#95 Oliver Wells

January 28th, 2016

LOCATION: Edenbank Farmhouse, 7001 Eden Drive, Chilliwack

Built in 1913, the Edenbank Farmhouse in which Oliver Wells lived can be found within an adult-oriented housing complex called Edenbank. Oliver Nelson Wells (1907-1970) was a Fraser Valley stock breeder and farmer who began to sense his Chilliwack River neighbours were on the threshhold of losing their culture in the 1950s. His sidelong career as an ethnographer began after he wrote the introduction to the Sepass Poems, edited by Eloise Street, “to let the readers know that [Chief William] Sepass was a reality and a highly respected man.”

ENTRY:

Carrying a tape recorder and sketch pad, Oliver Wells began to document the memories and knowledge of his Aboriginal friends and their leaders. He then began to venture further afield from Chilliwack, initially to interview Chief August Jack Khahtsahlano of the Squamish. “I went mainly because Eloise Street told me that August Jack had the same religious training and background that Sepass had,” he recalled in a 1970 letter. “…I am one of the few White people who get into the ‘power dances’ which our local Indians are reviving. This is the closest I have come to being intimately associated with the Native in a primitive cultural experience. You have to see and hear it to realize it is possible. The wonderful thing about these big dances is that the Indians set a high standard of behavior and etiquette, and do their own policing, very effectively. Three or four hundred Indians, from babes in arms to old people—all in harmony, with maybe thirty drums beating in a small hall, makes an impressive accompaniment for a lone dancer dramatizing his ‘power’. Some of the finest people I know are devout religious men and women of our local tribes who have accepted Christianity but, like Sepass, see no wrong in the good things of the old ways.”

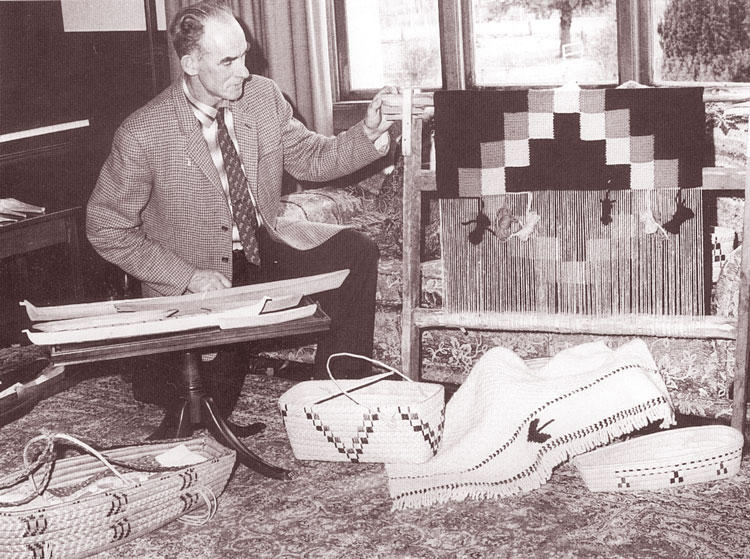

Wells’ invaluable work as an ethnographer was later condensed into The Chilliwacks and Their Neighbours (Talonbooks, 1987), edited by Ralph Maud, Brent Galloway and Marie Weeden. It contains interviews with August Jack Khatsahlano, Domanic Charlie, Chief Albert Louie, storyteller Dan Milo, historian Bob Joe and Wells’ friends such as Mrs. August Jim (to whom Wells dedicated one of his research publications). Wells is credited with helping to preserve the Halkomelem language, reviving Salish weaving techniques, transcribing legends and tracing family trees. His interviews with Domanic Charlie and August Jack Khatsahlano formed the basis for Squamish Legends (Vancouver: C. Chamberlain and F.T. Coan, 1966), of which Wells has been listed as both editor and author. His other works include Salish Weaving Primitive and Modern, As Practiced by the Salish Indians of South West British Columbia (Sardis: 1969) and Myths and Legends of South Western British Columbia: STAW-loh Indians (Sardis: 1970).

Wells’ writings and life are recalled in a family history entitled Edenbank: The History of a Pioneer Canadian Farm (Harbour, 2003), edited by Richard and Marie Weeden. The Edenbank farmhouse was designed by renowned Vancouver architect Thomas Hooper. According to UBC Special Collectons: Edenbank Farm was the home of five succeeding generations of the Wells family. Allen Casey Wells (1837-1922) moved to Chilliwack in 1866 to manage the large land holdings of his brother-in-law, Charles Evans. He later purchased over 450 acres of farmland for his family. Wells’ Edenbank Farm produced hay, root crops, and dairy products. Wells established the first creamery and cheese factory in the Chilliwack area and later established the Edenbank Trading Company, a general store. A.C. Wells served as Reeve of the Township of Chilliwack from 1897 to 1901. Edwin Wells assumed active management of the farm in 1912. Edwin’s son, Oliver Wells, became the proprietor of the farm in 1939. In 1966, it became a family-owned company, Edenbank Farm Ltd. The main farmhouse has been preserved.

Review of the author’s work by BC Studies:

The Chilliwacks and Their Neighbors

Edenbank: The Story of a Canadian Pioneer Farm

BOOKS:

Charlie, Domanic & August Jack Khatsahlano. Squamish Legends (Vancouver: C. Chamberlain and F.T. Coan, 1966). Interviews by Oliver N. Wells.

Wells, Oliver N. Salish Weaving Primitive and Modern, As Practiced by the Salish Indians of South West British Columbia (Sardis: 1969).

Wells, Oliver N. Myths and Legends of South Western British Columbia: STAW-loh Indians (Sardis: 1970).

Wells, Oliver N. The Chilliwacks and Their Neighbours (Talonbooks, 1987). Edited by Ralph Maud, Brent Galloway and Marie Weeden.

Wells, Oliver N. Edenbank: The History of a Pioneer Canadian Farm (Harbour, 2003). Edited by Richard and Marie Weeden.

[BCBW 2015]

Edenbank: The History of a Pioneer Canadian Farm review by Mark Forsythe (2003)

The story of Edenbank Farm begins with a case of gold fever. Twenty-five year old Allen Wells leaves his new bride Sarah Wells in Ontario to strike out for the Cariboo gold fields.

It’s 1862, he travels via New York to the Isthmus of Panama, overland to San Francisco, up the coast by ship to Victoria and then aboard a steamboat to New Westminister. Once there, he hires a Sto:lo paddler named Big Jim to get him to the trail head where he starts his 500-mile walk to Barkerville with supplies on his back.

Like so many, Allen fails to strike it rich. He leaves the gold fields broke. On the return journey through the Fraser Canyon, he settles in Yale where he outfits the first four-horse stage coach to travel the Cariboo Road—B.C.’s first mega-project.

Sarah joins Allen in Yale, and within three years their first child is born. Wells moves south to manage his brother-in-law’s farm near Sardis. Big Jim paddles him upstream to a native trail where Wells stakes his own claim to 320 acres on the Luckakuck River. The back-breaking work begins: carving a farm from the wilderness and swamp by hand and oxen.

Help comes from local Sto:lo axmen. And so begins a friendship that lasts for generations. The land produces excellent potatoes, beans and carrots. The lush and fertile loam at the base of Cheam Mountain Range inspires the family to christens the farm Edenbank.

Allen Wells’ grandson Oliver Wells puts the gold rush gamble into perspective in Edenbank: The History of a Pioneer Canadian Farm (Harbour $36.95), edited by Richard and Marie Weeden, when he writes “The true wealth of the country was in the gold of the earth – the products of the soil.”

Much of Edenbank is being published more than 35 years after Oliver finished writing it. His daughter Marie Weeden remembers her father “sitting in front of a warm fire lit in the dining-room grate, perhaps with a woollen sweater draped over his shoulders, reading old records and diaries and, with pen in hand, composing the farm’s story.”

Oliver Wells completed the story in 1967, and died after an accident three years later. Marie and her husband kept the project alive with encouragement from family, friends and local historians.

Edenbank chronicles 100 years of farm life in sometimes minute detail: stumps are pulled, bulls purchased, barns built, and beds crafted from rough lumber. Strong ties are forged with neighbours, and a powerful sense of community is evident throughout.

In 1896 Wells helped develop the first farmer’s co-operative in Western Canada in order to produce butter and cheese for a growing Lower Mainland. He tells his son Edwin, “once we get the farm cleared, drained and fenced, we will then be in a position to make some money!” Edenbank became one of B.C’s largest and most successful dairy operations, admired nationally for its blue ribbon Ayrshire cattle.

Allen was also an innovator, experimenting with new crops and introducing new dairy farming methods (a creamery and upright silos) later adopted by others. No drinkers or smokers need apply as hired hands, Wells wanted “a respectable, gentlemanly, clean lot of men.” Among his crew were Sto:lo and Chinese who had worked on the CPR right-of-way.

In 1867 Allen and Sarah saw firsthand the ravages of smallpox. Reverend Thomas Crosby came into the valley with a vaccine and took Wells with him to a local native village. “The chanting of the medicine men and the wailing of lamenting mothers could be heard long before they rounded the bend in the river…they were horrified to see the natives throwing their children into the cold river waters. To the natives, the fever in the children was the result of evil spirits having entered their bodies. They were desperately trying to drive them out by casting the children into the water.”

Oliver Wells was born in 1907, the same year a telephone line was strung into the Fraser Valley. “Oliver, the new baby born to Gertie Wells on May 21, was able to cry loudly enough in New Westminster to be heard sixty miles away by his father in Chilliwack.”

In his Edenbank manuscript, Oliver Wells recalls watching the first train roll down the newly constructed BC Electric Railway which also marked electricity’s arrival on the farm. “Only three years of age I can remember being hoisted onto my father’s shoulders for the rush to the lane gate to watch the big train come in…”

There are assorted photos of farm life: teams of oxen, dairy herds and a splendid image of Oliver and his wife Sarah on a ride to the top of Liumchen Mountain. Oliver stands in front of two horses holding their reins while Sarah stands perched on their backs like a circus rider. Both are wearing huge grins and the perspective from the mountaintop makes it seem like they’re floating above the valley.

After the tough Depression years Oliver took over in 1939 as the third generation to farm Edenbank; he continued to breed prize-winning dairy cattle, and later Aberdeen Angus beef cattle and Cheviot sheep. A budding naturalist, he created a sanctuary by bringing back ponds and marshlands. Birds returned in great numbers.

In the 1950s Oliver Wells bought a reel-to-reel tape recorder to interview Sto:lo elders about their culture, language and traditions. These recordings are still highly valued by the Sto:lo and are credited with helping preserve the Halkomelem language. Oliver also helped the Sto:lo revive their Salish weaving tradition, and to breed sheep to produce black wool for finely woven sweaters and tapestries. Along the way he was the first president of the Chilliwack Historical Society.

Today Edenbank is gone—sold and subdivided. The elegant farm house still stands behind the gates of what’s now an upscale housing complex. This is a sore point for daughter Marie and other heritage advocates who lament the fact a plan to preserve the farm on a proposed college campus was given a thumbs down by the Agricultural Land Reserve Commission. Later attempts to secure provincial and municipal heritage status failed, although the wildlife sanctuary is now operated by the Wells Sanctuary Society. The pages of Edenbank will do much to keep the legacy of this remarkable pioneer farming family alive.

Journalist Allan Fotheringham was eight years old when his family moved into the hired man’s house at Edenbank. He salutes Oliver in the Foreword. “His death in Scotland, on his first and only trip abroad, was of course a major loss not only to his family, to Edenbank, to Sardis and to B.C. but to Canada as a whole. Because he set an example of how fine a man could be.”

1-55017-303-0

A.C. Wells Clubhouse

An article by Jenna Hauck – Chilliwack Progress, Aug 6, 2013

A 100-year-old piece of Chilliwack history will be home again to one of its original residents.

Sixty years after moving out of her family home on a dairy farm in the mid ’50s, Marie Weeden is returning with her husband, Dick.

The history of the farm site itself goes back even further. The original 450-acre plot of land owned by the Wells family has gone through a lot of changes over its 146 years.

In 1867, Allen Wells, the great-grandfather of Weeden, purchased the vast property and built a dairy farm on it, known as Edenbank Farm. It was located in Sardis, on the west side of Vedder Road near Spruce Drive.

In 1913, Weeden’s grandfather, Edwin Wells, tore down the original farmhouse and built the current Edenbank house with wife Gertrude, all while raising a young family. Weeden’s father, Oliver, was just six years old at the time and he grew up on the farm with his four brothers.

“Oliver wanted to be a farmer so he continued on the farm,” says Weeden.

In 1931, Oliver got married to Sara McKeil. They had a small family of two daughters — Marie (1935) and older sister Betty (1933).

When Weeden was a child, she and her friends used to roller skate in the attic.

She moved out in the ’50s and eventually became the owner of the family home.

When she moved back in the ’70s, she papered the walls with old newspapers that her family had kept about the history of the Fraser Valley.

Over the years, it was mostly members of the Wells’ family who lived there until the ’70s.

In 1981, the property was sold to Chilliwack’s Brodel Development Corp., owned by Eldon Unger, who turned 12 acres of the land, surrounding the house, into a multi-housing subdivision for adults aged 55 and older. The 1913 farmhouse now stands tall in the middle of the adult-oriented complex, appropriately known as Edenbank.

The house has since been transformed from a residential building into the complex’s clubhouse all while maintaining the house’s original features.

Though 100 years old, the historic heritage house remains in beautiful condition with its warm hardwood flooring, colourful stained-glass windows, broad entryways into the living and dining rooms, brass-and-tile fireplace, and its lovingly hand-crafted nameplates which still hang above the boys’ bedroom doors upstairs, from when Oliver was a child.

The house is used on a daily basis and is officially known as the A.C. Wells Clubhouse. The residents of Edenbank hold meetings there, and it’s used regularly for reading in the library, playing cards in the games room, and having a drink with neighbours at the bar.

On July 20, current and past residents of Edenbank gathered to celebrate the house’s centennial anniversary. Tables were set up with photos, newspaper articles, and more on the history of Edenbank Farm.

Edenbank has just about everything one can ask for in a multi-housing complex.

Attached to the back of the clubhouse is a pool, hot tub, sauna, weight room, tennis court and squash court. A one-kilometre long pathway meanders through the entire subdivision and around the detached homes, townhouses, duplexes, and condos which surround the clubhouse. A large, grass field runs along the west side of the property where resident practice their golf swings. A creek hugs the houses on the east side, and behind it is a thick wall of trees which blocks nearly all the traffic sounds from Vedder Road, located only metres away.

“It’s quite a little gem right in the middle of town,” says 15-year-resident Jan VanderHoek.

This month, Marie and Dick Weeden are moving into one of the condos at Edenbank, a place she can once again, call home.

To find out more about Edenbank, you can read the book Edenbank: The History of a Pioneer Farm. You can borrow it from the Chilliwack Library, or it’s available for purchase at the Chilliwack Museum.

Leave a Reply