#478 Burquitlam gangland capers

February 04th, 2019

Property Values

by Charles Demers

Vancouver: Arsenal Pulp Press, 2018

$17.95 / 9781551527277

Reviewed by John Douglas Belshaw

*

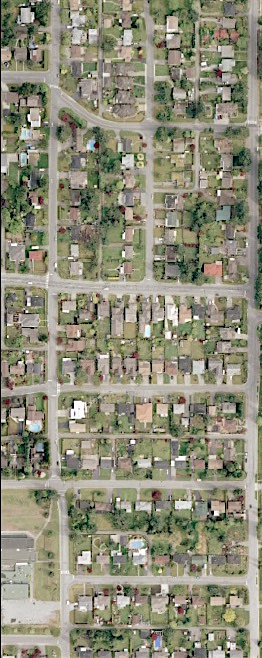

We need to talk about … Burquitlam.

We need to talk about … Burquitlam.

It’s liminal. Which is a scholarly word meaning it occupies “a position at, or on both sides of, a boundary or threshold.” (Thank you, Google.) It’s a fragment of two suburban realms in Greater Vancouver. Much like Rocky and Bullwinkle’s Moosylvania astride the Canadian-American border in Lake of the Woods, it is insufficiently appealing for either side to claim it fully.

“Burquitlam” is a portmanteau, a word made up of parts of two other words. It is unique in the Lower Mainland and possibly in all of B.C. No, “PoCo” is not a portmanteau: it is a lazy compression. Likewise, “New West” is just shortness of breath and lack of effort. “Ioco” isn’t a portmanteau either; it’s the initials of the Imperial Oil Company. Most disturbing of all, “Port Mann” is not a portmanteau, although it ought to be and if I had a tugboat operation or a tow truck company I know exactly what I’d do.

For nearly eight years Burquitlam had its own provincial constituency and its own MLA. This may be taken as proof that someone at Elections BC enjoys a joke. There was only ever one MLA from Burquitlam: the perfectly named Harry Bloy. Bloy has the distinction of being the sole Liberal MLA to support Christie Clark’s leadership bid in 2011. He subsequently fell on his own sword over a leaked email, as if being “the Honourable Member for Burquitlam” wasn’t enough to answer for.

Burquitlam’s first big cultural moment came in 1982 with the release of the film, Big Meat Eater. It’s a cult musical involving dismemberment and if you haven’t seen it, nothing will make you more glad to be alive. Late in 2016 Burquitlam got its own SkyTrain station on the Evergreen Line. Expect the voice of Rod Serling to alert you, “You are entering another dimension: a dimension of sound, a dimension of sight, a dimension of mind. You’re moving into a land of both shadow and substance, of things and ideas. You’ve just crossed over into … Burquitlam’.”

Thanks to East Vancouver writer, comedian, and playwright Charles Demers, Burquitlam at last finds a home in literature. The premise of the novel is the extortionate price of housing in Greater Vancouver. This isn’t a whine-fest; most of us can remember affordability but what about younger people who have only ever known runaway housing prices?

Well, everyone complains about the weather and what it costs to buy a home, but at least Demers’ bromantic characters do something about it. Trapped in a state of prolonged and enforced dependency and immaturity, they set in motion a plan to ensure that at least one of their number can hold on to what little he’s got. Sadly, this draws the attention of money-laundering gangsters who Just. Don’t. Care.

Like all good satires there is little about this story that can be disclosed without spoiling the whole. The writing is sharp, the humour is dark and strangely plausible, and the violence is intimate and imminent. The description of one especially terrifying thug captures these qualities nicely: “Ferreira was the kind of man who it was impossible to fathom had once gestated inside of another person, as though a quail’s egg could hatch a mastiff. He moved through life with the confidence of a man who could never be strangled, since no one pair of hands could ever wrap themselves around that neck” (p. 144). I gasped as often as I laughed.

Demers doesn’t just write the city, he reads it. His characters are set in a 10,000-year old space and they continually rub up against historic forces they cannot always apprehend. Neighbourhoods in this novel are made of people and interactions, not multiple listing signs and condo presales. His potted account of Fraser Mills and Maillardville is the neatest I’ve seen. And there’s no local heritage sentimentality. Expo ’86, for example, is cut down to size as a “third-tier transportation themed World’s Fair.”

When Demers shows us the Vancouver waterfront, where “two different right-wing provincial governments had each built massive convention centres, separated by about twenty-five years and maybe six hundred feet,” that’s as sharp an insight into the character of BC politics as you’ll find in a novel (p. 129). In one paragraph on one page (p. 109) Demers describes how local journalism has changed since the millennium and why, in practical terms, we’re all poorer for it.

I know Burquitlam. Or at least I did. I wasted much of my wasted youth there. The only cultural resources were a mall and a shopping plaza (which had, incidentally, an outstanding pizza takeaway long before Little Caesar was even a glint in Big Caesar’s eye). It was all very blue-collar and just lousy with SFU undergrads.

I had my first haircut in at the Cariboo Hotel, got my first job at the Mall (happily, it didn’t last), pranked friends, dated, hung out, and tried to imagine a future beyond the invisible but real boundaries of suburbia. Like Demers’ lads in the “Non-Aligned Movement,” I was a charter member of a mostly harmless and nerdly gang, “The Midnight Autowreckers.”

Demers’ characters are from a different generation, but this book confirms and celebrates continuities in the face of disruption. I imagine that his characters and I have the same eastern-suburbs accent, and that’s a treat.

Any Vancouverite over the age of 35 would benefit from reading Property Values because it reveals ways in which the metropolis’s culture is changing. We may think of ourselves as insulated from some of these transformations, but that’s an illusion. Demers’ manboys are part of a large generation raised on the expectation that they will suffer financially and in terms of quality of urban life while older cohorts toast another year of inflated assessments. If you think they’re not going to have an impact, well, think again. Unlike property, these folks have real values.

*

John Douglas Belshaw, Ph.D., FRHistS, is a history professor at Thompson Rivers University — Open Learning. Among other accomplishments, he is the co-author, with his colleague and spouse Diane Purvey, of Vancouver Noir: 1930-1960 (Anvil, 2011) and the editor of Vancouver Confidential (Anvil, 2014). Belshaw makes his home in Vancouver’s East End where he does academic stuff and dabbles in fiction.

*

The Ormsby Review. More Books. More Reviews. More Often.

Editor/Designer/Writer: Richard Mackie

Publisher/Writer: Alan Twigg

The Ormsby Review is a journal service for serious coverage of B.C. books and authors, hosted by Simon Fraser University. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Robin Fisher, Cole Harris, Wade Davis, Hugh Johnston, Patricia Roy, David Stouck, and Graeme Wynn. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. As of September, 2018, Provincial Government Patron: Creative BC

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

Leave a Reply