#485 Honouring everyday anxieties

February 13th, 2019

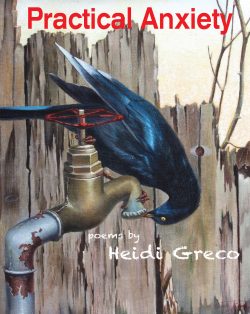

Practical Anxiety

by Heidi Greco

Toronto: Inanna Publications, 2018

$18.95 / 9781771335812

Reviewed by Andrew Parkin

*

Heidi Greco is known already from her previous books of poetry, notably those about Amelia Earhart, A: The Amelia Poems (Lipstick Press, 2009) and Flightpaths (Caitlin, 2017). I enjoyed her live reading from these books in New Westminster last year. Her latest book of poems, Practical Anxiety, is in six parts or sections; this suggests that Greco has read Auden’s Age of Anxiety (1947) that was organized into six “eclogues.” In fact, she quotes from Auden’s book as a sort of preface to her own: “The gods are wringing their great worn hands/ For their watchman is away, their world engine/ Creaking and cracking.”

Heidi Greco is known already from her previous books of poetry, notably those about Amelia Earhart, A: The Amelia Poems (Lipstick Press, 2009) and Flightpaths (Caitlin, 2017). I enjoyed her live reading from these books in New Westminster last year. Her latest book of poems, Practical Anxiety, is in six parts or sections; this suggests that Greco has read Auden’s Age of Anxiety (1947) that was organized into six “eclogues.” In fact, she quotes from Auden’s book as a sort of preface to her own: “The gods are wringing their great worn hands/ For their watchman is away, their world engine/ Creaking and cracking.”

Auden’s title is as striking as those lines recalling the enormous worry of the bare survival of civilization: survival after two world wars and the invention and use of the atomic bomb, linked to the new menace of the communist dictator Stalin’s possession of atomic secrets given to the Soviets by the ideologically motivated scientist spies. The constant anxiety during the “Cold War” has now faded, even with the old KGB man, Mr. Putin, in charge of Russia, territorially the largest country on earth; yet anxiety remains about the possible use of atomic weapons by the leaders of half-developed countries with ambitions to seem very important, or, Heaven forfend, the terrorist groups, if they can get their blood-stained hands on the bomb. These are realistic geopolitical anxieties.

Although Greco has followed Auden’s six-part structure and borrowed his catchword, “Anxiety,” the very real geopolitical concerns still with us are not treated in any detail in her poems. Very recently, our current Prime Minister, M. Trudeau fils, was shown on the TV news referring to “anxiety from global turbulence.” Greco’s anxiety is by contrast low-key. But many of these poems are bright with vivid imagery and finely cut lines. So what are her “practical anxieties”?

In the first section, “A String of Worry Beads,” the opening poem “Oh Dear Angel” presents us with the children’s book characters Dick and Jane, but while all seems normal, their dog is agitated and their guardian angel disquietingly “holds in her fingers a thick cigar, the tip of it hottest orange” (p. 3). We are left to surmise on the dangers of our world for a new generation. In her “Land of the Sugar Plum Fairies” she evokes the fears of a child at bedtime, trying to sleep, but tormented by the idea of her heart as a beating walnut which must be placed within a snowman. Such strange fears are a part of many a childhood, as are injections into the arm by a doctor, “Doc Robin” in her book. A more sinister, unnamed fear, arrives in “Geneses” where her meeting with her cigar smoking uncle ends with “… and I believed.”

Real anxiety, though, is conveyed in the plight of the hidden boy in “Don’t Tell” who cannot escape his hiding place when all the other kids go home. The thoughtless cruelty of children is conveyed vividly also in “Chasing the Light of Fireflies.”

A prose poem, “Cheese Leg,” has vivid images and deals with the child’s fear and dislike of butchers and their shops. As someone who had to learn retail butchering from the age of twelve until I was hauled away into the armed forces at age eighteen, I see this piece as stereotyping the butcher’s shop. The voice is that of a post-war pampered generation who could buy as much meat as was needed and drive away with mom in, luxury of luxuries, the family car. Greco doesn’t tell us whether she ate the meat her mother bought from “loud laughing” butchers in the shop whose smell she couldn’t cope with! Has Greco’s growing girl any sympathy for workers who have to face unpleasant jobs every working day? The final poem in this section on childhood, “Chinook,” depicts a girl facing “the red mistake,” her first period.

The second section, “The Mathematics of Anxiety,” deals with mundane and adolescent worries, such as weight problems. In “The Uncertainty of Machines” she frets at sinister dangers (plumbing nightmares) that I think of as funny, the “change of faucets being reversed,/ installed by left-handed plumbers in a hurry” (p. 19). I am glad I am left-handed myself. It’s a bit of an advantage when playing tennis, badminton, or squash against the right-handed.

In “Big Plans” she thinks of a next life in which she will be a plumber. She doesn’t mention whether she’ll be right- or left-handed but the poem finds at its end a disturbing image, “those taps drip-dripping/ deep inside your skull” (p. 95). Where Greco is fearful of her motor mower in “Hazardous,” I think she’s lucky to have one and a lawn to mow! Many B.C. youngsters today will never be able to afford to buy a house on its own lot.

Meanwhile she is “…overanxious over trying/ to quit smoking…” (p. 21). I could go on listing and pooh-poohing these anxieties of a bourgeois Canadian in a vast country thousands of miles away from the horrors of Africa, the Arab world, and that major terrorist target, Paris (France, not Texas). I could notice her off-hand reference to the fathers of children “…the year we all got pregnant/ with somebody’s baby” (p. 93). Instead I now want to look at the quality of the poems as poetry.

In “Regenerative,” her art as a poet makes us feel the experience of planting bulbs, “each oniony shape,” but there is a moment of uncertainty in the language of the poem. In the second quatrain there is the “conviction that green tips will again suffice.” Suffice? Surely she means “surface,” the word she uses in the last quatrain where “they will surface towards earliest warmth”? (p. 92). It could be a mere typo, but if she really means “suffice” we wait to find out how green tips will “suffice” for what?

This uncertainty causes a bit of reader anxiety. And this reader’s anxiety is aroused by linear verse that lacks music. When verse lacks word music, my reaction is to call it unpoetic verse. In “The Importance of the Bird,” Greco has a list of exquisite things the bird is, but I think her last lines protest too much: “The bird is more than all that matters,/ bird knows sky” (p. 75).

No, it is not more than all that matters. This is a sentimental over-statement. If I saw a bird swooping on a baby in the open air, for example, I would not think the winged predator more than all that matters. I would frighten the bird away to protect the baby. But many of the poems are elegantly poised, as is “Full Moon, April,” where the moon is so bright she can hear it. This Rimbaud-like confusion of the senses works very well.

Her sequence in ten sections, “River of Salmon, River of Dreams” has an attractive fluidity, using a simple vocabulary in which the fish word “milt” appears like a prophecy. Sometimes, as in “Lakeside, Summer Afternoon” she is an accomplished imagist, when she ends the poem with rain hitting the lake to make “tiny wet stalagmites,/ pointing toward sky” (p. 85). In “Even the Starship Enterprise is Being Grounded,” Greco raises the major anxiety of our time, “I worry they’ll remember us/ for ruining the planet…” (p. 78).

There are many very good poems in this volume, some of them prose poems, like “Heaven is Some Place and no Place we Know” (p. 35). But in “Wordsong” she has a poem in brief verse couplets and produces herself “a thing so true/ as morning light” (p. 91).

For me, her best poem, so finely attuned to human experience, is “Prep talks” where we encounter the aged and dying mother without sentimentality but in verse that delivers true feeling and experience: mother

tells me she’s been having long discussions with my dad

my son remarks he hopes

they get along a little better

with shining eyes she tells us

she’s ready to go, hears the rustle,

wings about to unfurl (p. 88)

This I would vote for as the best in the collection.

In “My children still bring prizes for my birthday,” Greco tells us that her children bring her flowers picked from local spots as presents, for “They know that I have everything I could ever need/ so now they bring me flowers” (p. 79). She remembers them as small children bringing dandelions. I don’t worry very much about the anxieties of Heidi Greco now that I know her grown up children don’t seem worried about a mom who has everything she could ever need.

As a book, Practical Anxiety has a wonderful cover of a bird in a parched place where even the tap is dry. The poems are followed by sparse notes, but though she mentions 1432 (near the date of Joan of Arc’s martyrdom), the notes never refer to the date or unlock its significance. Tant pis. Dommage. Among the back cover publicity quotes, I find Anne Simpson and Catherine Owen say just what is needed. I look forward to seeing what Heidi Greco will publish next.

*

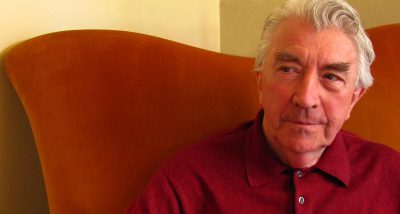

Andrew Parkin was educated in Birmingham at school, and in the RAF Russian programme. After that he studied English at Cambridge and drama for a Ph.D. at Bristol. He emigrated to Canada and taught at UBC before going to the Chinese University of Hong Kong where, with the Chinese-Canadian poet and translator Laurence Wong, he read at the Canadian Consulate and elsewhere on campuses. He retired to Paris and read for the Spring Poetry Festival there and in the “Poets Live” series, before returning to Vancouver with his French wife in 2015. He recently read with Jessica Li from his bilingual Star With a Thousand Moons (Victoria: Ekstasis) in the University of Regina and a few weeks later at York University, Ontario. Meanwhile he is completing a trilogy of novels about counter-terrorism.

*

The Ormsby Review. More Books. More Reviews. More Often.

Editor/Designer/Writer: Richard Mackie

Publisher/Writer: Alan Twigg

The Ormsby Review is a journal service for serious coverage of B.C. books and authors, hosted by Simon Fraser University. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Robin Fisher, Cole Harris, Wade Davis, Hugh Johnston, Patricia Roy, David Stouck, and Graeme Wynn. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. As of September, 2018, Provincial Government Patron: Creative BC

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

Leave a Reply