodcock became the first author to receive Freedom of the City from Vancouver City Council. After their deaths, the Woodcocks’ little house was demolished in order to generate their bequest of almost $2.3 million to the Writers Trust of Canada to support writers in distress.

QUICK ENTRY:

The George Woodcock Lifetime Achievement Award for British Columbia is fittingly named for the anarchist philosopher whose unrivalled productivity was achieved in concert with consistent ideals and humanitarian actions ever since he and Ingeborg Woodcock arrived from London, England, and built a rough cabin at Sooke in 1949.

The Woodcocks remained close friends with the Dalai Lama since they first visited him in Dharamsala, India, in 1961. As the generators of two, still-functioning, non-profit organizations, TRAS [Trans Himalayan Aid Society] and CIVA [Canada India Village Age], the Woodcocks quietly and constructively influenced millions of lives, but never had children of their own and avoided the public spotlight.

During his lifetime, Woodcock was variously described as “quite possibly the most civilized man in Canada”, “by far Canada’s most prolific writer”, “Canada’s Tolstoy”, “a regional, national and international treasure” and “a kind of John Stuart Mill of dedication to intellectual excellence and the cause of human liberty.” Woodcock’s oft-reprinted Anarchism: A History of Libertarian Ideas and Movements (1962) demystifies anarchism and views it as constructive philosophy; a biography of his dear but difficult friend George Orwell, The Crystal Spirit (1966), will also long remain in print.

George Woodcock (left) with Mulk Raj Anand, George Orwell, William Empson, Herbert Read and Edmund Blunden, 1942

Of the approximately 150 books written or edited by George Woodcock, the most vital for B.C. was his collaboration with Ivan Avakumovic for The Doukhobors (1968). Its sobriety and perceptivity obviated the sensationalism of Simma Holt’s cynically packaged Terror in the Name of God (1964), the cover of which featured a large, naked woman outside a burning building and excluded its interior subtitle The Story of the Sons of Freedom Doukhobors. This omission enhanced the misconception that all Doukhobors were unruly nudists and troublemakers. The agrarian, pacifist sect was so relieved to finally have their story told with some depth of understanding that Woodcock was offered a permanent place of residence in the Kootenays if he wished to live among them. He declined.

Born in Winnipeg in 1912, George Woodcock once wrote, “I began even as a boy to realize how wide the world can be for a man of free intelligence.” True to his word, he operated as a man of free intelligence, living underground during World War II in London and later fracturing relations with the University of British Columbia, where he had been the founding editor of Canadian Literature, in order to assert his independence. Woodcock commonly published several new books per year, on a wide variety of subjects, until his death in 1995. He once described himself once as a British Columbian first, and a Canadian second.

George Woodcock’s books pertaining to British Columbia are Ravens and Prophets (1952), The Doukhobors (1968), Victoria (1971), Amor De Cosmos: Journalist and Reformer (1975), Peoples of the Coast: The Indians of the Pacific Northwest (1977), A Picture History of British Columbia (1980), British Columbia: A Celebration (1983), The University of British Columbia: A Souvenir (1986) and British Columbia: A History of the Province (1990).

An e-book of George Woodcock’s editorials for Canadian Literature has been published via UBC, with Alan Twigg’s introduction, “In Praise of an Omnivorous Intelligence. Compiled and edited by Glenn Deer and Matthew Gruman, George Woodcock: Collected Editorials from Canadian Literature also includes Glenn Deer’s “Alive to Unfashionable Possibilities: Reading Woodcock’s Collected Editorials,” written specifically for this edition. http://canlit.ca/woodcock/ebook

FULL ENTRY:

A Man of Free Intelligence: An Introduction to the World of George Woodcock by Alan Twigg

The following summary serves as a concise introduction to George Woodcock’s wide-ranging career as a public intellectual. Further down the page you can find an interview/conversation that occurred between Alan Twigg and George Woodcock, founding editor of Canadian Literature, in 1994, based on talks for the making of the documentary film George Woodcock: Anarchist of Cherry Street. FOR A COMPLETE BIBLIOGRAPHY LISTING MORE THAN 150 TITLES, SCROLL TO THE BOTTOM OF THIS ENTRY.

***

“I began even as a boy to realize how wide the world can be for a man of free intelligence.” – G.W.

George Woodcock’s father Arthur Woodcock was a music-oriented second son and would-be writer who rebelled against his conservative, Shropshire coal merchant father to pursue the arts. Rejecting an offer of partnership in the family coal business, he left for Canada in 1907, via Liverpool and New York, and took a train from Montreal to Manitoba. In Winnipeg he met the vaudevillian Charlie Chaplin and took various jobs, eventually becoming a bookkeeper/accountant for the Canadian Northern railway. Obliged to send for his betrothed, Margaret Gertrude Lewis, a dour milliner’s apprentice, he married her in May of 1911 but the union was never happy. When their only child was born on May 8, 1912, in Winnipeg’s Grace Hospital, she disallowed her husband’s inclination to call the boy George Meredith Woodcock, in honour of one of his favourite novelists, and so for the rest of his life George Woodcock would enjoy carrying an invisible middle name, one that connected him to the spirit of his adventurous father, and distanced him from his undemonstrative mother. “I suppose I am a man who psychic arrangement is Jungian rather than Freudian,” he once wrote. “I loved my father and always disliked my mother.”

One Manitoba winter on Portage Avenue was one too many for Margaret Woodcock who took their only child back to England in the spring of 1913, but it would be sufficient for George Woodcock to one day leave England—as his father had done—to claim his Canadian birthright. After Arthur Woodcock acquiesced to his father’s offer of a junior partnership and dutifully reunited with his family in England, he led a mostly dreary and sickly existence. Prior to his death of Bright’s disease at age 44 in 1926, he instilled in his sympathetic son a shared dream of going further west in Canada. “An extrovert who turned inward with misfortune is how I see him,” George Woodcock wrote. The son not only revered the father; George Woodcock was inspired to succeed in Canada to recompense his father’s failures and dashed ambitions.

Small wonder George Woodcock could write so knowingly about Thomas Hardy’s Wessex for his introduction to a Penguin edition of Return of the Native. Woodcock fully comprehended the hereditary weight of sorrow, of disappointment, of class consciousness, of stilted emotions, jilted love and stunted ambitions. The plight of Arthur Woodcock was Hardyesque, both noble and pathetic.

George Woodcock was raised in various Shropshire and Thames Valley towns within a literate, impoverished family. At school he was particularly averse to sports. The Depression prevented him from continuing his formal schooling as he would have liked. George Woodcock ended his formal schooling in 1928. His coal merchant grandfather offered to pay his tuition for Cambridge on the one condition that he would become an Anglican clergyman. Like his father before him, Woodcock rejected his grandfather’s coercive assistance. Instead he became mired for eleven unhappy years in a futureless job for Great Western Railway as a clerk at Paddington Station, a prisoner of timetables, like his father before him.

If there was a turning point in George Woodcock’s life, other than returning to Canada, it was reading William Morris’ socialist writings on the train to and from work. With access to books and anarchist circles afforded to him by a German exile named Charles Lahr, proprietor of Blue Moon Bookshop, Woodcock became a devotee of the British philosopher, Herbert Read, and joined a circle of friendships with young `progressives’ such as George Orwell (Eric Blair), V.S. Pritchett, W.H. Auden, Stephen Spender and Malcolm Muggeridge. He also fraternized and drank with Dylan Thomas and established some lifelong friendships with the likes of Alex Comfort and Julian Symons. All the while he participated in the political ferment of the 1930s by contributing to various literary and anarchist periodicals.

When his mother died in 1940, he inherited 1,398 pounds. That same year he published his first collection of verse, The White Island, and filed for exemption from military service as a conscientious objector and agreed to perform alternative civilian service with the War Agricultural Committee. Deeply influenced by the fate of idealists during the Spanish Civil War, Woodcock was initially assigned to farm labouring in Essex, but his acquiescence to alternate service was soon dissipated. Instead Woodcock used a trust fund established for him by his grandfather to try his hand at making his living as a fulltime writer in London, mainly by establishing and editing NOW (1940-1947), an eclectic mix of anarchist, pacifist and anti-Soviet socialist commentaries. He was also co-editor of War Commentary.

As he endured a precarious and frugal ‘underground’ existence, Woodcock became increasingly infatuated by a beautiful Italian anarchist in London, Marie Louise Berneri, who was married. She was the daughter of a recently martyred Italian anarchist named Camillo Berneri. Marie Louise, her husband and two others were charged with causing disaffection among the troops by denouncing the war effort in print. The offending handbill for which they were arrested was allegedly typed on George Woodcock’s typewriter. His lifelong sympathies for outlaws such the Métis military leader Gabriel Dumont, Gandhi, the Dalai Lama and Gitksan fugitive Simon Gun-an-Noot partially arose from these war-time experiences as a dissident.

After the war George Woodcock married Ingeborg Linzer Roskelly, a like-minded German-born member of the Berneri circle, and obtained a Canadian passport. In 1949, he and ‘Inge’ left behind his uncomfortable niche in the London literary scene in order to emulate Doukhobor pacifists who had sought freedom in Canada. The Doukhobors had been encouraged and subsidized by Tolstoy near the turn of the century. “I realized that the Doukhobours were something more than nudist shovellers of snow when I began to read Tolstoy and Kropotkin,” he later wrote, “who regarded them as admirable peasant radicals and Nature’s anarchists.” More specifically, the Woodcocks were directly influenced to start anew on the West Coast of Canada by a young Canadian anarchist in London, Doug Worthington, and as a boy George Woodcock had been impressed by depictions of Western Canada that he’d found a Frederick Niven novel called The Lost Cabin Mine. Coming to Canada also entailed a revival of his father’s doomed idealism.

As the Woodcocks arrived in Halifax, he had a premonition that something terrible was happening to Marie Louise Berneri. As they rode the CPR train to Victoria, she died at age 31 of a heart attack. Although he was trained only as an intellectual, George Woodcock gamely tried his hand at homesteading near Sooke on Vancouver Island, clearing some land for a market garden and building a small home with Inge. The nearest Doukhobour settlement was at Hilliers, near Parksville. Not suited for subsistence farming, George Woodcock tried to eke out a living by shovelling manure and contributing to CBC and some periodicals. With the crucial assistance of Earle Birney, Woodcock came to Vancouver to lecture at UBC, where he would later teach both English and French literature. He had never attended university in England and liked to refer to himself in late years as an `autodidact’, someone who is self-taught, giving rise to his affinity and correspondence with poet Al Purdy. One night in 1951 Woodcock was at a party when someone passed along the news that George Orwell (Eric Blair) had died. It was a shock. It was as if a bridge had been removed behind them.

In 1952, Woodcock published the first of his many books pertaining to British Columbia, a travelogue called Ravens and Prophets: An Account of Journeys in British Columbia, Alberta and Southern Alaska. He would publish The Doukhobors (with Ivan Avakumovic, 1968), Victoria (with Ingeborg Woodcock, 1971), Amor De Cosmos: Journalist and Reformer (1975), Peoples of the Coast: The Indians of the Pacific Northwest (1977), A Picture History of British Columbia (1980), British Columbia: A Celebration (1983), The University of British Columbia: A Souvenir (1986) and British Columbia: A History of the Province (1990).

In 1955 Woodcock was barred from continuing a teaching job at the University of Washington in Seattle when he was denied an immigration visa due to his connections to a 1944 anarchist pamphlet, Anarchy of Chaos. As an alien who had advocated “opposition to all organized government,” Woodcock was banned from United States entry by the McCarran Act in the wake of McCarthyism. His vigorous lobbying efforts to overturn the decision were to no avail. He was rescued from his predicament with a teaching post from the Extension Department of UBC in January, 1956. That year he increased his affiliations with CBC and befriended the essayist, conservationist and lay magistrate Roderick Haig-Brown of Campbell River. He later wrote, “For Rod strikes me as one of the wisest men I have known, and sometimes, when I have committed some gross verbal irresponsibility, I see his ghost rising to admonish me with a quiet, smiling remark between puffs on the pipe that was rarely away from his mouth.”

In 1959, Woodcock accepted the part-time position of founding editor of Canadian Literature, the first periodical to be entirely devoted to Canadian writing. He did not instigate the publication that he edited until 1977, as is sometimes assumed. Canadian Literature was created largely under the auspices of Roy Daniells, head of the UBC English department. Woodcock’s role would lead to a deep schism with the university many years later when he went to sell his personal papers. UBC took the position that all papers pertaining to Woodcock’s tenure at Canadian Literature were not saleable because they had been derived from his UBC employment. Woodcock had resigned his Associate Professor status in 1963 to concentrate on writing, but the university had retained his services as an independent editor for the publication. Greatly disappointed, Woodcock sold most of his literary papers to Queen’s University in Ontario. Only after his death were some of his books and personal effects, including his typewriter, donated to UBC Special Collections. George Woodcock edited 73 issues of Canadian Literature. W.H. New edited 72 issues after him.

At age 60, Woodcock described himself in the preface to his collection of essays, The Rejection of Politics, “I began as an internationalist anarchist. I have ended, without shedding any of my libertarian principles, as a Canadian patriot, deeply concerned with securing and preserving the independence of my country (which cannot of course be divided from the individual freedom of its inhabitants), and within that country the integrity—physical and aesthetic—of my mountain-shadowed and sea-bitten patria chica on the Pacific Coast.”

Although something of a workhouse-hermit in his later years, Woodcock developed an extensive range of contacts among writers and other artists, particularly visual artists in Vancouver such as Jack Shadbolt, Toni Onley, Gordon Smith, Joe Plaskett, Jack Wise, Pat O’Hara and Roz Marshall. In particular, the Woodcocks were close friends with Jack and Doris Shadbolt. Neither couple had children so they often spent Christmases together. The Shadbolts had provided the Woodcocks with a roof over their heads in Burnaby in the early 1950s.

The Woodcocks also enjoyed an abiding friendship with the Dalai Lama after they had taken it upon themselves to visit the Tibetan leader in Dharamsala shortly after he had fled Tibet in 1959. This liaison arose from a chance and fortuitous meeting with the Dalai Lama’s niece in India. Upon seeing the wretched conditions faced by the fleeing Tibetans in northern India, the Woodcocks created the Tibetan Refugees Aid Society [TRAS], a mainly volunteer-administered, Vancouver-based agency that has continued to provide support for Tibetans outside of Tibet for more than a half-century. Consequently, when Ingeborg Woodcock was ill in the 1990s, the Dalai Lama assigned his personal physician to administer to her needs. The Woodcocks and the Dalai Lama met privately when he visited Vancouver in 1993, and the Dalai Lama was making arrangements to see Ingeborg Woodcock a second time in 2004, prior to her death in December of 2003.

Ingeborg Woodcock, who maintained a Buddhist perspective, was an enormous directional influence on her husband, mainly as a severe-minded compass. Whereas George Woodcock, like every writer, could be fuelled by vanity and ego, she cautioned him to respond to higher purposes. To this end, George Woodcock chose not to vote, believing the world should be managed by non-profit organizations. Together they supervised a writing contest for charity that resulted in the anthology, The Dry Wells of India (1989). Woodcock credited her as being a terrific organizer. Together the Woodcocks pioneered at least two significant and ongoing philanthropic organizations, Canada India Village Aid (CIVA) and the Woodcock Trust, a fund they created in 1989, in conjunction with the Writers Development Trust, in order to supply emergency support to Canadian writers in need. From 1989 to 2003 the ongoing fund paid out $346,000 to 94 authors. The Woodcocks were involved in countless ‘garage sale’ events through the decades to sell excess belongings, particularly books. In 1981, the Woodcocks and a few like-minded individuals and friends also started CIVA to chiefly help build wells in India. All funds raised, including more than $200,000 in royalties from a travel collection edited by Keath Fraser called Bad Trips, are matched by the Canadian government. With as little hierarchical structure as possible, and no paid staff, CIVA continues to effectively and earnestly provide grassroots aid, largely coordinated by Woodcock co-executor Sarah McAlpine, who formerly took classes from Woodcock at UBC. “The Woodcocks are very compassionate towards little people without a voice,” McAlpine told Douglas Todd of the Vancouver Sun.

The major beneficiary of the Woodcocks’ charity is the Toronto-based Writers Development Trust, now simply called The Writers Trust. It administers a little-publicized fund to provide emergency grants to writers in financial distress. By 1998 the Fund had reportedly allocated more than $135,000 to 43 writers in ‘straightened circumstances’, a condition Woodcock understood only too well, both in England and during his brief homesteading stint in Sooke. The Fund reportedly stood to benefit upon the sale of the Woodcock’s property in the fashionable district of Kerrisdale after Ingeborg Woodcock moved into a senior’s care facility. For more than 40 years the Woodcocks had lived in an old Craftsman-style cottage at 6429 McCleery Street, formerly called Cherry Street. Woodcock was particularly fond of an ancient cherry tree in their backyard, likening it to Malcolm Lowry’s relationship with his beloved pier in Deep Cove. The Woodcocks once made arrangements to meet the Lowrys, their cross-town literary counterparts, in a downtown lounge but the authors mostly ignored each other, leaving their wives to manage forced conversation. After Lowry died, Woodcock was not averse to editing a reprint of Malcolm Lowry: The Man and his Work (1971).

To honour George Woodcock in conjunction with his 82nd birthday and the 10th annual B.C. Book Prizes, hosted by Pierre Berton, B.C. BookWorld instigated and coordinated a series of events in 1994. The city conferred ‘Freedom of the City’ to George Woodcock on April, 12, 1994. “Thank goodness for Vancouver,” wrote Mark Abley in the Montreal Gazette, “which has recognized — and none too soon — that it’s home to a regional, national and international treasure.” Greetings were sent by the likes of Julian Symons, Ursula Le Guin, Jan Morris, Timothy Findley, Mel Hurtig, Svend Robinson, the spokesperson for the Doukhobors in Canada and a representative of the Dalai Lama. The B.C. Minister of Culture, Bill Barlee, addressed the B.C. Legislature on May 6th and invited all MLAs to join in recognizing George Woodcock’s achievements. A two-day symposium was held at Simon Fraser University, May 6-7, to examine George Woodcock’s career. The Bau-Xi Art Gallery hosted an exhibit of original art honouring George Woodcock.

More than 1300 people attended a celebratory gathering at the Vancouver Law Courts, on May 7th that included an unprecedented display of 152 different titles bearing George Woodcock’s name, making it one of the largest exhibitions of books by one living author. The Mayor of Vancouver attended and proclaimed George Woodcock Day. In a speech read on his behalf by Margaret Atwood, Woodcock recognized how the climate for literature had changed since his coastal arrival. “When I reached Vancouver at the beginning of the 1950s, one could count on one’s fingers the serious writers here: Earle Birney, Dorothy Livesay, Ethel Wilson, Roderick Haig-Brown, Hubert Evans and a few younger people. There was virtually no publishing going on locally, and the one literary magazine was Alan Crawley’s historic Contemporary Verse. Now, as tonight’s gathering gives witness, there are hundreds and hundreds of writers working west of the Great Divide, there are scores of local publishing houses, large and small, and there are dozens of literary magazines, some of them of national and international importance…I think the conjunction of the literary arts and the concept and practice of freedom is an essential one; in fact, I believe it is the key to my own work, which has always moved between the poles of imagination and liberty.”

CBC Radio’s Peter Gzowski devoted one half-hour of Morningside to the Woodcock celebration on May 11, 1994. Lilia D’Acres and the West Coast Book Prize Society established a fund for donations to help establish a George Woodcock Centre for Arts and Intellectual Freedom in Vancouver. More than $20,000 was raised for the fund by BC BookWorld. When a heritage building couldn’t be obtained for a Woodcock Centre, all monies raised were donated to the University of British Columbia to establish a permanent George Woodcock exhibit and the George Woodcock Canadian Literature and Intellectual Freedom Endowment Fund. In 1992 Macleans magazine recognized George Woodcock as one the country’s ten most significant citizens.

Woodcock remained indefatigable, attempting to realize his long-held ambition to complete a new translation of Swann’s Way, the first volume of Marcel Proust’s Remembrance of Things Past, and also working on a novel. After George Woodcock died at home on January 28, 1995, Ingeborg Woodcock undertook retyping the manuscript of the Proust translation, possibly completing some of it on her own, but it was never published. Woodcock wrote and edited more than 140 books. The exact number has been difficult to determine. Biographer Don Stewart listed “145 freestanding books and pamphlets.” Antiquarian bookseller Don Stewart of Vancouver has compiled the most comprehensive list of Woodcock’s overall work after purchasing Woodcock’s valuable collection of anarchist publications from the estate.

Since the publication of his first collection of poetry, The White Island (1940), George Woodcock remained an unheralded but earnest poet. In the mid-1970s he wrote, “Clearly my eagerness to publish poetry again sprang from a desire to show that the poet who was my first literary persona had not died but was merely sleeping.” His works included The Centre Cannot Hold (London: Routledge, 1943), Selected Poems (Toronto: Clarke, Irwin, 1967), Notes on Visitations: Poems, 1936-1975 (Toronto, Anansi, 1975), Anima, or, Swann Grown Old: a Cycle of Poems (Coatsworth, Ont.: Black Moss P, 1977), The Kestrel, and Other Poems of Past and Present (Sunderland: Ceolfrith P, 1978), The Mountain Rad: Poems (Fredericton, N.B.: Fiddlehead Poetry Books, 1980), Collected Poems (Victoria, B.C.: Sono Nis P, 1983), Tolstoy at Yasnaya Polyana & Other Poems (Kingston, Ont.: Quarry P, 1991) and The Cherry Tree on Cherry Street: and Other Poems (Kingston, Ont.: Quarry P, 1994).

George Woodcock took it as a matter of professional pride that he could write a book on almost any subject that required his services. His omnivorous intelligence led to an invitation from Mel Hurtig in 1974 to edit Hurtig’s then-proposed Canadian Encyclopedia, an invitation that Woodcock relunctantly declined. His first important book was a biography of William Goldwin (1946), followed by the first book-length study of England’s first professional female novelist, The Incomparable Aphra: A Life of Mrs. Aphra Behn (1948). History, travel, biography, literary criticism, politics and poetry were his main subject areas. He was ideologically and temperamentally in favour of writing for small and obscure publications. He once wrote, “The really independent writer, by the very exercise of his function, represents a revolutionary force.” It has proved impossible to trace and compile all the freelance articles he published. He was known to use the pseudonym Anthony Appenzell. For several years he contributed an As I Please column to the Georgia Straight and later served as the poetry columnist for BC BookWorld. George Woodcock once cited his Welsh ancestry and his Taurian astrological status as reasons for being able to operate outside the mainstream for so long, aside from his anarchist principles.

His oft-reprinted Anarchism (1962) remains a standard history of libertarian movements, readable and important for the way Woodcock demystifies anarchism and views it as constructive. Co-authored with fellow UBC professor Ivan Avakumovic, his fair-minded The Doukhobors (1968) is the definitive study of the Doukhobors in Canada. The agrarian sect was so relieved to finally have their story told with some depth of understanding that Woodcock was offered a permanent place of residence in the Kootenays if he wished to live among them. His studies of the 18th century `revolutionist’ William Godwin, Oscar Wilde, Aldous Huxley, Mahatma Gandhi, Pierre-Joseph Proudhon, Aphra Behn, Peter Kropotkin and the Trappist Thomas Merton (who Woodcock never met) are less well-known than his biography of his dear but difficult friend, George Orwell, The Crystal Spirit, that earned him a Governor-General’s Award in 1967. Woodcock liked to say he rejected honours bestowed by governments but he was willing to accept juried awards and grants determined by his peers. In fact, he accepted three Canada Council travel grants (1961, 1963, 1965), a Canada Council Killam Fellowship (1970-71, a Canadian Government Overseas Fellowship (1957-58) and Canada Council Senior Arts Award. He also won a Molson Prize in 1973 and a Canadian Authors Association Award in 1989. He twice won the UBC Medal for Popular Biography (1971, 1975). He enthusiastically accepted Free Man status from the City of Vancouver, linking the roots of the word civitas to the development of freedom.

Preferring not to be known too well, the sometimes prickly George Woodcock published three works of autobiography. The first was Letter to the Past: An Autobiography (1982), mainly about his life in England. It was followed by Beyond the Mountains: An Autobiography (1987) and Walking Through the Valley (1994). George Fetherling, writing under the name Douglas Fetherling, produced the only book-length biography of Woodcock to date, The Gentle Anarchist (Douglas & McIntyre 1998; Subway Books 2003). A CBC-aired half-hour television documentary, George Woodcock: Anarchist of Cherry Street, was made in 1994 by director/producer Tom Shandel, one of Canada’s foremost documentary filmmakers, and interviewer/producer Alan Twigg.

Possibly the most generous and inspiring description of George Woodcock was offered by his oldest friend, Julian Symons, in 1994. “I know of nobody who has been of more generous help to others, or has pursued good ends in life more unswervingly.”

The proceeds from the sale of the Woodcocks’ home on McCleery Street in Vancouver went toward establishing a $2 million endowment that provides aid to working writers struggling to complete projects during times of unforeseen financial hardship. The Woodcock Fund was established in 1989. The Writers’ Trust of Canada, formerly known as the Writers Development Trust, received $1 million from the Woodcock estate in 2005, followed by $876,000 in 2006, and a final installment of $683 in 2009. These bequests, overseen by estate executor Sarah McAlpine, constitute one of the largest private donations to the literary arts in Canada, if not the largest. Between its activation in 2005 and 2009, the Woodcock Fund dispersed approximately $100,000 per year, providing a total of $642,000 to 147 writers who applied. To be eligible, the writer must be working on a book that, without the grant, would be imperiled or abandoned, and the writer must have already published a minimum of two works, as well as face a financial crisis that exceeds the ongoing, chronic problem of making a living. The fund chiefly serves writers of fiction, poetry, plays and creative non-fiction.

In 2007, British Columbia’s lifetime achievement award for an outstanding literary career in British Columbia was renamed the George Woodcock Lifetime Achievement Award. Each year a new recipient of the George Woodcock Lifetime Achievement Award receives a cash prize and a marble plaque honouring the winner is added to the Writers’ Walk — or Woodcock Walk — outside the main entrance of the Vancouver Public Library on Georgia Street. Visit www.georgewoodcock.com for details.

SELECTED PUBLICATIONS: Compiled by UBC Special Collections

Biographies

Amor de Cosmos: Journalist and Reformer

Toronto: Oxford University Press (Canadian Branch), 1975.

Canadian Lives series.

Gabriel Dumont: The Métis Chief and his Lost World

Hurtig, 1975. Reissued by Broadview Press, 2004. Edited by J.R. Miller.

The Anarchist Prince: A Biographical Study of Peter Kropotkin

By George Woodcock and Ivan Avakumovic.

New York: Schocken Books, 1971.

First published in 1950.

Aphra Behn: The English Sappho

Montreal: Black Rose Books, 1989.

Previously published under the title The Incomparable Aphra. London: T.V. Boardman, 1948.

Pierre-Joseph Proudhon: A Biography

Montreal: Black Rose Books, 1987.

William Godwin: A Biographical Study

Montreal: Black Rose Books, 1989.

Criticism

The Crystal Spirit: A Study of George Orwell

Boston: Little, Brown, 1966.

Dawn and the Darkest Hour: A Study of Aldous Huxley

New York: Viking Press, 1972.

The Meeting of Time and Space: Regionalism in Canadian Literature

Edmonton: NeWest Institute for Western Canadian Studies, 1981.

Northern Spring: The Flowering of Canadian Literature in English

Vancouver: Douglas & McIntyre, 1987.

The World of Canadian Writing: Critiques and Recollections

Vancouver: Douglas & McIntyre, 1980.

Canada

Canada and the Canadians

With photos by Ingeborg Woodcock.

Toronto: Macmillan of Canada, 1973.

2nd edition, revised and updated.

Peoples of the Coast: The Indians of the Pacific Northest

Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1977.

The Hudson’s Bay Company

New York: Crowell-Collier Press, 1970.

100 Great Canadians

Edmonton: Hurtig Publishers, 1980.

A Social History of Canada

Markham, Ont.: Penguin Books, 1989.

British Columbia: A History of the Province

Vancouver: Douglas & McIntyre, 1990.

History

George Woodcock

The Doukhobors

By George Woodcock and Ivan Avakumovic.

London: Faber & Faber, 1968.

Into Tibet: The Early British Explorers.

New York: Barnes & Noble, 1971.

Who Killed the British Empire?: An Inquest

London: Cape, 1974.

The University of British Columbia: A Souvenir

George Woodcock and Tim Fitzharris.

Don Mills, Ont.: Oxford University Press, 1986.

Marvellous Century: Archaic Man and the Awakening of Reason (Black Rose, 2008).

Travel

Ravens and Prophets

Victoria, B.C.: Sono Nis Press, 1993.

First published in London: A. Wingate, 1952.

Faces of India: A Travel Narrative

London: Faber and Faber, 1964.

Victoria (photo essay)

Victoria: Morriss Printing, 1971.

With Ingeborg Woodcock

South Sea Journey

Toronto: Fitzhenry & Whiteside, 1976.

Caves in the Desert: Travels in China

Vancouver: Douglas & McIntyre, 1988.

Anarchism

George Woodcock

Anarchism: A History of Libertarian Ideas and Movements

Cleveland: Meridian Books, 1962.

Anarchism and Anarchists: Essays

Kingston, Ont. : Quarry Press, 1992.

Anarchy or Chaos

Willimantic, CT : Lysander Spooner, 1992.

First published London: Freedom Press, 1944.

Essays

Powers of Observation

Kingston, Ont.: Quarry Press, 1989.

Rejection of Politics and Other Essays on Canada, Canadians, Anarchism and the World

Toronto: New Press, 1972.

Periodicals

Canadian Literature

Vancouver: University of British Columbia.

Quarterly.

Edited by George Woodcock from 1959-1977.

London: Freedom Press, 1943.

1st series: 1940-1941.

2nd series: 1943-1947.

George Woodcock: Collected Editorials from Canadian Literature (2012), introduction by Alan Twigg, edited by Glenn Deer and Matthew Gruman. http://canlit.ca/woodcock/ebook

Poetry & Plays

Anima, or, Swann Grown Old: A Cycle of Poems

Coatsworth, Ont.: Black Moss Press, 1977.

The Cherry Tree on Cherry Street: And Other Poems

Kingston, Ont.: Quarry Press, 1994.

Tolstoy at Yasnaya Polyana & Other Poems

Kingston, Ont.: Quarry Press, 1991.

Two Plays

Vancouver: Talonbooks, 1977.

The Island of Demons.

Six Dry Cakes for the Hunted.

Correspondence

The Purdy-Woodcock Letters: Selected Correspondence, 1964-1954

Edited by George Galt.

Al Purdy and George Woodcock.

Toronto: ECW Press, 1988.

Taking It To The Letter

Dunvegan, Ont.: Quadrant Editions, 1981.

About George Woodcock

The Gentle Anarchist: A Life of George Woodcock

Douglas Fetherling.

Vancouver: Douglas & McIntyre, 1998.

George Woodcock

By Peter Hughes.

Toronto: McClelland and Stewart, 1974.

New Canadian library: Canadian writers series no. 13.

A Political Art: Essays and Images in Honour of George Woodcock

Edited by William H. New.

Vancouver: University of British Columbia Press, 1978.

Review of the author’s work by BC Studies:

Beyond the Blue Mountains: An Autobiography

British Columbia: A History of the Province

British Columbia: A Celebration

Canada and the Canadians

The Doukhoborsa

A Picture History of British Columbia

Ashes scattered of remarkable Canadian couple George and Inge Woodcock

Press Release Aug. 13, 2004

Woodcock Charitable Tradition Continues

The mingled ashes of two remarkable Canadian figures in philanthropy and the arts and letters, George and Inge Woodcock, were scattered today in a private ceremony held on Anarchist Mountain near Osoyoos, B.C. George Woodcock died in 1995, and Ingeborg Woodcock in December 2003.

A small group of their closest friends honoured the memory of this remarkable couple—one English, one Austrian— who moved to Canada to live out their shared philosophy of moral anarchism, based on voluntary cooperation of free individuals toward a common good.

Author of more than 100 books and monographs, George Woodcock was a central literary figure on the Canadian literary scene. Inge Woodcock was an intensely private individual who forbade her husband to mention her in his autobiographical writings, and worked behind the scenes as a notably effective fundraiser for such causes as the Tibetan Refugee Aid Society (TRAS, www.tras.ca) and Canada India Village Aid (CIVA, www.civaid.org). Both societies were founded by the Woodcocks, and are still active in Vancouver.

The Woodcocks left the bulk of their estate to the Writers’ Trust of Canada, in a special fund for established Canadian writers in need, and their private art collection to Canada India Village Aid.

CIVA will hold a gala fundraiser, “Acts of Village Kindness,” on Sunday September 12th in the Chan Centre for the Performing Arts, on the campus of the University of British Columbia where George Woodcock taught for many years. Canadian writers, editors, photographers, musicians, and clowns will honour the Woodcock tradition—raising money to assist the poor of rural India through the generosity of the Canadian arts community. Details may be found at www.civaid.org/gala.htm.

A MAN OF FREE INTELLIGENCE: Interview

Q: You and your wife Ingeborg co-founded the Tibetan Refugee Society in the early Sixties after meeting the Dali Lama in Dharamsala. Then you had a private audience with the Dali Lama when he came to Vancouver. Can you tell me about your relationship with him?

WOODCOCK: I find it very hard to analyze. We’re very warm and close to each other. He regards [us] in a very friendly way because we were one of the first people that sought him out and saw what his problems were and started to work on them. He fled in 1959 and we went in ‘61. We had a long talk in Dharamsala and we promised to come back and do something. And we did it. I heard a lot of people promised to do things and never did, but we did. And I think he’s treasured that.

Q: So what you did was to establish a relief agency, which sent money directly to the people who needed it?

WOODCOCK: Yes. A non-governmental agency. We are only patrons in that now. We’ve withdrawn and we are involved in another society we founded that deals with people in India, mainly tribes people, people whose ways of lives are being destroyed by modern development, by deforestation, by this kind of thing. And so it’s a different group of people [Canada India Village Aid Society]. We deal directly, agency to agency. We have managed to create a small working anarchist affiliation group. No vote is ever taken. We arrive at every decision by consensus argued through and it’s become an extraordinary kind of thing.

Q: The Red Cross is definitely not involved. You have purposefully tried to set up an anarchist framework?

WOODCOCK: Yes, an anarchist framework it is essentially.

Q: So anarchism can be a practical model.

WOODCOCK: Yes, it’s an example. Here we do move on consensus. We don’t move on ordinary democratic majority decisions. We don’t have any of that.

Q: Your partner in all of these remarkable undertakings is your wife, Ingeborg, who I know likes to shy away from the public limelight as far as possible…

WOODCOCK: Indeed she does.

Q: So forgive me, Ingeborg, but I’d like you to speak very briefly how she has been important as a partner in your career and in your undertakings.

WOODCOCK: Well, she’s been a wonderful partner for me in my career. She cares for me in sickness and all that kind of thing. She gives me ideas which I sometimes badly need and. on the other hand, with the organizations, she is a superb organizer. I am the ideologue of the group and she is the organizer. Not so much lately, but in the beginning she was.

Q: And you met one another in England in the 1940s?

WOODCOCK: Yes.

Q: When I read through your two volumes of autobiography thus far and I read through your books of poetry it strikes me that there is a great deal more revealed in your emotions in your poetry, would you say that is true?

WOODCOCK: Yes, I would. But then you see people only read what they want to read. Because I am not primarily recognized as a poet, they don’t read my poems. They read my other stuff. They’d learn a lot more stuff if they read my poems.

Q: Well, along those lines I conclude that one of the most influential people in your life as an artist was the anarchist Marie Louise Berneri. You were also a friend of her husband, who was a publisher. Could you tell me a little bit about who she was?

WOODCOCK: Mary Louise Berneri was the daughter of a very famous Italian anarchist, a professor who had to flee from Italy for his beliefs and who was slaughtered by the communists in Spain. She was an admirable person, very beautiful and intellectually extraordinarily bright. In a sense she was the chief personal influence bringing me towards anarchism.

Q: During the war, her husband was charged with sedition.

WOODCOCK: She was, too.

Q: But there was some English law that says a husband and wife can not be tried for the same crime…is that correct?

WOODCOCK: Yes, and so she was let off, which annoyed her thoroughly. Nevertheless she and I carried on the whole operation of the anarchist press until the others came out.

Q: Right, and for a time you had to go underground in England, but that was not the type of underground that people usually associate with the term. You were relatively free to function. Is that correct?

WOODCOCK: Yes, that’s correct.

Q: Surely that experience would influence your life-long anarchism, being essentially an outlaw.

WOODCOCK: Yes, actually it did. Of course I do have the outsider mentality. That’s why I welcome the development these days of the underground economy and that sort of thing. This is the kind of world I like.

Q: What does it mean when you refer to yourself as an anarchist in the 1990s?

WOODCOCK: It means, I suppose, a person for whom freedom is the most important thing—intellectual freedom and, as far as possible, physical freedom. You can be bound by physical things, as I am by certain sicknesses, but nevertheless you can within yourself still be free to recognize all initiatives really come from yourself if you don’t depend upon structures of government or structures of any kind. Structures are fine as long as they are controlled by the people who actually work within the structures, but they’re dicey even there.

Q: But how does that philosophy affect your life on a day-to day-level? in terms of the decisions you make and your behavior?

WOODCOCK: It doesn’t really mean a great deal of difference to a life. You live as you wish to do and if a job is oppressing, you leave it. I’ve done it on several occasions. I broke with the university. It’s a derogatory thing to say it’s a form of evasion, but you evade those unpleasant choices, you evade those situations in which you are insubordinate, you evade the situations that will offend your dignity.

Q: Can you count some specific examples as to how you would respond to something differently than many other people might? Besides rejecting the Order of Canada?

WOODCOCK: My split with the university was over the fact that I had become involved with helping Tibetans in India. I went on a year’s leave to India and did quite a lot. I let a year pass and then I asked for a year’s unpaid leave. For some reason the new president had decided that unpaid leave could only be granted through the decision of a council that consisted almost entirely of scientists and of course they couldn’t understand my reasons for wanting to go so. They said no, no unpaid. So I immediately resigned. When you act dramatically in that way it often has a consequence that is very negative. I was editing Canadian Literature. I didn’t want to let Canadian Literature go so they reached a nice compromise by which I received half a professor’s salary. I was allowed to wander where I could. Here is a case in which you search for your independence and allow something creative to come out of that.

Q: Your affinity with the Doukhobors has a long background. They may not see themselves strictly as anarchists, but there must be some affinity between your beliefs and theirs.

WOODCOCK: Yes, my relationship with the Doukhobors is a very friendly one. Of course when I first started to work on the Doukhobors they were suspicious as they are of all outsiders because they have had a bad press, and that sort of thing, but once I got to know them I found that they were great friends. We had lived among them for short periods with great friendship, great understanding. It’s very hard to place them politically because their leaders are quite prominent but the whole theory behind the Doukhobor movement is that the leaders are the inspired spokesmen of the community and everything is decided at a meeting which is partly a hymn singing religious meeting and partly a meeting to decide the practical affairs of the community. And so they do have this kind of basic anarchy and when the leader makes an announcement it’s always said he is expressing the will of the meeting so they live in a curious kind of half world between anarchism and theocracy. I found it quite fascinating of course.

Q: After you wrote your book The Doukhobors with Ivan Avakumovic, I understand they offered a house to you.

WOODCOCK: They offered to build a house for me in Grand Forks where I could live for the rest of my life for nothing. They call me the Canadian Tolstoy. I didn’t want to Tolstoy living among his admirers. I would probably have no privacy at all. So I decided against it.

Q: In the same way that you had to break with the University of British Columbia because they felt they owned you, the Doukhobors might feel they owned you as well.

WOODCOCK: Right. Yes.

Q: You don’t fully accept the role of national government and yet you are willing to become the first writer to be accorded Freedom of the City. What is the difference between your attitudes to civic government and your attitudes to national government?

WOODCOCK: Well, I think there are all kinds of traditions involved here; first of all the Order of Canada is really a replica of something. We don’t allow people to be knights, to be knighted by the Queen of England, but we do allow them to become members of the Order of Canada. It even has the same phraseology as the English orders of knighthood, companions and this sort of thing. What I’m going to be given I gather is not the key to the city, which in many cities is the case. It’s the freedom medal, and for me freedom has always been associated traditionally with the city. If you think of the Greek city-states where they developed all the ideas of democracy, if you think of the medieval cities where the serf could flee from his lord’s estate, once he got through the gates he was a free man. This is an important tradition, the link between the idea of the city and the idea of freedom. That’s why I’ve accepted it.

Q: It’s also in synch with your whole career as a freelancer.

WOODCOCK: Yes.

Q: You have sold your pen to many places but never to one place for very long.

WOODCOCK: Quite. And never to a political party.

Q: You have always been willing to write for a wide spectrum of publications. I don’t know of any writer who has been in some ways so indiscriminate, in terms of your openness to write for prestigious publications or very small publications. Is that something conscious on your part?

WOODCOCK: It is really. I don’t believe in kicking away ladders. By that, I mean the ladders by which I ascended as a young writer. Small magazines which didn’t pay anything, and that sort of thing. Now I am a writer who can command fairly good payment from magazines with large circulations, I very often refuse to write for them and still write sometimes for the little magazines for nothing.

Q: People around the world think you are remarkable for having written 120 or 150 or God knows how many books. Let’s briefly deal with that. This is a question that pops into many people’s minds. What accounts for that remarkable output? Are you programmed to keep the wolf from the door after so many years of being a freelancer? Are you simply a very hard worker? Or have you succeeded in cloning yourself in your basement?

WOODCOCK: I suppose a very hard worker. That’s really it. I think any writer could do the same as I did, except that if everyone did it would be too much competition.

Q: What strikes me as more remarkable is that you’ve been able to sustain an outsider perspective for so many decades. You have not been taken in by the mainstream. That is actually more remarkable than writing 120 books. What accounts for that endurance and that stubbornness to remain outside for so long?

WOODCOCK: Partly I suppose my Welsh ancestry, partly the fact that I am a Taurian. All sorts of things come together.

Q: I don’t think the astrological Taurian one is an acceptable answer, you are going to have to dig deeper.

WOODCOCK: I think one of the basic things in my life is the death of my father who died young. He was a man of enormous talent, particularly musical talents, but he never had the chance to develop them. I think that after he died I was impelled by the idea of completing that life in my life.

Q: Does it matter to you that your father named you after George Meredith?

WOODCOCK: Well, that shows the kind of atmosphere in the family, the way the family influences on me were going.

Q: You’ve written that creativity often comes out of early wounds, what were your early wounds? beyond the death of your father?

WOODCOCK: My early wounds were the English school system among other things. It wasn’t merely the discipline, it was the ways in which the boys got what was called the school spirit. In most English schools it is a brutal kind of pro-sporty spirit that militates against the intellectual who is looked on as a weakling. I was unpopular at school just because I was an intellectual. I always answered all the questions off the top of my head but they nevertheless resented me because of that.

Q: You’ve also written that school has given you the negative gift of time. What did you mean by that?

WOODCOCK: The negative gift of time, did I say that?

Q: Yup.

WOODCOCK: I suppose it gave me time to hesitate and time to decide who I

was.

Q: Your relations with your father were obviously respectful but your relationship with your mother was more fractious. What type of woman was she?

WOODCOCK: She was a woman, when I look back, of great high principles and that was her trouble. She carried those into all kinds of literal interpretations, so that you are forced to be a liar by her and her demands.

Q: Well it sounds like you must have [nonetheless] inherited, somewhat, her principled nature.

WOODCOCK: Yes, I’d agree, I agree.

Q: And do you feel that you have a paid a price, perhaps even on an emotional level, for having these philosophical standards and these principles?

WOODCOCK: I don’t know whether you’d call it a price. I would say at the end of my life that I’ve probably paid a price but that I’ve been paid back.

Q: In ‘The Outlaw Exonerated’, your poem about Simon Gunanoot, the Gitskan native outlaw, you write ‘and wisdom is sadness before it is joy’. That sounds to me what you just referred to. In order to write ‘and wisdom is sadness before it is joy’ one can only, I think, write that line from deep personal experience.

WOODCOCK: I do, yes.

Q: So you are at the joy stage now.

WOODCOCK: I am at the joy stage now, but…

Q: How long did the sadness stage last?

WOODCOCK: I don’t know. That’s in the command of others, shall we say.

Q: Most of your contemporaries flowered early. Many of them are largely forgotten whereas you have a different type of creativity which seems to be growing in power, literally decade by decade. Do you recognize that your creativity is actually quite abnormal?

WOODCOCK: I suppose I’m lead to do so by the fact of what happened to my contemporaries—people whom I’ve admired people, who I thought were ten times better than me when I was in my Twenties and early Thirties. I may have been right. They may have been that much better but gradually the tortoise, or the bull if you’re going to use the Taurean symbol, marches forward slowly. I think what I am writing now is better than what they were writing when I admired them.

Q: There aren’t many people such as yourself who write increasingly as they get older.

WOODCOCK: Very few.

Q: Most people produce one or two good works, usually maybe in the middle of their life. We’re into the 1990s and you are still steadily producing often three or four books a year.

WOODCOCK: Some are reprints…

Q: Some are reprints, this is true. But it’s still unusual way to approach the end of one’s writing career, to be more prolific than ever.

WOODCOCK: Well, it’s a happy way really because one doesn’t experience so much of the boredom and frustration as the person who gradually creates less and less must do. I look at some of the older writers and I think, my God, what must their lives be waiting for the spark.

Q: Obviously George Orwell was and continues to be a major influence. What do you mean when you refer to him as your dear but difficult friend?

WOODCOCK: I thought I called him my dear, dour George in one of my poems. Orwell was the sort of man who was full of grievances. He was very loyal. Once he got to know you, he was extremely loyal. He hated passionately and irrationally. I remember people who were really quite decent people who tagged along a bit with his bandwagon and our world was full of contempt and fury against them. I used to tolerate them because I thought they were benighted souls, and might somehow show the light, but Orwell didn’t. He just hated them with a bitter fury.

Q: And didn’t you first come into contact with him through a disagreement?

WOODCOCK: Absolutely, yes. I got into a disagreement with him over something he’d said in the Partisan Review. I pointed out that after all he was a former police officer in Burma. He himself had been a pacifist one year before and this kind of thing. And so I wrote this down and Orwell wrote a furious reply. Then somehow or other, through an Indian writer named Mulk Raj Anand, he invited me to take part on his Indian program at the BBC. So I did and we were very formal. And then I was getting on a bus up at Hampstead one day. I was at Hampstead getting on top of a double decker bus on the top deck and I saw a familiar crest of hair. It was Orwell. He’d seen me come across the street. He turned and patted the seat beside him so I went up. He said, “Woodcock, Woodcock, we may have differences on paper but that doesn’t mean anything derogatory to our relationship as human beings.” And with that our friendship started. It was the most extraordinary kind of thing. Same thing happened with Stephen Spender.

Q: When you left England for various reasons, you weren’t able to say good-bye to him…

WOODCOCK: He was in a sanitarium by then.

Q: So is George Orwell still with you today as an influence?

WOODCOCK: I think he is. I remember Herbert Read saying to me once… now, of course, he, too, is dead… but Herbert said, “Whenever I reach a decision these days I feel Orwell’s ghost admonishing me over my shoulder.” This was the effect he had on people. You thought about him and even after he was dead you began to judge your actions by his standards. Orwell was very eccentric.

Q: Do you ever have Orwell’s ghost over your shoulder and he tells you something and you tell him to go away?

WOODCOCK: Well, he never peered over my shoulder as he did over Read’s but nevertheless I’ve thought about him.

Q: I’d like to bring up some other people that you’ve had closer relationships with. First of all the Shadbolts, Jack and Doris.

WOODCOCK: Well, the Shadbolts really were very important. We wouldn’t be in Vancouver if it hadn’t been for the Shadbolts. We’d been living on Vancouver Island and getting pretty miserable, on a village on Vancouver Island that I needn’t name [Sooke] and we came over and Jack said to me, “Well, there’s a cabin in the bush outside, behind our house, maybe we can get you into that.” He tried and yes, the owners would let us go in. At that time all Capitol Hill [in Burnaby] was practically forest. There were no houses. And it was wonderful living out there out in the forest, looking out over the harbour. That’s where we started off in Vancouver. Living together up on this hill we became very close friends.

Q: And since then you have had more friends who were painters than writers, is that true?

WOODCOCK: I really do, yes. I don’t have all that many friends who are writers. I know their problems, but I don’t know the problems of painters. I like to move among painters, mathematicians, psychologists, people who can tell me something.

Q: Another fellow came along and helped put some money in your pocket was Earle Birney.

WOODCOCK: Earle Birney, yes. Earle that was an odd sort of relationship, stormy at the time, very stormy. Earle was a very bad-tempered man and a vain man, but nevertheless…

Q: He touched a lot of peoples’ lives.

WOODCOCK: Well, he did and I think more than any other writer [in British Columbia]. Earle was the first writer in Canada that I knew. Earle actually came and visited me on Vancouver Island, when we were living in a trailer while we were building a house in 1949, the summer of 1949, so he was the first Canadian writer that I knew. He found out I was living there so he came over and later on he was partly instrumental in getting me an appointment to UBC. But there’s a side story to that because he had tried before, he had tried in 1953, and they all said, “No, no, he’s got no degree.” Then in ‘54, the University of Washington offered me a post without a degree and so I went to the University of Washington and worked there for a year. Then they offered me a permanent post and I couldn’t take it because of U.S. immigration which decided that I was, according to the details of the law, an anarchist and therefore inadmissible. So we fought that and failed. Then, surprisingly UBC came back and offered me a job. So I came onto to UBC without a degree, on my own conditions.

Q: And Earle Birney got you to UBC where you met Roy Daniels…

WOODCOCK: Yes, it was it was Earle really. Earle and Roy had a very stormy relationship. Sometimes they’d work together, and they did in getting me into the university. One of the conditions, an implicit condition so that it was never written down, was that I would have a magazine to edit. Roy Daniels made sure of that, that I did have Canadian Literature to edit. So it was the two of them, between them that brought me to the place.

Q: And hence the birth of Canadian Literature which you edited for 18 years. You got to know by mail most of the major Canadian writers. We obviously can’t talk about all of them but I’d like to mention a couple who have been important to you, not just as writers but as friends… Margaret Laurence.

WOODCOCK: Margaret Laurence, yes. Our friendship is [was] an odd kind of epistolary kind of friendship. The few years she was in Vancouver we didn’t know each other very well because I was away quite a lot of the time. I was away in Europe and so I really didn’t get to know her much in Vancouver. Then she left for England and we began to write these long letters to each other. These continued and then at the end, of course, when she moved to Lakefield, there would be the late night phone calls, 2 a.m. Lakefield time. She would go on for hours at a time. I was always anxious about the phone bill but she never rang collect. I don’t know what her bills were like.

Q: She’s a remarkably moving person for anyone who had anything to do with her. Do you think we fully understand who she was, has it been publicly recognized who she was?

WOODCOCK: She was an extraordinarily vulnerable person, much more than her publisher guessed and sometimes you’d get that in these conversations. Someone would have died, it didn’t matter, you didn’t even know the person but Margaret would be emoting about it, genuinely moved, moved, moved to the bottom of her heart about this, and she was a person with extraordinary strong feelings which I think may have had something to do with her final withdrawal from writing.

Q: Another person with whom you’ve corresponded extensively and developed a friendship is Al Purdy. Both of you are autodidacts. Self-taught men.

WOODCOCK: Well, a lot of people find it a little strange, we should be close friends, a rowdy poet and a cautious critic, as some people see me, and so that they think this is all that there can be, an incompatibility. But in fact that isn’t true because we have a great deal in common. A poverty-stricken childhood with a domineering mother, a period of scrounging around for any kind of job we could get, no university education but enormous erudition just by reading, reading, reading. Al is one of the most erudite people I know.

Q: Perhaps self-teaching takes you longer to find yourself but when you do get there, you’re stronger for having taught the lessons yourself.

WOODCOCK: I think you are. I think if you look at the great self-taught men of literature, Joseph Conrad for instance… He ran around all the university-educated men of his time.

Q: Hardy?

WOODCOCK: [Thomas] Hardy, yes, Arnold Bennet. A whole lot of them.

Q: Can you tell me what the relationship with Margaret Atwood is and why you continue to be close friends?

WOODCOCK: Well, it’s a relationship of people who really emerged at the same time. When I started to publish Canadian Literature, Peggy was starting to publish her own poetry and novels. I was one of the first people to recognize, what was it called? the first novel?

Q: The Edible Woman.

WOODCOCK: Yes. I was one of the first people to recognize The Edible Woman with a good review in The [Toronto] Star. She’s never quite forgotten that. Also, I used to call on Peggy as a critic. She’s a damn good critic, so she did quite a lot of work for Canadian Literature. This was in the past of course, but we still continue a kind of sporadic relationship, writing to each other every now and again. Everything I ask Peggy to do, such as report on a cause of mine, she regularly does without complaint. So there is a friendship there, an odd one, but a friendship.

Q: You’ve written books about Gabriel Dumont and Simon Gunanoot… Simon Gunanoot was on the run for 12 years. Now the city of Vancouver is officially acknowledging your importance as an outsider. It strikes me this is an interesting stage in your life, as if society is saying we recognize the importance of where you have been all this time. Do you see it that way?

WOODCOCK: To an extent I do, because they’re making the outsider into an insider, aren’t they? Taking him into the city in the most intimate way they can.

Q: So you are accepting this quite consciously.

WOODCOCK: Yes, consciously. Because I believe in that connection between

freedom and the city.

Q: Right. The third and final volume of your autobiography is forthcoming. What’s the title and what are we going to find in it?

WOODCOCK: The title is Walking Through the Valley, meaning walking near to death, the valley of the shadow. It’s a summing up in a sense. It’s an account of the things I’ve done in the last 15 years, but it’s also a reflection on life as a whole. I say a lot about the process of autobiography and what I think writing a biography does to you, and how it does change your perspective. You realize your life in fact, as you conceive it, is a great fiction. Writing an autobiography is in a way elucidating the fiction.

Q: You also have a new book of poetry coming out, The Cherry Tree on Cherry Street. Could explain the title?

WOODCOCK: The title refers to the cherry tree in my garden. Once the street where I live [McCleery Street] was called Cherry Street.

Q: What lies ahead, what are you working on?

WOODCOCK: I’m working on a novel. I wrote three novels in the past and destroyed them because I thought they were no good. That turned me into quite a good literary critic, because I knew what faults to look for. Then I decided to write a novel quite recently which was based on a film script. Like all writers I got involved in a peripheral way in the film industry and found that they do pay quite well for things they never use. I decided to take one these plots and turn it into a novel. I’ve been using all kinds of experimental techniques on it so I don’t know what it’s going to come out [as] in the end.

Q: It seems to be the last type of book that you haven’t published.

WOODCOCK: It is, yes. I’ve published plays. I’ve published everything else.

Q: And you’re also translating some Proust.

WOODCOCK: Yes. A lot of writers like Nabokov complain about the translations. It was translated during the 1920s and it followed the English idiom of translations. It was very sentimental, Elizabethan sentimental. The very title of course, Remembrances of Things Past, has nothing to do with the real title, which is Search for Lost Time. So I decided it was time to do a new one.

LARGEST CASH GIFT TO WRITERS IN CANADIAN HISTORY: Press Release (2006)

WRITERS’ TRUST RECEIVES CLOSE TO $2 MILLION FROM GEORGE AND INGEBORG WOODCOCK ESTATE

Vancouver – May 19, 2006 – The Writers’ Trust of Canada announced today it has received an extraordinary $1.87 million gift from the estate of George and Ingeborg Woodcock. These funds will enable the Writers’ Trust’s Woodcock Fund to provide more than $100,000 annually to Canadian writers facing financial crises. Most of the monies available to Canadian writers are in the form of literary prizes; the Woodcock Fund is unique in that it offers help to struggling and established authors alike.

Ronald Wright, Chair of the Writers’ Trust Woodcock Committee, explained: “The Woodcock Fund is one of the many enduring legacies funded by the Woodcock’s generous, passionate, and unflagging engagement with the world. I was also lucky enough to know Inge and George personally over the past twenty years, ever since I was a young writer with a first book. Many authors received the Woodcocks’ encouragement and friendship, which are rare gifts, and especially so from our heroes.”

The Woodcock fund was established in 1989 through the generosity of George and Ingeborg Woodcock, who sought to alleviate the devastating impact of financial instability endured by most writers. It is the only program of its kind in Canada. Since its inception, the Woodcock Fund has made an extraordinary difference in the lives of Canadian writers, distributing more than $420,000 in financial support to more than 110 writers.

“Writers are one of Canada’s greatest exports,” said Don Oravec, Executive Director of the Writers’ Trust of Canada, “yet many endure near poverty. This increased support of the Woodcock Fund will encourage and preserve our literary heritage by rescuing those works that might otherwise be abandoned.”

Canada’s writers, on average, earn less than $9,000 annually from their writing, according to A Study of Author Income, commissioned by the Department of Canadian Heritage and the Canada Council for the Arts in December 2003.

The Woodcock Fund recipients are guaranteed anonymity; however, some choose to offer their gratitude publicly:

The generous and timely patronage of the Woodcock Fund alleviated a huge emotional burden,” said Pearl Luke, author of the recently published novel Madame Zee. “The emergency grant meant that I moved through a time of hardship and real despair, and it restored a sense of hopefulness about my career. I am forever grateful.”

The Writers’ Trust hopes this announcement will alert Canadian writers to the existence and nature of the help offered through the Woodcock Fund.

A reception celebrating the $1.87 million bequest will be held on Wednesday, May 24 in Vancouver where the Woodcocks lived for most of their lives.

ABOUT GEORGE AND INGEBORG WOODCOCK

Editor, poet, critic, travel writer, historian, philosopher, essayist, biographer, autobiographer, political activist, university lecturer, librettist, humanitarian, gardener…George Woodcock was a literary champion, founder of the journal Canadian Literature in 1959, which provided a much-needed resource for the exploration and celebration of the works of Canadian literary authors.

While rooted in Canada and British Columbia, British-born George and his Austrian-born wife Inge kept a keen eye on political events in the rest of the world. After the Chinese takeover of Tibet, they took up the plight of displaced Tibetans and travelled to India to study Buddhism. There, they established a close friendship with the Dalai Lama who never forgot George and Inge’s lifelong commitment to Tibetans both in Canada and in India through the Tibetan Refugee Aid Society, which they founded. Once the Tibetan refugees were largely settled, George and Inge turned their attention to their passion for India and founded the Canada India Village Aid Society which works to foster self-help schemes in rural Indian communities.

Worldwide, George Woodcock is best known for his books on the philosophy of anarchism and its history, and for his well-received biography of his friend George Orwell, The Crystal Spirit, for which he received the Governor General’s Award in 1966. He taught at the University of British Columbia from 1955 into the 1970s, and was awarded an honourary DLitt by UBC in 1977 (he received five honorary degrees from other universities). He refused many awards, including the prestigious Order of Canada, choosing to accept only those given by his colleagues and peers.

In 1994, Vancouver’s mayor awarded George Woodcock the Freedom of the City and declared May 7 as George Woodcock Day. Although George accepted the honour, ill health prevented him from attending the festivities, which included the largest gathering of authors in Western Canada (Margaret Atwood read out his speech), a gallery showing of new art created in his honour, and a two-day symposium celebrating his lifetime work at Simon Fraser University’s downtown campus. Less than a year later, George Woodcock died at his home, at age 82, on January 28, 1995. Inge survived him until 2003.

The Writers’ Trust of Canada is a national charitable organization providing a level of support to writers unmatched by any other non-governmental organization or foundation. Through its various programs and awards, it celebrates the talents and achievements of our country’s novelists, poets, biographers, and non-fiction writers. The Writers’ Trust is committed to exploring and introducing to future generations the traditions that will enrich our common literary heritage and strengthen Canada’s cultural foundations. For more information, please visit www.writerstrust.com.

Complete Bibliography (1994)

from Anarchy Archives & Woodcock Symposium

The Works of George Woodcock

To accompany an exhibit of his works at the George Woodcock Symposium,

Simon Fraser University at Harbour Centre, May 6 and 7, 1994

This chronological checklist of George Woodcock’s work includes books, pamphlets, broadsides, and periodicals written, edited, or compiled by him. His own work is followed by translations, symposia, anthologies, and books and series George Woodcock has edited with introductions.

This list is based on The Record of George Woodcock (issued for his eightieth birthday) and Ivan Avakumovic’s bibliography in A Political Art: Essays and Images in Honour of George Woodcock, edited by W.H. New, 1978, with additions to bring it up to date.

BOOKS, PAMPHLETS, AND BROADSIDES BY GEORGE WOODCOCK

1. Solstice. London: C. Lahr, 1937. Folded card.

2. Six Poems. London: Blue Moon Press for E. Lahr, 1938. Single sheet of grey stiff paper folded into four.

3. Ballad of an Orphan Hand. London: C. Lahr, 1939. Folded card.

4. The White Island. London: Fortune Press, 1940.

5. The Centre Cannot Hold. London: Routledge, 1943.

6. New Life to the Land. London: Freedom Press, 1942.

7. Railways and Society. London: Freedom Press, 1943.

8. Anarchy or Chaos. London: Freedom Press, 1944. Wilimantic, Connecticut: Ziesing, 1992, with a new introduction by author.

9. Homes or Hovels: The Housing Problem & its Solution. London: Freedom Press, 1944.

10. Anarchism and Morality. London: Freedom Press, 1945.

11. What is Anarchism? London: Freedom Press, 1945.

12. William Godwin: A Biographical Study. London: Porcupine Press, 1948. Norwood, Pennsylvania: Norwood Editions, 1976. Montreal: Black Rose Books, 1989, with a new introduction by the author.

13. The Basis of Communal Living . London: Freedom Press, 1947.

14. Imagine the South. Pasadena: Untide Press, 1947.

14a. A Hundred years of Revolution, 1848 and after. [a collection of essays and documents]. London: Porcupine Press 1948.

15. The Incomparable Aphra. London: T.V. Boardman, 1948. Montreal: Black Rose Books, 1989, as Aphra Behn, The English Sappho, with a new introduction by the author.

16. The Writer and Politics. London: Porcupine Press, 1948. Montreal: Black Rose Books, 1990, as Writers and Politics, with a new introduction by the author.

17. (With Ivan Avakumovic.) The Anarchist Prince: A Biographical Study of Peter Kropotkin. London: T.V. Boardman, 1950. New York: Schocken Books, 1971. Montreal: Black Rose Books, 1990, as From Prince to Rebel, with a new introduction by George Woodcock.

18. The Paradox of Oscar Wilde. London: T.V. Boardman, 1950. New York: Macmillan, 1950. Montreal: Black Rose Books, 1989, as Oscar Wilde: The Double Image, with new introduction by the author.

19. British Poetry Today. Vancouver: University of British Columbia, 1950.

20. Ravens and Prophets: An Account of Journeys in British Columbia, Alberta and Southern Alaska. London: Allan Wingate, 1952.

21. Pierre-Joseph Proudhon, A Biography. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul, 1956. New York: Schocken Books, 1972, as Pierre-Joseph Proudhon, His Life and Works. Montreal: Black Rose Books, 1987, with a new introduction and bibliographical supplement by the author.

22. To the City of the Dead: An Account of Travels in Mexico. London: Faber and Faber, 1957.

23. Incas and Other Men: Travels in the Andes. London: Faber and Faber, 1959.

24. Anarchism: A History of Libertarian Ideas and Movements. Cleveland: World Publishing, 1962. Harmondsworth: Penguin Books, 1963. Harmondsworth: Pelican edition with author’s postscript, 1975. Harmondsworth: Pelican edition with a new introduction and bibliography by the author.

25. Faces of India, A Travel Narrative. London: Faber and Faber, 1964.

26. Asia, Gods and Cities: Aden to Tokyo. London: Faber and Faber, 1966.

27. Civil Disobedience. Toronto: Canadian Broadcasting Corporation, 1966.

28. The Crystal Spirit: A Study of George Orwell. Boston: Little, Brown, 1966. London: Jonathan Cape, 1967. Harmondsworth: Penguin Books, 1970. London: Fourth Estate, 1984, with a new introduction by the author. New York: Schocken Books, 1984, with a new introduction by the author.

29. The Greeks in India. London: Faber and Faber, 1966.

30. Kerala, A Portrait of the Malabar Coast. London: Faber and Faber, 1967.

31. Selected Poems of George Woodcock. Toronto: Clarke, Irwin, 1967.

32. (With Ivan Avakumovic.) The Doukhobors. London: Faber and Faber, 1968. Toronto: Oxford University Press, 1968. Toronto: McClelland & Stewart, 1977, with a new introduction by the authors.

33. The British in the Far East. London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson, 1969. New York: Atheneum, 1969.

34. Henry Walter Bates, Naturalist of the Amazons. London: Faber and Faber, 1969.

35. Hugh MacLennan. Toronto: Copp Clark, 1969.

36. Canada and the Canadians. London: Faber and Faber, 1970. London: Faber and Faber, 1973, revised. Toronto: Oxford University Press, 1970. Toronto: Macmillan of Canada, 1973, revised.

37. The Hudson’s Bay Company. New York: Crowell-Collier Press, 1970.

38. Mordecai Richler. Toronto: McClelland & Stewart, 1971.

39. Odysseus Ever Returning: Essays on Canadian Writers and Writing. Toronto: McClelland & Stewart, 1970.

40. Into Tibet: The Early British Explorers. London: Faber and Faber, 1971.

41. Mohandas Gandhi. New York: Vintage, 1971. London: Fontana/Collins, 1972, as Gandhi.

42. Victoria. Photo-Essay by Ingeborg & George Woodcock. Victoria: Morriss Printing, 1971.

43. Dawn and the Darkest Hour, A Study of Aldous Huxley. London: Faber and Faber, 1972. New York: Viking Press, 1972.

44. Herbert Read: The Stream and the Source. London: Faber and Faber, 1972.

45. The Rejection of Politics and other essays on Canada, Canadians, anarchism and the world. Toronto: new press, 1972.

46. Who Killed the British Empire? An Inquest. London: Jonathan Cape, 1974. New York: Quadrangle, 1974. Toronto: Fitzhenry & Whiteside, 1974.

47. Amor De Cosmos, Journalist and Reformer. Toronto: Oxford University Press, 1975.

48. Gabriel Dumont: The Metis Chief and his Lost World. Edmonton: Hurtig, 1975.

49. Notes on Visitations: Poems 1936-75. Toronto: Anansi, 1975.

50. South Sea Journey. London: Faber and Faber, 1976. Don Mills: Fitzhenry & Whiteside, 1978.

51. Gabriel Dumont and the Northwest Rebellion. Toronto: Playwrights Co-op, 1976.

52. Canadian Poets 1960-1973, A Checklist. Ottawa: Golden Dog Press, 1976.