26 Craftsmen: Truth to Material

Wood derived from the bioregion skirting the Salish Sea is the "truth to material" that connects Mungo Martin to a thriving realm of post-hippie craftsmen and artists.

February 04th, 2019

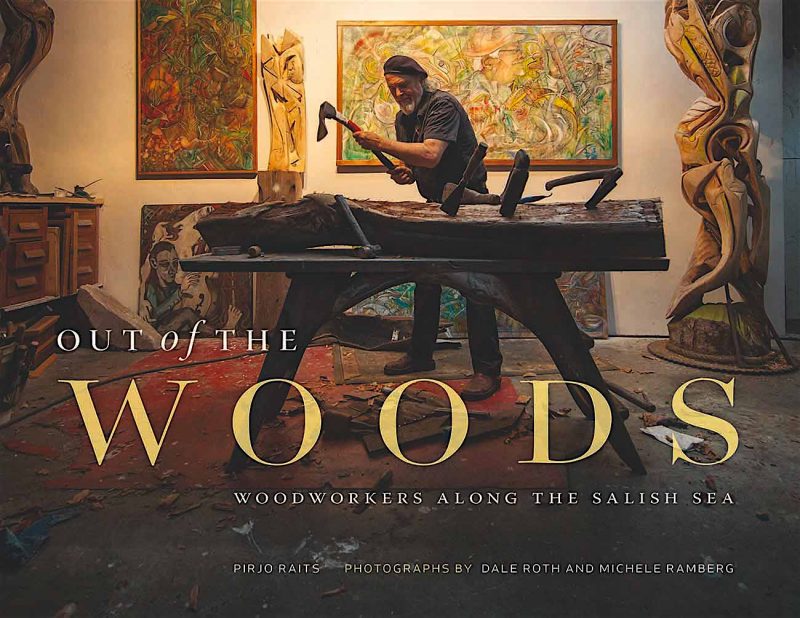

“Out of the Woods is a treat to the eyes and hearts of west coasters,” says reviewer Grahame Ware. This smartly designed and graphically strong digest surveys a group of 26 craftsmen and artists.

Out of the Woods: Woodworkers along the Salish Sea

by Pirjo Raits

Victoria: Heritage House, 2018

$34.95 / 9781772032604

Reviewed by Grahame Ware

*

There are trees … which in their single lives have spanned the entire history of civilized man. We woodworkers have the audacity to shape timber from these noble trees and give it a second life. — George Nakashima, from Soul of a Tree: A Master Woodworker’s Reflections (Kodansha, 2012).

This smartly designed and graphically strong digest surveys a group of 26 craftsmen and artists whose “truth to material” is wood derived from the bioregion skirting the Salish Sea.[1] Their success underlines the popular appeal of wood sourced from the forests and shores of Vancouver Island — the temples where artists worship. Wood sculpture and woodworking have always been popular on Van Isle but never more so than now. Why is that? I believe it is the result of some serious cross-pollination in our culture: Northwest Indigenous and fusion Native art are in flower, and for fifty years at least, hippie-artists have been buzzing around leaving their creative pollen on everything in their west coast gardens. Now you throw in the well-pensioned Boomers cresting on their woodworking skills in their final innings, wanting to bring a west coast soul to their homes and – voilà — it all adds up to tremendous interest in wood as a touchstone in west coast arts and crafts.

With its strong design and photography, Out of the Woods shines a welcome light on wood artisans and artists, despite its often-breezy vignettes. But no worry — this is, after all, a book looking for a coffee or kitchen table, preferably one that is both breathtaking and divine. The appropriate table for this book is a sinuous, rustic slab of hand-planed, west coast wood that would surely make George Nakashima smile.

Phoebe Dunbar: Genesis of the book

A history of Salish Sea carvers and woodworkers is long overdue. So it fell to Phoebe Dunbar, a woodworker from Sooke, to provide the wood shavings to get this fire started. The retired educator and community liaison worker came to woodcarving relatively late in life, in about 2005, and now does exquisite work creating bowls from voluptuous wood burls. Her prime creative catalysts were a love of natural history and wanting to be outside as often as possible with the al fresco experience.

Dunbar felt that her story, intermingled with those of other woodworkers and carvers in the Sooke area, would make a good foundation for a book. From Sooke, she got the project rolling from its forest roots and then steered the creative team from studio to studio, from artisan to artist. The doughty Dunbar told me:

I was very inspired by the years of being on the San Juan Ridge [an inland ridge that runs parallel to Juan de Fuca strait between Jordan River and Port Renfrew], that aligns with the Kludhahk Trail.[2] For approximately 70 kms along this ridge, you pass through stands of old growth and subalpine forests in various states of decay. Small, twisted and disfigured trees had been shaped and “bonsaied” by years of heavy snow. I was more than fascinated… I was inspired. It was there that I learnt so much about trees, seasonal weather, climate change, landscapes, geography, and wood — especially burls, grains, grain patterns, bird’s eye, root balls, and roots.

But Dunbar was not alone in this project. Once the interest of a publisher, Heritage House, was confirmed, the team took shape. First, the camera duo of Dale Roth and Michele Ramberg came on board to do the photography. They made their names in the corporate world of Calgary, though Roth now lives in Vancouver. In business since 1993, this is their first book credit. They shoot with 50-megapixel Hasselblad H3D cameras (the company has honoured them with awards for their work), while letting out the finishing to others.[3]

The original idea was to shoot the whole thing in black and white, but the mist-drenched, dark, often wintry skies caused them to rethink this approach. They told Applied Arts magazine in 2017 that they had to employ lighting stands and shoot in colour to show the depth, look, and colour of the wood.[4]

Next, the retired newspaper editor, Pirjo Raits, was engaged as writer, and finally the talented Lara Minja of Lime Design was wooed by Lara Kordic, the editor at Heritage House. Minja did a lot of good design work all across Canada before she and her partner relocated to Victoria. She has done high-end art gallery catalogues, stamps, and boxed packages of stamps for Canada Post and recently quarterbacked a beautiful book, The Language of Family, (2017) for the Royal BC Museum. Her work for Canada Post’s marvellously-packaged tribute to Canada’s greatest baseball pitcher of all time, Fergie Jenkins, is simply awesome. Minja’s work pulls it all together and this is where the book really shines.

Now they were set — but it still took them the better part of two years to see Out of the Woods to fruition.

Out of the Woods reveals a commonality of carving in wood that unites these artists and reveals the method in their madness: a common pattern of giving it up for love of wood in all its myriad manifestations. The sculptors and carvers of the Salish Sea (or, to oldtimers, the Strait of Georgia and neighbouring Juan De Fuca Strait) embrace an ethos and share a model of how to tread lightly in the woods and then sprinkle their own stardust-sawdust out of the woods. Their carving material comes in many cases from burn piles (from land clearing or logging companies) and from standing dead trees: from bounty salvaged from logged-off sites or beachcombed refugees ripped from the forests, marooned and neglected as driftwood on coastal beaches. Their materials are not generally from industrial sources but from magical happenstance and artisanal tributaries.

A deep spiritual empathy for the forest and the sea binds the woodworkers and artists. They tap into wood’s timeless and ancestral quality, which surely is a primary source of human artistic expression. One has to look only to the oldest piece of recorded sculpture or idol in the world, made over 11,000 years ago — the Shigor idol from Siberia, a seventeen-foot log of Siberian larch. Local authenticity is what the public is now attracted to in west coast woodworking and sculpting. Is this book’s popularity and emergence as a BC Bestseller an indication that we desire an overarching, organic counterbalance to our increasingly digitized and urban lives? A basic realignment in our age of climate change, where protecting Mother Earth has become a transnational concern of primary importance? Sculpture and carving from wood remind us, it seems to me, of something in ourselves that we don’t want to lose.

The Salish Sea woodworkers and carvers featured in Out of the Woods illuminate the spectrum of wood’s beauty and take it far beyond its use as a functional, green, renewable element to bring out its deep, primal, intrinsic beauty. Its living quality comes as a balm to lovers of sculpture intimidated and depressed by the industrial installations and gargantuan forms of postwar steel of David Smith, Anthony Caro, and Jeffrey Rubinoff. Their work does not touch my heart while the work of Aivars Logins, Phoebe Dunbar, and Michael Dennis does.

The wide range of artists and artisans in this book is impressive, but in my opinion, 26 was too many and puts the book’s focus at risk. In keeping with their own stated criteria, I would have saved the cabinetmakers, wood turners, luthiers, etc., for another volume. Winnowing down the group would have allowed more in-depth discussion of the individuals rather than the jotty, interview-overview reporter approach of Raits. And, of course, it would have freed up room for more pictures! But, of course, that is just me. By the same token, I understand that including a full spectrum of artists and artisans gives the publication wider appeal. Much here is new to me, so their idea succeeded in that the scope of the book with its myriad of woodworkers was, indeed, a good and democratic idea. Either way, this book is an absolute pleasure to read and absorb and provides a foundation and standard for future folios.

Coast Salish carvers of the Salish Sea

What we now consider west coast wood sculpture and carved art rests in two lines of origin. The first line is that of Mungo Martin and the Indigenous people. Woodcarving as an art and a craft has been going on in and around the Salish Sea for quite some time. Martin understood that, to be meaningful, his work needed to be seen as art and not marginalized as “crafts,” curios, or trinkets. This was essential in the evolution and the acceptance of carving (not just monumental art or “totem poles”) as art within the western notions and ideas of that activity. The most sacred pieces — rattles, sticks, drums, etc. — were generally not publicly displayed or traded as commodities. Of course, these sacred items were essential ingredients to the potlatch, a ceremony central to the Northwest Coast people that was rendered illegal in 1927.

Martin was old enough to have been spared the de-programming of Kwakiutl beliefs and shamanistic practices by the Potlatch Law and residential schools. As a chief, he taught the craft of carving totems at Thunderbird Park in Victoria. He taught and influenced many, including Godfrey Stephens, Bill Holm (the Seattle art historian who married his daughter), Bill Reid, and Tony Hunt. Martin’s belief in seeing native objects as art was buttressed through the empathy and intellectual understanding of UBC anthropologists, Harry and Audrey Hawthorn, who provided tremendous support.[5]

It has only been since the late 1960s and early 70s that Indigenous carving and collaboration between Native and non-Native artists (fusion art) has found a critical mass. The inclusion of Coast Salish carvers, Charles Elliott, John Marston, and Carey and Victor Newman in Out of the Woods gives it an anthropological ballast, a Northwest Coast cultural gravitas that is most welcome — especially when one realizes that Godfrey Stephens, featured at work on the book’s cover, was an early apprentice of the great carvers and educators Mungo Martin and Tony Hunt.

Nothing exemplifies this fusion or cross-cultural partnership more than the creation of the UBC ceremonial mace in 1958. It was a collaborative affair spearheaded by George Norris from a commission given to Bill Reid. Norris found a five-foot-long trunk of western yew (Taxus brevifolia) and fashioned a thunderbird motif up and down the mace, and Reid — still a CBC broadcaster and not yet a jeweller — applied copper to various eyes and aspects of the carving. He had not yet reclaimed and proclaimed his Haida identity. The mace was first used in the Fall Convocation of 1959.[6]

This was well before Norris would become famous for his crab sculpture at Vancouver’s planetarium-museum on Burrard Inlet (1968), or before Reid would become even more famous for his scintillating installations depicting Haida culture at the Vancouver International Airport and UBC’s Museum of Anthropology. The point here is that the combined efforts of political will (President Larry MacKenzie of UBC), of a white sculptor (Norris), and of a broadcaster-cum-jeweller (Reid) created a symbol of a new authority infused with fresh and collaborative energy. The mace was a cultural amalgam, an artful object and powerful symbol born of cooperation, alliance, and partnership. This kind of dynamic became an acceptable process for native art to step up and stand proudly in the west coast’s cultural spotlight.

Now there was a joining of forces from both sides of the equation. Native art was finally getting its due … but slowly. Tony Hunt, hard on the heels of a successful art show in 1967 at the Vancouver Art gallery curated by Bill Reid and Bill Holm, entitled Art of the Raven, opened a gallery in Victoria of the same name. His bread and butter was, not surprisingly, prints. Goldsmiths and carvers had always been the best printmakers stretching all the way back to Albrecht Dürer and William Hogarth. In fact, I bought a Tony Hunt print in the mid 70s of a Tshimshan long house from his shop; it is still on my wall.

Acceptance in the wider cultural marketplace of Indigenous Northwest Coast art was the key to revitalization. There was a latent cottage industry waiting to unfold at the family and village level. Indigenous artists were unashamedly getting back to their roots. Re-learning cultures and teaching carving exploded like Mt. St. Helens blowing off its Cascadia peak! Yes, it was earthshaking.

But has the production of carved native crafts and art swung too far the other way? Charles Elliott, featured in the book, thinks so. He doesn’t approve of “the overabundance and commercialization of First Nations art” (p. 35). The Coast Salish carver is glad, though, that people are finally understanding his people’s art and that it isn’t inferior to that of the Haida, Tsimshan, or Kwakiutl. His “Balance of Power” is a superb integration of Salish myths, superbly photographed. Like the Musqueam printmaker, Susan Point, Elliott uses traditional fibre spindle designs for his Coast Salish “mandalas” (p. 38).

Charles Elliott, “Balance of Power.” Thunderbird (spiritual) and Orca (physical), with wolf and raven in wings. Yellow cedar and acrylic paint. Photo by Dale Roth and Michele Ramberg

The section on John Marston is a delight. Is anyone doing better work than him right now? The photos in Out of the Woods show the size and scope of his studio and his projects. One of his most recent was “Shore To Shore,” a homage to his great-great grandfather Portuguese Joe, the Azores whaler. His brother Luke — also a carver — helped create this bronze sculpture cast from a yellow cedar carving.[7] The coverage of John Marston in this book is much needed. He is an exacting artist of the often under-represented and appreciated Coast Salish. His skill and the smoothness of his carving and the finish on his work are much better than most who ply the trade.

Another young native carver is the crazily talented Carey Newman, who turned in his opera tonsils for a bent knife. Thank god (or his/her representative) that he did! His metamorphosis occurred when he realized the extent of his father’s pain and suffering at residential school. That is when Carey Newman committed himself to carving. For Newman, the idea of his project, The Witness Blanket (2012) was a natural evolution. He won the commission and Witness Blanket became the artistic cornerstone of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission’s healing mandate; in March 2018, it was awarded the Meritorious Service Medal by the Governor-General (p. 107).[8]

His father, Victor Newman, is also featured in Out of the Woods, but his interesting backstory is lacking. His aunt, Ellen Neel, was the pre-eminent progenitor of native crafts and totem-making in Stanley Park in postwar Vancouver, but Newman had absolutely no grounding or training in carving until late in life due to his incarceration in a residential school. Like Bill Reid, Victor’s talent was lurking in an inert state. But working injuries from logging and fishing left the door open to a five-month course in carving at ‘Ksan, the native arts school in Hazelton, run at that time by Freda Diesing. A Vancouver School of Art grad, Diesing herself was a late bloomer, fortunate to be taught by Tony Hunt, Bill Holm, and Robert Davidson when she was 42.

Once Victor Newman moved to Sooke in 1971, he gained employment teaching carving to students through the Victoria School Board while his wife Edith taught in the public school system. They raised a family and made a life. The uncaptioned full spread picture (pp. 116-7) of what appears to be Victor’s carving tools is one of the best photos in the book. But again, there are so many good pics!

Jan Zach

The second line of influence in west coast woodworking can be traced back to Jan Zach (1914-1986), a Czech artist and teacher who moved from Brazil via New York City to Victoria with his B.C.-born wife, Judith, in 1951. Zach advocated and proselytized for the use of driftwood not only as a “truth to materials” element, but one that was distinct to the larger Pacific Northwest region. His mature students included internationally recognized Victoria sculptors Elza Mayhew (1916-2004) and Winnipeg-born Bob de Castro (1924-1986).

In 1958 Zach moved down the coast to the University of Oregon to develop a very successful sculpture program. He recalled:

I left Brazil in 1951 and went to Canada where I came in contact with the powerful, organic world of the Pacific Northwest. Victoria’s magnificent beaches exerted a strong influence on my sculptural forms. The endless variety of shapes cast up by the sea, roots of trees, branch fragments and seaweed impressed me with the immense vitality inherent in the organic world. They clarified for me certain sculptural concepts of growth and movement through time, as expressed in the twisting and thrusting trunks and roots of trees. I was struck by the tremendous vitality of the totems and masks of the Indians of the Pacific Northwest Coast with their particular rhythm of color patterns and their plastic understanding of carving.[9]

At the time of his departure to Eugene, Zach was working on a Victoria-created wood sculpture piece, “Resistance.” Now housed at the Hallie Ford Museum of Art in Willamette, Oregon, it was carved from battered logs gathered on the Dallas Road beach and assembled in 1955. [10] With modern sculptors seeking and getting inspiration from native carving, it was just a matter of time before the world noticed, and curator Erna Gunther curated Pacific Northwest art alongside Picasso and Modigliani at the Seattle World’s Fair art show in Seattle in 1962.

The Hippie Virtuosos

Several other woodworkers grabbed my attention in this lovely book. Darrel Nygaard owns one of those places that you drive past on the Old Island Highway in Union Bay and then pull over and drive back; it’s just one of those places. Nygaard’s work has a decidedly rustic edge to it that seems so right. His style and sensibilities are perfectly suited to making funky hollowed-out cedar stump containers (p. 124) melded with dwarf dissected Japanese maples (Acer palmatum var. dissectum), dwarf conifers, etc. With a flair for an evocative, woodland garden vibe, Nygaard does some very nice burl bowls and shows a great eye for the artistic incongruities of wood, especially red cedar. His eye and energy have brought together an absolute emporium of west coast beachcombing bric à brac at his studio, Sea-Change Studio-Gallery, which he shares with his partner, Corry Lunn, a ceramic artist who does some lovely sculptural work.[11]

Steve Van Vugt (aka “Sir Drifty”) lives on Hornby island. He is nicely featured here with some to-die-for quotes such as, “The driftwood here is spirit wood.” Driftwood assemblage and collage seem to be his specialty or, at the very least, one of them (“My love for driftwood … that’s why I live here”). Sir Drifty likes to reference them as “land art installations.” The best one shown is “West Coast Teepee Rendition,” made of long, narrow, six-foot lengths of cedar shakes and adorned mystically as one would expect from this knighted tripster and ex-antiques dealer from Germany via White Rock. To really appreciate his oeuvre you’ll have to buy this book.

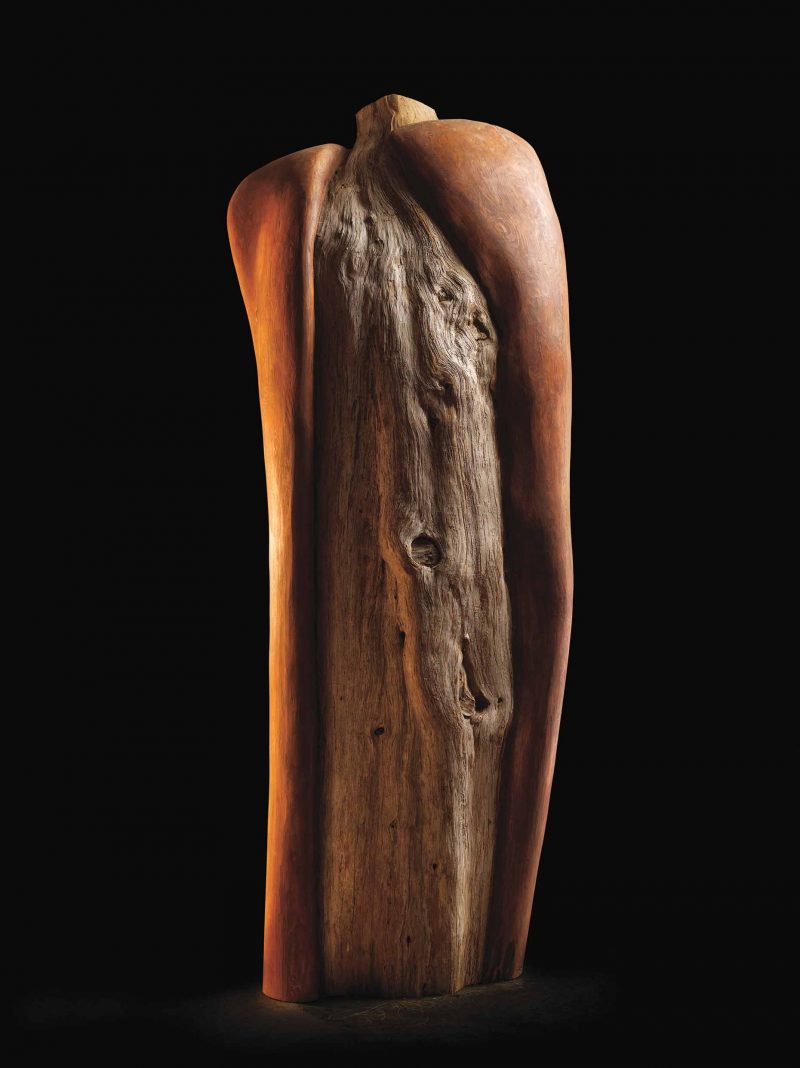

The first time I saw Michael Dennis’s work was ten years ago in Lloyd Kahn’s acclaimed Builders of the Pacific Coast (Shelter Publications, 2008), which featured a small structure based on a Japanese teahouse. It is astonishing just how far Dennis’s wood sculpture has come. He has been most prolific and creative these past two decades with many private and public commissions. His work rarely draws anything but praise and love. Undoubtedly, he has become one of the most sought-after sculptors working in natural wood and wood forms — certainly right up there with the American David Flood and, to a lesser degree, the Brit David Nash (born 1945). One of Dennis’s most endearing projects is the group statuary “The Ancestors,” that he created and donated to the Denman Island Natural Burial Cemetery;[12] another is “Dance of Life,” which stands in front of Denman Island’s Activity Centre.

Vancouverites might know Dennis’s Reclining Figure (1991), perhaps his best-known work, at what is now Dude Chilling Park in the Mt. Pleasant area. One of his first public pieces, this cedar log assemblage was the inspiration for the re-naming of the park in 2012. “The Dude” will be bronzed sometime in the not-too-distant future.[13]

I appreciated the photos in Out of the Woods showing how into-the-process (i.e., messy) Dennis’s studio was. Ditto for Godfrey Stephens. It warms the cockles of an artist’s heart to see the mess of others. It can mean only one thing — they’re creating!

Gurdeep Stephens with her uncle Godfrey Stephens’ sculpture at Swan’s Pub in Victoria

Out of the Woods cover boy Godfrey Stephens is no stranger to anyone who loves wood sculpture. He’s been at it for over forty years and is rightfully the elder statesman of this book. He is also the subject of an award-winning book by his niece, Gurdeep Stephens, Wood Storms/ Wild Canvas: The Art of Godfrey Stephens (Victoria: D & I Enterprises, 2014).[14] Anyone who has visited Swan’s Brewery Pub & Hotel in Victoria and wandered to the back room will find one of the most captivating pieces of wood sculpture ever created. This stunning work was bought by the late Michael Williams and transferred to the University of Victoria (which, incongruously, now owns Swan’s) upon his death. And, as you quaff your craft ale, take a moment or two to commune with this convoluted carving that even Picasso would be excited about.

But not everyone seems to be so enthralled by Stephens’ wood sculpture. Cultural historian Maria Tippett is somewhat prickly about his achievements. In a BC Studies review of Gurdeep Stephens’ book she asks, “But does a Bohemian life style along with the publication of someone’s work in a glossy coffee-table book make him or her an artist? In the end it is the work itself that counts. In this writer’s view the jury is still out on the kind of achievement represented by Godfrey Stephens’ artistic oeuvre.”[15]

The answer to the question as to whether or not a coffee-table book about a Bohemian artist legitimizes an artist as an artist is, of course, “No.” However, Tippett’s rhetorical query about Stephens’ work didn’t need to be posed in the first place. If he never did anything else, Stephens’ Weeping Cedar Woman will stand as a legacy beyond the cerebral musings of any art historian. It was created spontaneously in 1984, within a matter of weeks, with the help and collaboration of Nuu-chah-nulth friends and hippies in Tofino, unburdened by any applications to regional, provincial, or federal arts councils or even a single game of phone tag with an arts manager wonk. Nope. Stephens created this marvel and then let it stand proudly as a focus and catalyst for the peoples’ protest against the industrial-sized stupidity and corporate crassness of MacMillan Bloedel Limited in its plan to clear-cut much of Meares island.

There is a talismanic power and magic to Kle Pil Kanimskit (Weeping Cedar Woman) that few sculptures in B.C. or Canada have ever possessed. It has the power and impact of Brazilian painter’s Candido Portinari’s Geurra e Paz (1952-56). The genesis of Weeping Cedar Woman was a fevered call-to-arms, so unlike the often constipated process of public sculpture commissions to bring “art” to our environment. Stephens related this to Shayne Morrow in 2014:

“It was created in a frenzy,” he [Stephens] said. “Everyone was absolutely panicked. I got in on the frenzy and thought, ‘What can I say?’”

“Joe and I got in his speedboat and zoomed over to Meares and cut it, and Rod Palm dragged it back with his little tug, and we dragged it up on the beach, in desperation, because we only had two weeks to get it together. I had a chainsaw that I had traded a carving for, and within two weeks, that figure existed.”

Thus one carving begat another via a bartered chainsaw that became the sculpture’s main roughing out tool. After a less than exciting post-protest dénouement, Weeping Cedar Woman began to rot at the base. It has now been restored, and since 2014 has stood proudly in Tla-o-qui-aht Tribal Park outside the Tofino Community Hall. Morrow continues: “She (Weeping Cedar Woman) now has 500 pounds of copper sheathing that has been applied to surfaces such as the tear arches, according to the artist. Her spine is now reinforced with Portland cement and she is mounted on plate steel for added strength.”[16]

For Stephens, Dennis, and all the other artists and artisans featured, I hope that Out of the Woods is followed by an in-depth publication that probes and fleshes out the importance and context of wood sculpture and artisanal woodworking of the West Coast. This book shows beautifully the transience and ephemerality of both the art and the artists. Our landscape and resident cultures created both the forests and the artists, both of which are now under duress. Like wood itself, their sculpture can rot or burn. If not treated and finished regularly, much of the material they utilize is just years away from decomposition, not unlike the workers themselves. Out of the Woods shows that Indigenous and hippie art made of wood are now unashamedly embraced on the west coast by nearly everyone. Undoubtedly, the bioregional charm of wood and the array of art — both functional and fine — contributes to their attraction whether inside houses or working spaces.

Out of the Woods is a snapshot, a photo swatch of time that illustrates why we shouldn’t take our earth and seas for granted. We inhabit a coastline, after all, of tree huggers and orca smoochers. Ensuring that we maintain the natural strength and vitality of land and marine ecosystems against the wanton whims of business includes a collective desire to protect our home. We are going local and native as we hurtle forward into 2019. Nothing shows and reflects this better than the people and the art in Out of the Woods. Well done, Phoebe and friends!

Finally, it is worth noting that none of the people featured in the book is a member of Big Art. This is the Peoples’ Art — the art of wood’s warmth and porosity, not cold steel or acrylic; of utility and beauty, not the commodity of an investment banker stored in a third party warehouse for future wealth appreciation; an art of uncomplicated honesty that you want to live with. These wondrous refugees salvaged from ravaged forests and the turbulent sea, and retrieved through the magical serendipity of tides and storms, live with us like friends or pets.

*

Endnotes:

[1] “Truth to materials” is the artistic and architectural principle that “the form of a work of art should be inseparably related to the material in which it is made.” See Oxford Reference, “Truth to materials,” http://www.oxfordreference.com/view/10.1093/oi/authority.20110803105953905

[2] For the Kludahk Trail see http://kludahk.com/kludahkclub/the-trail/

[3] See http://www.photoed.ca/single-post/2017/08/12/ROTH-AND-RAMBERG WOODWORKERS-ALONG-THE-SALISH-SEA

[4] Applied Arts mag https://www.appliedartsmag.com/features_details.php?id=21§ion=1002

[5] Audrey Hawthorn, curator of the nascent anthropology department when the “museum” was merely a basement in a building at UBC, buttonholed Pierre Trudeau at Expo ’67 where the native art was housed in the “crafts” section and told him of the importance of seeing it as art. A museum with proper display space was necessary, she argued. Trudeau agreed, and eventually Ottawa supplied the funding for the Museum of Anthropology, with its centerpiece, Raven and the First Men, a collaborative piece based on Bill Reid’s small limewood piece. For more info on the making of Raven and the First Men see: http://moa.ubc.ca/wp-content/uploads/2014/08/Sourcebooks-Raven_and_the_First_Men.pdf

[6] For details see Bill Reid: The Making of an Indian (Toronto: Random House, 2003).

[7] For the making of this sculpture, see Susan Fournier, The Art of TS’UTS’UMUTL, Luke Marston: Shore to Shore (Madeira Park: Harbour Publishing, 2014). Fournier wears her scholarship lightly yet rigorously.

[8] For the genesis of The Witness Blanket, see http://muskratmagazine.com/the-witness-blanket-the-most-tangible-reminder-of-residential-schools/

[9] Jan Zach, “Imagery, Light and Motion in my Sculptures,” Leonardo 3: 3 (July 1970), pp. 286-7.

[10] See https://willametteart.pastperfectonline.com/webobject/ABE3B221-B6C7-4A9C-B195-923672083495

[11] Nygaard and Lunn have a Facebook page: https://www.facebook.com/lunnNYGAARDatUB/?rf=873403999514228; 7A) a great YouTube video on Darrel’s burl bowls: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Vl-LI1EztOU&feature=share

[12] http://dinbc.ca/the-ancestors

[13] See Vancouver Courier, October 2, 2017.

[14] Wood Storms/ Wild Canvas won an Independent Publishers gold medal award for non-fiction in 2015: https://thedeepersideblog.com/2015/06/25/wood-storms-wild-canvas-wins-gold/

[15] Or was Tippett perhaps just limited by the space repression of this hard copy journal? See http://bcstudies.com/?q=book-reviews/wood-stormswild-canvas-art-godfrey-stephens

[16] Shayne Morrow (April 28, 2014) in the Nuu-chah-nulth newspaper, Ha-Shilth-Sa: https://hashilthsa.com/

*

Grahame Ware is a writer and carver on Gabriola Island. He studied creative writing and communication studies at Simon Fraser University. As a feature writer, often under the Buzz Ware handle, he has been published in Georgia Straight, Vancouver Magazine, TV Week, TV Guide, and Toronto Star, and he had shows on CBC radio, CKVU-TV, and CO-OP radio as a freelance broadcaster and producer. He worked with Ken Smedley in performing plays by George Ryga, Sam Sheperd, and George F. Walker in the Okanagan. He taught ornamental horticulture at Okanagan College, made a living as a landscape contractor and rare plant nurseryman, and spent three years as editor of the Alpine Garden Club of B.C. With Dan Helms, he is author of Heucheras and Heucherellas: Coral Bells and Foamy Bells (Timber Press, 2005). He has contributed articles to the International Rock Gardener, The Rock Garden, The Plantsman, and The Ormsby Review. For nearly a decade he has dedicated himself to creating gongshi sculpture with cured driftwood and dried wood as his medium. See www.phantasma.ca for his wood sculpture and related subjects.

*

The Ormsby Review. More Books. More Reviews. More Often.

Editor/Designer/Writer: Richard Mackie

Publisher/Writer: Alan Twigg

The Ormsby Review is a journal service for serious coverage of B.C. books and authors, hosted by Simon Fraser University. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Robin Fisher, Cole Harris, Wade Davis, Hugh Johnston, Patricia Roy, David Stouck, and Graeme Wynn. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. As of September, 2018, Provincial Government Patron: Creative BC

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

Leave a Reply