#101 The story of a suitcase

March 08th, 2017

From the cryptic contents of a stray suitcase that he inherited from a distant relative, Graham Brazier of Denman Island resurrects the otherwise forgotten personal history of Annie Watson (née Edwards, 1883-1966). It’s a peculiar but moving story we are bringing to light in order to mark International Women’s Day.

Annie arrived in Winnipeg in 1910 and settled in Vancouver a few years later as one of a flood of Edwardian immigrants to Canada. In between the accidental deaths of her brother, her husband, and finally her son, Brazier gives a light-hearted account of Annie’s unexpected return to England in 1949-50 to take a new job as “mayoress of the bustling fishing town of Grimsby.”

This odd elevation to an official governmental position in England only occurred because her sister’s husband was either disallowed or disinclined to accept a position that was socially inferior to that of his wife.

“My hope was to recapture the flavour of the time which, from this distance, appears both harmlessly frivolous and innocent,” Brazier notes in an email. – Ed.

*

by Graham Brazier

A suitcase came unexpectedly into my possession some years ago. Everything about it was curious, from its arrival to its appearance and disorderly contents. Eventually I was able to trace its path from one basement to another, and from one distant relative to another, until it ended up in my mother’s basement in Central Saanich, on Vancouver Island.

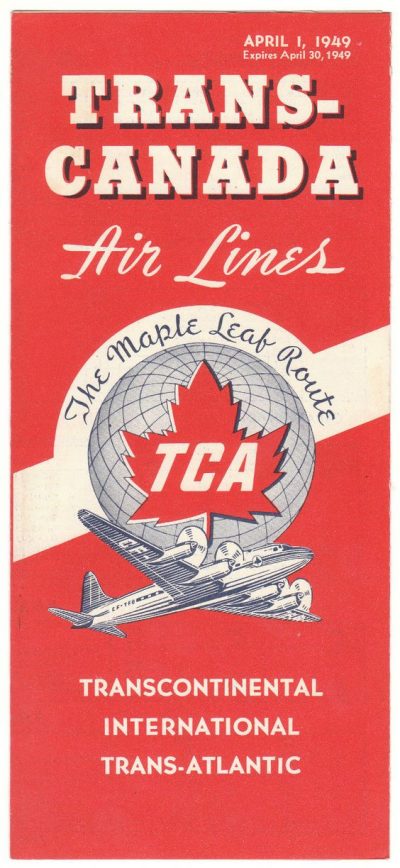

It was made of bright, shiny aluminum with rounded corners — reminiscent of the taillights on a 1958 Chevrolet. It had a clear plastic handle and the remains of two Trans-Canada Air Lines decals stuck to its sides.

Its contents were no less curious. It was chock-a-block with a chaotic jumble of personal papers including newspaper clippings, photographs, correspondence, official documents, travel brochures, an appointment book for 1949, menus from formal dinners, recital programs, and a vast array of miscellaneous ephemera as well as a sealed envelope containing what appeared to be a lock of hair.

Its contents were no less curious. It was chock-a-block with a chaotic jumble of personal papers including newspaper clippings, photographs, correspondence, official documents, travel brochures, an appointment book for 1949, menus from formal dinners, recital programs, and a vast array of miscellaneous ephemera as well as a sealed envelope containing what appeared to be a lock of hair.

The twentieth century came to a close and the suitcase remained unexamined.

Finally, ten or so years into the new millennia, I took the time to look more closely. I sorted through the astonishing and chaotic collection of paper including birth, marriage, and death documents from the 1880s — records of “hatches, matches, and despatches,” as Anglican priests liked to say — as well as hundreds of photographs of unnamed people of all ages from the early twentieth century to the 1950s.

Finally, ten or so years into the new millennia, I took the time to look more closely. I sorted through the astonishing and chaotic collection of paper including birth, marriage, and death documents from the 1880s — records of “hatches, matches, and despatches,” as Anglican priests liked to say — as well as hundreds of photographs of unnamed people of all ages from the early twentieth century to the 1950s.

Some newspaper clippings were simply fragments in which the name “Annie Watson” appeared repeatedly.

It was a time capsule from a different, mysterious, and unknown world that I invite you to explore with me.

*

It’s shortly before lunchtime, Wednesday, July 13, 1949. We are in Grimsby, Lincolnshire — England’s hard-working North Sea fishing port before Borat immortalized it — and yes, the tall dapper fellow with the light coloured tie, the one being instructed by the shorter fellow in dark-rimmed glasses, is Philip, the Duke of Edinburgh. He has recently celebrated his twenty-eighth birthday.

It will be another three years before his wife is crowned Elizabeth the Second, by the Grace of God of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland and of Her other Realms and Territories Queen, Head of the Commonwealth, Defender of the Faith. At that time, Phillip will officially become the Queen’s Consort.

At the moment, however, he is in a new, freshly painted warehouse on the Fish Docks of Grimsby where an unknown photographer employed by Fearnley Photos of Wintringham Road has captured him in company with other well-dressed folks, all of whom appear to have celebrated their twenty-eighth birthdays decades earlier.

They seem to be whispering, or perhaps murmuring, amongst themselves somewhat uneasily while keeping a safe distance from an unidentifiable, but vaguely organic and fishy, mound in the foreground, undoubtedly a frozen product of the Grimsby’s North Sea fishery.

The two chaps on the extreme left — one of whom is most likely Colonel Oliver Sutton-Nelthorpe, Deputy Lord-Lieutenant of Lincolnshire — look quite unsettled, perhaps even squeamish, by what they see; but Philip, close to the mound, remains suitably composed and politely interested.

At the left is “The Worshipful The Mayor of Grimsby, Margaret Larmour,” wearing a ribboned hat and the chains of office and pointing to the peculiar mound on the warehouse floor.

Another woman, also in a ribboned hat, and with a prominent light-coloured handbag, stands closest to the Duke while her gaze follows the extended forefinger of the mayor.

*

This intriguing photograph was among the contents of that aluminum suitcase: a lifetime’s ephemera, a jumbled and disorderly archive, and a basement guest who refused to leave.

From the contents it became clear that it had belonged to the indefatigable Annie Watson, who came to Canada from England in 1910 and lived much of her life in Vancouver before moving to Brentwood Bay on Vancouver Island before her death in the 1960s.

Born on June 4, 1883 in Middlesbrough at the home of her parents, Sarah and Thomas Edwards, Annie grew up in the shadow of All Saints’ Anglican Church where, as an adolescent, she became a devoted member of the congregation.

The suitcase reveals that in the early years of the twentieth century her free-spirited brother Tom Edwards had emigrated to western Canada in 1905. He wrote home with enthusiasm for “this lovely country” and bragged that he had “just been taking a lesson in throwing the lariat.”

Inspired by her brother’s exuberance and example, Annie accompanied her sister Laura and Tom’s best friend, Charlie Watson to Winnipeg, where they celebrated the arrival of 1911 together and launched what turned out to be a turbulent and unsettled decade for Annie.

Five months later, she and Charlie — Charles Wingate Watson – swore adherence to “The Ordinance of God and The Laws of the Province of Manitoba” and were united in the Bonds of Holy Matrimony. After four months of marriage she gave birth to a son, another Charles Wingate Watson.

*

The suitcase offers no further particulars on these two events apart from the marriage licence and birth certificate, and we are left to wonder how Annie coped.

We also know that the needs of the two Charles Wingate Watsons prevented Annie from joining her brother Tom on a scheme to homestead somewhere in Alberta, but finally in 1912 the young Watson family was able to join Tom in Calgary.

The reunion was brief. Tom went to work on the morning of August 17 and Annie never saw him alive again: he was employed as part of the crew working on the construction of the new provincial courthouse when he fell forty feet to his death. Cause of death: a fractured skull.

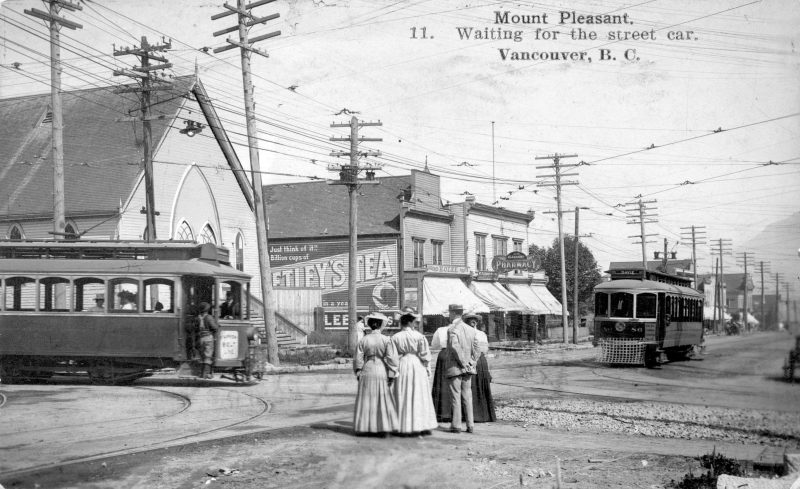

Shattered and without direction or inspiration, Annie, Charlie, and young Charles moved first to Vancouver, where they stayed long enough to establish a mailing address in Mount Pleasant and for Annie to become pregnant again; and then to Moose Jaw, where their second son, Leonard Alfred Watson, was born in November, 1913.

Charlie found work intermittently to sustain his young family until sometime in 1915, when the Watsons quit Canada and returned to Britain. The suitcase falls silent for the next six years.

Wartime and early postwar Britain, however, was not to the family’s liking, or perhaps the attractions of western Canada were greater, and by 1921 they were back in B.C. By then, their homesteading dream was far in the past and Charlie’s trade as a steelworker seemed more likely to provide for the needs of a family of four.

The Watsons returned to Mount Pleasant in Vancouver, where they had stayed briefly in 1913. It was here — in a house that, at the time of writing, is still standing — that Charlie, Annie, Charles, and Leonard settled into a brief period of stability. Charlie, the suitcase discloses, found the time and inclination to join the Masons and attend meetings at the Masonic Temple on the corner of Seymour and Georgia streets. In August, 1924 he was eligible to have the “Second Degree” conferred upon him.

Meanwhile, his work took him to a variety of industrial sites in and around the lower mainland, and occasionally he travelled to Vancouver Island for work in the shipyards or on structural renovation projects.

It was in Victoria on May 20, 1929, that an event eerily similar to the one that took place in Calgary in 1912 was repeated. When Annie answered her telephone in Mount Pleasant that evening, she learned from a co-worker that Charlie, who was working for the Dominion Bridge Company in the elevator shaft on the fifth floor of the new wing of the Empress Hotel had, at around 4 o’clock, lost his footing and “plunged 100 feet to the ground.”

According to the Daily Colonist, he died “almost instantly.” The press reported further that upon arrival by ambulance at St. Joseph’s Hospital, the attending doctor required only “a summary inspection” before he pronounced “life extinct.” Charlie’s body was then removed to the Sands Funeral Parlour where an inquest held two days later determined that the cause of death was a fractured skull.

The following day, the Steel Workers’ Union made arrangements to transfer Charlie’s remains across Georgia Strait for interment nearer his home and family, and he was laid to rest at the Masonic Cemetery on May 25, 1929.

Eighty years later Annie’s aluminum suitcase yielded an unopened envelope bearing the letterhead Mount Pleasant Undertaking Company. When held to the light, its contents are unmistakable: a lock of hair.

*

Annie and her two boys, Charles and Leonard, somehow managed to survive the lean decade of the 1930s, though quite how they did so remains a mystery. The suitcase is remarkably silent on financial matters; maybe Annie Watson’s financial suitcase was not preserved.

We do know that Annie renewed her old affiliation with the Anglican Church and joined the choir of the Oratorio Society of Vancouver. Between 1934 and 1941, she sang as one of thirty-five sopranos in numerous performances of Christian sacred music at Christ Church Cathedral in downtown Vancouver.

In the early 1940s, she moved to Kitsilano where she shared a home with her son Leonard and the family of his young bride, Stella Watson (nee Bridgman).

Stella was my mother’s eldest sister, which explains why the suitcase ended up in my family.

A receipt issued on September 28, 1944 suggests that Charlie was seldom far from her thoughts. On that date Annie purchased a gravesite adjoining his on the grassy slopes of the Vancouver Masonic Cemetery for $35. The suitcase also confirms that she enjoyed life on the grassy surfaces of the Stanley Park Lawn Bowling Club, which issued her a membership card on June 1, 1948.

*

The next significant date yielded by the hodgepodge of paper in the suitcase is July 1949, when we find Annie transported to Grimsby, England.

She had been asked by her younger sister, Margaret Larmour, to help celebrate an extraordinary personal accomplishment and a truly historic event.

Earlier in the year, Margaret had put an end to a 750 year-old tradition by being elected mayor of the Borough of Grimsby — the first woman elected since its Royal Charter was granted in 1202. Some of the excitement surrounding the momentous event seems to have worn off by July 13, when the sisters were pictured together with the Duke of Edinburgh and others in the warehouse at the Grimsby Fish Docks.

The mysterious woman standing with The Worshipful The Mayor of Grimsby, Margaret Larmour is, in fact, her sister Annie Watson from Vancouver.

Annie had been, as she liked to say, “drafted” by Margaret to serve a term as “mayoress” of Grimsby. She had crossed a continent and an ocean to share her sister’s achievement. Her chains of office can just be seen in the photograph.

For hundreds of years, the mayoress had been the wife of the mayor-elect, and Margaret’s election must have created something of a crisis for the protocol authorities in Grimsby.

In a further twist, Margaret’s husband, Matt Larmour, had finished second to his wife in the election. We don’t know if his gender ruled him ineligible for the role as mayoress or if he simply declined the honour; we suspect the first.

In any case, Grimsby’s councillors had expressed their preference for Margaret for a one-year term as mayor, and she was invited to appoint a mayoress.

She chose her sister, Annie Watson, a widow since 1929, living in far-off Vancouver.

Annie – sister, mayoress, husband-substitute, and repatriated-expat — was expected to smile pleasantly and be gracious on her sister’s behalf at social functions, official openings, awards ceremonies, and annual gatherings of various service organizations in Grimsby while Mayor Larmour attended to more important civic and administrative matters.

In fact, Annie’s role was similar to that which awaited the Duke — one that was largely social and symbolic in nature, but nonetheless much esteemed in the land of Edward Elgar’s pomp and circumstance, tradition, custom, and venerable civic rituals.

*

When the news of Annie’s appointment reached Vancouver in April 1949, a reporter from The Province dropped by her home on Cornwall Street for a chat and a photo session. He emerged with sufficient material for a series of cheery articles, beginning with, “Mrs. Anne B. Watson will lock up her little Kitsilano home next month and set sail for England and her new job as mayoress of the bustling fishing town of Grimsby.”

“At 65,” The Province continued, “the grey-haired, happy-faced little housewife is taking her new job ‘very calmly.’”

Evidently, however, the happy-faced housewife considered that Annie — the name on her birth certificate — was somewhat at odds with the dignity demanded of her new position, and she styled herself “Mrs. Anne B. Watson” for the duration of her term in Grimsby.

By July 13, when the Grimsby Fish Docks photograph was taken, Anne B. Watson was fully immersed in the role of Grimsby’s “Canadian Mayoress,” as the local press was fond of referring to her.

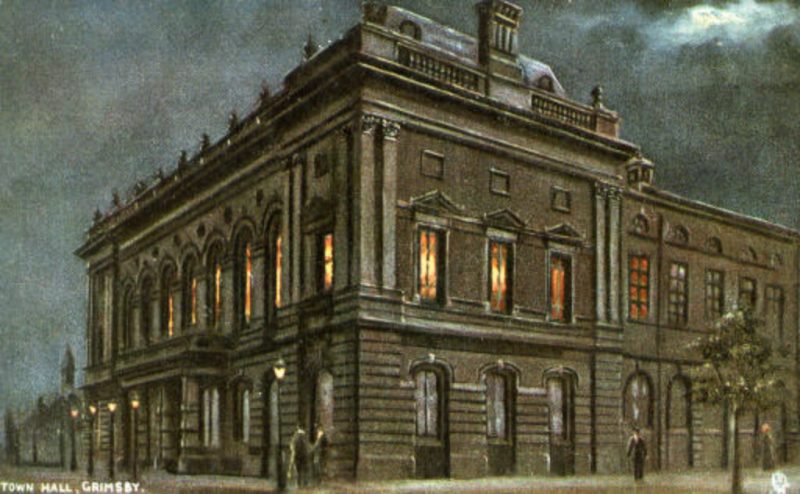

Her official installation, involving a grand procession, flowing robes, and chains of office at the Town Hall, had been preceded by what the Vancouver press described as a “spectacular parade.”

She had, as the saying goes, her work cut out for her. In May and June 1949, her new job had kept her busy.

She had hosted her inaugural “At Home” social event in Grimsby’s Town Hall for the mayors and mayoresses of surrounding Lincolnshire towns.

She had officially opened a Missionary Garden Fête, where she appeared comfortable addressing a crowd of more than 200.

She had greeted a Dutch Salvation Army Band at the Citadel in Duncombe Street.

She had attended an event organized by the Grimsby branch of the Old Age Pensioners at the Town Hall where, the Grimsby News reported, she presented “Canadian dog meat to pensioners.” (Sadly the suitcase offers no further comment on this event and we are left to ponder why Canadian dog meat would be presented to pensioners.)

She had addressed The Young Housewives Club at St. Columbia’s Church Hall.

She had attended the “At Home” social event for the new Mayoress of Cleethorpe at the Council House.

She had attended an annual “rally of the Women’s Fellowship” at the Flottergate Methodist Church and the opening and dedication of the Rotherham Memorial Medical Library at Grimsby General Hospital.

She had been present for the well-attended luncheon in honour of the Deputy Chief Scout, General Sir Frank Messervy, and took her place at the head table between the Earl of Yarborough and Councillor W.B. Bailey.

The clippings in Annie’s suitcase reveal that following the luncheon she listened as General Messervy, Commander-in-Chief of the Pakistan Army from 1947 to 1948, addressed the guests with a despairing — and eternal – plea about contemporary youth:

There is a ‘couldn’t care less’ feeling among our youth to-day — a dreadful feeling which we must get out of them. Since the end of the war, juvenile delinquency has been going up again, and we have got to take steps to stop it, for the sake of our country and for the sake of the world. We have got to put our boys and girls on the right way of life.

Following the address, more than 4,000 Scouts and Guides from all over North Lincolnshire demonstrated their commitment to “the right way of life” by marching past and saluting General Messervy and the Mayor and Mayoress of Grimsby.

By all accounts, Mrs. Anne B. Watson, Mayoress of Grimsby and resident of Kitsilano, had handled her assignments amongst the tea, cakes, fêtes, and garden parties with aplomb and a demeanour appropriate to her office, and the events of May and June proved indispensable in her preparation for hosting Philip on one of his earliest Royal Tours — the one we glimpse in progress at the Fish Docks on 13 July 1949.

At the end of her duties, the Mayoress, once again plain Annie Watson, returned to Vancouver on Trans-Canada Air Lines.

Fast forward two years to June, 1951. Annie, back at her home on York Street in Vancouver, opened a letter from her son, Charles Wingate Watson.

Chuck, as he was known to friends — though he remained Charles to his mother — now a few months short of his fortieth birthday, was an executive in the oil industry in Alberta. He had just formed his own drilling company.

On the letterhead of a Calgary hotel, one that was proud of its 200 modern fireproof rooms, he informed his mother that he would start drilling in three weeks. “My deal is over the top and looks very good,” he added.

That was the last she heard from him.

On June 26, 1951, the phone rang. It was an unfamiliar voice calling from the hospital in Princeton, B.C., at the eastern end of the new Hope-Princeton Highway.

The voice informed her that late on Saturday night, a car driven by Charles Wingate Watson had plunged off the highway near the small mining community of Hedley.

Charles, who suffered a fractured skull and several other broken bones, had died three hours later at the Princeton Hospital.

In a small, perforated notepad that she kept near the telephone, Annie wrote:

Doctors report

Extensive brain injury

Skull fractured

interval between cause & death 3 hours

fractured left humerus

accident

Auto accident nr. Hedley, B.C.

June 25, 1951

Annie knew those words “skull fracture” and “accident” well. They were the same words used in 1912 when her brother Tom plunged to his death at a construction site in Calgary.

They were the same words used in 1929 to describe the death of her husband, Charles Wingate Watson, at the bottom of an Empress Hotel elevator shaft.

“Company Executive Killed,” proclaimed the Vancouver Province and the Vancouver Sun. They reported that Charles was driving from Vancouver to Penticton to meet with men “on oil matters” when the wheels of his car skidded off the paved surface onto a soft shoulder before plunging into a tree.

Sometime afterward, Annie Watson consigned the documents and clippings of this latest tragedy to the aluminum suitcase.

What she did with her grief and sorrow we can only try to imagine.

*

Having lived almost as long as her husband and son combined, in May of 1966 Annie Watson, aged 83, joined them under the grassy slopes of the Vancouver Masonic Cemetery.

She was survived by her younger son, Leonard, and his wife Stella. A partner in Bridgman’s Studios (portrait photographers) in Vancouver, Leonard eventually settled near Brentwood Bay where he farmed until his death in 1978.

His mother’s suitcase, detached from his estate and sundered from the actors and tragedies it contained, passed to my branch of the family and survived to form the basis of this story.

*

Graham Brazier lives on Denman Island, where he gardens, writes, and ponders British Columbia history. With Nick Doe, he edited Proceedings of the Islands of British Columbia Conference 2004 (Arts Denman: 2005), and has published articles in Canada’s History (formerly The Beaver), British Columbia History, and other publications. He is the editor of The Fort Victoria Journal: http://www.fortvictoriajournal.ca/about.php<http://www.fortvictoriajournal.ca/about.php>

*

The Ormsby Review. More Readers. More Reviews. More Often.

Reviews Editor: Richard Mackie

Reviews Publisher: Alan Twigg

The Ormsby Review is hosted by Simon Fraser University. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Cole Harris, Wade Davis, Hugh Johnston, Patricia Roy, David Stouck, and Graeme Wynn.

The Ormsby Review is hosted by Simon Fraser University.

—

BC BookWorld

ABCBookWorld

BCBookLook

BC BookAwards

The Literary Map of B.C.

The Ormsby Review

Leave a Reply