#559 Playing saxophone at Ponoka

June 09th, 2019

Playing into Silence

by Tina Biello

Halfmoon Bay: Dagger Editions, 2019

$18.00 / 9781987915785

Reviewed by Phyllis Reeve

*

Narrative poetry often seems autobiographical even when we know it isn’t. Perhaps poetry is by definition more intense, concentrated and personal than prose. Tina Biello’s two previous books of poetry, In the Bone Cracks of the Walls (Leaf Press Spring, 2014) and A Housecoat Remains (Guernica Editions, 2015) are frankly personal, drawing on family relationships and origins.

Narrative poetry often seems autobiographical even when we know it isn’t. Perhaps poetry is by definition more intense, concentrated and personal than prose. Tina Biello’s two previous books of poetry, In the Bone Cracks of the Walls (Leaf Press Spring, 2014) and A Housecoat Remains (Guernica Editions, 2015) are frankly personal, drawing on family relationships and origins.

We can’t be so sure about the narrative in Playing into Silence, the most recent slim volume from Nanaimo’s Poet Laureate.

The protagonist, Pam, is a generation older than Biello. Her hometown setting, Heisler on the Alberta prairies, is not Biello’s. That would be the logging community of Lake Cowichan on Vancouver Island.

Heisler’s website offers “a safe environment for young and old alike … fresh air, open spaces and the opportunity to be a respected community member.” Similarly, a site for Cowichan Lake Community Services boasts of its commitment “to being the best place to raise a child.”

Such protestations of safety could veil different meanings depending on times and attitudes. Heisler was not safe for Pam, nor did it allow her the opportunity to be a respected community member.

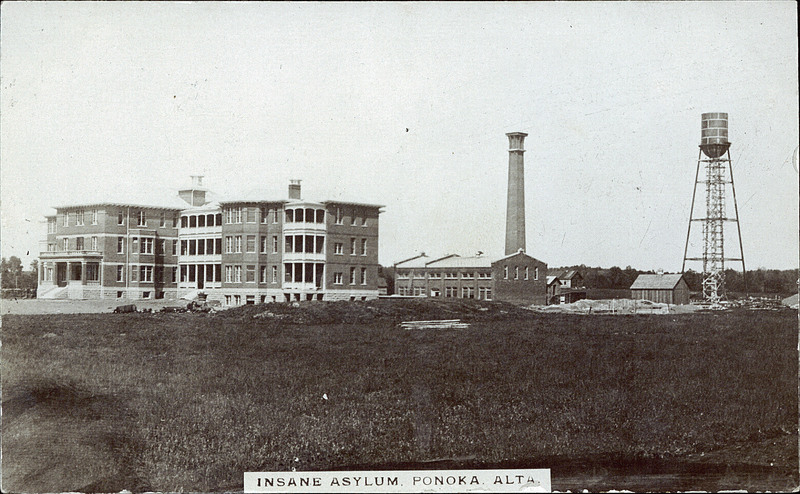

Pam is sixteen in 1965. For a “normal” type of forbidden love she might have been sent to “visit an aunt” or in more severe cases to a reformatory. But homosexuality was something altogether different, definitely not normal, and she is sent to the Ponoka Mental Hospital for the Insane, now the “state of the art” Centennial Centre for Mental Health and Brain Injury.

Two remarkable poems show Pam in the asylum. This is from “1965.”

She plays her saxophone to pass the time.

Indigo notes rise out of the bell, wrap their silky

song around the ears

of the women who sit drugged. A blue-eyed girl

in a wheelchair, in a corner suddenly

stands, waves her arms around like she wants

a partner to fill them, dance her

around the common room….

We learn of private reasons for playing “to save herself” before the conclusion, which gives the book its title:

When the charge nurse takes her saxophone away,

she keeps on playing

into the silence, where the notes

are hers and hers alone.

In “Ponoka,” Pam is again in the common room with her saxophone, a pack of cards for solitaire, and the girl in the wheelchair. The girl wheels herself over to Pam, touches her hair and then her saxophone.

Oh, you do want me to play.

My name is Pam.

What’s yours?

That’s Sheila. I wouldn’t talk to her

or you might find yourself with a black eye.

Nurse moves Sheila away from Pam.

It’s ok, nurse, we were just talking.

I’ll decide what’s ok, dear. You just mind your own business

and keep your game of cards to yourself.

Here, as throughout the volume, Biello makes use of her training in theatre and the art of the mask. Later there is a lover with a clown nose, and I wonder if the author is the lover rather than the protagonist.

Part One of Playing into Silence, “Childhood,” follows the child Pam in the unfolding of her sexual and artistic identity within the closeness and tragedy of a family and small community. The portraits of her parents Lance and Henrietta are surprisingly tender, despite the cruel intergenerational misunderstanding and hints of exploitation. Part Two, “House of Stone,” takes her far afield — to unnamed islands, distant provinces, various lovers, and a “house of stone” across the sea in the Old Country. The reader cannot always be sure which character is Pam. Part Three, “A Good Place” returns an older Pam as a visitor to her sister’s place, to a prairie inhabited with remembered details.

The poem-narrative format allows merging of subjective/ objective more than most prose fiction. The language is rich with emblems: old furniture, old vehicles and machines (it matters which ones still function), a mask, a musical instrument. Consider this poem “To the green chair he sat in every night to watch Jeopardy:”

You held him steady,

even though you rocked a little

while he nodded off

as the wine kicked in.

You took his weight,

Less every year

as his appetite faded.

Only you could touch him. Sometimes

the phone rested on your arm

as he waited for me to call –

I didn’t.

Alone, you consoled him.

After Mom died, he folded

her knot blanket, placed it neatly

on your back, every night.

*

Phyllis Parham Reeve has written about local and personal history in her three solo books and in contributions to journals and multi-author publications. She also contributed the foreword to Charlotte Cameron’s play, October Ferries to Gabriola (Fictive Press, 2017). She is a contributing editor of the Dorchester Review and her writing appears occasionally in Amphora, the journal of the Alcuin Society. A retired librarian and bookseller and co-founder of the bookstore at Page’s Resort & Marina, she lives on Gabriola Island, where she continues to interfere in the cultural life of her community. More details than necessary may be found on her website: https://sites.google.com/site/phyllisreeve/

*

The Ormsby Review. More Books. More Reviews. More Often.

Editor/Designer/Writer: Richard Mackie

Publisher: The Ormsby Literary Society

The Ormsby Review is a journal service for serious coverage of B.C. books and authors, hosted by Simon Fraser University. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Robin Fisher, Cole Harris, Wade Davis, Hugh Johnston, Patricia Roy, David Stouck, and Graeme Wynn. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. As of September, 2018, Provincial Government Patron: Creative BC

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

Leave a Reply