#141 Retrieving Noel from obscurity

June 21st, 2017

REVIEW: Abenaki Daring: The Life and Writings of Noel Annance, 1792-1869

by Jean Barman

Montreal and Kingston: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 2016.

$35.96 / 9780773547926

Reviewed by Michel Bouchard

*

Noel Annance was an “Abenaki gentleman” whose trans-continental travels gave rise to the name for Annacis Island.

“His seeking to pass literacy’s promise on to the next generation in his home community so they might dare literacy’s promise in their lives, as he had done, came to naught.”– Jean Barman

*

Too often, scholars must do their best to distill the thoughts and narratives of the destitute, downtrodden, or the illiterate through the written accounts of those wielding power and privilege. Jean Barman, however, provides a telling account of the life of one man, Noel Annance (1792-1869), an Abenaki gentleman who was not only literate but left behind a rich assortment of documents from his own hand ranging from reports and letters to love notes.

In the process, Barman provides a comprehensive account of the lived experience of an Indigenous man in a society where an increasingly paternalistic state structure imposed itself on the daily lives of Indigenous peoples. In Abenaki Daring: The Life and Writings of Noel Annance 1792-1862, Barman recounts the history of the fur trade in the Canadian west and north in the early nineteenth century and the origins of the eventual “Indian Act” in pre-Confederation Canada by a close reading of the abundant documentary trail left behind by Annance.

Annance’s life and that of his parents and grandparents straddled the Conquest of New France, the American Revolution, the War of 1812, the Union of the two Canadas, and finally Canadian Confederation. Within this span, the Abenaki were transformed from essential allies of New France fighting the English in the Continental colonies – indeed, two of Annance’s great-grandparents had been taken prisoner and fully adopted and integrated into Abenaki society — to British allies against the new American Republic.

Annance’s life, as for the Abenaki generally, was one of great change, as Barman notes. “At his birth, they were still perceived as having utility; by the time of his death, they had been cast aside” (p. 3). Abenaki Daring provides a much-needed account of a pivotal time in Abenaki – and Canadian – history as told through the exceptional writings of this early Indigenous author.

The great-grandchild of captives taken from the English colonies and raised by the Abenaki, allies of New France, Annance was born in St. Francis (Saint-François-du-Lac), Lower Canada. As a young man he was sent to Dartmouth College in New Hampshire where it was thought his “white” ancestry would give him a better chance of success, and where he was turned out as an educated and literate gentleman. Nevertheless, Barman concludes, he was still too “Indian” both for advancement in the fur trade and for the settlers of nineteenth century Canada.

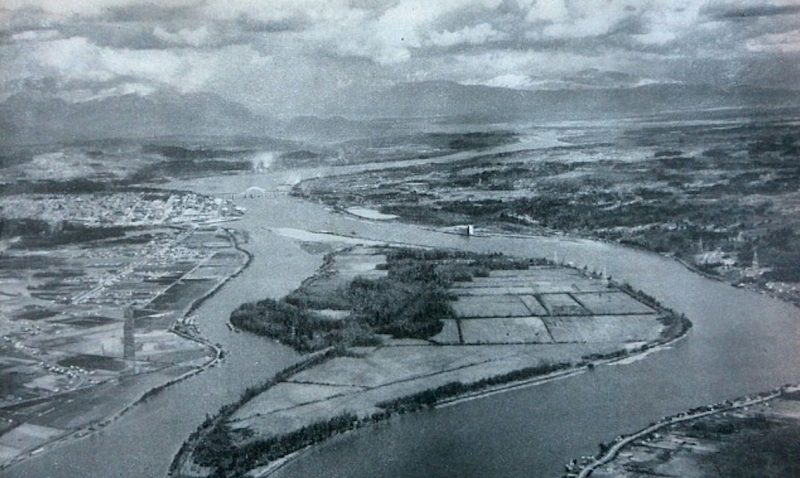

Barman traces Annance’s life not only through time, but also across the continent. He signed up with the North West Company (NWC) in 1818 and, after the fusion of the NWC with the Hudson’s Bay Company (HBC), continued as a clerk. He was stationed on the Pacific coast from 1824-1833 while working for the HBC; helped choose the site of Fort Langley, where he worked as an HBC officer; and gave his name (in a corrupted form) to Annacis Island in the south arm of the Fraser River at what is now Delta.

Annance was not the only Abenaki to have ventured this far west, but Annance provided a substantive written legacy that permits Barman’s captivating telling of his transcontinental story.

Barman builds upon two primary sources discovered by the fur trade scholar Morag Maclachlan: an 1824 manuscript journal from his reconnaissance of the lower Fraser River, which resulted in the establishment of Fort Langley three years later, and some “love notes” that Annance penned a decade later while working for the HBC.

Altogether, Annance left behind a trove of letters and other documents that provide a detailed first-hand account of a life from an Indigenous perspective in the early nineteenth century.

The documents provide a decades-long account of Annance’s lifelong challenge to be respected as a gentleman, a title that his rich education should have afforded him, while remaining true to this Abenaki identity. As Barman writes: “Noel Annance was one of the tiny number of Indigenous peoples across North America with the means to speak back to the dominant society on its own terms” (p. 7).

Barman asserts that Annance’s life provides a telling account of the structural forces that would crush the aspirations of even the most ambitious Indigenous risk-takers, even those with European ancestry and advanced education. Barman provides a compelling and personal history of Annance’s life from his prestigious future ivy-league college, to his role as a British officer in the War of 1812, to his journey to the North West and Pacific coast with the NWC and HBC, to his career in the thriving fur trade, and finally back to his home community where he lobbied tirelessly to ensure that his rights and those of his Abenaki kin would not be forsaken.

However, being a gentleman who could cite classic Greek and Latin texts was not sufficient. He was pushed aside in the fur trade outposts, and later in his life he was continually passed over in his desire to become a teacher in his community. He faced candidates who had none of his qualifications yet benefited from not being Indigenous. Barman’s account thus exposes decades of structural inequalities even prior to the 1876 Indian Act, which stood in the way of exceptional Indigenous individuals who dared to seek to integrate and ingratiate themselves into the increasingly dominant settler society.

Abenaki traditional territory covered what is now northern New England and southern Québec. As allies of the French, the Abenaki were granted a concession of land reserving for their use the St. Francis (Saint-François) Mission located at the mouth of the Saint-François river were it meets the St. Lawrence. Between the French and English, and later the British and American, forces the Abenaki did their best to survive the turbulent years before the conquest of New France and its transfer to British sovereignty with the Treaty of Paris in 1763.

Abenaki traditional territory covered what is now northern New England and southern Québec. As allies of the French, the Abenaki were granted a concession of land reserving for their use the St. Francis (Saint-François) Mission located at the mouth of the Saint-François river were it meets the St. Lawrence. Between the French and English, and later the British and American, forces the Abenaki did their best to survive the turbulent years before the conquest of New France and its transfer to British sovereignty with the Treaty of Paris in 1763.

While French and English (British) battled, the Abenaki had taken a number of captives. Though most were eventually released and returned to their home communities, some did stay and become “white Indians.” As Barman notes, at most 52 of the captured New England prisoners integrated fully into their new Indigenous communities, and 38 of these had been children and adolescents under the age of sixteen. Two of Noel Annance’s ancestors, Samuel Gill and Rosalie James, had been among these 38 captives (p. 23).

The Abenaki at St. Francis were decimated in October 1759 by the Rogers’s Rangers, a company of the British militia, which attacked the town, killed some 200 Abenaki, and burnt most of the houses to the ground. The Abenaki population, which had numbered some 1,000, was reduced to 400 in the war.

Having barely survived earlier colonial wars, but still hoping to maintain their lands, the Abenaki were forced to play the British and the colonial Americans against each other as the thirteen continental British colonies sought their independence.

One of Annance’s great-uncles, Joseph-Louis Gill, first sided with the Americans, being given the rank of major in the continental army, then changed sides when it became clear that the British would hold onto the lands of St. Francis (p. 36). Seventeen Abenaki heads of household — all descendants of the two New England captives – were granted 8,900 acres in 1805 for the services they had rendered to the British during the war. One of them was Francis Joseph Annance, Noel’s father.

Born at the end of a turbulent century, Noel Annance would be raised with stories of captivity as well as the knowledge that lands had been granted in Durham Township. The other family legacy, which Noel received, was his education at Dartmouth College.

Dartmouth had begun as Moor’s Indian Charity School to train First Nations children to be missionaries. Following fundraising in Scotland, England, and in the colonies, a charter for the school was granted in 1769 and Moor’s was renamed Dartmouth. It began to train local settler children and thus became the tenth oldest North America’s postsecondary institution (p. 43).

Noel Annance’s father attended Moor’s and then Dartmouth, completing three years before returning home to Canada as conflict grew prior to the American Revolution. In 1808, following his older brother Louis, Noel also went to Moor’s and in 1810 was admitted to Dartmouth College (pp. 55-62).

Barman notes that Noel was “among a very small number of Indigenous persons across North America, earlier in time or in his generation, given the opportunity to access literacy’s promise” (p. 67). However, he was taught more than to read; he was taught to be a gentleman, one of the elite. He stayed until 1813, when the War of 1812 was beginning to truly rage. From there he would join the British forces.

During the War of 1812, Noel Annance served as an interpreter and was quickly promoted to Lieutenant. This would be the last continental war in which First Nations would serve as allies. Annance distinguished himself in the Battle of Chateauguay and, as a decorated war veteran, was promoted to captain the next year (pp. 82-84). Having achieved the rank of military officer and gentleman, Annance expected to rise in society and to this end he entered the NWC’s Montreal-based commercial empire as a clerk.

The NWC, and then the HBC, should have provided certain advantages to Annance not available in the British settler colonies. Citing John Milloy, Barman asserts that the British “colonies had no natural place for the Indian, no inclination to mix the blood of the races, no need for Indian labour and no undeniable compulsion to civilize him” (p. 91). However, as Barman notes, “Noel may not initially have fully realized that the trappings of a gentleman did not, if one was perceived as Indigenous, a gentleman make” (p. 63). Though Annance strove for inclusion in the HBC after 1821, in fact he was excluded — if not actively then certainly passively.

The hierarchical HBC was truly the forerunner of Canada’s vertical mosaic. At the top were the London shareholders to which none of the employees could ever aspire. At the top of the North America apex was governor Sir George Simpson, below whom were the chief factors, chief traders, and clerks, who were almost exclusively Scottish with some Irish and English mixed in. All had to be capable of writing in English since maintaining the fort journals and business correspondence was the task of this company officer elite.

Below them, HBC employees comprised of the [French-] Canadians, the “country born” or “English half-breeds,” and below them the Métis or “French half-breeds,” and farther down were the Indigenous peoples. Thus Annance did not fit easily into the established racial hierarchy. Unlike the Canadians and the “half-breeds” he was an educated and literate gentleman, but he was still an outsider.

Though George Simpson seems to have appreciated Annance at the outset, for unknown reasons he turned against the clerk. By the winter of 1831-1832, Simpson described him in his private “Character Book:”

Annance, F.N. About 40 Years of Age. 13 Years in the Service. A half breed of the Abiniki Tribe near Quebec; well Educated & has been a Schoolmaster. Is firm with Indians, speaks several of their Languages, walks well, is a good Shot and qualified to lead the life of an Indian whose disposition he possesses to a great degree. Is not worthy of belief even upon Oath and altogether a bad character altho’ a useful Man. Can have no prospects of advancement (p. 116).

Annance certainly fell victim to the race consciousness which entrenched itself in the HBC in the 1820s under Simpson, when any Indigenous ancestry disqualified any clerk from upward mobility. His career stalled. While his peers rose up in the ranks, earning more money and receiving shares in the company, Annance remained a clerk and by all accounts became embittered.

Frustrated that his potential was stifled by the rigidity of the HBC hierarchy, Annance had a liaison with the “country wife” of the much older John Stuart when both were stationed at Fort Simpson on the Mackenzie River. It is here that Annance wrote a series of “love notes” preserved by Stuart.

Though Annance had had a country wife, a Flathead woman, they had parted ways before his arrival in Fort Simpson. There, if his notes are a true indicator of his emotions, he was smitten by Stuart’s country wife, Mary Taylor. Though Stuart outranked Annance, Annance outclassed him in education. Annance could speak Greek and Latin, while Stuart could not even distinguish these from “Abonakee” (p. 130). The younger and more refined Annance outshone the older, less refined — but Scottish — Stuart.

The affair however came to a head when Mary Taylor turned over to Stuart all the notes that Annance had proffered her. The final note ended with these words: “I shall always remember with sorrow and tears those places which saw us once happy. Farewell, may you enjoy that happiness which you have refused me” (p. 143).

The relationship made public, Annance as a gentleman apologized to Stuart. The latter wrote to George Simpson who, however, disliked Stuart perhaps even more than Annance and informed Stuart on July 4, 1834 that his “private or family broils” were of no concern to him or the company. Similarly, the following month, Chief Factor John Hargrave characterized the events that had transpired at Fort Simpson as “the acts of two worthless & degraded fools” (p. 147).

By the end of 1834, Annance had left the HBC and was back in St. Francis living as an Abenaki person.

At St. Francis until his death in 1869, Noel Annance witnessed the rise of the bureaucracy which would (mis-)manage the lives of Indigenous peoples. His letters from these years testify to the growing power of the state and the conflict that divided the Abenaki community as well from within. For decades he carried on a correspondence with the Department of Indian Affairs. He even sought to be enfranchised to be finally rid of the legal “Indian status” of a “minor,” and to sever his dependence on the Indian Agent, by which all the Indigenous peoples were weighed down. He was unsuccessful, and the growing bureaucracy of dependence culminated in the eventual Indian Act of 1876.

In an era where race increasingly could not be escaped, the descendants of Samuel Gill and Rosalie James splintered. One part of the family became “white,” which is to say they became the “[French-]canadian part of the tribe” (p. 173). They were French-speaking and Catholic, fully integrated into the surrounding [French-]Canadian society. However, they were more than willing to exploit traditional Abenaki resources, notably the woodlots, to their advantage.

However, tensions also divided Noel Annance and other cousins such as Peter Paul Osunkhirhine, author of Metaphysical Inquiry Deducing many Self-evident Truths from the Very Nature of Things of what God’s Nature and Will Require (Montreal: 1857). Annance effectively sought to relocate Peter from the small school where he was teaching and receiving a missionary stipend to the distant Northwest, thus leaving Noel free to take over the position he vacated. Hearing of this, Osunkhirhine sent a letter in turn to his sponsors in Boston charging that Annance was “unfortunately a man of no religion” (p. 172).

Annance then sought out financial opportunities, such as proposing a translation of Biblical texts into the Abenaki language. He also unsuccessfully vied for years to be the teacher in newly established government schools. However, much as had been the case when he was an HBC employee, his advancement was frustrated and his aspirations blocked by structural forces beyond his control. Thus, the village priest recommended teachers who were less qualified and who, to Annance’s dismay, were hired instead of him.

Noel Annance’s story provides a telling account of the growing power of the Department of Indian Affairs and the legislation that would lead to the Indian Act. Already, prior to Confederation, legislation was being passed to set up reserves, define Indian status, and set forward legislation to “civilize” the two Canadian colonies. Thus, Annance not only bore witness to the emergence of a racialized social hierarchy in the fur trade, but also to the growing power of the nascent Canada over Indigenous individuals. From the 1830s onwards, First Nations individuals were caught in a bureaucratic web in which any power they had over their lives and communities would be eroded.

In this climate, Annance would bear the frustration of not being able to teach and shape the next generation. As Barman writes: “His seeking to pass literacy’s promise on to the next generation in his home community so they might dare literacy’s promise in their lives, as he had done, came to naught” (p. 197). Canada’s First Nations communities have been living the consequences of this for over 150 years.

In Abenaki Daring, Barman provides a thorough and vivid picture of one individual and one family whose travails provide an insightful look into Canada’s forgotten nineteenth history. While no painting or photograph of Annance is known to exist, his life can be assembled with clarity through the documentary record he left behind. As Barman shows, his career testifies to the structural forces that ensured the marginalization and thwarted the career of a gifted and educated First Nations man who had shown exceptional promise.

If the dreams of Noel Annance were crushed, it should come to no surprise that the weight of systemic social forces could bear down on larger communities, thus ensuring their marginalization for generations. Annance’s “Abenaki daring” was sadly no match for the unsparing bureaucratic colonial regime which sought to regulate the “Indians” until, as successive generations of European and Canadian legislators expected, they were no more.

*

Dr. Michel Bouchard is Professor of Anthropology at the University of Northern British Columbia. His research has examined issues of identity and ethnicity both past (medieval Russia and Europe) and present (North America, Estonia, and Russia). He has explored the origins of the word “nation” in Western Europe and the equivalent word in Russian, examined how nationhood was tied to religion in Europe, and challenged assumptions that nations are modern. Closer to home, he has researched the buried history of the Canadien, Métis and other French-speakers who ventured and settled across the continent and challenged national narratives that marginalize the history of French-speakers on both sides of the 49th parallel.

With Robert Foxcurran and Sébastien Malette, he co-authored Songs Upon the Rivers: The Buried History of the French-Speaking Canadiens and Métis from the Great Lakes and the Mississippi across to the Pacific (Baraka Books, 2016).

*

The Ormsby Review. More Readers. More Reviews. More Often.

Reviews Editor: Richard Mackie

Reviews Publisher: Alan Twigg

The Ormsby Review is hosted by Simon Fraser University. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Robin Fisher, Cole Harris, Wade Davis, Hugh Johnston, Patricia Roy, David Stouck, and Graeme Wynn.

—

BC BookWorld

ABCBookWorld

BCBookLook

BC BookAwards

The Literary Map of B.C.

The Ormsby Review

Leave a Reply