#577 A trillion to one in Port Alberni

July 12th, 2019

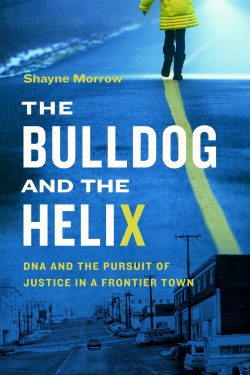

The Bulldog and the Helix: DNA and the Pursuit of Justice in a Frontier Town

by Shayne Morrow

Victoria: Heritage House, 2019

$22.95 / 9781772032505

Reviewed by Kathryn Neilson

*

This book originates from the abduction, rape, and brutal murder of two young girls in the small pulp mill town of Port Alberni on Vancouver Island. The first incident occurred on April 14, 1977 when 12- year-old Carolyn Lee was snatched off a Port Alberni Street. Nineteen years later, on August 1, 1996, eleven-year-old Jessica States disappeared while she was watching a fast-pitch tournament in a local park. The crimes were not related. In The Bulldog and the Helix Shayne Morrow recounts the RCMP investigations and the trials that followed each case from his vantage point as a reporter with the Port Alberni Times and a longtime resident of Port Alberni.

This book originates from the abduction, rape, and brutal murder of two young girls in the small pulp mill town of Port Alberni on Vancouver Island. The first incident occurred on April 14, 1977 when 12- year-old Carolyn Lee was snatched off a Port Alberni Street. Nineteen years later, on August 1, 1996, eleven-year-old Jessica States disappeared while she was watching a fast-pitch tournament in a local park. The crimes were not related. In The Bulldog and the Helix Shayne Morrow recounts the RCMP investigations and the trials that followed each case from his vantage point as a reporter with the Port Alberni Times and a longtime resident of Port Alberni.

This is a different kind of crime story. There is little mystery — both perpetrators were ultimately found and convicted. Nor does Morrow dwell on the horror of the crimes, although photographs of both girls in the book readily elicit the outrage and grief that such evil evokes. Instead, he effectively uses the two crimes to bookend an account of the scientific and legislative developments that led to the use of the double-helixed molecule known as DNA (deoxyribonucleic acid) in Canadian forensic investigations.

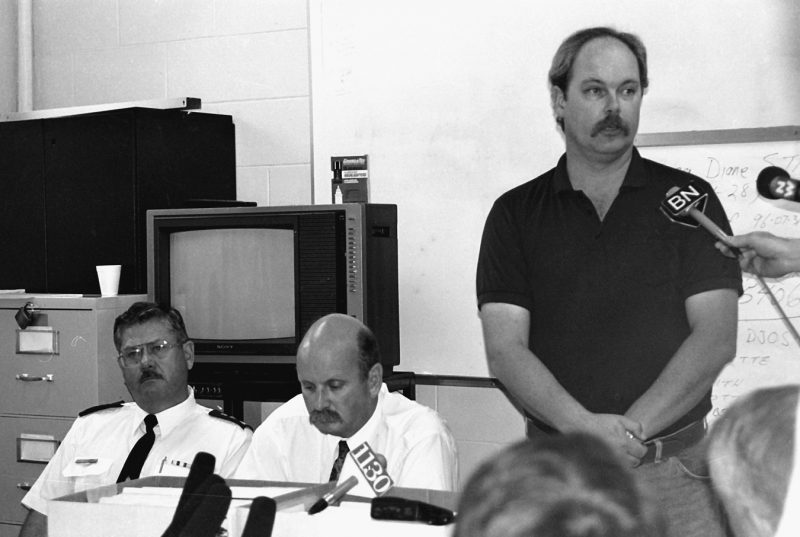

Morrow’s primary focus is the pioneering role played by local RCMP officers and laboratory scientists in this evolution, notably Cpl. Dan Smith, the “bulldog” of the title. Smith took over the Lee file as a cold case in 1988 and pursued it for nine years, ultimately employing DNA evidence to convict her murderer. He then put this experience to use in identifying States’s assailant. In the process Smith became a lay expert in the emerging DNA technology, and accomplished several “firsts” in its use.

The town of Port Alberni emerges as an underlying motif. Such heinous crimes have an impact wherever they occur but these were “big-town crime[s] in a small town” (p. 75). The book opens with a map and a detailed description of the town. Later, Morrow periodically interrupts the narrative with vignettes of its citizens, its boom-and-bust history, and its criminal element. Not all of these diversions have relevance to the crimes at hand but they do provide context and evince Morrow’s intimate knowledge of his community.

His position as a court and crime reporter in Port Alberni from 1994 to 2011 served Morrow well in writing The Bulldog and the Helix. He clearly developed a close relationship with the local RCMP, and used this to gather information and report on the Lee and States investigations and on the trials that followed. As well, he amassed a large archive of newspaper reports, his own and others’, which, along with extensive interviews of the main players and archival research, have produced a detailed and realistic reconstruction of these two disturbing cases.

It is now generally known that analysis of an individual’s DNA creates a genetic “fingerprint” unique to that person. Morrow does a creditable job of explaining the complex scientific process that underlies that statement, although the details of cell structure and its analysis may be difficult for lay readers to fully grasp. He more easily explains the steps that were necessary to create useful DNA evidence in these cases. The police recovered vaginal swabs from both victims that contained their assailants’ semen. A DNA analysis of these semen samples could produce unique genetic profiles of these unknown men. This only became useful, however, if a suspect was identified and provided a sample of his DNA for analysis and comparison to the perpetrator’s profile. The police could obtain a sample from a suspect with his consent, with a warrant setting out reasonable and probable grounds to seek the sample, or from DNA cast off by the suspect on something like a coffee cup. If comparison of the samples revealed a match, the result would be reported as the statistical odds that someone other than the suspect would match the DNA from the crime scene.

In both the Lee and States cases the police obtained voluntary DNA samples from the suspects. Concerns arose later that these might not be admissible at trial because they were obtained without fully advising them of their rights. While readers familiar with the law will understand Morrow’s references to an “‘uninformed consent’ defence” (p. 58) or the “grey area” of consent samples (p. 65) created by the Supreme Court of Canada’s decision in R. v. Borden, [1994] 3 S.C.R. 1450, others might have benefitted from a fuller description of the concept of informed consent and the difficulties presented by its absence.

The efforts of Cpl. Smith and his colleagues to employ the emerging DNA technology in the Lee case are central to the book. Smith learned by happenstance from a magazine article that DNA had been used to solve two murders in Britain in the late 1980s, and that Joseph Wambaugh had written a book, The Blooding, about this case. His research convinced him DNA analysis could solve the Lee case. The RCMP had the semen sample from Lee’s assailant and, shortly after her murder they had identified a possible suspect, Gurmit Singh Dhillon, from evidence recovered at the crime scene. Smith set about arranging a DNA analysis comparing the semen sample to a DNA sample from Dhillon.

Morrow recounts the disappointing results of early analyses. The Restriction Fragment Length Polymorphism (RFLP) process of DNA typing available to the RCMP was not sensitive enough to reveal a genetic profile of Lee’s killer from the degraded semen sample. In 1992, with help from the Vancouver Serious Crimes Unit, Smith nevertheless obtained a DNA sample from Dhillon, who unexpectedly provided it voluntarily. RFLP analysis of Dhillon’s sample and the semen sample was again disappointing, producing an “inconclusive” result. Undaunted, in 1993 and 1994 the investigators sent these two samples to laboratories in North Carolina and Washington that had a newer and more sensitive DNA system, Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR). While these analyses both detected a match between the samples the most favourable result found the statistical odds that someone other than Dhillon would match the semen sample was only one in thirty-four hundred, a level too weak to support charges.

As these analyses proceeded, judicial decisions began to shape the law governing the forensic use of DNA. Morrow recounts that in 1995 Parliament responded by enacting Bill C-104, now s. 487.04 ff. of the Criminal Code. This provided that on reasonable grounds being shown a judge could issue a warrant compelling a suspect to provide a DNA sample. In March 1996 Cpl. Smith successfully executed Vancouver Island’s first “DNA warrant” on Dhillon, alleviating concerns that the earlier consent sample might not be accepted at trial. This new sample and the semen sample were analyzed using the PCR method at the RCMP’s Ottawa laboratory. The result was improved but still insufficient odds of one in thirty-eight thousand.

Unwilling to give up, the “bulldog” postulated that a combination of the results from the three PCR analyses in Ottawa and the two American laboratories might increase the odds. An expert analysis in Texas proved him right. This aggregate analysis produced odds of one in one-hundred-and-sixty-five million. The Lee case became “Canada’s first historic DNA cold case” (p. 1). Dhillon was arrested and charged with first degree murder on March 14, 1997.

Morrow turns to Jessica States’s murder. By 1996 DNA was being routinely used in criminal investigations. The Bulldog and the Helix recounts that the Port Alberni RCMP and RCMP laboratory scientists nevertheless accomplished another DNA benchmark in her case: the first successful Canadian “blooding.” DNA analysis of the semen sample recovered in States’s case had provided a genetic fingerprint of her killer, but the police had not identified a suspect. With characteristic determination Smith and his colleagues orchestrated a “genetic manhunt” (p. 79), soliciting voluntary DNA samples from Port Alberni residents and the ballplayers who had attended the fast pitch tournament near the scene of the crime.

By 1998 over 400 samples had been collected and sent to the RCMP Forensic Laboratory in Vancouver for analysis. Progress was slow due to the volume, and Morrow takes pain in describing the elation when, on June 23, 1999, one of the last samples provided a match to Roderick Patten, a young Port Alberni resident with a troubled past. The reported odds of some other person being the murderer were1.9 trillion to one. Patten was charged with first degree murder, arrested, and confessed to the crimes.

Morrow’s accounts of the Dhillon and Patten trials are so complete that my first impression was he must have been present. A closer reading reveals this was not the case, and he has instead done an admirable job of providing detailed and authentic accounts of the proceedings from his array of sources.

Editorial limitations preclude a complete account of the lengthy trials in each case. Briefly, both offenders were tried before a judge and jury. Dhillon attacked the validity of the DNA evidence, claiming he was framed and wrongly accused. The DNA evidence was thus central at his trial. Patten’s confession obviated the need for DNA evidence in his case. He defended on the basis that a bad LSD trip had rendered him mentally deficient when he committed the crimes and he should therefore be convicted of the lesser offence of manslaughter. Both cases had some unexpected twists. There is a particularly interesting account of contempt proceedings brought against a defence expert witness at the Patten trial. Each jury ultimately brought in a verdict of first degree murder. Dhillon and Patten were each sentenced to life imprisonment.

In short, The Bulldog and the Helix is a worthwhile read about two horrific crimes, and the determination of RCMP officers in the small Port Alberni detachment to bring the perpetrators to justice. Morrow properly singles out Cpl. Smith for his ingenuity and patience in pursuing DNA analysis to solve the crimes, and accomplishing several “firsts” in the process.

I venture one criticism. The central story is often interrupted to recount other crimes. Some occur in Port Alberni, some elsewhere in British Columbia; some are interesting, others disturbing. The Clifford Olsen and Willy Pickton cases make an appearance, as does the 9/11 terrorist attack in New York. Some of these diversions may be intended to enhance the background of the officers and scientists in the Lee and States cases, but I found most were unnecessary distractions.

The Bulldog and the Helix will undoubtedly appeal to Port Alberni residents, who should be justifiably proud of the job done by their constabulary. It will also be of interest to residents of Vancouver Island and beyond who enjoy realistic crime stories. As well, DNA has become well-known in the general population and the book will appeal to those interested in its history and potential in criminal investigations.

In an epilogue Morrow reports on developments in DNA since these investigations took place. Many historical cases have been solved using DNA. Increasing sensitivity in the scientific process has led to greater precision, but has also introduced greater risks of contamination by inadvertent contact. The DNA Identification Act, which came into effect in 2000, created the National DNA Data Bank in which DNA profiles from crime scenes and from offenders convicted of designated offences are stored for future analysis and comparison. Police in the United States have recently, and with some success, turned to public genealogy websites to expand the cohort of DNA samples available for matching in criminal investigations, a practice that will inevitably come to Canada and raises interesting ethical and legal questions related to the unassuming donors.

While the “bulldog” and his colleagues deserve recognition for their early leadership in the field it is clear a full story of DNA’s potential in criminal cases remains to be discovered.

*

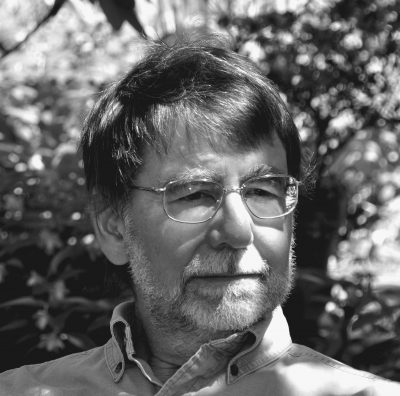

Kathryn Neilson is a retired lawyer and judge. Her legal career in Vancouver included government service as Crown Counsel, as well as private practice in civil litigation and administrative law. She was a part-time adjudicator for the B.C. Human Rights Tribunal, and also worked in the field of international human rights in South Africa and in Cambodia, where she spent a year with the United Nations as a human rights officer. She was appointed to the Supreme Court of British Columbia in 1999, and to the B.C. Court of Appeal in 2008, retiring in 2016. Ms. Neilson has served on a number of professional and community boards and committees. During her career she periodically taught part-time at the law schools of U.B.C. and the University of Victoria, and in the Department of Criminology at Simon Fraser University. She was also engaged in continuing legal education courses for lawyers and judges. She has published papers on diverse legal topics and on her experiences in Cambodia.

*

The Ormsby Review. More Books. More Reviews. More Often.

Publisher and Editor: Richard Mackie

The Ormsby Review is a journal service for serious coverage of B.C. books and authors, hosted by Simon Fraser University. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Robin Fisher, Cole Harris, Wade Davis, Hugh Johnston, Patricia Roy, David Stouck, and Graeme Wynn. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Provincial Government Patron since September 2018: Creative BC

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

Leave a Reply