#19 Trade Unionist Harvey Murphy

September 22nd, 2016

By Ron Verzuh

Harvey Murphy is not a name that echoes loudly throughout the annals of 20th-century British Columbia labour history. In fact, the tireless trade union organizer, negotiator, and active Communist Party of Canada (CPC) bureaucrat has almost disappeared from most histories of the Canadian labour movement. A brief study at the very active life of the man who called himself the “reddest rose in the garden of Labour” suggests that he merited more than a few paragraphs or a few pages in scholarly works dedicated to a study of labour’s past.[1] And yet Murphy, who stood at the barricades of many labour struggles throughout an era of radical union and left politics, seldom receives more than footnote-length treatment. Hated by some labour leaders, he was long deemed a workers’ friend by Alberta and BC mine and smelter workers. He was at the clamorous forefront of the struggle for union and worker rights in Canada’s West for more than a decade. Why then has so little attention been paid to a man that BC historian Allen Seager called “the most influential communist in the Canadian trade-union movement in the 1940s”?[2]

At the risk of stating the obvious, one answer may be simply that he openly declared himself a life-long Communist at a historic moment when adhering to such a political belief system would soon be reviled by many. Another over-simplified answer is that he was a dislikeable, “belligerent, often inebriated, rabble-rouser.”[3] A third reason for the lack of attention might have to do with his reputation as a behind-closed-doors deal maker and organizer who did what he wanted in spite of the law or the dictates of the CPC leaders who sometimes saw him as more a hindrance than a help.[4] Some of his early organizing efforts drew angry rebukes from party apparatchiks.[5] Leaders of the Canadian Congress of Labour (CCL) and the Trades and Labour Congress (TLC), the two central union federations, also viewed him as a liability. He had reputation as a committed and accomplished industrial organizer with an enviable talent for swaying opinions in the backrooms and the union convention halls. But he openly criticized CCL president Aaron Mosher and other labour leaders for failing to more actively organize workers and assist the unemployed. Such behaviour did not make him a desirable subject for official union or party histories.

But there is more to Murphy than those simple responses would suggest and still only a few historians have bothered to document his life and Communist times. Two stand out: Lita-Rose Betcherman, who wrote about the exploits of the young Murphy, and Stephen L. Endicott, who provided background on Murphy as a WUL organizer in Alberta and eastern British Columbia.[6] So who was this person the press often dubbed Canada’s No. 1 Red agitator? Who was the man RCMP commissioner Cortlandt Starnes labelled a “persistent, reckless and dangerous agitator”?[7] Who was this “proletarian Cromwell,” as CPC national executive member and sarcastic poetaster Malcolm Bruce once described him?[8] And what role did he play in BC’s rough and tumble left-labour community of the 1940s and Cold War 1950s?

Most Murphy observers are of mixed opinion when assessing his life. Historian Bryan Palmer, for example, called him “a bombastic blend of talent and chutzpah.”[9] Communist BC lawyer John Stanton claimed that he had “a more than generous ego and a certain foxiness,” but also suggested that he had an “engaging personality and was an excellent orator.”[10] C.S. Jackson, Communist leader of the radical United Electrical Workers’ union (UE), acknowledged Murphy’s pivotal role in defining how radical Canadian unions like Mine-Mill and the UE should address national issues like unemployment and international ones like peace and disarmament.[11] BC CPC leader Maurice Rush credited Murphy as “one of the most capable tacticians in the labour movement,” one given to “great strokes of genius often inspiring those who worked with him.”[12] A biography of the CPC’s dynamic Ontario organizer, J.B. “Joe” Salsberg reveals that Murphy was considered among the “real” leaders of the Labour-Progressive Party (LPP), the CPC’s name after it was banned.[13]

Others were less complimentary. The federal government, for example, viewed him mistakenly as a risk to national security. Employers saw him as a possible threat to their profit margins and a danger to the economic growth of the community. Leaders of the nascent Cooperative Commonwealth Federation (CCF), men like BC member of Parliament Angus MacInnis, a founder of the party, saw Murphy and his ilk as a serious impediment to their quest to become Canada’s chief left-wing voice in the provincial legislature and the federal Parliament. Murphy was, indeed, a man at the centre of the political storm in BC for more than a decade and he had made plenty of enemies along the way.

Murphy first arrived in the Pacific province for a prolonged say starting in late 1942, but his first appearance came much earlier. While still working as an organizer for the Workers’ Unity League (WUL), a CPC-initiated industrial organization, he secretively crossed the Rockies to participant in labour conflicts during the Great Depression. By spring 1943, he had moved to Vancouver as western district director of the International Union of Mine, Mill and Smelter Workers (Mine-Mill). His visits to BC’s mining communities and his even earlier association with miners and smelter workers elsewhere in Canada, prepared him well for his future role as Mine-Mill’s top leader in BC.

***

He was a boy of seven or eight years old when he arrived in Canada from Poland in 1913 or 1914. The original family name was Chernikovsky, but in his twenties he borrowed his Irish name joking that it would keep him out of trouble with the anti-immigrant authorities.[14] His father Solomon was a factory worker in Kitchener, Ontario, where Murphy got his early jobs in making buttons and rubber products. Solomon moved the family to Toronto to open a kosher butcher shop in the Kensington market area after the First World War.[15] Soon, however, young Harvey, dissatisfied with his father’s strict Jewish household, was spending time with Tim Buck, a trade unionist who was destined to lead the CPC. Some observers said he was “almost ‘raised’” by Buck and could be seen regularly hobnobbing with Communist firebrands like Becky Buhay.[16] Not surprisingly, at sixteen he joined the CPC.[17] Soon he was acquiring experience in defying government authorities, confronting trade union leaders with whom he disagreed, and confounding employers.

In his early twenties he had already become a recognized heckler at protest rallies and marches in Ontario and had made forays into the eastern United States to join strikes in the mining and auto industries. Here and afterwards he got his first taste of underground union organizing, company unionism, and employers’ use of labour spies. As early as 1929, when Murphy was still in his twenties, police began to meticulously track his movements. The resulting first police file, compiled by the Prince Rupert, BC, detachment, described a man who walked “with a slouch” was “coarse,” with “no set home,” and whose habits included smoking, drinking, gambling, and playing pool. He was an “auto labourer” affiliated to the Young Communist League (YCL) and was “extremely friendly” with various CPC leaders. The profile stipulated that he was a “minor” influence as an agitator.[18] Over the next few years, however, police profiles changed markedly as the officers assigned to him followed the CPC vagabond on his frequent forays into BC to join historic strikes. By spring 1933, a revised police profile noted that he “walks like a sailor– legs astride” and was “almost Jewish in appearance.” The profile further described him as “clean-shaven,” “well-dressed,” and a “very good speaker.”[19] His organizing talents were honed in these years by his work with unemployed associations and the WUL. In 1930 he came to Alberta to work with the WUL-affiliated Mine Workers of Canada (MWUC) where he attracted even greater police notice. The new location also accommodated a courtship with his eventual wife Isobel as well as frequent sallies into BC.

In 1933, for example, Murphy had supported striking copper miners at the company town of Anyox near Prince Rupert. Strikers at the Granby Consolidated Mining, Smelting and Power Company demanded improved working and living conditions. A Navy vessel, the Malaspina, assisted provincial police who arrested strikers and shipped them to Prince Rupert and Vancouver, but the strike continued.[20] Then Granby brought in scabs from Vancouver and the strike was eventually lost, but Murphy had earned more respect for engaging in the fight and for going to jail. In 1935, he was again back in BC for yet another strike, this time at the company town of Corbin. As part of his continuing association with the MWUC, whose Blairmore, Alberta, local had been sending money and other forms of strike support to the Corbin miners, Murphy embraced the task of exposing the horrifying conditions in the mountain town. Mining militants, led by Murphy and leaders of the MWUC, marched uphill for ten miles to mount a protest at Corbin.

At the B.C. border, they were met by a party of R.C.M.P. armed with a loaded Lewis gun. Desperate revolutionaries though they were, the miners’ leaders decided to negotiate. Faced with the possibility of a massacre much worse than that at Estevan, both the union and the red coats compromised. While the “army” would have to stay in Alberta, a ten-man delegation, including that number one undesirable citizen, Harvey Murphy, was escorted into Corbin.[21]

As they did during earlier strikes, mine workers’ wives faced off with the company, American-owned Corbin Collieries Ltd., in a strong show of support for the strikers. Communist writer and poet Dorothy Livesay recounted what one striker observed:

The womenfolk were grouped in the middle and some were up front. Suddenly, as at a signal, the full detachment of police ran out from the hotel and grouped themselves in two squads on either side of the caterpillar, flanking the picket line…Before we could understand anything the caterpillar was moving forward, straight at our women. And the police, instead of clearing the way, suddenly closed in, hemming us in on both sides, beating miners and their wives with pick handles and riding crops.[22]

If Murphy had participated in 500 strikes to that point, as has been suggested, the Corbin fight had to be one of the most vicious of those confrontations.[23]

Again in 1940, Murphy was immersed in a historic BC labour dispute, this time at Pioneer Mine in the Bridge River district around Lillooet. He arrived on the scene of what has been called Canada’s first sit-down strike to face an unusual situation. The sit-downers, who were not unionized, stopped all transportation in and out of the mine ostensibly to force recognition of what they were calling the Canadian Mine Workers Union. The crew aboveground, some of them trying to organize a legitimate union, opposed the sit-down strike tactic, as did Murphy, and were being called scabs.[24] Murphy was tasked with organizing this group after the company stopped the sit-down with help from the BC provincial police. Secret police bulletins erroneously reported that the strike was illegal, calling their demands “ridiculous.” Warrants were issued for the arrest of six of the strikers.[25] Murphy, would oversee the formation of a Mine-Mill local at Pioneer and help carry on the fight by a now legitimate union. The Pioneer strikers garnered support from the CCF and other unions, including Mine-Mill Local 480 in Trail which claimed the strike was illegal and called on BC labour minister George Pearson to end the court proceedings against the six strikers and charged that he was aiding and abetting “war profiteering.” Local 480’s newspaper, The Commentator, argued that the “yellow press” were also guilty of same, having devoted “enough news on the Pioneer strike to gag a rhinoceros.”[26] The paper concluded that “these fighters…are on strike for workers’ rights and a decent living standard and against the war profiteers.”[27] Workers at Bralorne, said to be the richest gold mine in Canada at the time, were also on strike but encouraged by Murphy they managed to find resources to support the Pioneer miners as did other Mine-Mill members.

Murphy’s strike participation in BC slowed with the start of the Second World War and was completely curtailed soon after Hitler invaded Russia in June 1941. With the Hitler-Stalin non-aggression pact of 1939 at an end, the Communist International organization or Comintern once more issued a policy change. First ordered to oppose the war as imperialistic, now Communists everywhere shifted to a pro-Allied policy position. Regrettably for Red activists, the CPC’s change of heart was of no help in protecting them from the Communist-hunting authorities. Murphy was apprehended in Toronto on 4 November 1941.[28] Under the War Measures Act he faced allegations from the Defence of Canada Regulations (DOCR) advisory committee about his life’s work as a Communist union organizer.[29]After an arduous interrogation, he was moved to a Hull internment camp where the authorities made no distinction between Reds, fascists, and other undesirables housing them all together. For a time Murphy worked in the kitchen with Pat Sullivan, a leader of the Canadian Seaman’s Union (CSU) and a future Murphy detractor.[30]

Upon his release in late 1942, Murphy attempted to sign up with the Canadian armed forces, but was rejected because he was a Communist. He then travelled back to Alberta to rejoin Isobel and son Rae and to search for work, but he was refused a job in the mines even as a labourer. He borrowed enough money to travel to Vancouver where he found work and joined what he called “the great labour movement in BC.”[31] In observing an attempt to organize the shipyards into one big industrial union under the Congress of Industrial Organizations (CIO), he remembered that it “was a time of mass organization.”[32]

As a CPC organizer dedicated to the CIO’s no-strike pledge pledge, Murphy tried to prevent them but workers walked off the job anyway. It was at one of these walkouts at Copper Mountain near Princeton, BC, that he first got involved with Mine-Mill, the union he would work with for much of the rest of his life, rising to the influential post of western region director. Chase Powers, Mine-Mill’s staff member in District 7 with headquarters at Spokane, Washington, described the initial engagement:

He come out of there, and he went up to do Copper Mountain, which is back in the mountains about 4-5,000 feet. And this is in March, and it’s blizzards up there. Had to help him get an overcoat. And he went up there, didn’t wait for anything…in the afternoon, and took a train that night. Got up there, went to Copper Mountain. Two days later, he’s back, both hands full of money. “What’ll I do? They all signed up.”[33]

Murphy remembers the moment somewhat differently and provides more background to the dispute. He was to enter the company town where the strikers were protesting that Granby, the same company that had dealt so harshly with workers during the Anyox strike several years before, had failed to provide electricity for their company houses. As Murphy recalled the 1943 setting,

The offices and the mine and some of the bunkhouses had electricity but the houses didn’t…Some government control board would allocate the copper cable and wire needed to electrify the camp. Here the mine was turning out tons of copper and they couldn’t get the scraps of copper they needed to string a few wires to the houses.[34]

By the time Murphy arrived, the workers had refused to join a nascent company union but had not yet replaced it with a legitimate one. It was a prime opportunity for Mine-Mill, then suffering from several setbacks, notably the loss of the historically significant 1941 Kirkland Lake, Ontario, strike.[35] Mine-Mill needed to regain its footing in BC as a mining and smelting union and it was Murphy’s job to initiate the renewal by ending the strike and establishing a Mine-Mill local, which he promptly accomplished.

According to Murphy, it was the first new Mine-Mill agreement to be signed in Canada at that time. Workers from other mines in the area had heard about the Copper Mountain settlement and were keen to meet Murphy to discuss creating Mine-Mill locals of their own. A week later, Murphy set out for Trail where his future course as a Communist union organizer for Mine-Mill was about to increase his public profile and provide more ammunition for his enemies inside and outside the labour movement. His mission was to organize the giant smelter owned by the Consolidated Mining and Smelting Company of Canada (CM&S) and associated mining operations in the Kootenays that were satisfying Allied demand for lead, zinc, fertilizer, and other military ordnance. Success there could ensure that Mine-Mill gained the foothold it needed to survive in BC.

***

Murphy’s years as a chief union negotiator for Local 480 in Trail began in late March 1943 when he arrived in the midst of an organizing campaign that had been foundering since late 1938 after a summer conference of BC mining unions had assigned Communist Arthur “Slim” Evans to organize a CIO union. The smelter workers, among them a smattering of Communists, had long been disgruntled with the paternalistic style of company president S.G. Blaylock, the company union he had fostered after the First World War to stifle union organizing, and the company-town environment he had created. The arrival of an avowed Communist may have unsettled Blaylock and reminded him of his earlier confrontations during the 1917 smelter strike. Murphy might have reminded the company president of the difficult confrontations he faced with socialist Albert “Ginger” Goodwin, the strike leader who became a labour martyr. It may also have rekindled more recent memories of Evans, a well-known Red radical who had spearheaded the famous On to Ottawa Trek in 1935. During the war years, as Trail historian Elise G. Turnbull has noted, Blaylock was deeply concerned that “people were leaning toward a socialistic state.”[36] Murphy was a new source of that concern.

Well fortified from his earlier confrontations with company unions and recalcitrant employers, Murphy was charged with signing up a majority of smelter workers and filing for union certification with the BC Labour Relations Board (LRB). Assistance came in the form of the recently amended BC Industrial Conciliation and Arbitration Act (ICA 1943) that had banned company unions. The act did not stop Blaylock supporters from creating other barriers to the Mine-Mill union drive, but it did ensure that there was no longer a fear of joining the union and the membership list quickly grew. As historian David Michael Roth has documented, the “new act served as a catalyst, pushing union activism to the forefront in the company town.” [37] But it would do nothing to protect Communist union organizers like Murphy from anti-Communists in the smelter city.

In June 1944, he launched the BC District Union News, a newspaper that would serve for the next ten years as the primary voice of Mine-Mill in the province.[38] Allied with Local 480’s Commentator, Murphy had the tools he needed to counter the anti-union and anti-Communist Vancouver dailies as well as the Trail Daily Times where editor William Curran ceaselessly advised his readers to avoid unions and to beware of Red outsiders like Murphy. The mainstream media were relentless anti-CIO campaigners, but the Mine-Mill director was well equipped for the journalistic task at hand, having already written for Communist papers like The Worker for many years.[39] Despite his low level of education – he quit school at 16 – he was a capable labour writer and editor. Among his first front-page stories, the District News gleefully announced that Blaylock had reluctantly acknowledged that Mine-Mill was the legal bargaining agent for the workers at the Trail smelter.[40] Murphy’s editorials might have helped nudge the CM&S, with Murphy exposing Blaylock’s seeming disregard of both the ICA Act and federal Order-in-Council PC 1003 that provided legal bargaining rights for unions.

Murphy inserted cartoons like this in his District News to fight for miners and smelter workers. Courtesy USW.

On 16 January 1945, Murphy and Blaylock signed the first formal collective agreement “ever consummated by the C.M.S. Company and a legitimate union.” It replaced the working agreement signed six months earlier. Now working conditions were further fleshed out. It might have made Murphy pause to rest.[41] After all, as chief negotiator for Kimberley’s more than 1,000 Sullivan Mine workers and the more than 4,000 smelter workers of Trail he had won them better vacations with pay, better overtime provisions, improved seniority, and a promised end to the company’s unwieldy and unfair wage bonus plan. A few weeks later, Murphy hired Claire Billingsley as the international Mine-Mill representative for the district. In his column, he boasted that Billingsley was “a tower of strength for Local 480.” But it was all wishful thinking for soon the Saskatchewan-born smelter worker was using that strength to undermine everything Murphy and Local 480’s Red activists had accomplished since the union organizing drive began.[42]

In May, with the war just ended in Europe, Murphy focused on maintaining vigilance regarding Mine-Mill’s no-strike pledge until Japan had surrendered. He was also visiting communities in the neighbouring East Kootenay region to campaign as the Communist candidate in the historic 1945 federal election. His candidacy, one of 68 fielded for the party, won praise from one of his regular columnists at the District News, “The Tired Mucker,” who aggressively advised the people of the riding to vote for Murphy because he “has gone to prison for us, more than once.”[43] Alas, on Election Day, 11 June, the voters failed to elect Murphy to go to Ottawa on their behalf. He did garner 1,632 votes (12.76 per cent of the popular vote), a thousand votes ahead of the Social Credit candidate, but he lagged far behind the winner, CCF candidate James Herbert Matthews with 4,712 votes (36.85 per cent). Murphy took some consolation in that it was “a distinct gain and most of the votes came from the miners, loggers, and railroad workers,” and it was true that he had received a majority of votes in mining towns like Fernie, Natal and Michel. Murphy used his column to dispute the vote count and made a call for support of the CCF breakaway party, the People’s CCF, and candidate Bert Herridge as they entered the BC election that October with full support from Local 480 and the workers of Trail.[44]

Murphy’s LPP candidacy was hardly among the reasons that the 1945 election was considered historic. That status would partially rely on the re-election of Communist Fred Rose, first elected to Parliament in a 1943 byelection in the working-class Montreal riding of Cartier.[45] The Rose re-election accompanied another related historical development. In autumn 1945, Soviet cypher clerk Igor Gouzenko defected and named Rose as a Soviet spy. Some saw it as the beginning of the Cold War in North America and licence to intensify pressure on Murphy and his comrades in the BC trade union movement. Also significant, in November Blaylock died. The CM&S president had preferred to leave the anti-Red diatribes to the loyal Times editor Bill Curran. Now, however, his company was emboldened to oppose Communism more vigorously and publicly.

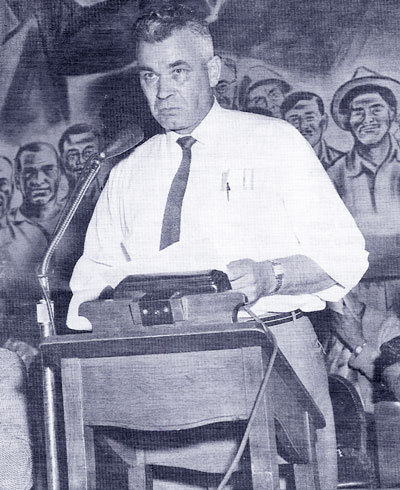

Murphy acted as chief union negotiator for Local 480 at the Trail smelter. Courtesy Trail Historical Society.

In 1946, Murphy cemented a collective agreement with the CM&S that eliminated a pay bonus plan, based on “complicated algebraic formulas,” and instituted a more equitable wage system. If company management had not disliked Murphy before this union victory, they certainly did so now.[46] The employers “dispute my whole personal life,” Murphy wrote. “This is the old stunt of launching personal attacks on union officers because the employers do not wish to face the real issues.”[47] The CM&S pact, said by the district union to be of “national importance,”[48] freed Murphy and Local 480 to assist with a province-wide 13-local strike in BC’s gold and copper mines, part of a major post-war strike wave in Canada to win back some of what workers had sacrificed to beat the Axis powers. The smelter union and Murphy also acknowledged the supportive role played by Trail’s Ladies Auxiliary Local 131 during the long strike, noting that the women stood “staunchly beside our brothers.”[49] When the miners’ strike ended in October, Murphy and other BC Communists would soon face a bigger threat, especially from south of the border.

With the passage in the US of the anti-Communist Taft-Hartley Act the following summer as a way for the business community to redress the pro-labour Wagner Act of 1935, new enemies of Communist trade unionists surfaced to publically attack them. One anti-Red attack came from an unexpected quarter. Mary Orlich, a Butte, Montana, miners’ wife and international president of Mine-Mill ladies auxiliaries, lashed out at Mine-Mill Reds in an interview with the Saturday Evening Post in which, among other criticisms, she contended that “when the commies are in the picture, nobody wins.”[50] Murphy and members of several Mine-Mill ladies auxiliaries angrily discounted the Orlich interview, arguing that it was her and not the “commies…who are the stooges of Big Business.”[51] Nonetheless it had the potential to create more doubts about the CPC and Murphy in the minds of smelter wives.[52]

While Taft-Hartley had no jurisdiction in Canada, BC’s 1948 ICA Act revisions seemed to union leaders, especially “virulent opponents” like Murphy, to present a similar anti-union-undermining intention.[53] Posing as labour legislation designed “to protect the membership of unions from their officers,” it was for Murphy “a green light to smash unions.”[54] The revised law (Bill 39) had the added effect of emboldening anti-Communists across the spectrum of Murphy detractors. As one District News writer explained:

In line with the current wave of hysterical anti-labor campaigns arising out of passage of the Taft-Hartley Bill in the United States and our own Bill 39 in British Columbia, to say nothing of the continuous sniping of the Committee on Un-American Activities, aimed at smashing labor unions and discrediting their leaders, the one time eminently respectable and conservative publication, Engineering and Mining Journal, has now come forth with an article with the intriguing title “Communism Menaces the Mining Industry.[55]

Inside Local 480, the legislation was having a similar negative effect. The company union established by Blaylock after the First World War was illegal under the earlier ICA Act, but a new Independent Smelter Workers Union (ISWU) had appeared to replace it with many of the old Blaylock supporters on the executive. More frustrating for Murphy, Billingsley, who had left his union rep’s job, had been elected president of Local 480. With help from the ISWU, Billingsley had strengthened his voice as an anti-Communist just as North America was entering the age of McCarthy. Soon he was orchestrating a takeover of the Mine-Mill local by the United Steel Workers of America (USWA). Almost as frustrating for Murphy perhaps were the actions of CPC member Jack Scott, a fiery militant from Vancouver who did not appreciate Murphy being “lord of all he surveyed” when the district director assigned him to clean up the Trail local and the small Communist club there.[56]

Despite his noted animosity toward Murphy, Scott was a solid trade unionist and a loyal Communist. Other Murphy enemies, some of them bitter ex-Communists, would use the mainstream press to speak out against Murphy and other Red union leaders. John Hadlun, for example, a former MWUC member, claimed to a Trail audience that he had attended the International Lenin School (ILS) while Murphy was there and that they were trained in espionage. He later published his accusations against Murphy and others in a series of articles in Maclean’s under the title “They Taught Me Treason.” Pat Sullivan, mentioned earlier, caused an even bigger sensation when he claimed that Murphy and many other Red unionists were destructive forces within the movement and in society.[57] Murphy argued that this anti-Red campaign in the press and on radio was meant “to divide workers on the issue of Communism [but it] has not succeeded.”[58] It did, however, energize others to level criticisms against Communists, especially Murphy, a self-appointed open target.

The CM&S, which, as mentioned, had previously been content to let the Trail Daily Times fight its ideological battles with the CPC, released a booklet in March 1948 innocuously called Your Union and You. In it, and in a broadcast on local radio station CJAT, the company’s assistant-manager-to-be, William S. Kirkpatrick, warned that Mine-Mill Communists like Murphy were “working vigorously and continuously to destroy our freedom.” Local 480’s Al King called the booklet, “a blatant management attempt to urge union members to get rid of any suspected Communists in their union.”[59] But it helped CCL leaders, led by Charlie Millard, head of the USWA in Canada and a life-long Red hater, who were anxious to discredit Murphy and other Red organizers. Millard, a CCF man, was also at loggerheads with Murphy over CCL support for the CCF as labour’s party.

In April, he and other CCL leaders got their chance when a drunken Murphy stood up at a labour lobby banquet in Victoria, BC, and criticized the leaders for not defending Mine-Mill international president Reid Robinson who was again being deported from Canada as an alleged Communist. The incident, known in labour circles as the “underpants speech,” led to a two-year suspension for Murphy as a vice-president of the BC Federation of Labour. As Al King remembers the speech, Murphy “told the full meeting that if Mosher was going to kiss the boss’s ass, he better be sure to pull his pants down first.”[60] Even fellow leftist Malcolm “Red Malcolm” Bruce, once Murphy’s friend, charged that his comrade’s comments were “wholly indecent and inexcusable.”[61] As shipyard union leader Bill White explained, “You hear people blame the downfall of the Communist Party on Murphy’s Underwear Speech, but Christ, they were just waiting for any phony goddamned excuse and that happened to be it.”[62] The affair added new impetus to the CCL’s plans to purge its Communist-led affiliates. If there were remaining doubts that leaders of the BC labour movement wanted Murphy and Mine-Mill out of trade unionism altogether, they were now laid to rest.

The Times, relishing a Red smear campaign and often in lockstep with the company, fervently continued its Red-baiting attacks. In a February 1949 edition, for example, the editor asked rhetorically, “Do Reds Run Local 480?” noting that Murphy was telling smelter workers that “this communist stuff is a lot of hooey.”[63] Murphy was used to dodging anti-Red critiques. Mine-Mill lawyer John Stanton, who would later become a vocal Murphy critic himself, explained that Murphy was hardly on the run despite the growing chorus of Red haters. The Mine-Mill western director

related well to working people, who enjoyed his gravelly-voiced exposes of the greed and stupidity of certain employers and politicians. No matter what difficulties Murphy faced, he always seemed to land, cat-like, on his feet. His more than generous ego and a certain foxiness were so noticeable that one could never be quite sure where one stood with Murphy.[64]

Scott was to test that foxiness whenever the chance arose, but now he would again fall into the Times’s anti-Red sphere after he was fired along with three other smelter workers, including Local 480’s first president Gar Belanger, also a Communist, for distributing two articles from the Communist Pacific Tribune that were critical of the CM&S Company.[65] Some observers claimed that the articles by Communist writer Bruce Mickleburgh showed that Blaylock was partially responsible for the shooting death of Ginger Goodwin, a claim that cannot be proved. Murphy angrily denounced the firings and the arbitration hearing that upheld them, arguing that it “sets a new standard whereby every worker in the employ of the CM&S is under constant threat of dismissal 24 hours a day wherever he may be.”[66] Company appointees to the arbitration board no doubt noted the hostility in Murphy’s minority report.

Murphy would again condemn the CCL’s top leadership, among them Steel’s Millard, for “openly collaborating with the employers” and for trying to take “control of the progressive unions and turn them into company unions for the boss.”[67] He further enflamed the CIO leadership by accusing president Philip Murray of perpetuating “gangsterism” and fraternizing with the Ku Klux Klan during the 1949 Steel raids in the US and a massive organizing drive in the southern states. “Today in the name of the CIO a split has been organized between Negro and white workers, from which only the employers can benefit,” Murphy wrote in his column.[68] Millard was centred out for more verbal whipping when he wondered aloud to the press whether shorter working hours would not lead to more beer drinking. A poet took up the issue in Murphy’s District News:

On Friday night when Charlie meets,

The Temperance Union girls,

He smiles and bows,

And tosses back his curls.

He tells them that his role in life,

Is keeping workers pure,

And in his hands,

The morals of

Our people are secure.[69]

Meanwhile, Billingsley was back in the news with a complaint against Murphy for suggesting that Local 480 had been colluding with the Times.[70] Billingsley was understandably upset when Murphy seemed to manipulate the district union election results giving Communist Ken Smith the presidency over the Local 480 leader.[71] The year closed on a low note for Murphy with the Steel raiders poised to launch their assault on the smelter workforce. The groundwork for the raid had been laid for Mine-Mill’s suspension from the CCL, possibly in part due to the fallout from Murphy’s underpants speech. Now Murphy’s biggest challenge in Trail was the destruction from within of Local 480, his largest Mine-Mill affiliate and one of which he was most proud.[72] But other forces were also pressing the CCL leadership to clear out its Communists, which they did in late 1949 and early 1950 with purges of all eleven unions suspected of having Communist leaders.

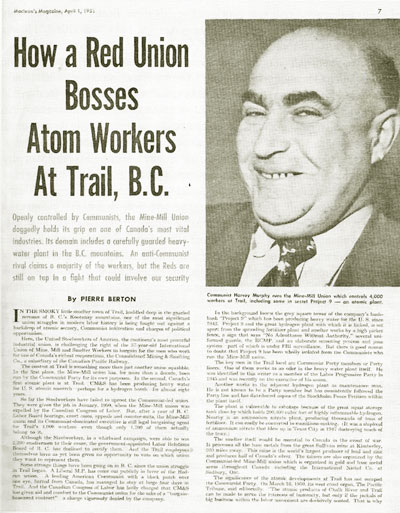

When the Steelworkers raid was at its peak in Trail, Maclean’s writer Pierre Berton attacked Murphy.

In February 1950, with Billingsley working overtime to bring his membership under the Steel banner and raiding the union dues war chest to do it, Millard and his team, sanctioned by the CCL-CIO, declared open warfare on Mine-Mill. It was to be a war using Red-baiting tactics aimed directly at Murphy, King, and a few other top organizers. As King noted, Steel was “using the red bogey and also trying to make it appear that Harvey Murphy is the issue.”[73] What ensued was a three-year raid that ultimately failed with a majority of Trail workers dismissing the USWA’s Red-baiting tactics and refusing to embrace the “dictatorship of Millard and his raiders.”[74] Murphy called it “a cold-blooded sneak raid” that would backfire. Kootenay East Liberal MP Jim Byrne, a member of Mine-Mill Local 651 in Kimberley, supported Local 480 and defended his union against Vancouver CCF MP Angus McInnis, an old Murphy adversary, in the House of Commons.[75] Murphy could also count the ladies auxiliary among Mine-Mill supporters. “Scores of women have joined the auxiliaries,” he noted, “and you should hear the radio broadcasts put on by the women themselves.”[76]

But the Steel raiders would not give up easily. And now, too, would come a new ally in the form of a third critic from within the CPC. Former Communist Gerry McManus, also of the Canadian Seaman’s Union, made the sensational claim that “the reds are ready to wage war inside Canada,” adding to the fervour building against Murphy and his comrades.[77] Exacerbating their political problems, Local 480 leaders endorsed the Stockholm Peace Petition and helped form the Trail Peace Council at time when peace had become a Cold War political football with media and politicians declaring it a Communist plot.[78] Murphy supported the local by publishing regular items on the evils of the atomic bomb in the District News. He also condemned the Korea War, as a Cold War-driven conflict in which Canadian troops were serving and dying. Although McCarthyism had no official role in Canada, with each Murphy commentary about the Cold War came renewed barrages of anti-Communist salvos from the Times and other media outlets. Murphy published a lengthy editorial, arguing that the union was being “attacked so hard in the capitalist press with lies and slander” because Mine-Mill was “a damn good union.”[79]

On April Fool’s Day 1951, one such attack came from the pen of Pierre Berton who would years later become one of Canada’s celebrated journalists, a television celebrity, and a popular historian. It came in the form of a feature article in MacLean’s magazine that offered a colourful though apocryphal depiction of Communists controlling workers at a secret plant at the Trail smelter that produced heavy water to be used by the Manhattan Project to produce the atomic bomb. The article was published just as the Steel raid was in full progress thus adding to the fervour of the campaign to discredit Murphy, “one of the top Party members in Canada,” and the Local 480 Communists.[80] The tongue-in-cheek response in Murphy’s District News “asked if the Steel Workers were paying his [Berton’s] expenses in coming here to Trail” and lampooned his stay, noting that Maclean’s must have issued him “scarlet-colored glasses” to protect him from the “tinge of pink” to be found in the smelter city.[81] Berton’s biographer argues that the famous writer was “no red-baiter,” but the article seemed to suggest otherwise. As A.B. McKillop noted, the Steel raiders disliked Murphy and they “were bent on getting rid of” this “leading Canadian Communist.”[82] At the time at least, Berton seemed equally bent on assisting with that goal.

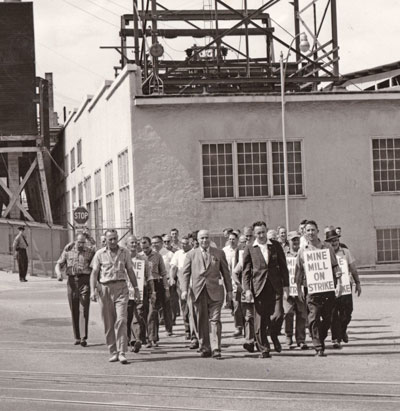

Murphy walked many picket lines while in BC. including with Local 480 members outside the Trail smelter in the 1950s. Courtesy USW Local 480.

Despite losing an LRB vote on representing Trail workers, Steel brought in new raid staff to continue what Murphy had called was a bought-and-paid-for jurisdiction. He would later highlight a Vancouver Sun article claiming that Steel had paid the CCL $50,000 for the right to raid. This “shows that this [the raid] was a frame-up and that the real reason [for the raid] was a cash sale” and a “miserable sell-out by the CCL big shots.”[83] For the past year, Herbert Gargrave, a defeated CCF MLA, had been the face of the raid in the smelter city. Now he would be replaced by James “Shakey” Robertson, a former miner from Cumberland, BC, who arrived well equipped to continue with the Red baiting tactic. “He is a turn-coat Communist who has finally seen the light,” wrote Murphy, fresh from a summer of negotiating a collective agreement with the CM&S that set “new standards for Canada” and gave workers a solid wage boost.[84] Whether or not the company believed that Murphy had bested them at the bargaining table is not recorded. However, it “joined the current hysteria of red-baiting and witch-hunting,” Murphy noted of the CM&S attempt to amend BC’s ICA Act to favour the employers, “and proposed that all officers of unions and employees should be compelled to take an oath that they are not communists.”[85]

In early 1952, with McCarthyism in full stride, Murphy contacted his friend Paul Robeson, the famous American singer-activist, and asked him to perform at a Mine-Mill convention in Vancouver in late January. He gladly accepted Murphy’s invitation but when he arrived at the US-Canada border at Blaine, Washington, he learned that the US State Department had seized his passport. Robeson had never said he was a Communist, but he was known for his negative views on American foreign policy and President Harry Truman. That was enough for the US government to confiscate the travel documents of this world-renowned entertainer. Murphy was furious and immediately set about organizing a protest at the US consulate in Vancouver. He then committed his union to sponsoring a series of annual concerts starring Robeson to be held at the Peace Arch near Blaine. It was a spur-of-the-moment action that would at once anger and please CPC leaders for Robeson had long sung the praises of the Soviet Union and aligned himself with Mine-Mill and other unions. CCL leaders, not wanting to give Murphy any credit by assisting the grounded singer, stayed largely on the sidelines as concert planning proceeded. Murphy estimated that the 1952 Peace Arch concert attracted 40,000 visitors, a claim the local press reports disputed. Still the concerts – they ran for three more years – may have helped to slow the attacks on Mine-Mill given how much the Canadian public adored Robeson. But they were not enough to stop the official harassment of the union’s international leaders many of whom faced legal proceedings well into the late 1950s.[86]

Murphy orchestrated four Peace Arch concerts in the 1950s featuring Paul Robeson (UPI-Bettman News).

The raid under Shakey Robertson’s direction continued into 1952, but his credibility dipped when he claimed over Trail radio airwaves that the CPC had ordered him to “join an anti-union drive.” The District News, quoting a CPC press release, noted that Robertson was a “renegade and an unprincipled careerist” who had been expelled from the party for misappropriating union and party funds.[87] By May it was clear that Steel would continue losing their bid to represent Trail’s smelter workers when an LRB decision declared Local 480 was the legal bargaining agent by a vote of 1949 to 1669. It seemed to signal the end of the three-year “vicious, expensive and intensive” disruption, as Murphy described it, but Millard “sneaked into Trail” to announce that it was not over.[88] In fact, it was over and Local 480 turned to other battles such as the protest over Bill H-8, a set of anti-Red and anti-union amendments to the Criminal Code that Murphy argued were “more dangerous than the Taft-Hartley Act, McCarran Act, and other bills designed for the repression of trade unions and progressive thought.”[89]

Peace came to Korea in 1953 and though it had little to do with a BC legislature call to end what historians would call “the forgotten war,” it was a credit to Local 480 charter member Leo Nimsick, CCF MLA for Cranbrook, BC, that he had introduced the call for a cease-fire.[90] That spring, Murphy used his District News column to praise the recently dead Soviet leader Joseph Stalin. Three years later “this cobbler’s son who led a great nation” would be exposed as a monster.[91] Murphy also supported Ethel and Julius Rosenberg, the Americans convicted of spying for the Soviets, by publishing a comment from “famed Italian-American martyr Bartolomeo Vanzetti: “I hope to be the last victim of such a great injustice.”[92] While these comments on controversial events might have have earned some Murphy some kudos, they would also have made some new Cold War enemies. This might also have been true of his comments on the Sons of Freedom Doukhobors, the often-persecuted Russian religious sect that had been transplanted to BC in 1908:

The fact that the Doukhobors are looked upon as being mischief-makers and have been the victims of lurid propaganda that has incited people against them, should not prevent them from having the same treatment as other people, with the full protection of the law.[93]

The Robeson Peace Arch concert drew fewer people that August and mainstream press coverage sent Murphy back to his editorial desk to argue that “there was no ‘heckling’ of Robeson,” as the Vancouver Sun had stated, and that 25,000 attended the event, not the 3,000 the Sun had estimated.[94] In an uplifting event towards the end of the year, Murphy reported that Local 480, upon learning that black Mine-Mill leader Asbury Howard had been refused entry to Canada, had decided that “if Brother Howard could not come to meet the Trail membership, then as many of the Trail members as possible should go and meet him at the border.” About fifty members did exactly that.[95]

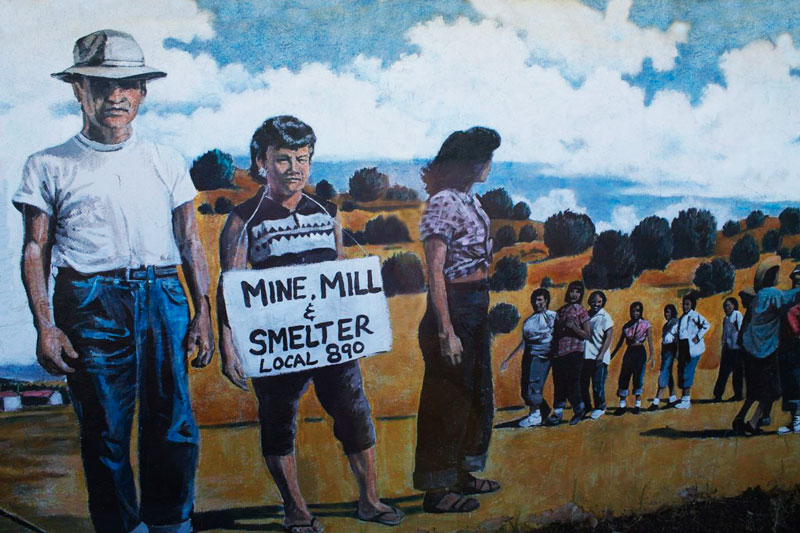

CM&S profits soared to $32 million before taxes, a prompt to Murphy and Local 480 to make demands for higher wages at the bargaining table in spring 1954.[96] But he also faced more trouble on the strike front when a sub-local of Local 651 at the Blue Bell Mine in Riondel, BC, downed tools late that spring. The dispute brought the Trail ladies auxiliary to the fore to provide strike support and to assist Riondel spouses in forming an auxiliary of their own. Murphy’s best columnist Ted Ward, aka “The Tired Mucker,” had become the District News’s chief American critic, managing to blame the US authorities for the Winnipeg Ballet Company’s cancellation of a performance in Mine-Mill-dominated Sudbury, Ontario.[97] By August, Clinton Jencks, the Mine-Mill representative who had worked with Local 890 at a zinc mine and smelter in Bayard, New Mexico, was in jail on account of what turned out to be false testimony by FBI informant Harvey Matusow. He had claimed that Jencks was a Communist who had falsified a Taft-Hartley affidavit swearing that he was not a member of the party. Murphy came to the support of his fellow Mine-Mill representative and Jencks responded with this inspired message from his jail cell:

As I sit here you are busy with the thousand and one final arrangements for the Robeson Peace Arch Concert. And even although the bosses’ steel and concrete will keep me here on August 1, my thoughts and heart will be with the great Canadian people, and that great fighter for all common people everywhere, Paul Robeson.[98]

It was a generous gesture, but at the height of the McCarthy witch-hunts support for Jencks and Robeson was not popular with everyone nor was his promotion of a Mine-Mill-sponsored film that Jencks had helped produce.

Eight months earlier, another voice from New Mexico brought greetings to Mine-Mill locals in BC. Anita Torres, a young Mexican-American trade unionist wanted BC trade unionists to support efforts to free Jencks.[99] She also called on union members to lobby for the showing in BC of the supressed film Salt of the Earth that depicted her Mine-Mill local’s winning struggle against a giant zinc company. Murphy accepted the challenge and began to promote the controversial film that would premiere in only eleven theatres by the end of 1954. In so doing, he created yet another point of attack for his anti-Red detractors. He railed against the suppression of Salt, using his District News to argue that the big theatre chains were “sabotaging it and denying to the movie goers the opportunity” to see it. But it did not diminish the Cold War barriers that had been erected. Indeed, from the moment Salt was conceived by blacklisted Hollywood Ten members director Herbert Biberman, producer Paul Jarrico and screenwriter Michael Wilson, an Oscar winner, the film was a target of anti-Communists from all directions. Even the projectionists union, the International Alliance of Theatrical Stage Employees and Moving Picture Operators (IATSE), barred Salt from most American theatres, thanks to Roy Brewer, the doggedly anti-Communist IATSE representative.[100] Local 480 took the courageous step of screening the film in Castlegar, BC, in mid-December 1954, About 900 viewers attended, but it did little to smooth the waves of anti-Communist propaganda that followed Murphy and Salt.

That summer, Mine-Mill locals in Canada took another step towards independence from the besieged international union, its leaders facing multiple charges under Taft-Hartley and other anti-Communist laws for their left-wing political beliefs. As Al King explained, U.S. Mine-Mill had supported an embargo on importing Canadian zinc while the Canadian locals were naturally opposed to it.[101] The dispute ended in the founding of an autonomous Canadian Mine-Mill central union following a vote at the historic Rossland Miners’ Union Hall constructed by members of Local 38, the first Western Federation of Miners (WFM) local in Canada, at Rossland, BC, in 1898. The District News described the moment:

The members of the Mine, Mill and Smelter Workers Union, those of the present, and the hardy old-timers of the past, were as one in voice and deed and the labor movement of this continent, whose eyes were on Rossland for those days, witnessed events of great importance.[102]

It was vintage Murphy rhetoric that District News readers would soon miss for the paper would not survive his departure for his home town of Toronto to serve as vice-president of the new union where he would become editor in chief of its journal the Mine-Mill Herald. Ironically, he would steer Mine-Mill into the arms of the USWA in 1967, having urged locals to merge with their former enemy. Shipyard union leader Bill White, who sang Murphy’s praises earlier, saw it as a betrayal, claiming that Murphy did it for an extra $500 a month for life.[103] Eventually, the USWA took over most of Canada’s remaining Mine-Mill locals, with the exception of its Falconbridge local in Sudbury, Ontario. In the end, the larger union won out over those at Local 480 who had fought so hard to avoid it during the raiding years of the 1950s.The merger meant Murphy joined the staff of his old adversary, Steel, and he worked there from 1967 until he retired. Within a few years the BC legacy of one of Canada’s most flamboyant Red agitators began to disappear.

***

It seems strange that Murphy, who was for a decade a major player in BC’s labour movement, could be so easily dismissed. Perhaps it was fear that led the movement’s elected leaders to shun him. Perhaps they were driven to ostracize him for his unabashed and highly public criticisms of their leadership. Perhaps they were afraid that the anti-Red and anti-union hysteria promoted in the media throughout much of the first half of the 20th century would taint them as well. Then again, maybe they were jealous of Murphy’s accomplishments in unionizing BC’s growing mining and smelting industry. Clearly, the leaders of the CCL and the rival TLC were not alone in their antipathy to a man who was for a time BC’s premier Red agitator. Politicians, government officials, and the media for which he generated so many sensational headlines, supported anyone who was anti-Murphy. Even the CPC seemed to distance itself from him.

Al King worked closely with Murphy when he served as Local 480 president in the 1950s. Courtesy USW Local 480.

Without doubt, Murphy made a significant contribution to the BC labour movement and to the continuing fight for social justice, but not everyone would agree that his life and times are worth revisiting. Al King thought Murphy was “a very clever, accomplished” trade unionist, but added that he was a “cagey operator” who “could also on occasion be an unscrupulous bastard.” From King’s perspective as someone who worked closely with him, “you either loved Harvey Murphy or you hated him.”[104] “Mine Mill was not without its own flaws,” historian Bryan Palmer wrote in a paper prepared for a 1993 conference to commemorate the first 100 years of Mine-Mill history. “On the west coast, its problems often seemed wrapped up in the authoritarian arrogance of the union’s major figure, Harvey Murphy.”[105] Certainly, many in the USWA’s leadership ranks would agree. Former USWA international president Lynn Williams barely mentions Murphy in his 2011 memoir, One Day Longer, and in an interview with the author he scoffed at Murphy’s bargaining style saying that he was too quick to jump on board with employers. Even the CPC did not find Murphy worthy of much space in an official history published in 1976, a year before Murphy’s death. He merits an appearance in two group photographs and garners cursory mentions in which the party acknowledges him as “a prominent union organizer in both the WUL and the CIO and a leader of the struggles of the unemployed in Ontario in the last half of the thirties.”[106] It further notes that he was a member of the Friends of the Mac-Paps, the volunteers, many of them BC Communists, who fought in the Spanish Civil War. It also includes a note on one of his crowning achievements, the four Paul Robeson Peace Arch concerts.

Five years after his retirement, the RCMP continued to report on his activities. His “Consolidated Personal History File” for 1972 corrected some of the inaccuracies that were recorded decades before. These included his various home addresses, the type of car he drove, the full maiden name of his wife Isobel along with her parents names, the full names of his three children, and his physical description: height – 5 feet, 8 inches; weight – 200 pounds; build – “stout, erect”; complexion – “dark,” eyes “blue, small”; hair – “Bald – fringe on side”; straight nose, clean shaven, ears – “close to head.” It was all noted, even his attendance at a hockey game between the world amateur champion Trail Smoke Eaters and the Soviet Moscow Selects at the Trail Memorial Arena in 1960. The dutifully recorded his trip to Moscow in 1971, and the view that CPC general secretary William Kashtan and other CPC leaders “do not trust him.” [107] In a statement that probably amused Murphy, the old battler who had so often sparred with his spies, the police suggested that “in view of this and his advanced age, we do not consider him a threat to our national security.”[108]

Murphy died on 30 April 1977 at age 72. A telegram marked secret was sent to “Area Security Service “D” Ops (Pro-Soviet) in Toronto indicating the date of death.[109] It also noted that, “Murphy was reported by Queensway Hospital in Etobicoke, Toronto, to have been dead on arrival. Death certificate #77-05-0198586 was issued. The telegram added that, “As this file has historical value, could it please be retained,” and with that curt request it joined the thousands of bits and pieces of Murphy’s life that could now be stamped “Dead File.”[110] Sadly, Murphy died unwanted by the movement he had served, remembered his eldest son Rae who had followed his father into the CPC, serving as editor of the CPC’s Canadian Tribune. He recalled how labour leaders of the day politely refused the once captivating union orator’s offers to speak at rallies and on picket lines after he retired.[111] He died friendless except for a few of the old Crow’s Nest Pass miners who remembered and admired the man that 1934 police report called “a little ‘God’ among the Reds.”[112]

Clearly, he was among a handful of radical Red firebrands that helped shape union politics in BC. Among his BC contemporaries were fellow Communists like Arthur “Slim” Evans, Jack Scott, Harold Pritchett, Maurice Rush, and Jack Kavanagh. Joining them as shapers in a different sense were many socialists and labour-friendly politicians like Tom Uphill, Leo Nimsick, and Bert Herridge. Much has been written about many of these men, comparatively much less on Murphy.[113] Perhaps this is due to a lack of biographical data; Murphy himself left few clues in the archives. Also, sociologist Rolf Knight had intentions of writing a biography, and to that end he interviewed Murphy a year before his death in April 1977. He concluded that Murphy’ memory was impaired possibly by a series of minor strokes. He abandoned the project.[114] Even so, Murphy’s long tenure as a party stalwart, peripatetic labour spokesman, occasional electoral candidate, and workers’ friend would seem to merit more attention.

His friend and fellow Communist union leader Ray Stevenson agreed when in a Canadian Tribune tribute to the memory of Murphy he called him “a man for and of the storm.” It might have been a suitable epitaph for this street-taught, street-tough Marxist trade unionist who had dedicated his life to the service of working people. Appropriately, he is buried in the town that was once called “Red Blairmore” where, as Stevenson further noted, “he wrote stirring pages into the history of the province” of Alberta. He might have added that he did the same for the labour movement of BC.[115]

[1] Stephen L. Endicott, Raising the Workers’ Flag: The Workers’ Unity League of Canada, 1930-1936 (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2012), 126, mentions the phrase but does not source it.

[2] Allen Seager, “Harvey Murphy,” The Canadian Encyclopedia, Historica-Dominion Institute, Toronto, 2011, http://www.encyclopediecanadienne.ca/articles/harvey-murphy.

[3] Peter S. Mclnnis, “Big Lives: Recent Publications in Canadian Labour Biography,” Labour/ Le Travail, 45 (Spring 2000), 276.

[4] Tom McEwen, the CPC’s Pacific Tribune editor, for example, admonished him for his failure to report on his organizing activities in a timely manner, pleading with him to “for Christ sake come down to earth.” Murphy from McEwen, 19 December 1929, found in the transcript of an interview conducted by a Defence of Canada Regulations advisory committee, Toronto, 1 December 1941, 41. The committee was seeking any evidence that would allow it to send Murphy to an interment camp. Criticism from fellow Communists was helpful.

[5] Endicott, 122, notes that in the aftermath of the 1932 Crow’s Nest Pass strike, for example, he was upbraided for being “a bureaucrat – in effect a dictator– and a factionalist.”

[6] Lita-Rose Betcherman, The Little Band: The Clashes between the Communists and the Canadian Establishment 1928-1932 (Ottawa: Deneau Publishers, 1982); Stephen L. Endicott, Raising the Workers’ Flag (see full reference above).

[7] RCMP Commissioner Cortlandt Starnes to A.L. Joliffe, Commissioner of Customs, Department of Immigration and Colonization, Ottawa, 30 April 1930.

[8] Malcolm Bruce, “Wilde Harvie’s Pilgrimage,” typed manuscript, Rare Books and Special Collections, UBC Library, Vancouver, BC.

[9] Mercedes Steedman, Peter Suschnigg and Dieter K. Buse, eds, Hard Lessons: The Mine Mill Union in the Canadian Labour Movement (Toronto: Dundurn Press/Institute of Northern Ontario Research and Development, 1995), 46.

[10] John Stanton, My Past Is Now: Further Memoirs of a Labour Lawyer (St. John’s, NL: Canadian Committee on Labour History, 1994), 119.

[11] Doug Smith, Cold Warrior: C.S. Jackson and the United Electrical Workers (St. John’s, NL: Canadian Committee on Labour History, 1997), 219.

[12] Maurice Rush, We Have a Glowing Dream: Recollections of Working-Class and People’s Struggles in B.C., 1935-1995 (Vancouver: Centre for Socialist Education, 1996), 162.

[13] Gerald Tulchinsky, Joe Salsberg: A Life of Commitment (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2013), 93.

[14] Murphy’s eldest son Rae Murphy, interview with the author, Mississauga, Ontario, 18 November 2007; also see Hoffman, 1, for surname verification.

[15] Several interviews provide family background. See Rolf Knight, Rolf Knight Papers, Harvey Murphy transcripts (file 8-2), UBC Main Library, Rare Books and Special Collections, Vancouver, BC, the most extensive of the interviews. Also useful are interviews by Alice M. Hoffman, Islington, Ontario, 31 March 1976 (author’s copy); David Millar, Toronto, 24 September 1969, Millar fonds (MG31-B6, Volume 1), Public Archives of Canada, Ottawa, Ontario; Allen Seager, Toronto, 22 September 1976 (author’s copy).

[16] Besides Buhay and possibly her brother Michael, Murphy’s early Red heroes included Maurice Spector, editor of the CPC’s The Worker, John “Red Jack” or “Moscow Jack” MacDonald, an early leader of the CPC, James “Big Jim” McLachlan, the Communist leader of Nova Scotia’s miners, Malcolm Bruce, and Tom McEwen.

[17] Maryann Murphy, a short biographical paper attached to the Knight transcription, 6. Maryann, Murphy’s daughter, was then a student of sociologist Rolf Knight’s at the University of Toronto.

[18] No author, “Personal History File,” 7 December 1929, 1, obtained from Canadian Security and Intelligence Service files through Access to Information legislation as are other such reports referenced in this article.

[19] Personal History File for Harvey Murphy, BC Provincial Police, Prince Rupert, BC, 3 April 1933, BC Archives GR-0429 (Box 21, File 6, Folio 321).

[20] Allen Seager, “A History of the Mine Workers’ Union of Canada, 1925-1936,” MA Thesis, McGill University, 1977, offers an account of the Anyox strike.

[21] Seager, MWUC history, 210-211.

[22] Dorothy Livesay, Right Hand Left Hand: A True Life of the Thirties (Erin, ON: Press Porcepic Ltd., 1977), 206.

[23] Interview transcript, Defence of Canada Regulations advisory committee, 61, noted the figure, which Murphy denied.

[24] Knight, 102-104, provides Murphy’s account of events during the Pioneer strike.

[25] “Strike at Pioneer Gold Mines Illegal,” Secret Intelligence Bulletin, Weekly Summary, RCMP Headquarters, Ottawa, 13 November 1939.

[26] Commentator, 13 November 1939.

[27] Commentator, 13 November 1939.

[28] Knight, 91. The arrest occurred on 4 November 1941. See also “Information Bulletin,” National Council of Democratic Rights, Toronto, 5 November 1941.

[29] Reginald Whitaker, “Official Repression of Communism During World War II,” Labour/Le Travail, 17 (Spring 1986): 145-146, 138, describes the repressive powers of the DOCR in detail.

[30] J.A. “Pat” Sullivan, “Pat Sullivan’s Inside Story of Communist Infiltration,” Toronto Telegram, 4 April 1955. This was the first in a series of articles written by the former Canadian Seaman’s Union president. See also Pat Sullivan, Red Sails on the Great Lakes (Toronto: Macmillan, 1955) and William Kaplan, Everything that Floats: Pat Sullivan, Hal Banks, and the Seamen’s Unions of Canada (Toronto, University of Toronto Press, 1987).

[31] Knight, 93.

[32] Knight, 96.

[33] Interview transcript, Reid Robinson, Chase Powers and Tom McGuire, interview conducted by Ron Filippelli, San Francisco, 12 December 1969, available at Pennsylvania State University Archives.

[34] Knight, 98.

[35] Laurel Sefton MacDowell, ‘Remember Kirkland Lake’: The Gold Miners’ Strike of 1941-42 (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1983) and other historians view the strike as a key reason why Prime Minister Mackenzie King introduced Order-in-Council PC 1003, giving unions legal bargaining rights in February 1944.

[36] Elsie G. Turnbull, Trail Between Two Wars: The Story of a Smelter City (Victoria, BC: Morriss Printing Co., 1980), 85.

[37] David Michael Roth, “A Union on the Hill: The International Union of Mine, Mill and Smelter Workers and the Organization of Trail Smelter and Chemical Workers, 1938-1945,” MA thesis, SFU, 1991, 62.

[38] BC District Union News (hereafter District News), 10 June 1945, claimed that the paper had a circulation of 6,200 readers.

[39] His articles had appeared in The Worker, an early Communist newspaper and later The Clarion. In addition, he had founded several regional publications to cater to the interests of unemployed workers and miners.

[40] District News, 28 June 1944, provides details of a tentative agreement following Local 480’s certification on 2 June 1944.

[41] District News, 25 January 1945.

[42] District News, 25 January 1945.

[43] District News, 25 May 1945.

[44] District News, 10 June 1945. Note that the date of the edition, 10 June, must be erroneous.

[45] Dorise Neilson, who in 1943 became the first CPC member to be elected to federal office, also ran for re-election and might have been a second reason why the election was important, but like Murphy she lost.

[46] District News, 20 May 1946.

[47] District News, 24 June 1946.

[48] District News, 20 May 1946.

[49] District News, 6 May 1946.

[50] Trail Daily Times (hereafter TDT), 16 January 1947; Saturday Evening Post, 18 January 1947.

[51] District News, 14 April 1947.

[52] Laurie Mercier, “‘A Union Without Women is Only Half Organized’: Mine Mill Women’s Auxiliaries, and Cold War Politics in the North American Wests,” in Elizabeth Jameson and Sheila McManus, eds., One Step Over the Line: Towards a History of Women in the North American Wests (Edmonton: Athabasca University Press/University of Alberta Press, 2008), discusses the Orlich affair in detail.

[53] Martin Robin, Pillars of Profit: The Company Province 1934-1972 (Toronto: McClelland and Steward, 1973), 98, discusses Bill 39 and a follow-up in 1948, Bill 87, neither of which met with union approval.

[54] District News, 28 August 1947.

[55] District News, 4 August 1947.

[56] Jack Scott, A Communist Life: Jack Scott and the Canadian Workers Movement, 1927-1985, Bryan D. Palmer, ed. (St. John’s, NL: Committee on Canadian Labour History, 1988), 84.

[57] TDT, 26 July 1947, 1; TDT, 24 July 1947.

[58] District News, 30 April 1947.

[59] King, Red Bait!, 71.

[60] King, Red Bait!,76.

[61] TDT, 14 April 1948.

[62] Howard White, A Hard Man to Beat: The Story of Bill White, Labour Leader, Historian, Shipyard Worker, Raconteur: An Oral History (Vancouver: Pulp Press, c1983), 168.

[63] TDT, 10 February 1949.

[64] John Stanton, My Past Is Now: Further Memoirs of a Labour Lawyer (St. John’s, NL: Canadian Committee on Labour History, 1994), 119.

[65] Bruce Mickleburgh, “Consolidated Prepares an Inside Job,” Pacific Tribune, 11 March 1949; and, “The War Scare Pays off – For Consolidated,” PT, 18 March 1949.

[66] District News, 27 June 1949.

[67] Alfred Sowden, District News, 17 May 1949.

[68] District News, 17 May 1949.

[69] District News, 27 June 1949.

[70] District News, 31 August 1949.

[71] District News, 28 November 1949.

[72] Rae Murphy (deceased), interview with the author, Mississauga, Ont., 1 November 2010.

[73] TDT, 21 February 1950.

[74] Mine-Mill Union, 5 June 1950.

[75] District News, 17 April 1950.

[76] District News, 17 April 1950.

[77] TDT, 13 November 1950, 4.

[78] District News, 11 July 1950.

[79] District News, 30 March 1951.

[80] Pierre Berton, “How a Red Union Bosses Atom Workers at Trail, B.C.,” MacLean’s, 1 April 1951, 7-10, 57.

[81] District News, 30 April 1951. For a detailed history of Trail’s heavy water plant, see BC Studies, No. 186, Summer 2015, 95-124.

[82] A.B. McKillop, Pierre Berton: A Biography (Toronto, McClelland & Stewart, 2008), 258-259.

[83] District News, 28 September 1951.

[84] District News, 31 October 1951; District News, 13 July 1951.

[85] District News, 28 September 1951.

[86] See BC Studies, No. 174, Summer 2012, 61-99, for a detailed account of the concerts.

[87] District News, 4 January 1952.

[88] District News, 6 June 1952.

[89] District News, 20 November 1952.

[90] District News, 23 February 1953. See John Melady, Korea: Canada’s Forgotten War (Toronto: Dundurn, 2011).

[91] District News, 24 March 1953.

[92] District News, 24 March 1953.

[93] District News, 25 September 1953.

[94] District News, 18 August 1953.

[95] District News, 23 October 1953.

[96] District News, 31 March 1954.

[97] District News, 30 April 1954.

[98] District News, 31 August 1954.

[99] District News, 29 January 1954.

[100] See Labour/Le Travail, Fall 2015, 165-198, for a detailed account of the Mine-Mill-sponsored film.

[101] King, Red Bait!, 12126-127.

[102] District News, July 1955. The WFM changed its name to Mine-Mill in 1916.

[103] White, 248.

[104] King, Red Bait!, 57.

[105] Steedman et al, 46.

[106] Canada’s Party of Socialism, 127.

[107] “Personal History File,” RCMP “D” Branch, 1 June 1972.

[108] “Information” and “Investigator’s Comments,” name redacted, Toronto Security Service “O” Division, 1 June 1972.

[109] Murphy cited contradictory birthdates in various interviews. The most persistent date on record seems to be 1905. Hoffman, 1. Buck, Thirty Years, states that it was 1906. He adds the Murphy was twenty-two when he led the 1928 National Steel Car plant strike Hamilton “like a veteran,” https://www.marxists.org/history/international/comintern/sections/canada/buck-tim/30years/ch02.htm .

[110] Telegram X7007 1573, Toronto “D” Ops, Southwestern Ontario Security Service, 14 April 1978.

[111] Rae Murphy, interview with author.

[112] Sergeant J.A Cawsey, Blairmore, Alberta, RCMP Detachment, in secret report dated 20 November 1934.

[113] James Naylor, The Fate of Labour Socialism: The Cooperative Commonwealth Federation and the Dream of a Working-Class Future (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2016) and Peter Campbell, Canadian Marxists and the Search for a Third Way (Montreal/Kingston: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 1999) offer thoughts on early socialists in the CCF and the CPC.

[114] See Knight interview introductory memorandum for a more detailed explanation. See also Rolf Knight, “Harvey Murphy: Reminiscences 1918-1943,” 1976, http://rolfknight.ca/HARVEY-MURPHY.pdf.

[115] John Weir, Canadian Tribune, 12 April 1982.

**

Ron Verzuh is a Canadian writer, historian, photographer, and documentary filmmaker who is currently completing his doctoral dissertation in history at Simon Fraser University. He is a retired national communications director for the Canadian Union of Public Employees and author of three books, several monographs and numerous articles on subjects ranging from trade unionism and politics to travel, literature, news media, film, and food. Verzuh currently lives in Eugene, Oregon. Verzuh is also a former Oregon vice-president of the Pacific Northwest Labor History Association. His particular field of study has been the labour and social relations that engulfed Trail, B.C., from 1935 to 1955.

Leave a Reply