Wade Davis wins Ryga Award

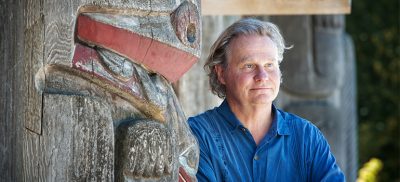

Few, if any, British Columbians have seen as much of the diversity of the world's populations as Wade Davis.

May 11th, 2017

Wade Davis addresses a TED conference; he'll speak at Vancouver Public Library on June 29.

Now the UBC-based anthropologist has won the George Ryga Award for Social Awareness.

If there is anyone from B.C. who has a broad and abiding knowledge of societies on this planet, it’s gotta be the much-travelled Wade Davis who was National Geographic Explorer-in-Residence from 2000 to 2013.

Therefore it’s no surprise that Wade Davis: Photographs (D&M), the latest book from this acclaimed explorer, ethnographer, botanist, writer, documentary photographer/cinematographer — and now UBC professor of anthropology — has won the George Ryga Award for Social Awareness.

This B.C.-published book has since been picked up by National Geographic for re-publication worldwide.

Runners-up this year were Stephen Collis for My Blockadia (Talonbooks) and Eric Jamieson for The Native Voice: The Story of How Maisie Hurley and Canada’s First Aboriginal Newspaper Changed a Nation (Caitlin).

Davis has made seventeen films and written many books. His five main stage TED Talks have been viewed by three million people. His coffee table compendium Wade Davis: Photographs affords a tiny yet diverse glimpse into the thousands of images he created while visiting diverse cultures. Text and context is provided for the 140 photos selected for the book. He writes:

My goal was not to document the exotic other, but rather to identify stories that had deep metaphorical resonance, something universal to tell us about the nature of being alive…. Our mandate fundamentally was to provide a platform for indigenous voices, even as our lens revealed inner horizons of thought, spirit and adaption that might inspire, in the words of Father Thomas Berry, entirely new dreams of the earth.

For Wade Davis: Photographs, Davis selected favourite photographs from the thousands he has taken during his forty-year career. These intimate portraits of family and community life are universal in tone, and yet represent countless geographical and cultural spaces, telling the story of the human condition across the globe.

His photographs have appeared in many publications such as National Geographic, Time, Geo, People, Men’s Journal and Outside.

At the time of publication he is the BC Leadership Chair in Cultures and Ecosystems at Risk at the University of British Columbia, a member of the National Geographic Society Explorers Council and Honorary Vice-President of the Royal Canadian Geographical Society.

Davis will receive the $2,500 Ryga Award at the Vancouver Public Library on June 29 at 7 p..m. It’s a free public event at which historian Rolf Knight will also accept the George Ryga Lifetime Achievement Award.

Judges for the Ryga Award were VPL librarian Jane Curry, freelance editor/writer Beverly Cramp and author/professor Trevor Carolan.

*

Along with B.C. photographer Ted Grant and B.C.-born filmmaker Atom Egoyan, Wade Davis was appointed to the Order of Canada in December of 2015 as an author, explorer, ethnobotanist and photographer.

The citation read, “Wade Davis is recognized for his work to promote conservation of the natural world. A Harvard-educated anthropologist and explorer-in-residence at the National Geographic Society, Davis has written 15 books including The Serpent and the Rainbow. Wade Davis is a professor of anthropology and the B.C. Leadership Chair in Cultures and Ecosystems at Risk at the University of B.C.”

Born in West Vancouver, B.C. in 1953, Wade Davis is a widely travelled Harvard ethnobotanist, anthropologist and biologist who grew up in Quebec and attended Brentwood College in Mill Bay on Vancouver Island. “I was a product of the Sixties,” he says. “I had a strong sense of adventure and wanted to experience the world.” Between 1999 and 2013 he served as Explorer-in-Residence at the National Geographic Society.

His books have included The Serpent and the Rainbow, One River, The Wayfinders and The Sacred Headwaters. He holds degrees in anthropology and biology and received his Ph.D. in ethnobotany, all from Harvard University. His many film credits included Light at the Edge of the World, an eight-hour documentary series written and produced for the National Geographic.

By 2015, Davis had received eleven honourary degrees, as well as the 2009 Gold Medal from the Royal Canadian Geographical Society for his contributions to anthropology and conservation, the 2011 Explorers Medal, the highest award of the Explorers Club, the 2012 David Fairchild Medal for botanical exploration, and the 2013 Ness Medal for geography education from the Royal Geographical Society.

Into the Silence received the 2012 Samuel Johnson prize, arguably the top award for literary non-fiction in the English language.

His Penan: Voice of the Borneo Rainforest, co-written with Thom Henley, details the plight of the Penan people in Sarawak. An assignment in Haiti led to his writing The Serpent and the Rainbow, which became a Hollywood movie.

Wade Davis’s The Sacred Headwaters: The Fight to Save the Stikine, Skeena, and Nass is described as a visual feast and plea to save an extraordinary region in North America for future generations.

In The Sacred Headwaters, Wade Davis, describes the region’s beauty, the threats to it, and the response of native groups and other inhabitants, complemented by the voices of the Tahltan elders.

Davis has conducted ethnographic fieldwork among several indigenous societies of northern Canada. He is an Honorary Research Associate of the Institute of Economic Botany of the New York Botanical Garden, a Collaborator in botany at the Smithsonian Institution, a fellow of both the Linnean Society and the Explorer’s Club, and has been Executive Director of the Endangered People’s Project.

Review of the author’s work by BC Studies:

The Sacred Headwaters: The Fight to Save the Stikine, Skeena and Nass

BOOKS:

The Serpent and the Rainbow: A Harvard Scientist’s Astonishing Journey Into the Secret Societies of Haitain Voodoo, Zombies and Magic (Simon & Schuster, 1986)

Passage of Darkness: The Ethnobiology of the Haitian Zombia (Chapel Hill, 1988)

Penan: Voice for the Borneo Rain Forest, with Thom Henley (Western Canada Wilderness Committe, 1990)

Nomads of the Dawn: The Penan of the Borneo Rainforest, with Ian Mackenzie and Shane Kennedy (Pomegranate, 1995)

One River: Explorations and Discoveries in the Amazon Rain Forest (Touchstone, 1996)

Shadows in the Sun: Travels to Landscapes of Spirits and Desire (Pomegranate Art Books, 1998)

Rainforest: Ancient Realm of the Pacific Northwest, text by Wade Davis, photographs by Graham Osborne(Greystone, 1998)

The Clouded Leopard: Travels to Landscapes of Spirits and Desire (D&M, 1999)

Light at the Edge of the World: A Journey through the Realm of Vanishing Cultures (D&M, 2001, 2007).

The Lost Amazon: The Photographic Journey of Richard Evans Schultes (D&M, 2004)

The Wayfinders: Why Ancient Wisdom Matters in the Modern World (Anansi, 2009)

Into the Silence: The Great War, Mallory, and the Conquest of Everest (Knopf Canada 2011) 978-0-676-97919-0 $32.95

The Sacred Headwaters: The Fight to Save the Stikine, Skeena, and Nass (Greystone Books/David Suzuki Foundation 2011; republished paperback Greystone, 2015) 9781553658801

River Notes: A Natural History of the Colorado (Island Press 2012). $22.95

Into the Silence (2012)

Wade Davis: Photographs (D&M 2016) $39.95 978-1-77162-124-3

*

Wade Davis: Photographs

by Wade Davis

Madeira Park: Douglas & McIntyre, 2016. $39.95 / 978-1-77162-124-3

Reviewed by David Mattison

To say that Wade Davis has had an extraordinary, brilliant, and in the end very lucky career would be a great understatement.

To say that Wade Davis has had an extraordinary, brilliant, and in the end very lucky career would be a great understatement.

Originally from West Vancouver, he returned to his British Columbian roots in 2013, according to a UBC media release, when he “joined the University of British Columbia to advance global awareness of cultures and ecosystems at risk:” (http://news.ubc.ca/2013/12/18/wade-davis-acclaimed-anthropologist-and-author-joins-the-university-of-british-columbia/).

His studies and travels started at the age of fourteen when, as a student at Brentwood College on Vancouver Island, he went on an exchange to Colombia. Since then, he has been to some of the remotest locations in which humanity has taken root. “Many anthropologists of my generation entered the field with a similar hunger for raw and authentic experience,” he notes (p. 10).

His photographs attest to the wide variety of cultural experiences to which he opened himself, and he writes with passion and authority about the places, peoples, and cultural practices he’s encountered. (Some of his descriptions of initiation rites, especially in New Guinea, are not for the faint of heart.)

He provides some haunting and poignant images. The two that struck me the most were the title page of a Dogon man casting his eyes over the land of a religious enemy, and the cover portrait of a Colombian Amazon boy.

In his introduction, Davis provides a mini-history of anthropology, highlighting the work of the brilliant German-American anthropologist Franz Boas (1858-1942), who worked among coastal B.C. First Nations communities and directed the Jesup North Pacific Expedition of 1897 (for its photographic records see the American Museum of Natural History at https://anthro.amnh.org/jesup_photos). I found it unusual that someone as knowledgeable as Davis does not, at least in this book, mention the close connection and utility of photography to these pioneering anthropologists. Boas was himself a photographer and hired commercial photographers to assist him. One of his most important Kwakwaka’wakw informants, the half-English and half-Tlingit George Hunt, was also an amateur photographer.

Davis’s intent during his time as NGS Explorer-in-Residence, as he shares in his introduction, was to “take the global audience of the NGS … to points in the ethnosphere where the beliefs, practices and intuitions are so dazzling that one cannot help but come away with a new appreciation for the wonder of the human imagination made manifest in culture.”

To this end, he shares with us religious ceremonies from West Africa and Nepal, and festivals of life, food and the spirit from places, many of them sacred in nature, as disparate as the Peruvian Andes, the Tobriand Islands, and Australia.

Wade Davis: Photographs also serves as a useful primer on the significance of cultural anthropology and Davis provides an evocative summary (p. 20) of his primary mission during his Explorer-in-Residence years.

A Dogon elder from the cliffs of the Bandiagara escarpment in Mali peers towards the lands of the Fulami, one of the many Muslim tribes that have threatened the cultural survival of his people for a thousand years.

For example, he discusses the crucial link between language and culture and assesses linguist Noam Chomsky’s influence. Chomsky was – unfairly — blamed for language loss by suggesting that there is a deep universal grammar for all human languages; that babies and toddlers possess an innate software for language acquisition; and that therefore there is no need to record the mere superstructure and variety of languages that face extinction.

As Canada’s Indigenous communities will attest, this twisted logic helped erase what Davis — reporting his conversation with MIT linguist Ken Hale — calls the “flash of the human spirit, the means by which the soul of a culture comes into the material world. Every language is an old-growth forest of the mind, a watershed of thought, an ecosystem of social and spiritual possibilities” (p. 14).

Oddly, Davis makes no reference to any efforts to stave off language loss such as the Long Now Foundation’s Rosetta Project (http://rosettaproject.org/) and British Columbia-based FirstVoices (http://www.firstvoices.com) for the preservation and revitalization of Canada’s First Nations languages.

Indeed, Davis’s only reference to any organization other than the NGS involved in advocacy for Indigenous peoples is Cultural Survival (https://www.culturalsurvival.org/), founded in 1972 by Harvard University professor David Maybury-Lewis (1929-2007) and his wife Pia.

I must speak now as a historian of the techniques and artistry of photography. While Davis writes eloquently about those who influenced him directly as a photographer, or who informed his work through their theoretical or philosophical insights into photography, he is a little shy on some technical aspects of his photographic work.

One of the issues around publishing photographs is how much detail to provide. Very few photographs are self-documenting. They require, indeed demand, an explanation or answers to the usual questions of who, what, where, why and how. I feel that Davis has let his readers down by not providing answers to some of those questions. I was mildly curious about his photographic technique (camera model, lens, shutter speed, etc.). None of that information is available here.

Young women gather at sunset on Marsabit Mountain in Kenya, awaiting warriors who will sing and dance for them long into the night.

He states in his introduction (p. 24) that “Many of the photographs … were taken as we made these films [he made seventeen films while NGS Explorer-in-Residence]; others came out of other expeditions or the journeys I went on as a lecturer for the travel office at the NGS….”

While all the photographs are in colour, most are not dated. All we know is that they were taken between 2000 and 2013. The photographs are grouped together by continent, region, or country, and Davis provides location-specific information for all the images in their respective chapter.

His goal as a photographer, Davis writes movingly, “is always to try to find in the chaos of visual perception and experience that perfect moment when subject, luminosity and perspective come together to affirm the eternal dignity of the human spirit.”

Given the difficult, if almost non-existent lighting conditions under which some of the photographs were taken, he has for the most part succeeded. I say this because not all the photographs are of people. A few are landscape views devoid of human life, possibly meant to illustrate the sometimes extreme and difficult environmental conditions to which cultures have adapted.

While Davis calls the language loss and subsequent disappearance of knowledge “among the central challenges of our time,” he also admits, somewhat too starkly for my taste, that, “As an anthropologist fully aware of the dynamic, ever-changing nature of culture, I had no interest in preserving anything” (p. 27).

Davis leaves us to decide for ourselves how we will interact with societies and cultures so different from each other, and from our own; and Wade Davis: Photographs will stand as testament to his remarkable career and to his gifts as a writer, communicator, and teacher.

*

(http://www.wadedavis.com)

Leave a Reply