#371 Burning down the house

September 11th, 2018

Tom Burrows

Vancouver: Figure 1 Publishing, 2018.

by Scott Watson and Ian Wallace

$50 / 9781927958889

Reviewed by Robert Amos

Co-published with the Morris and Helen Belkin Art Gallery

*

Born in Ontario in 1940, Tom Burrows moved to Vancouver in 1960 hoping to study medicine, but instead earned a B.A. in art history at UBC in 1967. For one memorable period he resided, Malcolm Lowry-like, among the free spirits who had set up camp on the Maplewood Mudflats, a tidal plain that skirts Burrard Inlet. east of the Ironworkers Memorial Bridge, until the local government burned down the squatters’ ramshackle huts and cabins in 1971.

Burrows furthered his studies at Saint Martin’s School of Art in London, England. Here, reviewer Robert Amos, after noting the artistic and intellectual influences on Burrows — including dada, performance, installation, minimalism, formalism, found objects, titular mnemonics, and photo + text — identifies what he calls the artist’s “junkyard minimalism” and relishes Burrows’ interest in the stories of his own life. “And with that, the artist began to tell those stories, and in that revealed himself.” — Ed

*

In forty years of writing book reviews, I have learned that you should never offer a “mixed review.” Say you like it or you don’t. Trying to do both is just confusing. But, in the case of this Tom Burrows book, I’ll make an exception.

In forty years of writing book reviews, I have learned that you should never offer a “mixed review.” Say you like it or you don’t. Trying to do both is just confusing. But, in the case of this Tom Burrows book, I’ll make an exception.

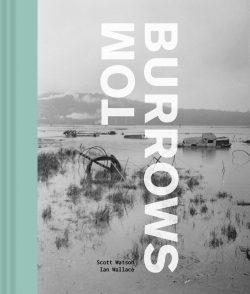

Let’s begin with what I don’t like about it. The book itself has heavy cardboard covers and is printed on a matte paper that doesn’t show the photos well. Many of the images are from “archival” originals that weren’t high quality in the first place, and Burrows’ later art work is, as Scott Watson admitted, impossible to reproduce adequately. The cover, in silvery shades of grey, is neither attractive nor informative.

The book should have accompanied the retrospective exhibition about Tom Burrows, which was held at the Belkin Art Gallery at UBC from January to April, 2015. Is there a compelling reason that it took three and a half years for it to reach the bookstores?

Still, I was interested to learn about Burrows, who has been part of the Vancouver scene since the early 1960s. Scott Watson has done a lot to bring that generation to our attention, and the name “Tom Burrows” rang a bell for me: he was the artist who put steel hoops on the Maplewood tide flats in North Vancouver and watched their changing reflections as the water came and went.

I began reading the essay written by Scott Watson, director of the Belkin Gallery. By the second page Watson had directed me to Kant’s Critique of Judgement, and then reported that he found “useful the terms parergon and frame to describe the formal aspects of Burrow’s work.” What is a parergon? By the fourth page, he had included references to Jacques Derrida, Meyer Shapiro, and Clement Greenberg. I was about ready to stop right there, but I persisted and found that Watson made a workmanlike job of describing Burrows’ varied and occasionally successful career as a sculptor, through dada, performance, installation, minimalism, formalism, found objects, photo + text and much more.

As I read along, I remembered that I had met Burrows. Jerry Pethick, one of the great sculptors of my generation, with his wife Margaret and son Yana had left San Francisco’s School of Holography for Hornby Island, where they camped on a rocky ledge on the foreshore of Downes Point. In the winter of 1978, Jerry suggested I might like to camp there the following summer, at which time he introduced me to the neighbours at the Point: Anne and Wayne Ngan, Doris and Jack Shadbolt, Gordon Payne, and Tom Burrows.

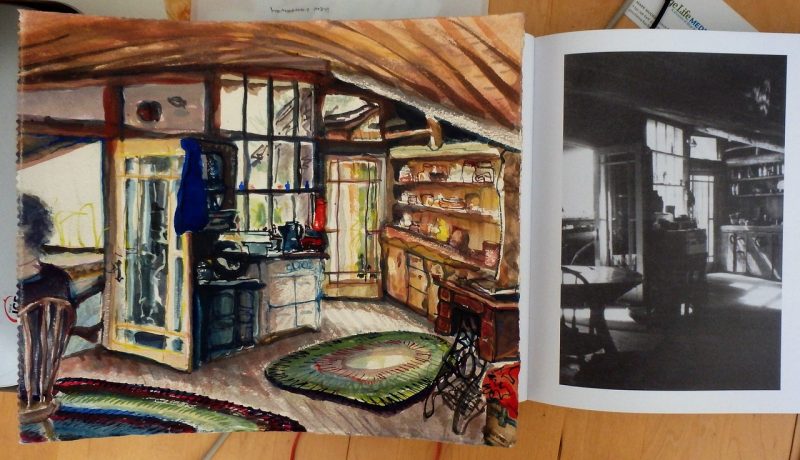

Burrows had built an amazing home there, carved into the cliff face over the water’s edge. Its structure is a beautiful array of logs. Described as a “sod cover on hyperbolic roof of wood, peeled poles and beach logs,” this masterpiece of the wood-butcher’s art was designed by Bo Helliwell and built by Burrows. That summer, I sat in his kitchen and painted a picture while Jerry and Tom talked.

Inspired by this personal connection, I returned to the book with more interest. After his time squatting in a shack on the mudflats in the 1960s, Burrows studied sculpture at Saint Martin’s School of Art in London. Working with “found objects,” he assembled work that led him to a sort of junkyard minimalism. Back in Canada, he exhibited occasionally, supporting himself by work on construction sites. Then he discovered poured acrylic.

Burrows’ Maplewood house set on fire by the District of North Vancouver, December 1971. Photo by Jerry Williams.

By the 1990s, his signature technique was fully in place. “He pours, and also sometimes brushes, scatters, draws and lays down the liquid polymer…”, Watson explained. The resulting objects are acrylic panels one inch thick. “Because the surfaces are not opaque, but have translucent depth … they are impossible to faithfully reproduce as images.” (p. 76). Not a good sign.

I read further, hoping Ian Wallace, another essayist, would help me out. “Various pigments and materials are dropped blindly onto the backs of the panels during fabrication, allowed to mix at random so that a variety of aesthetic effects erupt from the resulting tropic reactions,” Wallace explained. (p. 180). Blindly? At random? Tropic reactions? What am I to make of that?

Perhaps Burrows’ original plastic pieces exert a subtle mystique, but looking through full-page full colour reproductions of his later work is about as inspiring as studying paint chips at Home Hardware. I wasn’t planning to reserve shelf space in my library for this book, but before giving up I dipped into the “selected writings” by Burrows, which were chosen to accompany the illustrations.

“It is coincidental if my material/processes produce the illusion of representation,” the artist warned us. No intended illusion, no representation. “A title /story is attached to the panel only after its material completion … as a memory device (a mnemonic), rather than the panel serving to illustrate a narrative.” No narrative, and the titles are meaningless.

And then, suddenly, something that Burrows said overshadowed all that critique and theory. For, in the midst of the talk of formalism and minimalism and tropic reactions, in the midst of the impossible and the blind and the random, the artist made a startling revelation. In parentheses at the bottom of page 122, Burrows admitted this: “(P.S. I do like my stories.”)

And with that, the artist began to tell those stories, and in that revealed himself. On the next page he launched into a story about his father’s bad habits. “Every day: three packs of Buckinghams (a strong filterless cigarette), a quart of brandy and an every-increasing dose of pharmaceutical barbiturates, the effects of which he was increasingly immune to” (p. 123). And, as he reported, his father died of an overdose of milk!

Now he had my attention! At this point my engagement with the book entirely changed and I read with full attention to the end of what Burrows had to say. It turns out he is an interesting person who has had an interesting life. Those soft-focus reproductions of the art works, which are impossible to reproduce, were somewhat beside the point.

In retrospect, I am grateful for the effort put in by Watson and Wallace to place Burrows in the historical context of B.C. artists. And eventually I enjoyed the artist’s thoughts and stories. Burrows is a child of his time and an estimable sculptor, I’m sure, but I don’t think this book will make it to a second edition.

*

Robert Amos has become known as “the man who paints Victoria,” and his paintings have entered the permanent collections of the City of Victoria, the University of Victoria, and the Art Gallery of Greater Victoria. Amos was the art writer for the Victoria Times Colonist newspaper for 32 years and during that time interviewed many of Victoria’s finest artists. Nine books of his paintings and writings about Victoria have been published by Orca Books and TouchWood Editions. In 2010 his book, Inside Chinatown, (TouchWood, with Kileasa Wong) received the Award for Outstanding Achievement from Heritage B.C., and most recently he released the best-selling E. J. Hughes Paints Vancouver Island (TouchWood Editions, 2018). Amos was made an Honorary Citizen of the City of Victoria (1985) and was elected to membership in the Royal Canadian Academy of the Arts (1996).

*

The Ormsby Review. More Books. More Reviews. More Often.

Editor/Designer/Writer: Richard Mackie

Publisher/Writer: Alan Twigg

The Ormsby Review is a journal service for serious coverage of B.C. books and authors, hosted by Simon Fraser University. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Robin Fisher, Cole Harris, Wade Davis, Hugh Johnston, Patricia Roy, David Stouck, and Graeme Wynn. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. As of September, 2018, Provincial Government Patron: Creative BC

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

Burrows’ kitchen on Hornby Island, painted by Robert Amos in 1978 (left), and photo from book (right). Amos photo

Leave a Reply