#438 The Americans are coming

December 03rd, 2018

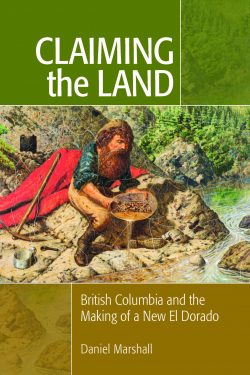

Claiming the Land: British Columbia and the Making of a New Eldorado

by Daniel Marshall

Vancouver: Ronsdale Press, 2018

$24.95 / 9781553805021

Reviewed by Mark Forsythe

*

We are pleased to reprint Mark Forsythe’s review of Daniel Marshall’s Claiming the Land: British Columbia and the Making of a New Eldorado, a book that reveals how Indigenous people, backed up by British colonial and fur trade officials, neutralized lawless paramilitary brigades of American gold miners on the Fraser River in the summer of 1858.

Claiming the Land has achieved a rare and possibly unique feat in BC History by winning three major book awards: the Canadian Historical Association’s 2019 CLIO PRIZE for best book on B.C.; the 2019 Basil-Stuart-Stubbs Prize for outstanding scholarly book on British Columbia, administered by UBC Library; and the 2019 New York-based Independent Publishers’ Book Award (Gold Medal for Western Canada).

This review also appears in the current issue of BC Bookworld (Vol 32, No. 4, Winter 2018-19). — Ed

*

There’s gold dust in Daniel Marshall’s genes. A fifth generation British Columbian, his ancestors journeyed from Cornwall, via the California gold rush, to the next bonanza on the Fraser River in 1858.

There’s gold dust in Daniel Marshall’s genes. A fifth generation British Columbian, his ancestors journeyed from Cornwall, via the California gold rush, to the next bonanza on the Fraser River in 1858.

As a child, Marshall visited the Fraser Canyon with his engineer father to soak up stories of great-great-great Uncle William, a roadway foreman who worked on the legendary Cariboo Wagon Road. He heard other tales of paddle-wheelers, instant tent towns, saloons, and gambling dens. Everyone was chasing “the golden butterfly.”

Later, Marshall became a scholar of gold rush history and came to realize the received wisdom and stories mostly ignored this unsettling fact: during the chaotic summer of 1858, American miners formed militias and went to war with Indigenous people in the Fraser Canyon.

In Claiming The Land, Marshall writes, “There is no doubt that in the first crucial year of the gold rush, the Fraser River was an extension of Californian mining society and fell clearly into the orb of the tumultuous American West and its Indian Wars.” In other words, “A good Indian is a dead Indian.”

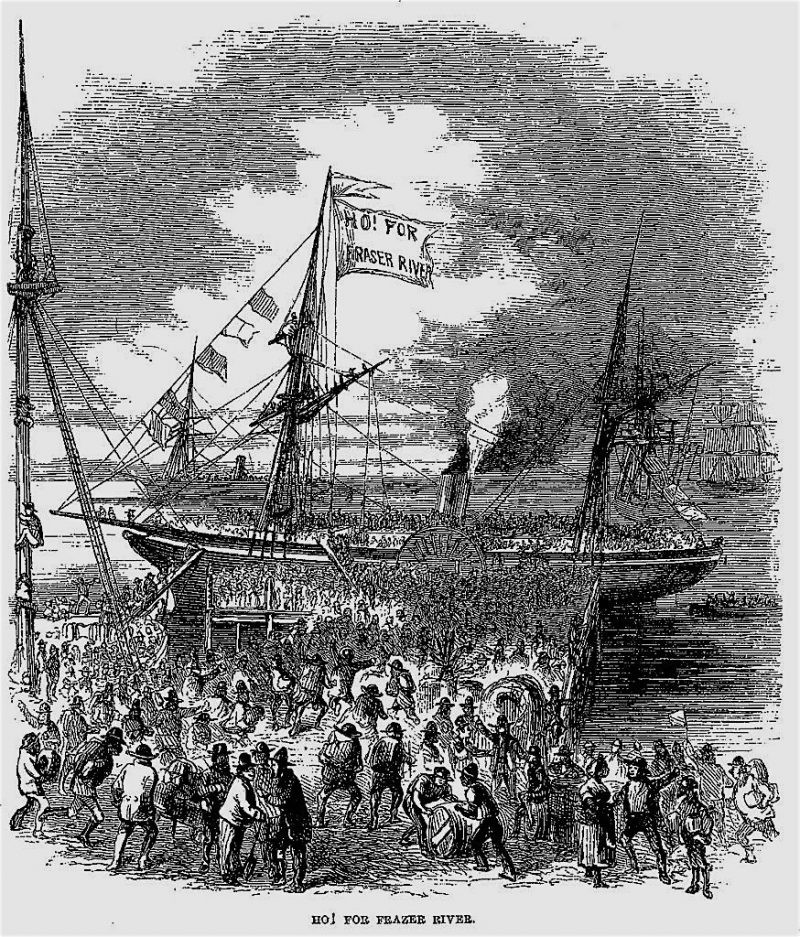

San Francisco, summer 1858: a ship full of eager gold miners departs for Victoria and Fraser River. Illustration by J. Ross Browne from Harper’s Monthly Magazine, December 1860

The gold rush is regarded as the founding event for British Columbia, spurred on by early newspaper headlines in Oregon and California in the spring of 1858. THE FRAZER RIVER GOLD MINES – GREAT EXCITEMENT.

Marshall writes, “The press reports went on to say that Indigenous women were panning out $10 to $12 of gold a day. To the patriarchal world of white California, news of Native women accruing such wealth encouraged the notion that gold on the Fraser River was easily obtainable.”

Word spread throughout the US, eastern Canada, Europe, and beyond.

The Fraser River gold rush was the third great mass migration of gold seekers that the world had seen, following rushes in Australia and California. A glance at a Fraser Canyon map from 1858 illustrates just who was doing most of the panning at Ohio Bar, Sacramento Bar, Washington Bar, American Bar, New York Bar, Fifty-four Forty Bar, Boston Bar, Texas Bar, and others.

At least 30,000 Americans swept north across the 49th parallel, by sea and overland; some argue it was actually thousands more because there was no colonial authority on the mainland at the time. However, the Hudson’s Bay Company (HBC) was on the scene, conducting a fur and salmon trade with First Nations partners; indeed, HBC had previously bought gold from Indigenous people. They had discovered the gold, and were the first miners.

The California 49ers were coming from — and through — a region aflame with what were known as Indian wars. The US Military was clearing a corridor in a campaign of extermination. At first there was an “unspoken detente” north of the 49th between Indigenous people and the miners, but as the rush moved higher into the Thompson region, conflict erupted.

Headless bodies of miners floated the Fraser River. At least five native villages were torched by militias. In one engagement 36 natives were killed, five Chiefs among them. During an interview Daniel Marshall recounts digging deep into US archives in the Pacific Slope region to uncover more about this little-known war:

Quite a number of my professors poo-pooed this notion, but I started to accumulate the kind of evidence that was never featured in the colonial correspondence for the Colony of Vancouver Island or British Columbia. Where did those miners send their letters, and samples of Fraser River gold? Where did their diaries end up? All south of the border. It’s in those collections that you find greater and greater evidence for this Fraser Canyon War in 1858.

Daniel Marshall with statue of Governor James Douglas at Fort Langley, fall 2018. BC Historical Federation photo

Unlike conditions for the California rush, the Hudson’s Bay Company provided something of a buffer between the miners and native peoples. Chief Factor James Douglas wore two hats, as the head of the HBC’s Board of Management in Victoria and as the Governor of Vancouver Island. At first, Douglas wanted to stop Americans from coming into B.C., but was overruled by the Colonial Secretary who wasn’t eager to hazard another war with the US.

Douglas did his best to assert British authority on the mainland. The Nlaka’pamux were accustomed to trading furs, fish, and gold with the HBC, not being forced off the river and out of the picture. At one point they completely shut down the gold rush on Fraser River. Miners retreated to Yale, others returned for good to California.

“This ultimately caused miner militias to be formed,” says Marshall. “Thousands were called together to elect their military officers to go up the canyon.”

Captain Henry Snyder of San Francisco attempted peace treaties with Indigenous groups and got as far as Spuzzum, where he discovered the Whatcom Guards were intent on killing every Indian man, woman, and child. Mysteriously, the Guard’s two leaders were killed in the night, effectively ending this exterminationist campaign.

Snyder was later successful in negotiating a peace with Chief David Spintlum (Cexpe’nthlEm, 1812-1887, now regarded as the greatest chief of the Thompson First Nations Peoples in recent times), who understood the bigger picture: violence to the south was wiping out Indigenous people. Marshall thinks a larger war would have ended badly:

Monument in Lytton to Chief Spintlum, credited with countering American campaigns of extermination on the Fraser River

160 years ago, if James Douglas wasn’t there and Indigenous people hadn’t fought back, this could very well have become part of the USA. American troops would have come into the Fraser Canyon with howitzers.

Claiming the Land further explores the three main cultures of 1858 — the doomed fur trade, Californian, and British. Marshall makes an argument that the gold rush, with its north/south flow, precipitated the need for an east/west Canada to the Pacific that came to be in 1871. “Manifest Destiny” was never far way and the British and then Canadian governments had to build secure east/ west institutions.

Marshall, now an adjunct professor of history at the University of Victoria, reminds us how everything changed for Indigenous peoples in 1858 — something we continue to grapple with today.

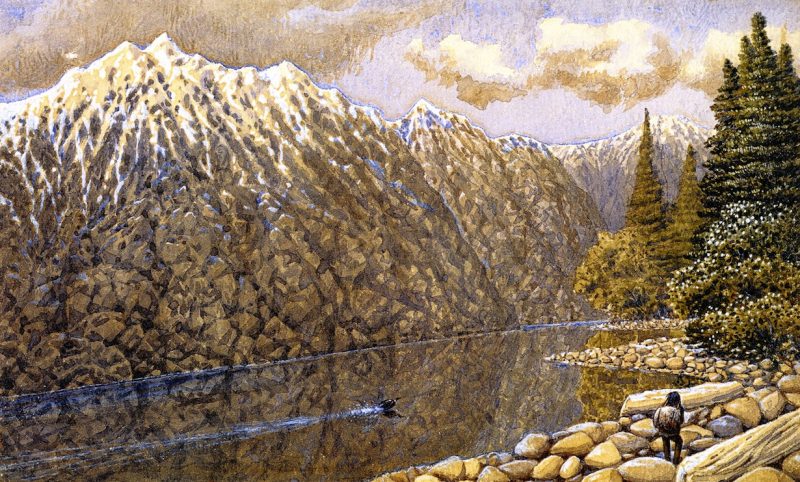

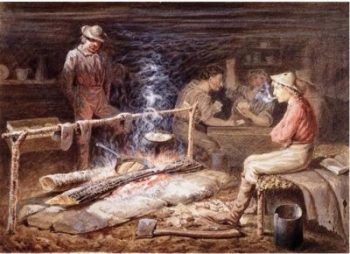

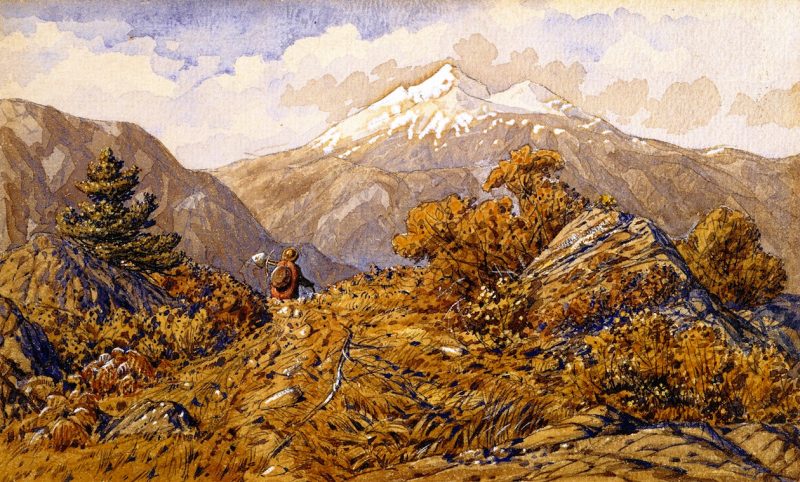

Indigenous packer and loon on the Fraser River, painted by William Hind circa 1862. McCord Museum, Montreal

*

Mark Forsythe spent his youth in Ontario, two years in Quebec, then landed his first radio job at CFBV Smithers in 1974. He later joined CBC Radio at Prince Rupert in 1984, moved to Kelowna to help establish a new CBC bureau, and joined CBC Vancouver in 1989, hosting CBC Radio current affairs programs, including BC Almanac for 18 years until he retired from the CBC in 2015. Along the way, Mark co-authored four books with listeners about BC history, culture, and recreation, including (both co-authored with Greg Dickson), The Trail of 1858: British Columbia’s Gold Rush Past (Harbour, 2007), and From the West Coast to the Western Front: British Columbians and the Great War (Harbour, 2014), which won the Lieutenant-Governor’s Medal for Historical Writing. Mark knew he was truly retired after receiving a Lifetime Achievement Award from the Radio & Television News Directors Association. He lives in historic Fort Langley, where he volunteers with the Langley Heritage Society, sits on the council of the BC Historical Federation, does freelance journalism work, and dreams of more travel adventures in B.C. with his wife Cat.

*

The Ormsby Review. More Books. More Reviews. More Often.

Editor/Designer/Writer: Richard Mackie

Publisher/Writer: Alan Twigg

The Ormsby Review is a journal service for serious coverage of B.C. books and authors, hosted by Simon Fraser University. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Robin Fisher, Cole Harris, Wade Davis, Hugh Johnston, Patricia Roy, David Stouck, and Graeme Wynn. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. As of September, 2018, Provincial Government Patron: Creative BC

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

Leave a Reply