#569 Superscript and sexual tension

June 30th, 2019

Reproduction

by Ian Williams

Toronto: Penguin Random House Canada, 2019

$35.00 / 9780735274051

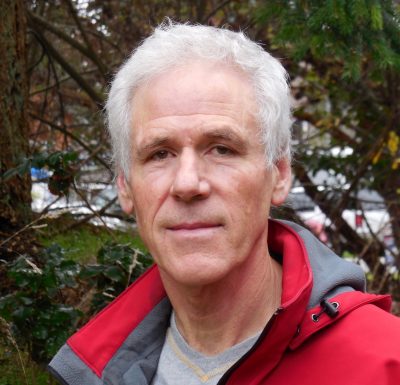

Reviewed by Theo Dombrowski

*

Of his recent novel, Reproduction, Ian Williams says “…it should be read like a good love story. That’s the only thing I want to read and write, or care about in people’s lives.”[1]

Of his recent novel, Reproduction, Ian Williams says “…it should be read like a good love story. That’s the only thing I want to read and write, or care about in people’s lives.”[1]

For any reader feeling at odds with our complex and carnivorous world, such an accessible, universal, and, above all, human subject, should be reassuring. Up to a point, it is. Although issues like the Nazi holocaust and colonial poverty lie in the background of the novel, it is largely in the background that they stay.

Many of our best novels, of course, can be considered love stories, from Pride and Prejudice through Ulysses to contemporary novels by Booker Prize winners, like Anne Enright’s The Forgotten Waltz. Any readers who approach Williams’ novel as a love story, however, should approach with broadened expectations and girded loins.

The title itself should tell them this. Reproduction? A novel about love? The discrepancy between (biological) reproduction and (traditional notions of) love plays and replays throughout the novel. This discrepancy between what we might expect of a love story and what we get underpins both form and content.

First, the form: claiming that this novel has something in common with Ulysses has a point. It has become something of a truism that Joyce’s “modernist” experiments in expanding narrative techniques largely led to a dead end. Few novelists in the century since the publication of Ulysses have attempted very much in the way of technical inventiveness. Those readers who approach Reproduction with an appreciation of James Joyce’s famous — and infamous — landmark novel may, however, find themselves perking up at points.

Readers of Joyce can hardly help noticing, for example, that in this book there is a chapter constructed very like the so-called “Aeolus” chapter of Ulysses. Like Joyce’s chapter, this one is made up of small chunks, each headed by a title, some like newspaper headlines, some mere expletives, some cheerfully whimsical commentary, and so on. Williams, however, has numbered his chunks. Why?

Joyce cheated a little in making sure his narrative ingenuity was properly recognized. He used his friend Stuart Gilbert as a conduit for letting his readers know what they would be unlikely to observe, a complex scheme of analogies, symbols, and correspondences (purportedly) underlying the novel. Williams, in turn, has used several interviewers to do something similar:

I wanted to write a book that would reproduce itself, so it’s in four parts and each part approaches reproduction differently. In part one it’s biological. It’s in 23 paired chapters so it’s chromosomal. Part two has four characters, so we go from those two characters to four characters and 16 chapters. And part three [grows] exponentially, from 16 to 256 small sections.

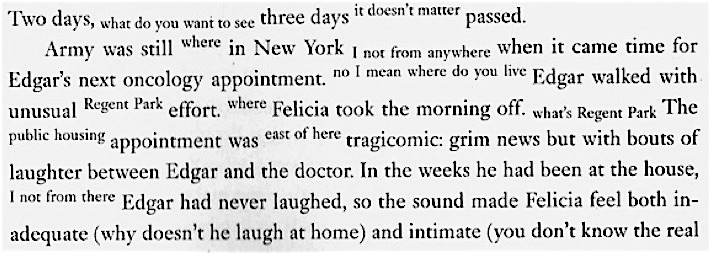

At the end of part three the book gets cancer and you see those tumours growing in the superscript and the subscript [rendered by the text flowing intermittently above, below, and along the sentence lines]. That is the final form of reproduction beyond human control.[2]

Of all these techniques the last is by the most striking. As is the case with all of the techniques, however, a reader would be forgiven for not clicking on its intended implications. Like cancer? Who would have thought?

Let’s linger a little on this particular technique. It is easy (and often effective) to skip over the super and subscripts the first time through a paragraph, and then read them separately so that the parallel streams (largely) cohere. However, reading the fragments in the order they are actually printed can make for some pretty heavy sailing. Amongst other things, the extra lines of text differ — some are like a parallel stream of thought, some are recollected dialogue, some are almost like a choric commentary, and so on.

The technique is a good reminder that conventional “stream of consciousness” is not a very accurate replication of how the mind works. Far from functioning as a single sequence, thought often comprises (as some of Williams’ supertexts suggest) simultaneous parallel sequences, what late in the novel he calls “a matrix of thoughts.” The fact that words on a page, which need to be read one at a time, don’t actually allow double or triple interpenetration of thought is a limitation of writing, a medium which can’t possibly reproduce the way thought works.

This particular innovation is the most audacious: most of the other technical experiments are accessible, and, arguably, successful. Numbered lists, daybook entries, telephone conversations, exchanges of letters or texting — even a diagrammed church service with text in floating boxes — are often stimulating and affecting. Probably the most appealing of these are the chapters of pure dialogue headed “Sex Talk.” Much of the narration, in fact, is in one form of dialogue or another, principally with two characters at loggerheads. In these chapters, however, Williams uses nothing but dialogue. The results are hugely entertaining, though in large part because of the spark and play of personality, language and perception rather than the form itself.

Does all this inventiveness have a real narrative point? Possibly not. Does it, however, reflect a writer for whom the very form of the novel is a major element, for whom craft is as important as any other aspect? Apparently, yes. Arguably, too, the reader is forced to be aware both of the “real” sequence of events beyond the words and, simultaneously, the filter through which they come, a filter which points to the purely conventional nature of common narrative methods. Viewed this way, the book is, in part, about the very act of “reproducing” the (fictional) world.

Even when the narrative development is more or less straightforward Williams never relaxes. At its best, the style is nimble, inflected with darting fragments, almost of stream of consciousness, flickers of observations — and often little odd ball observations that the reader is unlikely to have read anywhere before: “Felicity noticed that Edgar … adjusted his underwear through the pocket…. She should buy him some jockey shorts that fit. Three in a pack from Simpsons.”

At times seeming almost arbitrary, maybe out of control, these darts and feints also reveal scrupulous care — much of it evident on a rereading. Thus, for example, Williams inserts the phrase “digitally penetrated” very early in the novel where it is barely noticeable. On a single reading few readers are unlikely to remember the phrase when very much later it reappears at the vortex of a narrative whirlpool. More clearly resonant are gestures that repeat at intervals. Williams himself points out, interviewed, the significance of a thumb rubbed on a forehead. Readers themselves will notice the number of times, likewise, biologically related characters reproduce the gesture of clasping their forearms.

Most striking in terms of the flex and play in the narrative development, though, is the deft way that Williams leaps forward in time, disorienting us in a suddenly unintroduced context of detailed thoughts and characters, only later filling in helpful information. Thus we are made to feel that time itself is as fluid and shifting as are the contrary points of view through which we experience thought and perception.

All such writing testifies very much to the fact that, as a “love story,” Reproduction is not exactly mainstream.

As for the storyline, William likewise comes to the game from left field. Developed in four chunks, each separated by many years, the novel does, appropriately, feed off relations between males and females. Felicia, a young Caribbean woman, in the opening chapters, meets Edgar, a German businessman, in a hospital room shared by their failing mothers. Many years later, their illegitimate son, Army (short for “Armistice” as we eventually learn) develops flamboyant ardor for his landlord’s daughter, Heather, while she, in turn, broods painfully over a goth-posturing, Zellers-employed bandboy, “Skinnyboy.” The landlord, Oliver, has his own sexual tensions, both with Felicia and, very differently, with his ex-wife. Later, his teenaged grandson, “Riot”, (short for “Chariot”), in turn exhibits (quite literally) his — by way of an online masturbation video that shocks his girlfriend.

It doesn’t take a die-hard romantic to recognize immediately that this isn’t the stuff of an easily recognizable love story. However, insofar as “reproduction” can be considered as an aspect of love, the novel somewhat lives up to its name. Characters do have babies in the course of the novel — though the baby count is low: Oliver has two, Felicity has one, and Heather one. More directly, the key word, “reproduction,” pops up regularly and noticeably: “not everyone should reproduce,” Army assures Riot at one point, for example. Running loose with the notion of reproduction, some readers might surmise that young Riot’s obsessive videotaping huge, unedited dollops of daily life is about (videographic) “reproduction.”

Rather than being about either lover or reproduction, the novel seems centrally about the mottled and myriad worlds of sexual behaviour. Consider: One scene of sexual tension early in the novel leads to a thwarted knife attack and, in response, a failed rape attempt. In the course of the novel, amongst the six chief characters, one is aggressively seduced and impregnated, one is involved in accusations of work-site sexual harassment, one suffers drug-laced date rape, one is mired in a life time addiction to lap dancing, and one faces charges of online pornography. Not just background noise, all of these are deeply imbedded in the narrative.

Pointedly, too, Williams makes considerable hay from wryly mirroring social codes surrounding much of this sexual behaviour. In one generation, for example, he delights in giving us fatuous contemporary courting teen-chat between Heather and her gauchly self-absorbed bandboy, his eloquence limited to utterances of “Mmrm,” “Murmur,” and “Coo.” At another, he erects a vast superstructure of politically correct indignation over Riot’s ridiculous online masturbation video, thereby (in Oliver’s terms) infringing on “a sensitive cultural moment regarding assault.” Edgar’s own forced resignation over what, in current terms, is sexual harassment, likewise smacks, knowingly, of contemporaneity.

More profoundly, though, Williams draws us into a human web of emotional interconnectivity that has little or nothing to do with any of sexual behaviour, reproduction, or, in the romantic sense, love. Movingly, Williams himself has said, “When you’re forced to be with people… you realize life is better for it. I’m perpetually fascinated by how strangers become family.”[3]

Towards the end of the novel, Felicia reflects on the children, children’s children, and men who have loosely assembled themselves around her, quietly asserting her achievements and strengths, drawing consolation from the simple, controlled fact that “she prepared nutritious breakfast for her household (this was her preferred term for the group though everyone else in the household called themselves a family….”).

Though, in the eyes of the author and the media, the novel is essentially about such relationships, Reproduction will make its biggest impact for many readers as a novel of character — or, more specifically, characters, and two characters in particular. All the characters are colourful, all slightly larger than life (with the possible exception of Hendrix, Felicia’s second son). Still, the two older men, Edgar and Oliver, are a little hard to take. It shouldn’t count for much that one does math problems in his head while witnessing, as he thinks, his mother’s death, and that the other is a failed math teacher. But it seems to. Capable of generosity and acts of tenderness, yes, both nevertheless are essentially hard, self-absorbed, aggressive, and even violent. Oliver’s daughter, Heather, and grandson, Riot, are a little more engaging, but are, when they play central parts of the narrative, too much swaddled in their adolescence to break free into much individuality. Felicia, however, and her son, Army, are quite another kettle of fish.

Williams seems to be just a little in love with these two. And for good reason. In different ways, both are vital, emotional, courageous — and a little manic. Both, too, manage to be sympathetic, outrageous, hilarious, and maddening. With her emotional monitor hovering between indignation and embitterment, her language unfailingly sarcastic, Felicia dishes out “the dialect of her small unrecognized island” the same way she dishes out a stream of invective or yet another grim tale of life on that “small unrecognized island.” Returning to the hospital and her dying mother, Felicia is told that the hospital tried to reach her. Her response? “Nobody tried to reach me…. You mean to tell me in six hours, she counted out with her fingers, twelve, one, two, three, four, five o’clock, nobody could reach me? I is not the Queen of England. I don’ have no secretary. You dial the phone and you reach me.” This nineteen-year-old version of Felicia doesn’t fade a whit throughout the novel.

Likewise, the word “irrepressible” seems to have been invented with the express purpose of describing Army — as a small child, an adolescent, and a thirty-six- year old man, it hardly matters. At his most nimble during his adolescence, Army has two obsessions — making money with one far-fetched venture after another and, second, trying to manoeuver into Heather’s affections. No wan wooer, “he would always love her with the high, delirious pitch of Whitney Houston” (p. 175). In attaining neither goal does he succeed, but he remains … irrepressible. In telephone sparring with Edgar, the father he has never met, he refuses to be fazed: “Boss, easy on the yo-mamma business,” he cheerfully warns at one point, and, at another, waves off Edgar’s emotional insistence by announcing, “my mojo’s all messed up with this energy.”

As Williams reveals late in the novel, though, Army’s obsession with money comes from somewhere painful, his lingering fear of the poverty he felt as a child. The particular case of Army reveals, in turn, much about Williams’ construction of the novel. Patiently planting hints and suggestions early on, he torques up the narrative energy as the novel nears its end and he makes one revelation after another — usually without much fanfare.

Thus, for example, Edgar’s mother, as we learn partly in tiny fragments of superscript, was only pretending to be German — and the circumstances surrounding her deception darken and tighten much of the novel’s concern with race and identity. Likewise, Heather’s disturbing sexual experience as a girl is given its rawest and most explicit form only in a conversation with the adult Army: “After I came back home … you said the worst thing anybody has ever said to me.” Most dramatically, perhaps, and but a few pages from the end of the novel, Williams reveals why so much unspoken sorrow surrounds even the faintest reference to Hendrix — and makes the revelation in six words enclosed in parentheses.

And of Hendrix, Oliver thinks, “So why so much Sturm und Drang over one … when 70,000 die in Sichuan? Over two deaths when 250,000 die when the tide suddenly disappeared? Over three deaths.” Oliver, the former math teacher, thus, a little stupidly, touches on the central power of the whole novel. It is not about 70,000 or 250,000. It is about a few people in an inconsequential Ontario city. Army’s thoughts of his own mother are poignantly similar: “No one took note of her. She’d die and disappear. Never thought of by strangers. Like the vague deaths of an earthquake. His mother was one of ordinary billions.”

Felicia is, of course, exactly that — one of ordinary billions. The same is true of every character in the book. And yet, in extraordinary ways, Williams has given their ordinary lives extraordinary resonance. In a novel confined to the experiences, emotions, and thoughts of a handful of characters, their interconnectedness largely accidental and arbitrary, Williams has given texture, depth … and meaning … to the one thing that, as he says, truly matters to him,” the only thing I want to read and write, or care about.”

*

Born on Vancouver Island, Theo Dombrowski grew up in Port Alberni and studied at the University of Victoria and later in Nova Scotia and London, England. With a doctorate in English literature, he returned to teach at Royal Roads, the University of Victoria, and finally at Lester Pearson College at Metchosin. He also studied painting and drawing at the Banff School of Fine Arts and at UVic. Theo is the author and illustrator of popular guide, travel, and hiking books including Secret Beaches of the Salish Sea (Heritage House, 2012), Seaside Walks of Vancouver Island (Rocky Mountain Books, 2016), and Family Walks and Hikes of Vancouver Island — Volume 1: Victoria to Nanaimo, and Volume 2: Nanaimo North to Strathcona Park (Rocky Mountain Books, 2018). Theo lives at Nanoose Bay.

*

The Ormsby Review. More Books. More Reviews. More Often.

Publisher and Editor: Richard Mackie

The Ormsby Review is a journal service for serious coverage of B.C. books and authors, hosted by Simon Fraser University. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Robin Fisher, Cole Harris, Wade Davis, Hugh Johnston, Patricia Roy, David Stouck, and Graeme Wynn. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Provincial Government Patron since September 2018: Creative BC

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

Endnotes:

[1] Suzanne Alyssa Andrew, “Poet Ian Williams experiments with structure to tell a classic love story,” Quill & Quire (January 2019): https://quillandquire.com/authors/poet-ian-williams-experiments-with-structure-to-tell-a-classic-love-story/

[2] Andrew, “Poet Ian Williams experiments.”

[3] Andrew, “Poet Ian Williams experiments.”

Leave a Reply