#578 Roughing it at the Cove

July 13th, 2019

Boom & Bust: The Resilient Women of Historic Telegraph Cove

by Jennifer Butler

Victoria: Touchwood, 2019

$26.00 / 9781771512985

Reviewed by Heather Graham

*

In 1911 or so, Alfred Marmaduke Wastell, known to all as Duke, informed his wife, Mame, that he had “bought out a bad loan on some land across the Johnstone Strait.” Despite the fact that he wasn’t very good at it, Duke liked to dabble in financial matters, much to Mame’s dismay (she would call him a jackass more than once over the years), and as far as she was concerned, this purchase of 376 acres of bush in an isolated cove five miles away from their home on Cormorant Island was just his latest bad investment. She was not impressed.

In 1911 or so, Alfred Marmaduke Wastell, known to all as Duke, informed his wife, Mame, that he had “bought out a bad loan on some land across the Johnstone Strait.” Despite the fact that he wasn’t very good at it, Duke liked to dabble in financial matters, much to Mame’s dismay (she would call him a jackass more than once over the years), and as far as she was concerned, this purchase of 376 acres of bush in an isolated cove five miles away from their home on Cormorant Island was just his latest bad investment. She was not impressed.

Such was the inauspicious beginning of Telegraph Cove.

Duke worked for B.C. Fishing and Packing Co. In Alert Bay, managing the mill that made the wooden boxes used for shipping the company’s salmon. From Duke’s point of view, his latest purchase made perfect sense. The land had already been surveyed for logging, so he also bought the timber lease from the previous owner and started hauling logs to the mill in Alert Bay. The telegraph part of the story made its appearance in 1912, when the federal government came in search of a site for a telephone-telegraph line from Campbell River to northern Vancouver Island. Duke thought his little cove was just the place. A name was required so that the station could be located on a map, and Duke proposed the obvious: Telegraph Cove. Within a few years the line would be moved to Alert Bay, but the name would not change. Telegraph Cove it would remain.

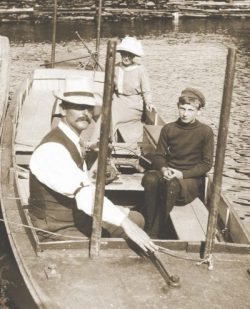

Duke Wastell, Mame (Mary Elizabeth Wastell, née Sharpe), and Fred Wastell at Telegraph Cove, circa 1914

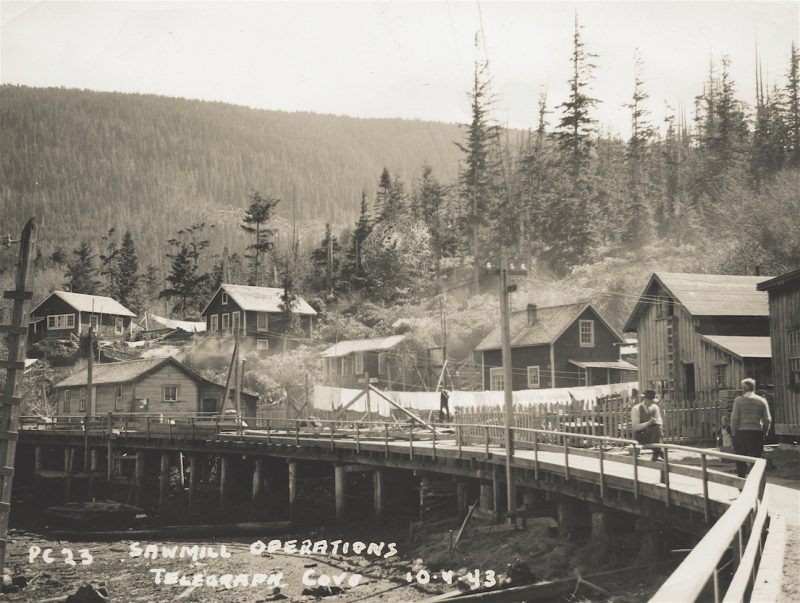

In the mid 1920s, Duke built a basic sawmill at the Cove and went into business with some Japanese partners in a salmon saltery. Apart from the workers needed for these two economic activities, there was no community as such, a situation that would change before the decade was over. First, B.C. Fishing and Packing Co. switched to corrugated cardboard for its boxes, putting Duke out of a job. It also put Duke’s son Fred, the factory’s bookkeeper, out of a job. Second, the Great Depression began, changing life even in remote corners of the world such as the North Island.

Although they had to give up the house provided by Duke’s former employer, Duke and Mame were not homeless; over the years Mame, who had her own money, had bought a number of houses in Alert Bay, so the older generation of Wastells decided to stay put. The younger Wastell had other ideas. Now unemployed and also newly married, Fred packed up his wife, Emma, and relocated to Telegraph Cove, where they set up housekeeping in the house originally occupied by the linesman who had once looked after the long departed telegraph station. For the little Cove, the future had just arrived.

Boom & Bust: The Resilient Women of Historic Telegraph Cove, Jennifer L. Butler’s engaging new book, is not the first to tell the story of this coastal community, although it is the first to gather together its female residents and position them in the foreground of the canvas. In 1995, Harbour Publishing put out Time & Tide: The History of Telegraph Cove (Raincoast Chronicles no. 16), written by Pat Wastell Norris, who just happens to be Jennifer Butler’s aunt. Not surprisingly, then, both books include a great deal about the Wastells, the Cove’s founding family, but Butler’s book is much more expansive, sometimes in spite of the author’s intention to focus on the experiences of its women.

But let’s begin at the beginning, with the title.

The term “boom and bust” describes a period of economic prosperity followed by economic decline. It conjures up images of workers pouring into the site of mine or a mill, near a town that exists only to service those labourers, with its saloons and other boomtown “amenities.” When the mine is depleted, or the market changes, the capitalist money moves on, as do the workers; at least, those who can will move on, while those who can’t remain stuck in a place with no reason to exist.

Given the meaning of the term, Boom & Bust is an odd choice for the title of Butler’s book. In its lifetime as a vibrant community — ninety years and counting — Telegraph Cove has experienced none of the trauma associated with economic extremes; its early history is more a story of ups and downs, with really only one down, the Great Depression, and that only at the very beginning. Times were tough, yes, but life went on. In fact, the little community grew; the mill continued to produce, and there was always someone looking for work. Families began to arrive, bringing children who needed an education, as did Fred and Emma’s two daughters, Pat and Bea. Soon there was a school. With the start of the Second World War, workers decamped for military service, but the RCAF came in to take their place because that mill needed to keep producing. In the post-war years, prosperity was never absent from the Cove, right up to the present day.

Fred’s sawmill closed in the early 1980s, but by then there was a new kind of economic activity at the Cover, and a new generation of residents. Nature as tourism, rather than as a source of market commodities, had made its appearance in the world.

The subtitle of Butler’s book, The Resilient Women of Historic Telegraph Cove, makes it clear right up front what angle she wants to take on her story. The book is divided into four sections, two of them chronological — pioneer women, postwar women — two of them thematic — professional women, whale-watching women — although the section on whale-watching women is inextricably linked to a particular time and is therefore just as much chronological as thematic. The pioneer women were Mame Wastell, her daughter-in-law Emma, and four Japanese women married to men involved in the Telegraph Cove economy. The professional women were the schoolteachers who passed through the community over the years, plus a couple of bookkeepers, a postmistress, and a general store shopkeeper. The postwar grouping is made up mostly of the wives of men employed by the mill, but there are a few exceptions. As for the final category, it includes three women married to men in the whale-watching business; two of the women were married to the same man, although not, it must be said, at the same time.

There’s no question that the women portrayed in Butler’s book were hard working, and also of course resilient, perhaps by necessity. Given the various obstacles they had to deal with in their everyday lives, never mind emergencies and the unexpected, their sheer tenacity is remarkable. There is, however, an unevenness to the book; some of the women are given much more prominence than others — Emma Wastell’s life, for example, is presented in great detail — while others have such a minor connection than they verge on the irrelevant. In her preface Butler states that she did her best to include as many women as possible, but this abundance might have benefited from a little judicious curating.

The most obvious example of the effort to leave no one out concerns the two nameless first wives of businessman Charlie Nakamura: both of them hated the Cove and couldn’t wait to get out, and both of them died not long after leaving. Charlie eventually married again, but wife No. 3 seems to have remained in Japan, so she is not part of the Telegraph Cove story. But apart from their very brief and somewhat dubious role is another problem with this vignette about the two earlier wives — and it’s one that goes to the heart of what Butler is trying to do.

In the chapter entitled “Unknown Women Who Died Young,” Charlie Nakamura’s first wives are given exactly two paragraphs between them, and the rest of the chapter, albeit a brief one, is about Charlie himself, who had, the reader learns, a very interesting life. Still, it creates confusion: if this is a book focusing on the experiences of women, why do the men keep showing up and insisting on being included? Butler’s decision to focus on the women is not so much problematic as challenging; there’s just too much story to fit into the box she’s determined to stuff it into, and it keeps spilling out. The end result is that the female-centric approach pulls in women who don’t have much of a role to play, while the men whose lives were inextricably bound up with many of these women consistently refuse to take a back seat, undermining Butler’s stated intent to make this a book about the women.

The observation that Butler has problems managing her cast of characters is not exactly a criticism, because the result, to mix artistic metaphors, is a more expansive canvas consisting of the women themselves, their daughters and granddaughters, and of course the men in their lives. Her goal was laudable, but perhaps it was always going to be a difficult one to pull off. In conclusion, and putting aside any and all reservations, the book is undeniably a wonderful read, and the photographs are outstanding.

There is one more thing to say about this latest history of Telegraph Cove: not about something that’s in the book, but about something that isn’t.

The reader knows that whale watching as a business began in Telegraph Cove in 1979, and that the mill closed down not long after. The end of one era and the beginning of another, one might say. But there’s more to the story. In 1979, Fred Wastell had entered into an agreement to lease land to a couple from Port Alice who wanted to build a campground/RV park and marina. The highway to the North Island had just opened, and Marilyn and Gordie Graham could see an opportunity. When the Telegraph Cove property was sold following Fred’s death in 1985, the Grahams bought the land they wanted from the new owner, including the village itself. Almost forty years later, Telegraph Cove Resorts Ltd. welcomes 100,000 visitors annually and is a major employer on the North Island.

It would be unfair to criticize Butler for not including an account of events since the Grahams became involved with the Cove; after all, it was never her intent to write a general history. On the other hand, some context for the last section of the book, about the development of whale-watching as a major draw for visitors, would have added depth to the stories of the three women she profiles. What we know for sure is that the forty years Butler sidesteps in her book, years during which Telegraph Cove has emerged as an international destination, is a story still to be told.

*

Heather Graham worked as an editor for nearly thirty years, and during that same time made more than one foray into the seductive but fraught business of bookselling. Now officially retired, she indulges her bookish inclinations by taking on the occasional editing project, as well as trying her hand at the storytelling process itself and doing some of her own writing. She lives on Malcolm Island in Queen Charlotte Strait.

*

The Ormsby Review. More Books. More Reviews. More Often.

Publisher and Editor: Richard Mackie

The Ormsby Review is a journal service for serious coverage of B.C. books and authors, hosted by Simon Fraser University. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Robin Fisher, Cole Harris, Wade Davis, Hugh Johnston, Patricia Roy, David Stouck, and Graeme Wynn. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Provincial Government Patron since September 2018: Creative BC

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

Leave a Reply