Norman Bethune and women

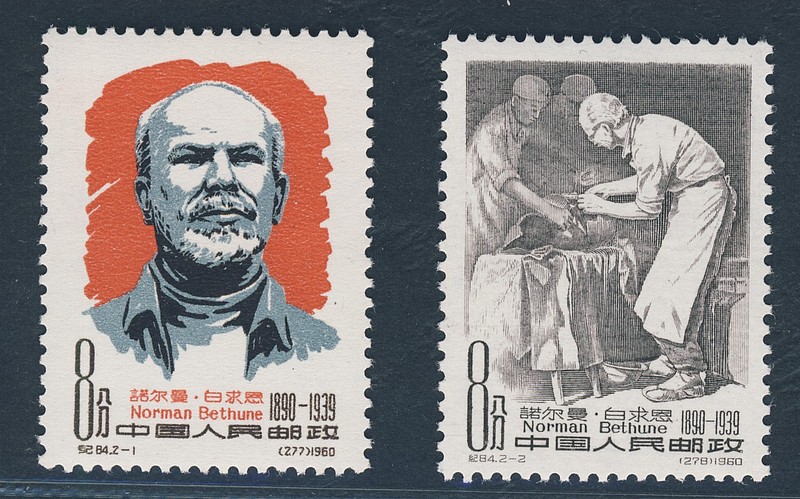

Norman Bethune, the Communist medical pioneer, remains the most famous Canadian in China.

February 28th, 2018

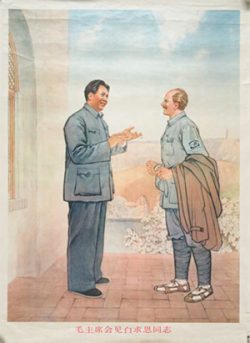

The centre image is the only known photograph of Norman Bethune with Mao Zedong.

In the forthcoming Rediscovering Norman Bethune, Larry Hannant maintains Bethune was not a crass womanizer, as alleged by unreliable biographer Ted Allen. Hannant’s essay is previewed here.

The newest book about Bethune will be launched on March 23 at Vancouver Community College at 7 pm.

It is a little known fact that Norman Bethune is related to the Mayor of Vancouver–Gregor Angus Bethune Robertson.

Norman Bethune, Rediscovering Norman Bethune (Pandora Press $21.95) arose from the “Bethune Legacy and Our Times Forum” that was held in Beijing in September 9-16, 2015, orchestrated by the China Cultural Heritage Foundation, the China Publishing Group, the China Bethune Spirit Research Association, and the “Bethune in China” Project Committee. The organizational efforts of Yan Li, Director of the Confucius Institute at Renison University College, were integral. The book also contains two articles by David Lethbridge of Salmon Arm. 978-1-926599-60-1

Contributor Larry Hannant of UVic previously provided the first comprehensive collection of the writings and artwork of Norman Bethune, The Politics of Passion: Norman Bethune’s Writing and Art, which won the Robert S. Kenny Prize in Left/Labour Studies in 1999.

*

I’M NOT YOUR MAN: BETHUNE AND WOMEN

An essay by Larry Hannant

Doctor, medical innovator, propagandist, artist, political activist — Norman Bethune is nothing if not multitalented. The same complexity marks his character. The accounts of friends and acquaintances portray a man whose personality was multifaceted and contradictory, at once brash, reckless and rude but also tender, compassionate and humane.

No less clouded by contradiction are his relationships with and attitudes towards women. Predatory, patronizing, unfaithful; compassionate, devoted, respectful — all apparently apply to the same man, husband and lover. To tease apart this Gordian knot would require a new biography weaving together his life and those of at least a dozen women. This essay is but preface to that necessary work.

No less clouded by contradiction are his relationships with and attitudes towards women. Predatory, patronizing, unfaithful; compassionate, devoted, respectful — all apparently apply to the same man, husband and lover. To tease apart this Gordian knot would require a new biography weaving together his life and those of at least a dozen women. This essay is but preface to that necessary work.

Regrettably, Ted Allan, one of the most influential commentators on the ways Bethune interacted with women is also one of the least reliable. After his first foray into biography in 1952 with The Scalpel, The Sword: The Story of Dr. Norman Bethune (co-written by Sydney Gordon), Allan’s tales about Bethune became less and less reliable, until with the posthumous online publication of his supposed diaries, the stories have become utterly misleading.[1]

The account invented by Allan that has perhaps been most widely disseminated came in the feature film Bethune: The Making of a Hero (1990), which followed a script written by Allan.[2] In the film, three key scenes label Bethune as a womanizer who cheats on his wife, Frances, and zealously pursues women without regard to circumstances or their wishes.

Ten minutes into the film we see Bethune in 1925, married to Frances. (At the time, they were in Detroit, not Montreal, as the film attests, but that’s one of the film’s less significant inaccuracies.) Clad in his white medical coat, the doctor emerges from an inner room in his hospital office. He emphatically zips up his fly. A comely nurse follows him, adjusting her cap and seeking to elicit some sign of affection from him. Bethune’s reply is brusque, dismissive. The bon vivant doctor is also a hardened sexual predator, we’re advised.

Bethune’s years in Montreal from 1928 to 1936 saw him interacting on many levels with other medical professionals, as well as health and political activists, male and female. After 1930, in the midst of the most profound world economic crisis in history, he was one of many who freed themselves of illusions that capitalism could provide anything but perpetual crisis; they turned instead to socialism or communism. In the Montreal Group for the Security of the People’s Health, Bethune and others collaborated to try to change a medical system that put profit above human needs.

One of the first and most active members of the group was Libbie Park, a nurse, writer and left-wing activist who worked with Bethune for about a year, before he left for Spain in October 1936. Park got to know Bethune well, as outside of their activism they saw one another socially (although never in an intimate relationship). In a later reminiscence about her friend, Park said simply “I liked his attitude towards women.”[3] She describes a man who was remarkably like the most liberated of men today.

“A woman was a person” to Bethune, Park continued, and he acted towards them as he did anyone. He was notoriously dismissive of hypocrisy and “enjoyed exposing smugness of any kind” — whether male or female.[4] Another acquaintance, for instance, pointed out how shocked he was when, after asking the wife of a prominent doctor if she was happy with her life, she replied “Well, yes. But I wish George could make a little more money.”[5]

Park acknowledged that women with whom Bethune had intimate relationships (and he had several in the mid-1930s, after his second divorce from Frances) held quite varied memories of their affairs:

To one, it was an experience she wanted, one for which she shared the responsibility, without regrets. To another the experience simply demonstrated what she thinks of now as Norman’s mindless pursuit of all women.[6]

That said, Park insisted that the label womanizer that is so often attached to him “vulgarizes Norman Bethune’s attitude towards women and in no way captures the kinds of relationships that existed between him and women who were often friends, and sometimes lovers.” That women were “often friends, and sometimes lovers” speaks profoundly to the nature of Bethune’s interactions in what were his most sexually and socially active years. It should be added that there is no suggestion — neither in any reminiscence of anyone who knew Bethune or by biographers who are bound by facts — that he had sexual relations with any nurse.

If we’re to believe both Bethune: The Making of a Hero and official accounts from the Spanish government, Bethune’s womanizing persisted in Spain and led to trouble. In the film, Ted Allan seized the opportunity to paint himself into the picture as Chester Rice, a journalist who joins the innovative blood transfusion institute that Bethune conceived of and did so much to create. “He had been a hero to me,” intones Rice, “but I became disillusioned with his womanizing and his heavy drinking.”

Later in the film, Rice’s allegation is reiterated by the Spanish doctor in charge of the blood transfusion institute, who accuses Bethune of creating dissension within the united front, promiscuous behaviour, exposing his medical unit to unnecessary danger and disrespect for Spanish traditions and customs. The only evidence in the film for any of these complaints, aside from his drinking, is a quick earlier glimpse of Bethune sizing up a blonde Swedish journalist. The two are then pictured, locked in a passionate embrace.

Curiously, this conspiratorial gibberish is also the heart of Spanish authorities’ case against Bethune, which resulted in him being run out of Spain in May 1937. One of the fortunate by-products of the dismantling of the Soviet Union was the release of documents from the Spanish Civil War held by the Communist International. Among them are two that lay out the case against Bethune.

Reports of April 3 and August 17, 1937, both likely originating from the Spanish Communist Party, had a key role in the policing apparatus of the Republican government. Most of the claims they make against Bethune are so specious that they don’t bear repeating. As Michael Petrou, author of Renegades: Canadians in the Spanish Civil War, points out, the “most damning accusation” really springs from Bethune’s two-month relationship with Kajsa von Rothman.[7]

Von Rothman was almost legendary in Spain. Descriptions and surviving photos of the Swede depict a dazzling woman. Kate Mangan, a Briton who worked with her in the Republican Press and Censorship Bureau in Valencia, pictured her as “a handsome giantess with red-gold flowing hair” whose confidence, affability and fluency in seven languages made her popular among the host of foreigners in Madrid and Valencia.[8]

The official Spanish government reports make several allegations about von Rothman, most of them as dubious as those against Bethune. But particularly revealing are the persistent insinuations that she was immoral. She is said to have “lived comfortably” in Barcelona before the war — suggesting that she was a prostitute. She had been dismissed by the Scottish Field Hospital for “immoralities” before she had come to the blood transfusion unit, about December 1936, a canard that historians have dismantled.[9] Contrary to the defamatory reports, von Rothman’s dedication to the Republican cause, for the duration of the war and after, was praised at the time and subsequently.[10]

Republican authorities’ prurient conjecture about von Rothman’s supposed sexual history, and, by extension, Bethune’s morality, speaks to an intriguing but curiously neglected issue in the Spanish Civil War and the writing about it. In that brief moment, Spain was a sexual playground for foreigners, one of the premier opportunities for international lovemaking in the twentieth century. When it became clear that the Spanish people’s heroic resistance would deny General Francisco Franco and fascism an easy victory, progressives, iconoclasts, and adventurers worldwide took heart and threw their hopes, their energies and, for many, their bodies into the struggle.

While much has been written about the 40,000 men and women who made their way to Spain and became part of the International Brigades and its associated medical and other auxiliary services, much less has been written about the more than 1,000 journalists and the countless other witnesses, apostles, spies and adventurers who descended on Spain during the war years.

The motives of those pilgrims ranged from the highest principles to rank opportunism. Indeed, Mangan, who met many of them at the Republican Press and Censorship Bureau, recalled that through the summer of 1937 “we were so inundated with visitors that Valencia might have been a tourist resort. A lot of them were important people but some came for frivolous reasons because it was the fashion.”[11] Whatever their reason for being in Spain, the combination of their youth, their independence of any supervisory power or organization, and the danger they faced created conditions in which coupling was easy, desirable, inevitable and often a balm for the carnage they witnessed.

Some liaisons became famous, among them the affair between photojournalists Gerda Taro and Robert Capa, whose intense professional and personal bond was severed by her tragic death at the front. Others were notorious: the married Ernest Hemingway, who used the opportunity of reporting on the war to woo a new spouse in Martha Gellhorn; women who made their way to Spain to locate men they loved, for example like Kate Mangan, in search of Jan Kurzke, who had volunteered for military service then, wounded, had disappeared;[12] men who embarked on the trek to find male lovers, such as Tom Worsley and Stephen Spender who tried to track down their common lover, the former Coldstream Guard and male prostitute Tony Hyndman;[13] and women and men like Jean Watts and David Crook, who “succumbed to the fatalistic romanticism of wartime” and lived for two weeks almost exclusively in one another’s arms before duty pried them apart.[14]

The fact that these free lovers were foreigners was not lost on some of the zealots in the Republican government. Indeed, it helped to create an undercurrent of moral panic in the country, which was already troubled by contentious issues such as the extent to which Spanish women were throwing off the traditional burdens of their semi-feudal society and taking up hitherto-unimagined tasks, including, for a time, as front-line milicianas.[15]

That moral panic was an unacknowledged factor in the campaign to oust Bethune. He had made an international name for himself through the ground-breaking blood transfusion project. To assert Spanish control of it without causing a rift with the Canadian Committee to Aid Spanish Democracy required not just a rational but also an emotionally-compelling case. The canards about him disappearing with jewelry or visiting the front without justification could be definitively refuted. But “immorality” carried a righteous weight that was harder to dismiss.

What Spanish authorities condemned in Bethune’s brief affair with von Rothman was commonplace among the internationals. Yet it became a stout club used to drive him from Spain, with Bethune so humbled that he conceded that, “I have blotted my copy book.” A scarlet blot it was.

When it turns to China, Bethune: The Making of a Hero’s construction of Bethune as a sexual transgressor continues. There his alleged prey is the fictional Mrs. Janet Dowd, an Anglican missionary. On their second encounter, after he had earlier cursed her for refusing to cast off her neutrality and provide desperately needed medical supplies to the Eighth Route Army, they find themselves in a hotel in rural China. He offers her a glass of wine at dinner, and as they proceed to their rooms later, he unexpectedly imposes a passionate kiss on her. Her response — a firm no — sends him to his room to contemplate her wistfully from his window.

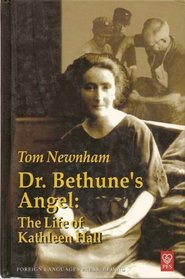

Mrs. Dowd is modelled on Kathleen Hall, a medical missionary from New Zealand who had begun her work in China in 1923 and who in 1938 operated a cottage hospital in Songjiazhuang, a small village in the no-man’s land between the Japanese-occupied north Chinese coastal plain and the mountain districts controlled by the Eighth Route Army.

Surviving in this delicate environment at a time when Japan was not yet at war with Western countries and still tolerated Christian mission work, she met Bethune. From Bethune: The Making of a Hero, we’re told that he pressured her to use her special status to help him obtain supplies, then condemned her as a hypocrite for refusing.

What factual evidence we have challenges this story. The one biography of Hall we have, Tom Newnham’s Dr. Bethune’s Angel: The Life of Kathleen Hall, unfortunately takes a long passage from a dubious source and, by enclosing it in quotation marks, suggests that it’s a faithful reproduction of their conversation. Newnham’s source is Allan and Gordon’s The Scalpel, The Sword, which is based on a 1948 Chinese novel by Zhou Erfu, The Story of Doctor Norman Bethune. And the novel itself, Zhou told Kathleen Hall’s biographer in 1989, acquired all its detailed day-to-day information from Bethune’s interpreter, Dong Yueqian.[16]

Whatever actual words passed between Bethune and Hall, the missionary nurse did not need a dose of invective to understand the dire circumstances and act accordingly. She not only organised mule trains of medical supplies and saw them through Japanese check points, but also attended to wounded soldiers and partisans and recruited nurses for the partisan army, bringing them through rough terrain to the mountains.[17]

For all of this, Hall paid dearly. And we have direct words from Bethune to confirm his reaction. In his August 1, 1939, monthly report on the operation of his mobile surgical team, Bethune wrote:

The medical supplies obtained in the past 3 months have chiefly been the result of the energy of Miss K. Hall of the Anglican Church Mission at Sung Chia Chuang [Songjiazhuang]. … As a result of her activities, her Mission has been burnt by the Japanese. I have always felt and expressed some months ago that too much should not have been asked of these sympathetic missionaries … Miss Hall cannot be used again. Her life is already in danger owing to her help to the Region.[18]

Bethune and Hall never met again, as the Japanese expelled her from the region of China they controlled. Hall’s impression of Bethune remained high. The Canadian missionary Dr. Robert McClure, who disliked Bethune based on a single encounter of about one hour during Bethune’s harried month-long passage across central China, wrote in 1939 that:

Contrary to what I have heard from a lot of other people, Miss Hall thinks rather well of Dr. Bethune and evidently once he gets away from his alcoholic beverages he does a good job of work and is not a bit afraid of hardship.[19]

Hall’s recollections of Bethune, written years later, hinged on her concern that “he might have thought I had let him down when I did not return” to the front-line region she was expelled from.[20]

Hall’s recollections of Bethune, written years later, hinged on her concern that “he might have thought I had let him down when I did not return” to the front-line region she was expelled from.[20]

Among Westerners in China, Jean Ewen knew Bethune better than anyone. She travelled with him for five months, across the Pacific beginning in January 1938, then on a marathon exodus from south to north China, pursued by the Japanese air force and army for much of it.

The two shared gruelling hardships, among them trekking on a mule caravan carrying medical supplies to the Eighth Route Army in Yan’an.

The pair also shared exhilarating highs, notably conversing with Mao Zedong through a long night immediately after their arrival at the remote headquarters of the Chinese Communist Party.

Unlike Bethune, Ewen had an excellent command of Chinese. Her manuscript recollection about that time is a fascinating portrayal of the terrible privations imposed on China by centuries of feudal backwardness and by the assault of one of the world’s foremost military powers of the day on a poor and poorly-armed country.

After more than a month of frustrating and exhausting travel, during which they were reported dead, they reached Xian. Bethune had been morose through times of enforced delay as they waited for a lull in the Japanese attack that would allow them to cross the Yellow River. In Xian, he was revived when he found kindred spirits in one of the founders of the Communist Party of China, Lin Beiqu, and the redoubtable General Zhu De. They were soon immersed in animated plans for hospitals in the front-line region of Wutaishan.

For her part, Ewen found a different release. She went shopping. Sick of her filthy uniform, she roamed the town, found a hairdresser and some cosmetic shops, then set out to buy a dress. She returned to their barracks wearing her prize, which she described in detail in her handwritten memoir and the published version, China Nurse: “a long blue sheath — Chinese style with a lace petticoat whose gossimer [sic] scallops peaked out of the slit on each side of the long skirt …” Under the circumstances, Bethune’s reaction was perfectly understandable, but it cut her deeply and confirmed for her his insensitivity: “Where the hell did you get that rig — it’s rather out of place.”[21] Bethune was baffled by the daughter of a prominent communist being, as she herself proclaimed, so bourgeois.[22]

The frequent quarrels between her and the man she later disparaged as “Big Norman” revealed much about their different orientations. She was resentful of his single-minded dedication to the wounded — during the trek from Hankou to Yan’an he used up their entire store of supplies, mostly treating hordes of ill and wounded civilians. Bethune seemed to be unperturbed that the Japanese were often perilously close, and, to the chagrin of Ewen and the caravan master, carried on attending to civilians, saying “never mind, we’ll make it.”[23] She took this at first to be evidence that he was “a doctor first — concerned only with the person who might be sick or wounded. … I assumed that somewhere under this obsession there was a human being. Later I wondered even about this.”[24]

Perhaps more galling to her were his communist convictions — he once gave her “a lengthy discourse on the virtues of [Communist Party of Canada leader] Tim Buck” — and the fact that “he kept hitting me over the head with my father.”[25] Tom Ewen’s loyalty to the CPC, which made his family “merely bystanders to the part he was playing in history,” was still a raw scar on his daughter’s heart.[26]

Ewen could give as good as she got. She confided to Bethune biographer Roderick Stewart that “I learned early to talk back to men — especially self-styled revolutionaries.”[27] And just as he sent her into convulsions with mention of her father, she — inadvertently or by astute insight into his life-long torment — bitingly observed that Bethune was “nothing but a bloody missionary.” No words could more stingingly have invoked for him the horrors of his missionary mother, whom he called “the dragon” and “a hellion.”[28] Predictably, he poured scorn onto Ewen for that taunt.

While the two travellers sparred over the other’s perceived and real weaknesses, like any couple on a road-trip from hell, they ultimately came to admit to a grudging admiration. Bethune, who was imbued with that era’s “doctor knows best” prejudices, paid her the highest compliment that he likely could envision coming from a surgeon. After two days of continuous surgery at Yan’an, Bethune took her aside and said “Nurse, I take back everything nasty I have said to you about your work, you are an excellent scrub nurse.”[29]

His lengthy despatches to Canada also consistently praised Ewen. Curiously, Bethune’s apology is recorded in her manuscript but didn’t make it into the published version of it, China Nurse. What did survive was his warning to her never to refer to him by his first name and not to offer a diagnosis of any patient’s ailment.[30]

Bethune lived with Ewen longer than he had with any other woman except Frances. Although theirs was never an intimate relationship, hardship and danger welded them closer together than might have been seen even between husband and wife. And in her manuscript and her subsequent correspondence with Roderick Stewart she was utterly candid.

Thus, her observations on two significant aspects of his character hold considerable weight. These were his drinking and his reputation as a womanizer. In a letter to Stewart in 1971, Ewen referred specifically to the scandalous stories attached to him. While proclaiming him to be “a lady’s man” at whom women threw themselves (where she observed this is not stated), she took pains to add that, “he was never debauched either with women or alcohol as far as I knew him in and on the way to China.”[31]

Conducting research for his first biography of Bethune, Stewart recorded a telling observation that Bethune never tolerated any situation in which he felt there was “a harness on him. Most women made that mistake.”[32]

Like women in Bethune’s life, historians have found it difficult to put a harness on him. In no way is Bethune more difficult to rein in than with regard to women. As on so many issues, the enigma of Norman Bethune persists there, too.

*

Larry Hannant is a history professor and an award-winning book author and website creator. He is an adjunct associate professor in the Department of History at the University of Victoria. He is the author of The Infernal Machine: Investigating the Loyalty of Canada’s Citizens (1995) and the editor of The Politics of Passion: Norman Bethune’s Writing and Art (1998), which won the Robert S. Kenny Prize in Left/Labour Studies in 1999, and Champagne and Meatballs: Adventures of a Canadian Communist (2011). Hannant researched and co-wrote a feature-length documentary film on the Doukhobors, The Spirit Wrestlers, which was broadcast on History Television in 2002. He is the director of “Explosion on the Kettle Valley Line: The Death of Peter Verigin” and “Death of a Diplomat: Herbert Norman and the Cold War,” two sections of the award-winning Great Unsolved Mysteries in Canadian History website. In addition to non-fiction books, he has published magazine and newspaper articles, as well as poetry and short stories.

*

[1] See, for instance, the direct quotes from what are purported to be “Ted’s notes dated February 10, 1937” in which Allan claims that he was greeted warmly on arrival in Madrid by Bethune. In fact, on that day Bethune was 500 kilometres away, tending to the tens of thousands of refugees who had fled the fascist assault on Malaga. http://www.normanallan.com/Misc/Ted/nT%20ch%201.htm

[2] The film was dogged by conflict during and after its production, and it is not today found on DVD or popular movie sites. However, a Spanish-language-subtitled version can be found online at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=bkshget9ZVc

[3] Libbie Park, “Norman Bethune as I Knew Him,” in Wendell Macleod, Libbie Park and Stanley Ryerson, eds., Bethune, The Montreal Years: An Informal Portrait (Toronto: James Lorimer, 1978), 98-9

[4] Park, “Norman Bethune,” 93

[5] Mrs. W. Pitfield to Roderick Stewart, May 17, 1971, Osler Library of the History of Medicine Archives, Roderick Stewart Fonds P89 Acc 637/1/57

[6] Park, “Norman Bethune,” 99

[7] Michael Petrou, Renegades: Canadians in the Spanish Civil War (Vancouver: UBC Press, 2008), 163-6; Michael Petrou, “Sex, Spies and Bethune’s Secret,” Maclean’s, October 24, 2005, 51

[8] Jan Kurzke and Kate Mangan, “The Good Comrade,” Jan Kurzke Papers, International Institute for Social History, Amsterdam, 240, and excerpts from the manuscript provided to the author by Charlotte Kurzke; Virginia Cowles, Looking for Trouble (New York and London: Harper and Bros., 1941), 32

[9] Norman Bethune’s personnel file, “Report on the Performance of the Canadian Delegation in Spain,” April 3, 1937, Library and Archives Canada (LAC), MG10-K 2, 545/6/542, reproduced in Larry Hannant, ed. The Politics of Passion: Norman Bethune’s Writing and Art (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1998), 361-4

[10] For a succinct summary of von Rothman’s contributions, see Paul Preston, We Saw Spain Die: Foreign Correspondents in the Spanish Civil War (London: Constable and Robinson, 2008), 115-8

[11] Kurzke and Mangan, “The Good Comrade,” 240

[12] Preston, We Saw Spain Die, 104

[13] David Lethbridge, Norman Bethune in Spain: Commitment, Crisis, and Conspiracy (Brighton: Sussex Academic Press, 2013), 125-6

[14] David Crook, “Hampstead Heath to Tian An Men,” http://www.davidcrook.net/pdf/DC06_Chapter3.pdf, 17

[15] Larry Hannant, ‘“My God, are they sending women?’: Three Canadian Women in the Spanish Civil War, 1936-1939,” Journal of the Canadian Historical Association, vol. 15, n° 1, 2004, 164-5

[16] Tom Newnham, Dr. Bethune’s Angel: The Life of Kathleen Hall (Auckland, NZ: Graphic Productions, 2002), 104

[17] Newnham, Dr. Bethune’s Angel, 111-2

[18] Cited in Larry Hannant, ed. The Politics of Passion: Norman Bethune’s Writing and Art (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1998), 351. Emphasis added.

[19] Newnham, Dr. Bethune’s Angel, 139. Munroe Scott’s McClure: The China Years of Dr. Bob McClure (Toronto: Canec, 1977), 230, lays out the Christian contempt for Bethune and his unapologetic communism. In the course of a 500-kilometre rail trip, McClure halted briefly at Tongguan Station, where he was summoned to help find an apparently lost Bethune. Jean Ewen, who spoke Chinese fluently and was on the journey with Bethune, is not mentioned. Bethune was located in the town, rather the worse for alcohol but “still functioning,” and he and McClure had a difference of opinion over Canada’s self-righteousness, the medical system in Canada and communism.

[20] Cited in Newnham, Dr. Bethune’s Angel, 147

[21] Jean Ewen, China Nurse, 1932-1939 (Toronto: McClelland and Stewart, 1981), 81-2; handwritten manuscript “You Can’t Buy It Back,” 70-71 in the author’s possession, courtesy of Laura Meyer. The page numbers of the manuscript – some pages of which are typed while others are handwritten inserts – are not reliable.

[22] Ewen, “You Can’t Buy It Back,” 339

[23] Ewen, China Nurse, 66

[24] Ewen, China Nurse, 63

[25] Ewen to Roderick Stewart, March 7, 1972, Osler Library of the History of Medicine Archives, Roderick Stewart Fonds P89 Acc 634/1/108

[26] Ewen, China Nurse, 10

[27] Ewen to Stewart, March 7, 1972, Osler Library of the History of Medicine Archives, Roderick Stewart Fonds P89 Acc 634/1/108

[28] Lethbridge, Norman Bethune in Spain, 2013), 3-11; “Gordon’s Notes,” 2, Osler Library of the History of Medicine Archives, Roderick Stewart Fonds, P89 Acc 637/1/57. Alone among Bethune’s biographers, Lethbridge has perceptively turned the focus of Bethune’s psychological makeup from his father to his mother, and in doing so has opened up a hitherto-ignored aspect of Bethune’s character.

[29] Ewen, “You Can’t Buy It Back,” 189

[30] Ewen, China Nurse, 60; “You Can’t Buy It Back, 47

[31] Ewen to Stewart, attachment to letter of November 11, 1971, Osler Library of the History of Medicine Archives Roderick Stewart Fonds P89 Acc 634/1/108

[32] “Gordon’s Notes,” 3, Osler Library of the History of Medicine Archives, Roderick Stewart Fonds P89 Acc 637/1/57

*

The Ormsby Review. More Readers. More Reviews. More Often.

Reviews Editor: Richard Mackie

Reviews Publisher: Alan Twigg — BC BookWorld / ABCBookWorld / BCBookLook / BC BookAwards / The Literary Map of B.C. / The Ormsby Review

The Ormsby Review is a new journal for serious coverage of B.C. literature and other arts. It is hosted by Simon Fraser University. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Robin Fisher, Cole Harris, Wade Davis, Hugh Johnston, Patricia Roy, David Stouck, and Graeme Wynn.

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

Leave a Reply